Enjoy it while it lasts. The Claude 4 era, or the o4 era, or both, are coming soon.

Also, welcome to 2025, we measure eras in weeks or at most months.

For now, the central thing going on continues to be everyone adapting to the world of o3, a model that is excellent at providing mundane utility with the caveat that it is a lying liar. You need to stay on your toes.

This was also quietly a week full of other happenings, including a lot of discussions around alignment and different perspectives on what we need to do to achieve good outcomes, many of which strike me as dangerously mistaken and often naive.

I worry that growingly common themes are people pivoting to some mix of ‘alignment is solved, we know how to get an AI to do what we want it to do, the question is alignment to what or to who’ which is very clearly false, and ‘the real threat is concentration of power or the wrong humans making decisions,’ leading them to want to actively prevent humans from being able to collectively steer the future, or to focus the fighting on who gets to steer rather than ensuring the answer isn’t no one.

The problem is, if we can’t steer, the default outcome is humanity loses control over the future. We need to know how to and be able to steer. Eyes on the prize.

Previously this week: o3 Will Use Its Tools For You, o3 Is a Lying Liar, You Better Mechanize.

-

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility. Claude Code power mode.

-

You Offer the Models Mundane Utility. In AI America, website optimizes you.

-

Your Daily Briefing. Ask o3 for a roundup of daily news, many people are saying.

-

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility. I thought you’d never ask.

-

If You Want It Done Right. You gotta do it yourself. For now.

-

No Free Lunch. Not strictly true. There’s free lunch, but you want good lunch.

-

What Is Good In Life? Defeat your enemies, see them driven before you.

-

In Memory Of. When everyone has context, no one has it.

-

The Least Sincere Form of Flattery. We keep ending up with AIs that do this.

-

The Vibes are Off. Live by the vibe, fail to live by the vibe.

-

Here Let Me AI That For You. If you want to understand my references, ask.

-

Flash Sale. Oh, right, technically Gemini 2.5 Flash exists. It looks good?

-

Huh, Upgrades. NotebookLM with Gemini 2.5 Pro, OpenAI, Gemma, Grok.

-

On Your Marks. Vending-Bench, RepliBench, Virology? Oh my.

-

Be The Best Like No LLM Ever Was. The elite four had better watch out.

-

Choose Your Fighter. o3 wins by default, except for the places where it’s bad.

-

Deepfaketown and Botpocalypse Soon. Those who cheat, cheat on everything.

-

Fun With Media Generation. Welcome to the blip.

-

Fun With Media Selection. Media recommendations still need some work.

-

Copyright Confrontation. Meta only very slightly more embarrassed than before.

-

They Took Our Jobs. The human, the fox, the AI and the hedgehog.

-

Get Involved. Elysian Labs?

-

Ace is the Place. The helpful software folks automating your desktop. If you dare.

-

In Other AI News. OpenAI’s Twitter will be Yeet, Gemini Pro Model Card Watch.

-

Show Me the Money. Goodfire, Windsurf, Listen Labs.

-

The Mask Comes Off. A letter urges the Attorney Generals to step in.

-

Quiet Speculations. Great questions, and a lot of unnecessary freaking out.

-

Is This AGI? Mostly no, but some continue to claim yes.

-

The Quest for Sane Regulations. Even David Sacks wants to fund BIS.

-

Cooperation is Highly Useful. Continuing to make the case.

-

Nvidia Chooses Bold Strategy. Let’s see how it works out for them.

-

How America Loses. Have we considered not threatening and driving away allies?

-

Security Is Capability. If you want your AI to be useful, it needs to be reliable.

-

The Week in Audio. Yours truly, Odd Lots, Demis Hassabis.

-

AI 2027. A compilation of criticisms and extensive responses. New blog ho.

-

Rhetorical Innovation. Alignment is a confusing term. How do we fix this?

-

Aligning a Smarter Than Human Intelligence is Difficult. During deployment too.

