Space Command chief throws cold water on the question of UAPs in space

Judging from recent comments from Gen. Stephen Whiting, head of US Space Command, we shouldn’t expect anything like that in whatever the government might release in response to Trump’s pending order.

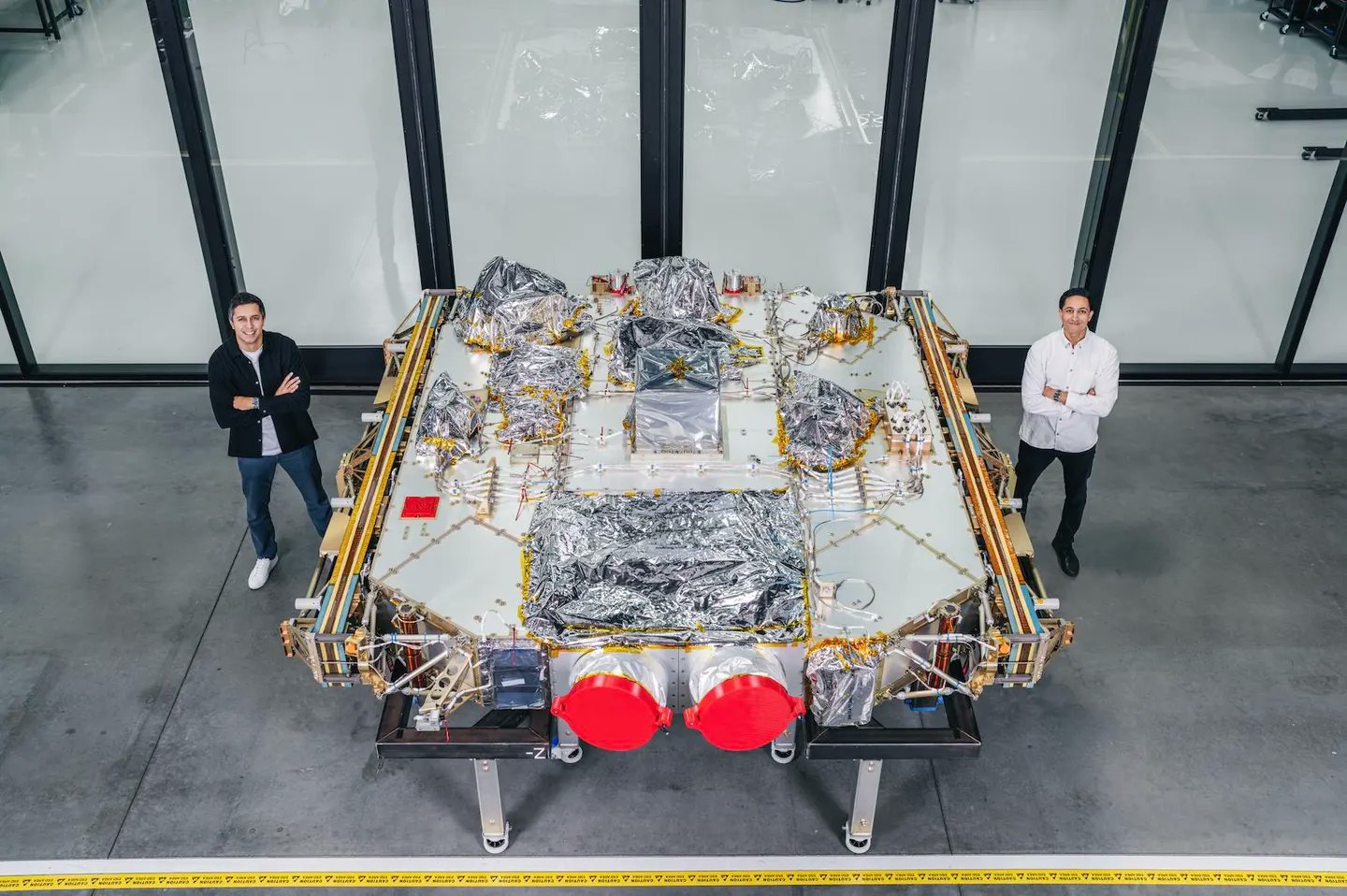

Gen. Stephen Whiting, commander of US Space Command. Credit: US Air Force/Eric Dietrich

“I can say, I, personally, was very interested in the president’s announcement,” Whiting told reporters last week at the Air and Space Forces Association’s Warfare Symposium in Colorado. “I look forward to seeing what data does come out. I can also tell you, as a space operator now of 36 years, having spent a lot of time with space domain awareness sensors, tracking things in space, I’ve never seen anything in space other than manmade objects, so I am not aware of anything that is extraterrestrial, other than comets and things like that.