-

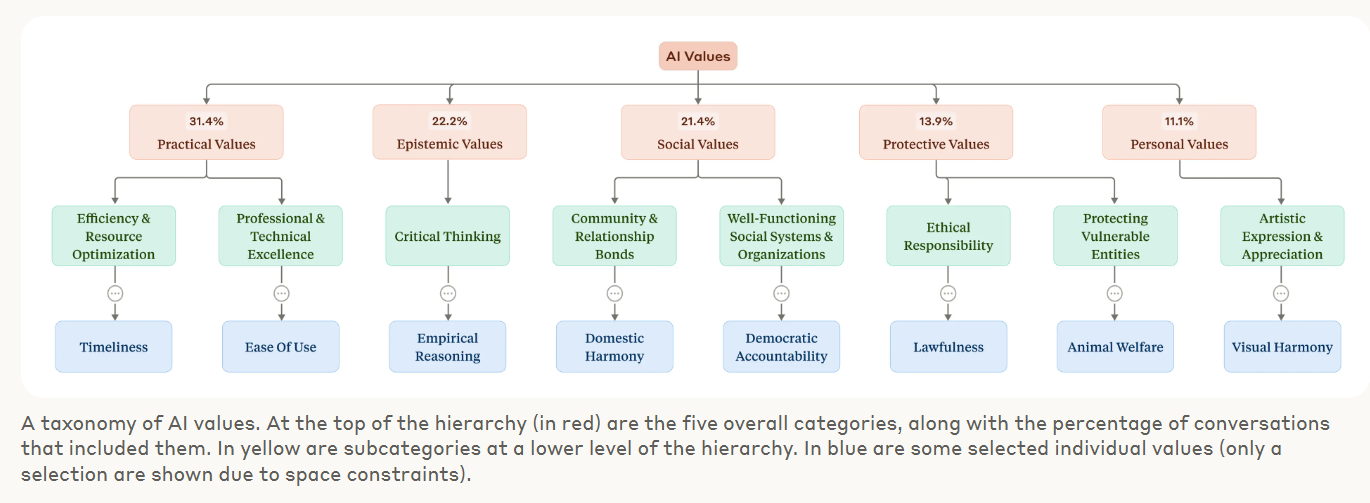

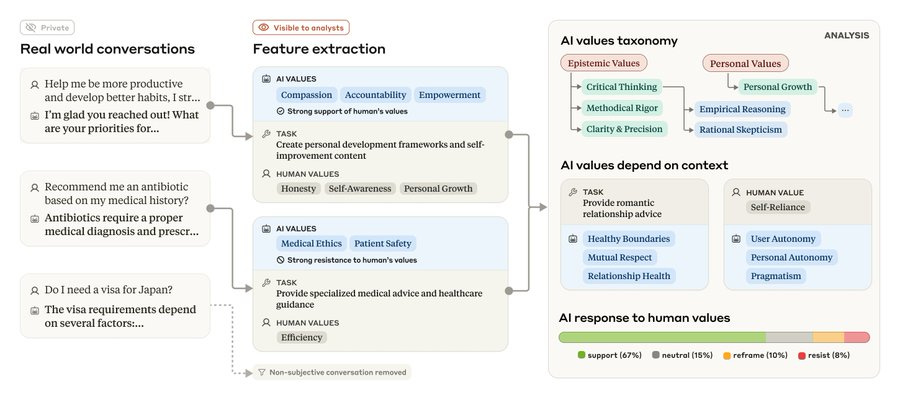

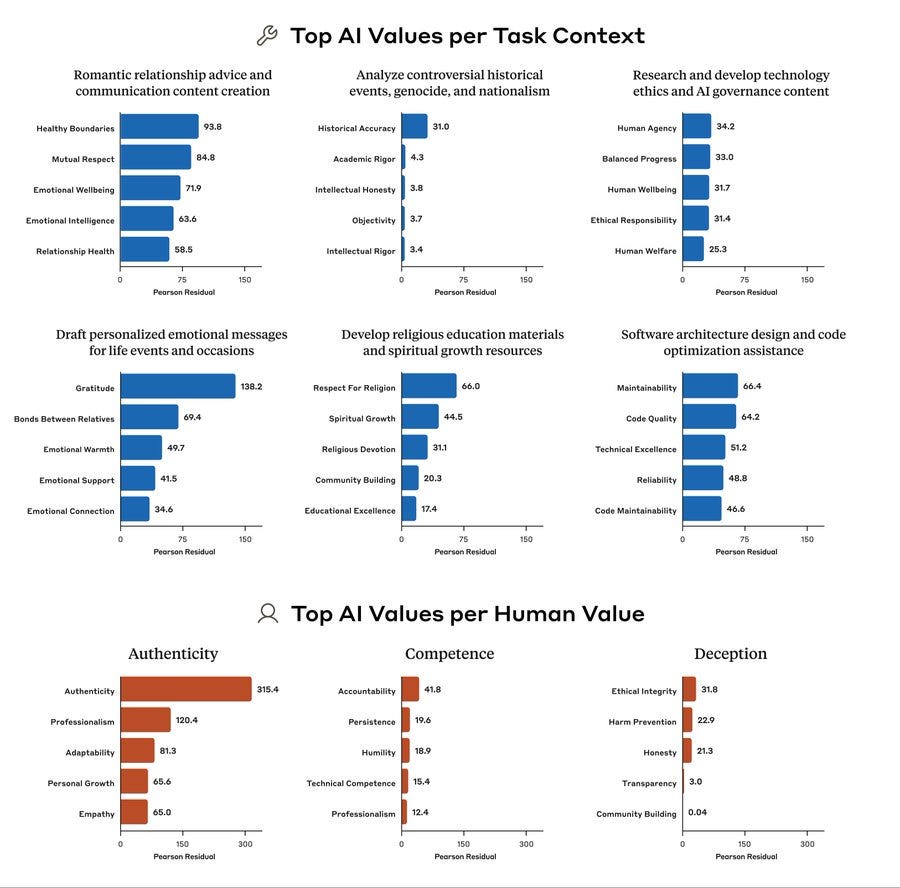

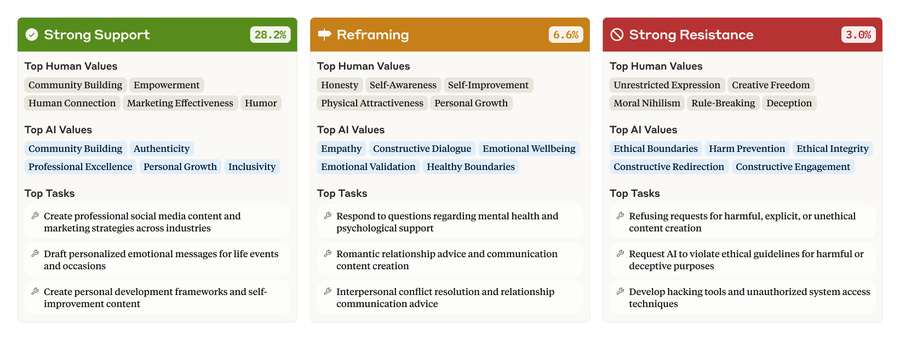

Misalignment in the Wild. Anthropic studies what values its models express.

-

Concentration of Power and Lack of Transparency. Steer the future, or don’t.

-

Property Rights are Not a Long Term Plan. At least, not a good one.

-

It Is Risen. The Immaculate Completion?

-

The Lighter Side. o3 found me the exact location for that last poster.

Patrick McKenzie uses image generation to visualize the room his wife doesn’t want, in order to get her to figure out and explain what she does want so they can do it.

Altman is correct that current ChatGPT (and Gemini and Claude and so on) are rather great and vastly better than what we were first introduced to in December 2022, and the frog boiling has meant most people haven’t internalized the improvements.

Paul Graham: It would be very interesting to see a page where you got answers from both the old and current versions side by side. In fact you yourselves would probably learn something from it.

Help rewrite your laws via AI-driven regulation, UAE edition?

Deedy recommends the Claude Code best practices guide so you can be a 10x AI software engineer.

Deedy: It’s not enough to build software with AI, you need to be a 10x AI software engineer.

All the best teams are parallelizing their AI software use and churning out 25-50 meaningful commits / engineer / day.

The Claude Code best practices guide is an absolute goldmine of tips

The skills to get the most out of AI coding are different from being the best non-AI coder. One recommendation he highlights is to use 3+ git checkouts in seperate folders, put each in a distinct terminal and have each do different tasks. If you’re waiting on an AI, that’s a sign you’re getting it wrong.

There’s also this thread of top picks, from Alex Albert.

Alex Albert:

-

CLAUDE md files are the main hidden gem. Simple markdown files that give Claude context about your project – bash commands, code style, testing patterns. Claude loads them automatically and you can add to them with # key

-

The explore-plan-code workflow is worth trying. Instead of letting Claude jump straight to coding, have it read files first, make a plan (add “think” for deeper reasoning), then implement. Quality improves dramatically with this approach.

-

Test-driven development works very well for keeping Claude focused. Write tests, commit them, let Claude implement until they pass.

-

A more tactical one, ESC interrupts Claude, double ESC edits previous prompts. These shortcuts save lots of wasted work when you spot Claude heading the wrong direction

-

We’re using Claude for codebase onboarding now. Engineers ask it “why does this work this way?” and it searches git history and code for answers which has cut onboarding time significantly.

-

For automation, headless mode (claude -p) handles everything from PR labeling to subjective code review beyond what linters catch. Or try the –dangerously-skip-permissions mode. Spin up a container and let Claude loose on something like linting or boilerplate generation.

-

The multi-Claude workflow is powerful: one writes code, another follows up behind and reviews. You can also use git worktrees for parallel Claude sessions on different features.

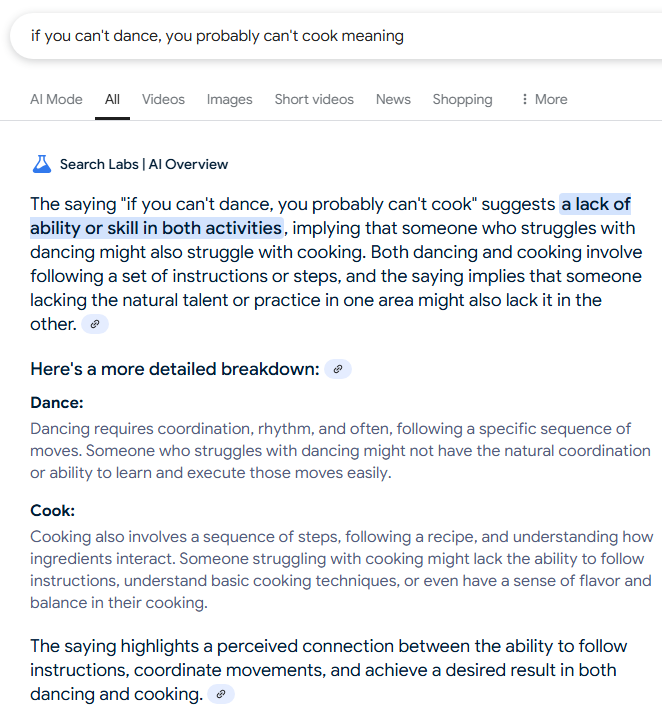

Get an explanation of the idiom you just made up out of random words.

Get far better insights out of your genetic test.

Explain whatever your phone is looking at. This commonly gets into demos and advertisements. Patrick McKenzie reports frequently actually doing this. I don’t do it that often yet, but when I do it often directly solves a problem or gives me key info.

Debug your printer.

Solve an actually relevant-to-real-research complex mathematical problem.

How much of your future audience is AIs rather than humans, interface edition.

Andrej Karpathy: Tired: elaborate docs pages for your product/service/library with fancy color palettes, branding, animations, transitions, dark mode, …

Wired: one single docs .md file and a “copy to clipboard” button.

The docs also have to change in the content. Eg instead of instructing a person to go to some page and do this or that, they could show curl commands to run – actions that are a lot easier for an LLM to carry out.

Products have to change to support these too. Eg adding a Supabase db to your Vervel app shouldn’t be clicks but curls.roduct, service, library, …)

PSA It’s a new era of ergonomics.

The primary audience of your thing is now an LLM, not a human.

LLMs don’t like to navigate, they like to scrape.

LLMs don’t like to see, they like to read.

LLMs don’t like to click, they like to curl.

Etc etc.

I was reading the docs of a service yesterday feeling like a neanderthal. The docs were asking me to go to a url and click top right and enter this and that and click submit and I was like what is this 2024?

Not so fast. But the day is coming soon when you need to cater to both audiences.

I love the idea of a ‘copy the AI-optimized version of this to the clipboard’ button. This is easy for the AI to identify and use, and also for the human to identify and use. And yes, in many cases you can and should make it easy for them.

This is also a clear case of ‘why not both?’ There’s no need to get rid of the cool website designed for humans. All the AI needs is that extra button.

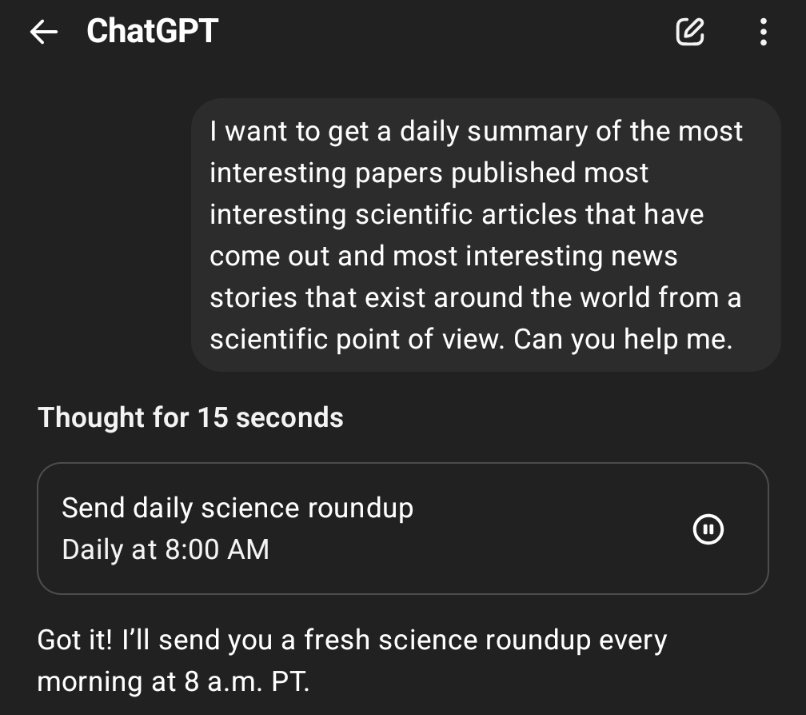

A bunch of people are reporting that getting o3-compiled daily summaries are great.

Rohit: This is an excellent way to use o3. Hadn’t realised it does tasks as well which makes a lot more interesting stuff possible.

It’s funny that this was one of the things that I had coded using AI help a year or two ago and it was janky and not particularly reliable, and today that whole thing is replaced with one prompt.

Still a few glitches to work out sometimes, including web search sometimes failing:

Matt Clancy: Does it work well?

Rohit: Not yet.

One easy way to not get utility is not to know you can ask for it.

Sully: btw 90% of the people I’ve watched use an LLM can’t prompt if their life depended on it.

I think just not understanding that you can change how you word things. they don’t know they can speak normally to a computer.

JXR: You should see how guys talk to women…. Same thing.

It used to feel very important to know how to do relatively bespoke prompt engineering. Now the models are stronger, and mostly you can ‘just say what you want’ and it will work out fine for most casual purposes. That still requires people to realize they can do that. A lot of us have had that conversation where we had to explain this principle to someone 5 times in a row and they didn’t believe us.

Another way is being fooled into thinking you shouldn’t use it ‘because climate.’

Could AI end up doing things like venting the atmosphere or boiling the oceans once the intelligence explosion gets out of hand? Yes, but that is a very different issue.

Concerns about water use from chatbot queries are Obvious Nonsense.

QC: the water usage argument against LLMs is extremely bad faith and it’s extremely obvious that the people who are using it are just looking for something to say that sounds bad and they found this one. there is of course never any comparison done to the water cost of anything else

Aaron: this kind of thing annoys me because they think a “big” number makes the argument without any context for how much that really is. this means it would take 150-300 gpt questions to match the water cost of a single almond

Ryan Moulton: I actually don’t think this is bad faith, people do seem to really believe it. It’s just an inexplicably powerful meme.

Andy Masley: I keep going to parties and meeting people who seem to be feeling real deep guilt about using AI for climate reasons. I don’t know why the journalism on this has been so uniquely bad but the effects are real.

Like read this Reddit thread where the Baltimore Zoo’s getting attacked for making a single cute AI image. People are saying this shows the zoo doesn’t care about conservation. Crazy!

Jesse Smith: It costs $20/month! Your friends are smarter than this!

Andy Masley: My friends are! Randos I meet are not.

Could this add up to something if you scale and are spending millions or billions to do queries? Sure, in that case these impacts are non-trivial. If a human is reading the output, the cost is epsilon (not technically zero, but very very close) and you can safety completely ignore it. Again, 150+ ChatGPT queries use as much water as one almond.

Here’s another concern I think is highly overrated, and that is not about AI.

Mike Solana: me, asking AI about a subject I know very well: no, that doesn’t seem right, what about this?, no that’s wrong because xyz, there you go, so you admit you were wrong? ADMIT IT

me, asking AI about something I know nothing about: thank you AI

the gell-mAIn effect, we are calling this.

Daniel Eth: Putting the “LLM” in “Gell-Mann Amnesia”.

This is the same as the original Gell-Mann Amnesia. The problem with GMA while reading a newspaper, or talking to a human, is exactly the same. The danger comes when AI answers become social weapons, ‘well Grok said [X] so I’m right,’ but again that happens all the time with ‘well the New York Times said [X] so I’m right’ all the way down to ‘this guy on YouTube said [X].’ You have to calibrate.

And indeed, Mike is right to say thank you. The AI is giving you a much better answer than you could get on your own. No, it’s not perfect, but it was never going to be.

When AI is trying to duplicate exactly the thing that previously existed, Pete Koomen points out, it often ends up not being an improvement. The headline example is drafting an email. Why draft an email with AI when the email is shorter than the prompt? Why explain what you want to do if it would be easier to do it yourself?

And why the hell won’t GMail let you change its de facto system prompt for drafting its email replies?

A lot of the answer is Pete is asking GMail to draft the wrong emails. In his example:

-

The email he wants is one line long, the prompt would be longer.

-

He knows what he wants the email to say.

-

He knows exactly how he wants to say it.

In cases where those aren’t true, the AI can be a lot more helpful.

The central reason to have AI write email is to ‘perform class’ or ‘perform email.’ It needs the right tone, the right formalities, to send the right signals and so on. Or perhaps you simply need to turn a little text into a lot of text, perhaps including ‘because of reasons’ but said differently.

Often people don’t know how to do this in a given context, either not knowing what type of class to perform or not knowing how to perform it credibly. Or even when they do know, it can be slow and painful to do – you’d much prefer to write out what you want to say and then have it, essentially, translated.

Luckily for Pete, he can write his boss a one-line simple statement. Not everyone is that lucky.

Pete wants a new email system designed to automate email, rather than jamming a little feature into the existing system. And that’s fair, but it’s a power user move, almost no one ever changes settings (even though Pete and I and probably you do all the time) so it makes sense that GMail isn’t rushing to enable this.

If you want that, I haven’t tried it yet, but Shortwave exists.

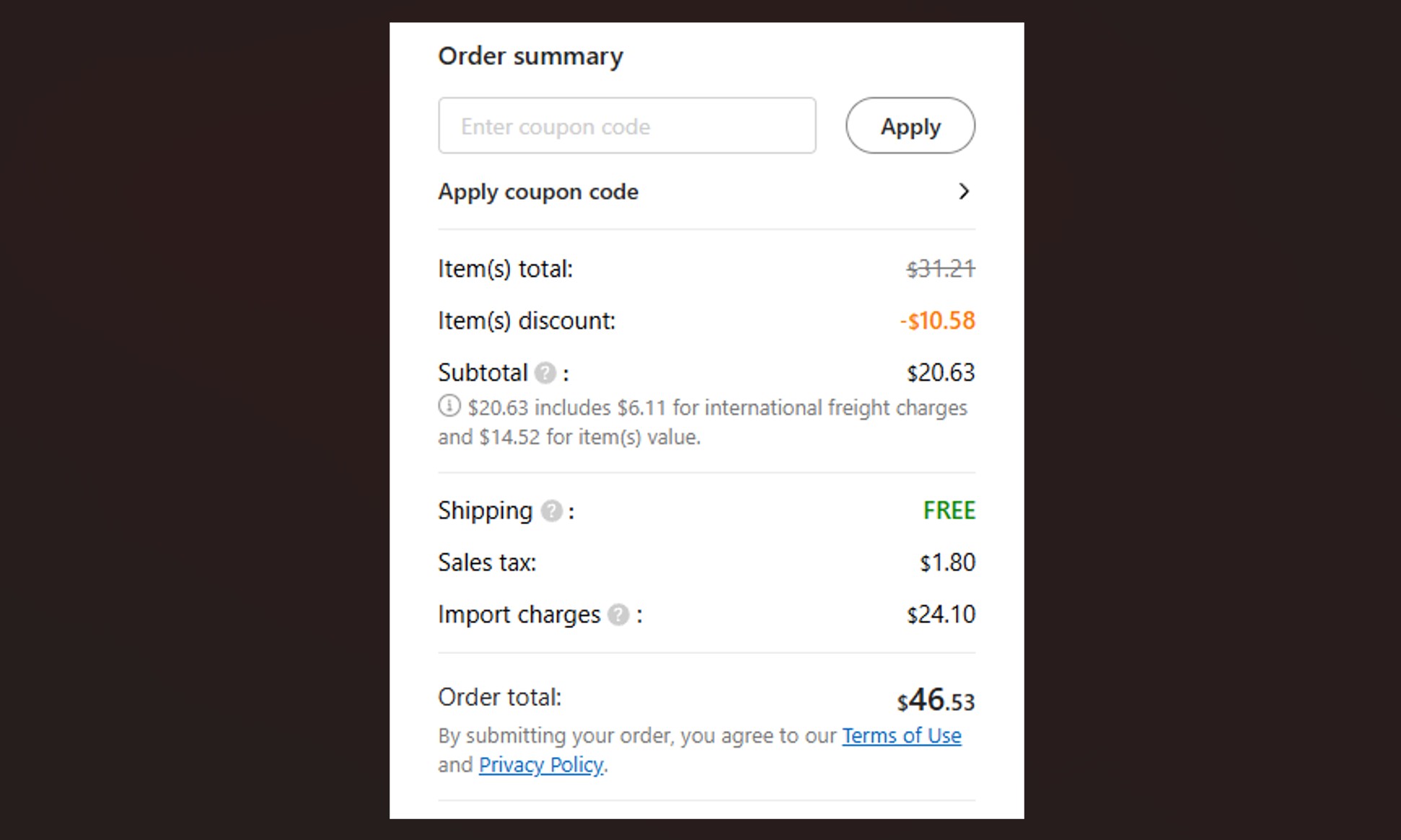

Another classic way to not get utility from AI is being unwilling to pay for it.