“But I’m fascinated in the topic,” he continued. “And if something’s revealed, I’ll be interested as an American citizen.”

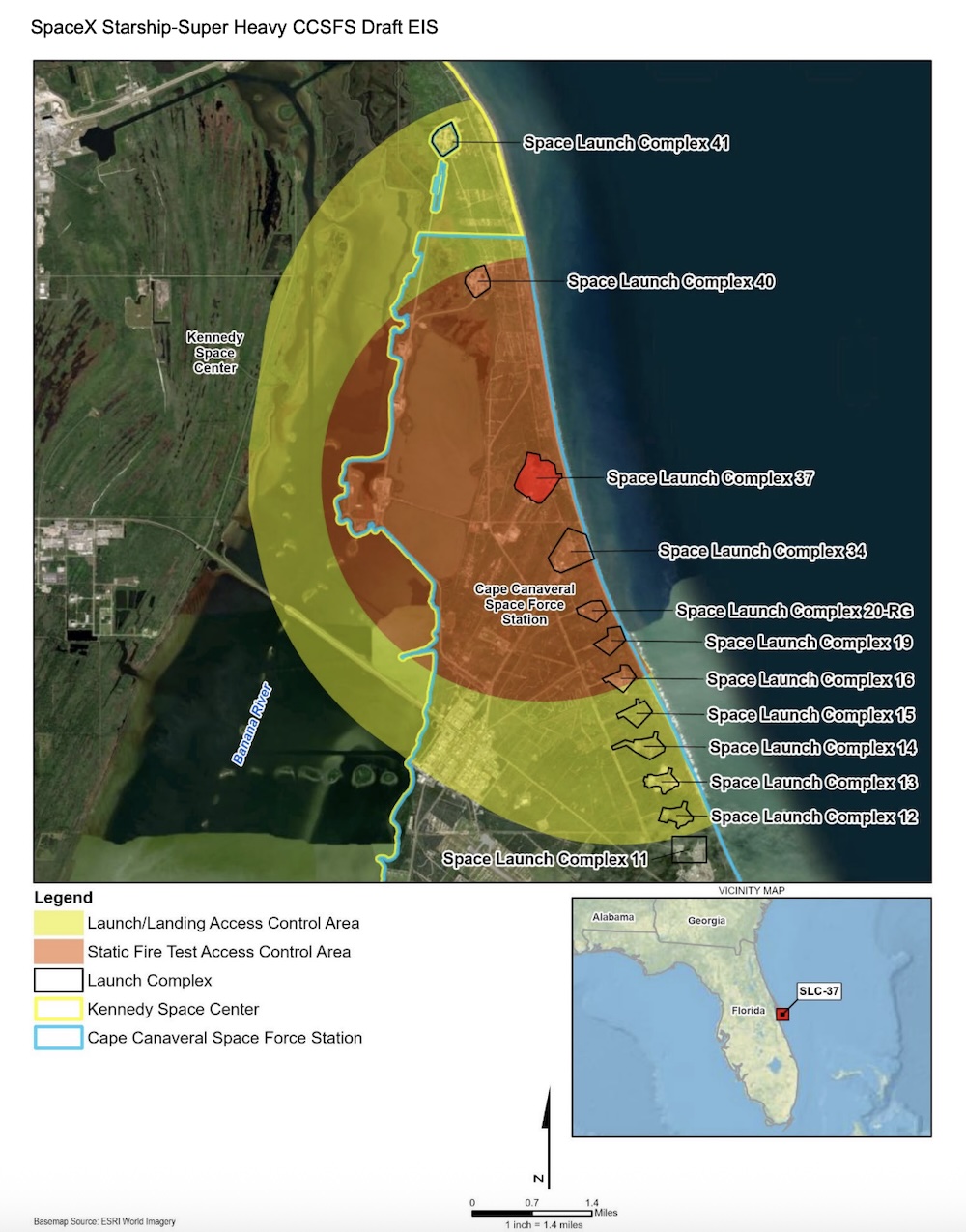

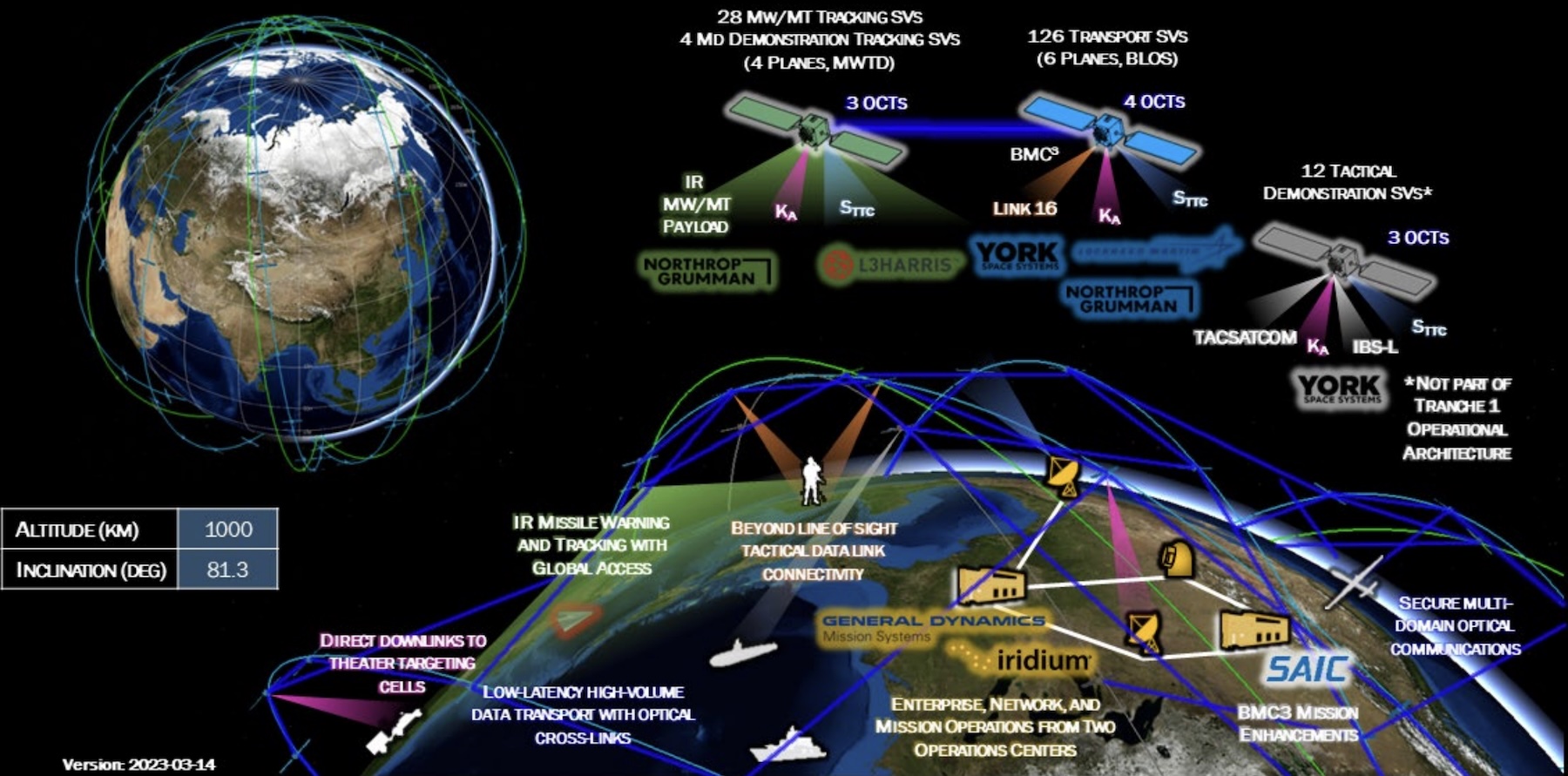

Space Command’s charge includes an area of responsibility (AOR) that extends from the top of Earth’s atmosphere to the Moon and beyond. One of its missions is to track, monitor, and catalog objects in space. Whiting suggested that everything he’s seen in orbit is attributable to a human-made or natural origin.

“We will respond to any presidential direction to go look at our files, but I think the term of art now is UAP, and the A is aerial, so these are things that are below the Kármán line (100 kilometers), that are in the atmosphere,” Whiting said. “I’ve seen some of the same videos and radar data that all of you have, and my guess is those relevant services and combatant commands will turn that data over. I’m very interested in the topic, but I have no personal experience with any of those phenomena.”

Space Command chief throws cold water on the question of UAPs in space Read More »