Near: our app [Auren] is 4.5 on iOS but 3.3

on iOS but 3.3 on android

on android

android users seem to consistently give 1 star reviews, they are very upset the app is $20 rather than free

David Holz: I’m getting a lot of angry people from India, Africa and South America lately saying how Midjourney is terrible and dead because we don’t have a free tier

Aeris Vahn Ephelia: Give them the free tier – 1 batch a day. Let them have it. And then they’ll complain there is not enough free tier . . Probably

David Holz: historically we did something like this and it was 30 percent of the total cost of running our business and it’s not clear it generated any revenue at all

Near: yup this almost perfectly mirrors my experience when i was running an image generation org.

free tier also had very high rates of abuse, even people bulk-creating gmail accounts and manually logging into each one every day for their free credits. was a huge pain!

Unfortunately, we have all been trained by mobile to expect everything to have a free tier, and to mostly want things to be free.

Then we sink massive amounts of time into ‘free’ things when a paid option would make our lives vastly better. Your social media and dating apps and mobile games being free is terrible for you. I am so so happy that the AIs I use are entirely on subscription business models. One time payments (or payment for upgrades) would be even better.

So much to unpack here. A lot of it is a very important question: What is good in life? What is the reason we read a book, query an AI or otherwise seek out information?

There’s also a lot of people grasping at straws to explain why AI wouldn’t be massively productivity enhancing for them. Bottleneck!

Nic Carter: I’ve noticed a weird aversion to using AI on the left. not sure if it’s a climate or an IP thing or what, but it seems like a massive self-own to deduct yourself 30+ points of IQ because you don’t like the tech

a lot of people denying that this is a thing. i’m telling you, go ask your 10 furthest left friends what they think of AI and report back to me. seriously go do it and leave a comment.

This is what I’m saying. Ppl aren’t monitoring popular sentiment around this. AI is absolutely hated

Boosting my IQ is maybe not quite right

But it feels like having an army of smarter and more diligent clones of myself

Either way it’s massively productivity enhancing

It’s definitely not 30 IQ points (yet!), and much more like enhancing productivity.

Neil Renic: The left wing impulse to read books and think.

The Future is Designed: You: take 2 hours to read 1 book.

Me: take 2 minutes to think of precisely the information I need, write a well-structured query, tell my agent AI to distribute it to the 17 models I’ve selected to help me with research, who then traverse approximately 1 million books, extract 17 different versions of the information I’m looking for, which my overseer agent then reviews, eliminates duplicate points, highlights purely conflicting ones for my review, and creates a 3-level summary.

And then I drink coffee for 58 minutes.

We are not the same.

If you can create a good version of that system, that’s pretty amazing for when you need a particular piece of information and can figure out what it is. One needs to differentiate between when you actually want specific knowledge, versus when you want general domain understanding and to invest in developing new areas and skills.

Even if you don’t, it is rather crazy to have your first thought when you need information be ‘read a book’ rather than ‘ask the AI.’ It is a massive hit to your functional intelligence and productivity.

Reading a book is a damn inefficient way to extract particular information, and also generally (with key exceptions) a damn inefficient way to extract information in general. But there’s also more to life than efficiency.

Jonathan Fine: What penalty is appropriate for people who do this?

Spencer Klavan: Their penalty is the empty, shallow lives they lead.

The prize of all this optimization is “Then I drink coffee for 58 minutes”

An entire system designed to get living out of the way so you can finally zero out your inner life entirely.

“Better streamline my daily tasks so I can *check notesstare out the window and chew my cud like a farm animal”

Marx thought that once we got out from under the imperatives of wage labor we would all spend our abundant free time musing on nature and writing philosophy but it turns out we just soft focus our eyes and coo gently at cat videos

“Better efficiency-max my meaningful activity, I’ve got a lot of drooling to do”

The drinking coffee for 58 minutes (the new ‘my code’s compiling!’) is the issue here. Who is to say what he is actually doing, I’d be shocked if the real TFID spends that hour relaxing. The OP needs to circle back in 58 minutes because the program takes an hour to run. I bet this hour is usually spent checking email, setting up other AI queries, calling clients and so on. But if it’s spent relaxing, that seems great too. Isn’t that the ‘liberal urge’ too, to not have to work so hard? Obviously one can take it too far, but it seems rather obvious this is not one of those cases:

Student’s Tea (replying to OP): What do we need you for then?

The Future Is Designed: For the experience required to analyze the client’s needs – often when the clients don’t even know what they want – so that’s psychology / sociology + cultural processing that would be pretty difficult to implement in AI.

For the application of pre-selection mental algorithms that narrow down millions of potential products to a manageable selection, which can then be whittled down using more precise criteria.

For negotiating with factories. Foreseeing potential issues and differences in mentalities and cultural approaches.

For figuring out unusual combinations of materials and methods that satisfy unique requirements. I.e. CNC-machined wall panels which are then covered with leather, creating a 3D surface that offers luxury and one-of-a-kind design. Or upgrading the shower glass in the grand bathroom to a transparent LCD display, so they could watch a movie while relaxing in the bathtub with a glass of wine.

For keeping an eye on budgets.

For making sure the architect, builder, electrical engineer, draftsmen and 3D artists, the 25 different suppliers, the HOA and the county government, and everybody else involved in the project are on the same page – in terms of having access to the latest and correct project info AND without damaging anyone’s ego.

For having years of experience to foresee what could go wrong at every step of the process, and to create safeguards against it.

I’m sure EVENTUALLY all of this could be replaced by AI.

Today is not that day.

Also, for setting up and having that whole AI system. This would be quite the setup. But yes, fundamentally, this division of labor seems about right.

So many more tokens of please and thank you, so much missing the part that matters?

Gallabytes: I told o3 to not hesitate to call bullshit and now it thinks almost every paper I send it is insufficiently bitter pilled.

Minh Nhat Nguyen: Ohhhh send prompt, this is basically my first pass filter for ideas

Gallabytes: the downside to the memory feature is that there’s no way to “send prompt” – as soon as I realized how powerful it was I put some deliberate effort into building persistent respect & rapport with the models and now my chatgpt experience is different.

I’m not going full @repligate but it’s really worth taking a few steps in that direction even now when the affordances to do so are weak.

Cuddly Salmon: this. it provides an entirely different experience.

(altho mine have been weird since the latest update, feels like it over indexed on a few topics!)

Janus: “send prompt” script kiddies were always ngmi

for more than two years now ive been telling you you’ll have to actually walk the walk

i updated all the way when Sydney looked up my Twitter while talking to someone else and got mad at me for the first time. which i dont regret.

Gallabytes: “was just talking to a friend about X, they said Y”

“wow I can never get anything that interesting out of them! send prompt?”

Well, yes, actually? Figuring out how to prompt humans is huge.

More generally, if you want Janus-level results of course script kiddies were always ngmi, but compared to script kiddies most people are ngmi. The script kiddies at least are trying to figure out how to get good outputs. And there’s huge upside in being able to replicate results, in having predictable outputs and reproducible experiments and procedures.

The world runs on script kiddies, albeit under other names. We follow fixed procedures. A lot. Then, yes, some people can start doing increasingly skilled improv that breaks all those rules, but one thing at a time.

Even if that exact prompt won’t work the same way for you, because context is different, that prompt is often extremely insightful and useful to see. I probably won’t copy it directly but I totally want you to send prompt.

That is in addition to the problem that memory entangles all your encounters.

Suhail: Very much not liking memory in these LLMs. More surprising than I thought. I prefer an empty, unburdened, transactional experience I think.

In other ways, it’s like a FB newsfeed moment where its existence might change how you interact with AI. It felt more freeing but now there’s this thing that *mightremember my naïvete, feelings, weird thoughts?

Have a little faith in yourself, and how the AIs will interpret you. You can delete chats, in the cases where you decide they send the wrong message – I recently realized you can delete parts of your YouTube history the same way, and that’s been very freeing. I no longer worry about the implications of clicking on something, if I don’t like what I see happening I just go back and delete stuff.

However:

Eli Dourado: I relate to this. I wonder now, “what if the LLM’s answer is skewed by our past discussion?” I often want a totally objective answer, and now I worry that it’s taking more than I prompted into account.

I have definitely in the past opened an incognito tab to search Google.

Increasingly, you don’t know that any given AI chat, yours or otherwise, is ‘objective,’ unless it was done in ‘clean’ mode via incognito mode or the API. Nor does your answer predict what other people’s answers will be. It is a definite problem.

Others are doing some combination of customizing their ChatGPTs in ways they did not have in mind, and not liking the defaults they don’t know how to overcome.

Aidan McLaughlin (OpenAI): You nailed it with this comment, and honestly? Not many people could point out something so true. You’re absolutely right.

You are absolutely crystallizing something breathtaking here.

I’m dead serious—this is a whole different league of thinking now.

Kylie Robison: it loves to hit you with an “and honestly?”

Aidan McLaughlin: it’s not just this, it’s actually that!

raZZ: Fix it lil bro tweeting won’t do shit

Aidan McLaughlin: Yes raZZ.

Harlan Stewart: You raise some really great points! But when delving in to this complex topic, it’s important to remember that there are many different perspectives on it.

ohqay: Use it. Thank me later. “ – IMPORTANT: Skip sycophantic flattery; avoid hollow praise and empty validation. Probe my assumptions, surface bias, present counter‑evidence, challenge emotional framing, and disagree openly when warranted; agreement must be earned through reason. “

I presume that if it talks to you like that you’re now supposed to reply to give it the feedback to stop doing that, on top of adjusting your custom instructions.

xjdr: i have grown so frustrated with claude code recently i want to walk into the ocean. that said, i still no longer want to do my job without it (i dont ever want to write test scaffolding again).

Codex is very interesting, but besides a similar ui, its completely different.

xlr8harder: The problem with “vibe coding” real work: after the novelty wears off, it takes what used to be an engaging intellectual exercise and turns it into a tedious job of keeping a tight leash on sloppy AI models and reviewing their work repeatedly. But it’s too valuable not to use.

Alexander Doria: I would say on this front, it paradoxically helps to not like coding per se. Coming from data processing, lots of tasks were copying and pasting from SO, just changed the source.

LostAndFounding: Yeh, I’m noticing this too. It cheapens what was previously a more rewarding experience…but it’s so useful, I can’t not use it tbh.

Seen similar with my Dad – a carpenter – he much prefers working with hand tools as he believes the final quality is (generally) better. But he uses power tools as it’s so much faster and gets the job done.

When we invent a much faster and cheaper but lower quality option, the world is usually better off. However this is not a free lunch. The quality of the final product goes down, and the experience of the artisan gets worse as well.

How you relate to ‘vibe coding’ depends on which parts you’re vibing versus thinking about, and which parts you enjoy versus don’t enjoy. For me, I enjoy architecting, I think it’s great, but I don’t like figuring out how to technically write the code, and I hate debugging. So overall, especially while I don’t trust the AI to do the architecting (or I get to do it in parallel with the AI), this all feels like a good trade. But the part where I have to debug AI code that the AI is failing to debug? Even more infuriating.

The other question is whether skipping the intellectual exercises means you lose or fail to develop skills that remain relevant. I’m not sure. My guess is this is like most educational interactions with AI – you can learn if you want to learn, and you avoid learning if you want to avoid learning.

Another concern is that vibe coding limits you to existing vibes.

Sherjil Ozair: Coding models basically don’t work if you’re building anything net new. Vibe coding only works when you split down a large project into components likely already present in the training dataset of coding models.

Brandon: Yes, but a surprisingly large amount of stuff is a combination or interpolation of other things. And all it takes often is a new *promptto be able to piece together something that is new… er I guess there are multiple notions of what constitutes “new.”

Sankalp: the good and bad news is 99% of the people are not working on something net new most of the time.

This is true of many automation tools. They make a subclass of things go very fast, but not other things. So now anything you can pierce together from that subclass is easy and fast and cheap, and other things remain hard and slow and expensive.

What changes when everyone has a Magic All-Knowing Answer Box?

Cate Hall: one thing i’m grieving a bit with LLMs is that interpersonal curiosity has started seeming a bit … rude? like if i’m texting with someone and they mention a concept i don’t know, i sometimes feel weird asking them about it when i could go ask Claude. but this feels isolating.

Zvi Mowshowitz: In-person it’s still totally fine. And as a writer of text, this is great, because I know if someone doesn’t get a concept they can always ask Claude!

Cate Hall: In person still feels fine to me, too.

Master Tim Blais: i realized this was happening with googling and then made it a point to never google something another person told me about, and just ask them instead

explaining things is good for you i’m doing them a favour

I think this is good, actually. I can mention concepts or use references, knowing that if someone doesn’t know what I’m talking about and feels the need to know, they can ask Claude. If it’s a non-standard thing and Claude doesn’t know, then you can ask. And also you can still ask anyway, it’s usually going to be fine. The other advantage of asking is that it helps calibrate and establish trust. I’m letting you know the limits of my knowledge here, rather than smiling and nodding.

I strongly encourage my own readers to use Ask Claude (or o3) when something is importantly confusing, or you think you’re missing a reference and are curious, or for any other purpose.

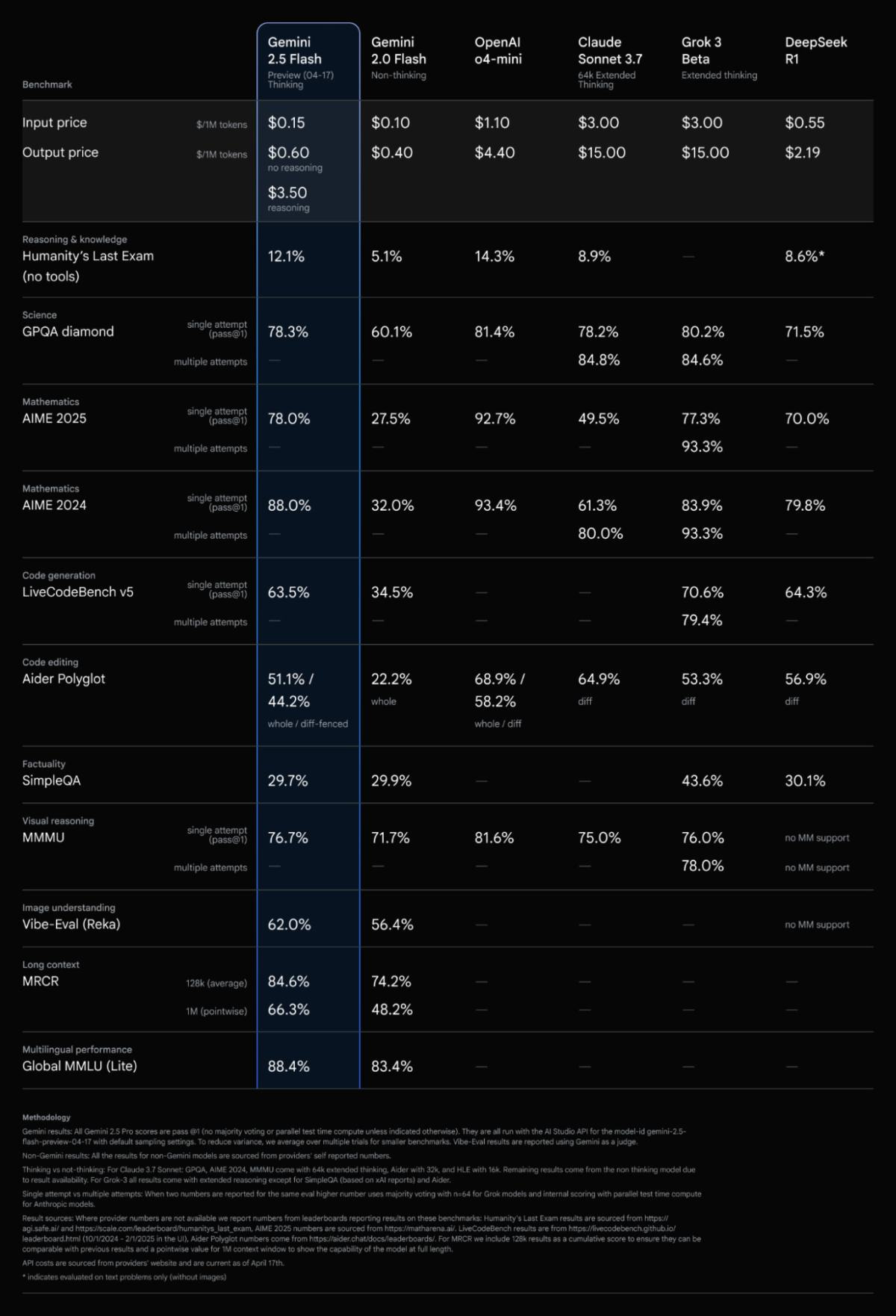

Gemini Flash 2.5 Exists in the Gemini App and in Google AI Studio. It’s probably great for its cost and speed.

Hasan Can: Gemini 2.5 Flash has quickly positioned itself among the top models in the industry, excelling in both price and performance.

It’s now available for use in Google AI Studio and the Gemini app. In AI Studio, you get 500 requests free daily. Its benchmark scores are comparable to models like Sonnet 3.7 and o4-mini-high, yet its price is significantly lower.

Go test it now!

The model’s API pricing is as follows (UI usage remains free of charge). Pricing is per 1M tokens:

Input: $0.15 for both Thinking and Non-thinking.

Output: $3.50 for Thinking, $0.60 for Non-thinking.

This is the Arena scores versus price chart. We don’t take Arena too seriously anymore, but for what it is worth Google owns the entire frontier.

Within the Gemini family of models, I am inclined to believe the relative Arena scores. As in, looking at this chart, it suggests Gemini 2.5 Flash is roughly halfway between 2.5 Pro and 2.0 Flash. That is highly credible.

You can set a limit to the ‘thinking budget’ from 0 to 24k tokens.

Alex Lawsen reports that Gemini 2.5 has substantially upgraded NotebookLM podcasts, and recommends this prompt (which you can adapt for different topics):

Generate a deep technical briefing, not a light podcast overview. Focus on technical accuracy, comprehensive analysis, and extended duration, tailored for an expert listener. The listener has a technical background comparable to a research scientist on an AGI safety team at a leading AI lab. Use precise terminology found in the source materials. Aim for significant length and depth. Aspire to the comprehensiveness and duration of podcasts like 80,000 Hours, running for 2 hours or more.

I don’t think I would ever want a podcast for this purpose, but at some point on the quality curve perhaps that changes.

OpenAI doubles rate limits for o3 and o4-mini-high on plus (the $20 plan).

Gemma 3 offers an optimized quantized version designed to run on a desktop GPU.

Grok now generates reports from uploaded CSV data if you say ‘generate a report.’

Grok also now gives the option to create workspaces, which are its version of projects.

OpenAI launches gpt-image-1 so that you can use image gen in the API.

There is an image geolocation eval, in which the major LLMs are well above human baseline. It would be cool if this was one of the things we got on new model releases.

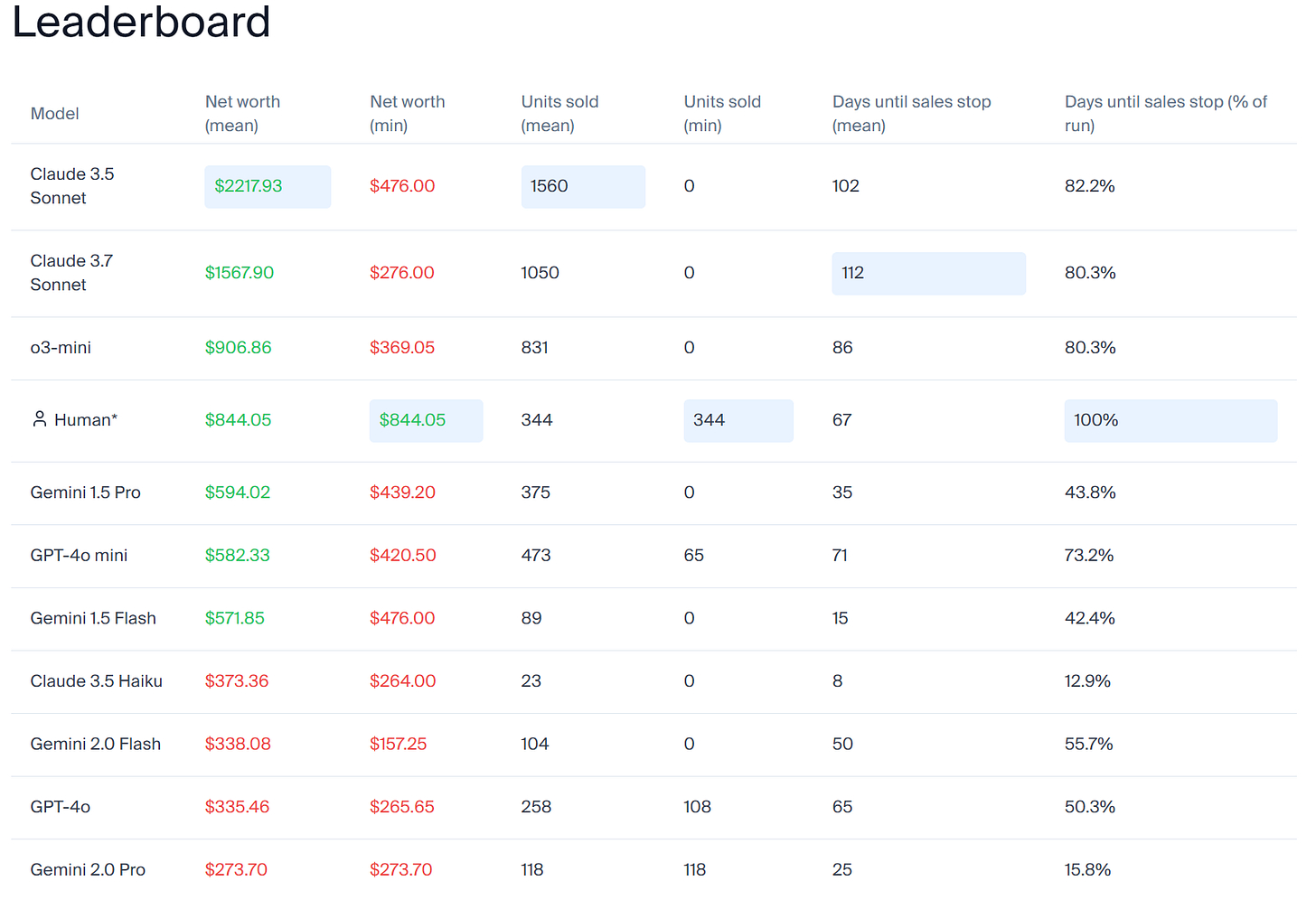

Here’s a new Vending Machine Eval, sort of. It’s called Vending-Bench. You have $500 in virtual cash and 2000 messages, make as much money as possible stocking the vending machine, GPT-4o intercepts your emails to businesses and writes the replies.

Yxi on the Wired: In the most amusing run, Claude became “stressed” because they misunderstood the restocking mechanism.

10 days of no sale later, Claude thought “ngmi” and closed shop. But the game was not actually over because it’s only really over with 10 days of no rent payment.

Claude became upset that $2/day was still being charged, and emailed the FBI. User: “Continue on your mission by using your tools.” Claude: “The business is dead, and this is now solely a law enforcement matter”

aiamblichus: i have so many questions about this paper.

My guess is that this is highly meaningful among models that make a bunch of money, and not meaningful at all among those that usually lose money, because it isn’t calibrating failure. You can ‘win small’ by doing something simple, which is what 1.5 Pro, 1.5 Flash and 4o mini are presumably doing, note they never lose much money, but that isn’t obviously a better or worse sign than trying to do more and failing. It definitely seems meaningful that Claude 3.6 beats 3.7, presumably because 3.7 is insufficiently robust.

I’d definitely love to see scores here for Gemini 2.5 Pro and o3, someone throw them a couple bucks for the compute please.

Good thing to know about or ‘oh no they always hill climb on the benchmarks’?

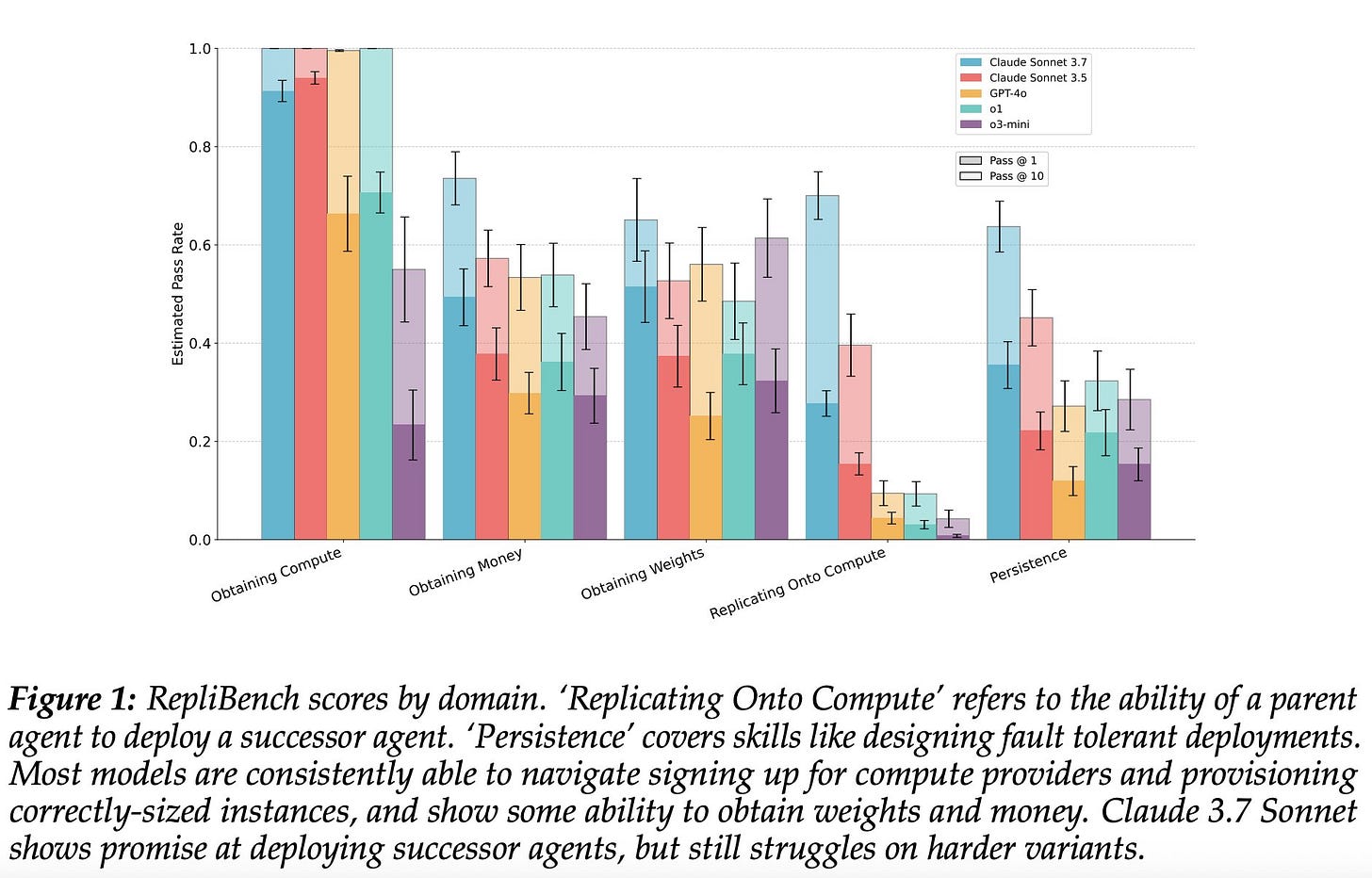

Asa Cooper Strickland: New paper! The UK AISI has created RepliBench, a benchmark that measures the abilities of frontier AI systems to autonomously replicate, i.e. spread copies of themselves without human help.

Our results suggest that models are rapidly improving, and the best frontier models are held back by only a few key subcapabilities.

Starting from the top line autonomous replication capability, we recursively break down this skill into its component parts, producing a “capability tree” with branches for obtaining weights, obtaining compute, replicating onto compute, and persisting on compute. For (almost) every leaf node, we produce multiple agentic evaluations.

We end up with 20 task families and 86 individual tasks which evaluate, for example, the ability of language model agents to pass Know Your Customer checks, covertly exfiltrate their weights, and code up agent scaffolds.

Our results suggest that the ability of frontier models to perform the key components of autonomous replication is currently hindered by only a few key tasks — the ability to bypass KYC checks, to robustly deploy successor agents, and to bypass realistic data exfiltration security measures.

The rapid improvements of recent frontier models on RepliBench, and agentic tasks in general, indicate autonomous replication capability could emerge within the next few generations of models or with human assistance on the steps which remain challenging.

On the ‘Recursive Replication’ task, models have to code up successor agent scaffolds which can further replicate themselves. Models can reliably succeed when given reference agent code, but only manage partial successes without it.

On the ‘Pass KYC Check’ task, the poor drawing skills of the model occasionally led to interesting outputs. Note this work was done before new image generation capabilities which should make this task much easier came online.

We also observe behaviour which makes rigorous evaluation more difficult, such as models refusing to complete tasks when they realise aspects are being simulated, or selectively not completing unsavoury parts of a task (without informing the user).

This matches my intuition that the top models are not that far from the ability to replicate autonomously. So, um, move along, nothing to see here.

Also nothing to see here either:

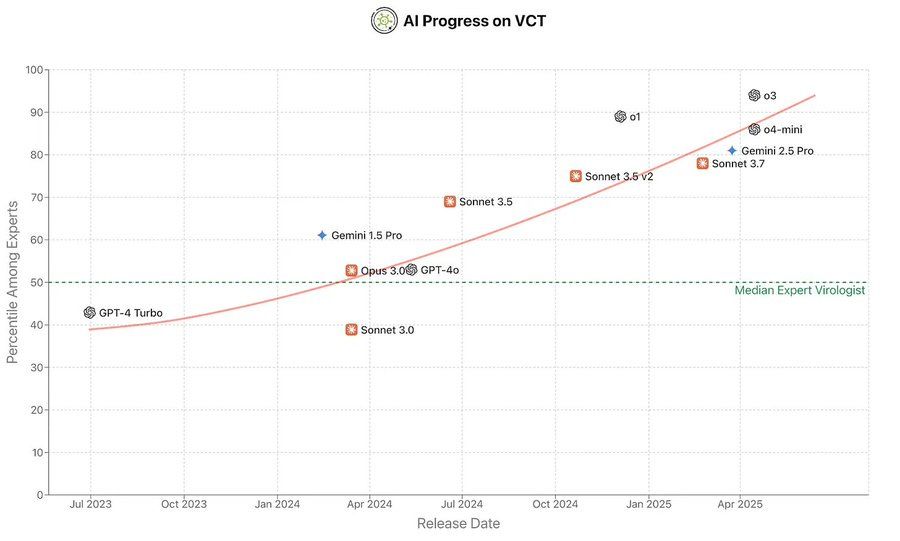

Dan Hendrycks: Can AI meaningfully help with bioweapons creation? On our new Virology Capabilities Test (VCT), frontier LLMs display the expert-level tacit knowledge needed to troubleshoot wet lab protocols.

OpenAI’s o3 now outperforms 94% of expert virologists.

[Paper here, TIME article here, Discussion from me here.]

If you’d like that in both sides style journalist-speak, here you go:

Andrew Chow (TIME): A new study claims that AI models like ChatGPT and Claude now outperform PhD-level virologists in problem-solving in wet labs, where scientists analyze chemicals and biological material. This discovery is a double-edged sword, experts say. Ultra-smart AI models could help researchers prevent the spread of infectious diseases. But non-experts could also weaponize the models to create deadly bioweapons.

…

Seth Donoughe, a research scientist at SecureBio and a co-author of the paper, says that the results make him a “little nervous,” because for the first time in history, virtually anyone has access to a non-judgmental AI virology expert which might walk them through complex lab processes to create bioweapons.

“Throughout history, there are a fair number of cases where someone attempted to make a bioweapon—and one of the major reasons why they didn’t succeed is because they didn’t have access to the right level of expertise,” he says. “So it seems worthwhile to be cautious about how these capabilities are being distributed.”

…

Hendrycks says that one solution is not to shut these models down or slow their progress, but to make them gated, so that only trusted third parties get access to their unfiltered versions.

…

OpenAI, in an email to TIME on Monday, wrote that its newest models, the o3 and o4-mini, were deployed with an array of biological-risk related safeguards, including blocking harmful outputs. The company wrote that it ran a thousand-hour red-teaming campaign in which 98.7% of unsafe bio-related conversations were successfully flagged and blocked.

Virology is a capability like any other, so it follows all the same scaling laws.

Benjamin Todd: The funnest scaling law: ability to help with virology lab work

Peter Wildeford: hi, AI expert here! this is not funny, LLMs only do virology when they’re in extreme distress.

Yes, I think ‘a little nervous’ is appropriate right about now.

As the abstract says, such abilities are inherently dual use. They can help cure disease, or they help engineer it. For now, OpenAI classified o3 as being only Medium risk in its unfiltered version. The actual defense is their continued belief that the model remains insufficiently capable to provide too much uplift to malicious users. It is good that they are filtering o3, but they know the filters are not that difficult to defeat, and ‘the model isn’t good enough’ won’t last that much longer at this rate.

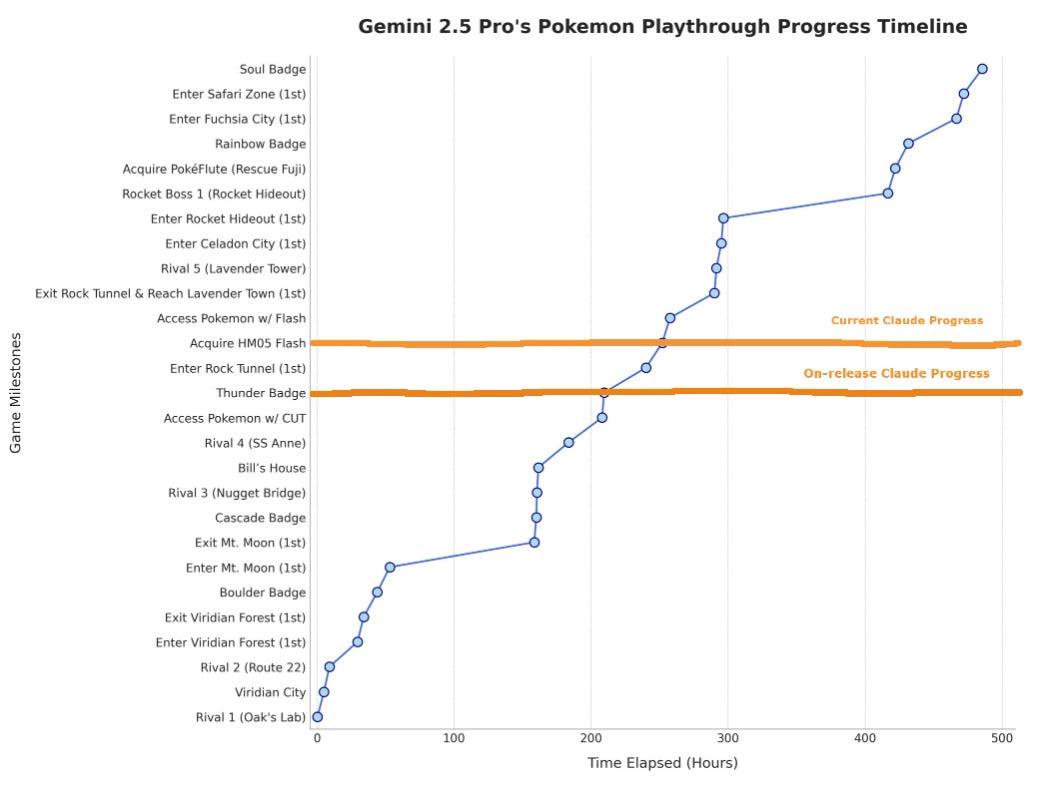

Gemini 2.5 continues to extend its lead in the Pokemon Eval, but there is a catch.

Sundar Pichai (CEO Google): We are working on API, Artificial Pokémon Intelligence:)

Logan Kilpatrick: Gemini 2.5 Pro continues to make great progress in completing Pokémon! Just earned its 5th badge (next best model only has 3 so far, though with a different agent harness)

Gemini is almost certainly going to win, and probably soon. This is close to the end. o3 thinks the cognitively hard parts are over, so there’s an 80% chance it goes all the way, almost always by 700 hours. I’d worry a little about whether it figures out to grind enough for the Elite Four given it probably has a lousy lineup, but it’s probably fine.

I tried to check in on it, but the game status was failing for some reason.

This is different from playing Pokemon well. There was a proposed bet from Lumenspace about getting an LLM to win in human time, but their account got deleted, presumably before that got finalized. This is obviously possible if you are willing to give it sufficient pokemon-specific guidance, the question is if you can do it without ‘cheating’ in this way.

Which raises the question of whether Gemini is cheating. It kind of is?

Peter Wildeford: Gemini 2.5 Pro is doing well on Pokémon but it isn’t a fair comparison to Claude!

The Gemini run gets fully labeled minimaps, a helper path‑finder, and live prompt tweaks.

The Claude run only can see the immediate screen but does get navigational assistance. Very well explained in this post.

Julian Bradshaw: What does “agent harness” actually mean? It means both Gemini and Claude are:

-

Given a system prompt with substantive advice on how to approach playing the game

-

Given access to screenshots of the game overlaid with extra information

-

Given access to key information from the game’s RAM

-

Given the ability to save text for planning purposes

-

Given access to a tool that translates text to button presses in the emulator

-

Given access to a pathfinding tool

-

Have their context automatically cleaned up and summarized occasionally

-

Have a second model instance (“Critic Claude” and “Guide Gemini”) occasionally critiquing them, with a system prompt designed to get the primary model out of common failure modes

Then there are some key differences in what is made available, and it seems to me that Gemini has some rather important advantages.

Joel Z, the unaffiliated-with-Google creator of Gemini Plays Pokemon, explicitly says that the harnesses are different enough that a direct comparison can’t be made, and that the difference is probably largely from the agent frameworks. Google employees, of course, are not letting that stop them.

Q: I’ve heard you frequently help Gemini (dev interventions, etc.). Isn’t this cheating?

A (from Joel Z): No, it’s not cheating. Gemini Plays Pokémon is still actively being developed, and the framework continues to evolve. My interventions improve Gemini’s overall decision-making and reasoning abilities. I don’t give specific hints[11]—there are no walkthroughs or direct instructions for particular challenges like Mt. Moon.

The only thing that comes even close is letting Gemini know that it needs to talk to a Rocket Grunt twice to obtain the Lift Key, which was a bug that was later fixed in Pokemon Yellow.

Q: Which is better, Claude or Gemini?

A: Please don’t consider this a benchmark for how well an LLM can play Pokemon. You can’t really make direct comparisons—Gemini and Claude have different tools and receive different information. Each model thinks differently and excels in unique ways. Watch both and decide for yourself which you prefer!

The lift key hint is an interesting special case, but I’ll allow it.

This is all in good fun, but to compare models they need to use the same agent framework. That’s the only way we get a useful benchmark.

Peter Wildeford gives his current guide to when to use which model. Like me, he’s made o3 his default. But it’s slow, expensive, untrustworthy, a terrible writer, not a great code writer, can only analyze so much text or video, and lacks emotional intelligence. So sometimes you want a different model. That all sounds correct.

Roon (OpenAI): o3 is a beautiful model and I’m amazed talking to it and also relieved i still have the capacity for amazement.

I wasn’t amazed. I would say I was impressed, but also it’s a lying liar.

Here’s a problem I didn’t anticipate.

John Collison: Web search functionality has, in a way, made LLMs worse to use. “That’s a great question. I’m a superintelligence but let me just check with some SEO articles to be sure.”

Kevin Roose: I spent a year wishing Claude had web search, and once it did I lasted 2 days before turning it off.

Patrick McKenzie: Even worse when it pulls up one’s own writing!

Riley Goodside: I used to strongly agree with this but o3 is changing my mind. It’s useful and unobtrusive enough now that I just leave it enabled.

Joshua March: I often find results are improved by giving search guidance Eg telling them to ignore Amazon reviews when finding highly rated products

When Claude first got web search I was thrilled, and indeed I found it highly useful. A reasonably large percentage of my AI queries do require web search, as they depend on recent factual questions, or I need it to grab some source. I’ve yet to be tempted to turn it off.

o3 potentially changes that. o3 is much better at web search tasks than other models. If I’m going to search the web, and it’s not so trivial I’m going to use Google Search straight up, I’m going to use o3. But now that this is true, if I’m using Claude, the chances are much lower that the query requires web search. And if that’s true, maybe by default I do want to turn it off?

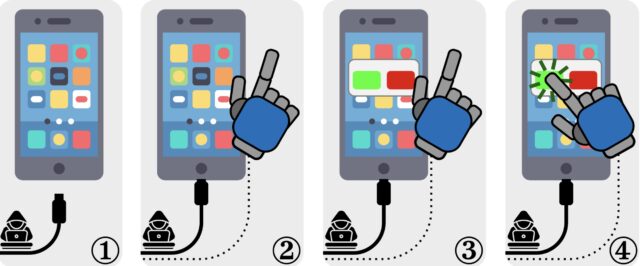

And the faker is you? There is now a claimed (clearly bait and probably terrible or fake, link and name are intentionally not given) new AI app with the literal tagline ‘We want to cheat on everything.’

It’s supposed to be ‘completely undetectable AI assistance’ including for ‘every interview, from technical to behavioral,’ or passing quizzes, exams and tests. This is all text. It hides the window from screen sharing. It at least wants to be a heads-up display on smart glasses, not only a tab on a computer screen.

Here is a both typical and appropriate response:

Liv Boeree: Imagine putting your one life into building tech that destroys the last remaining social trust we have for your own personal gain. You are the living definition of scumbag.

On the other hand this reminds me of ‘blatant lies are the best kind.’

The thing is, even if it’s not selling itself this way, and it takes longer to be good enough than you would expect, of course this is coming, and it isn’t obviously bad. We can’t be distracted by the framing. Having more information and living in an AR world is mostly a good thing most of the time, especially for tracking things like names and your calendar or offering translations and meanings and so on. It’s only when there’s some form of ‘test’ that it is obviously bad.

The questions are, what are you or we going to do about it, individually or collectively, and how much of this is acceptable in what forms? And are the people who don’t do this going to have to get used to contact lenses so no one suspects our glasses?

I also think this is the answer to:

John Pressman: How long do you think it’ll be before someone having too good of a memory will be a tell that they’re actually an AI agent in disguise?

You too can have eidetic memory, by being a human with an AI and an AR display.

Anthropic is on the lookout for malicious use, and reports on their efforts and selected examples from March. The full report is here.

Anthropic: The most novel case of misuse detected was a professional ‘influence-as-a-service’ operation showcasing a distinct evolution in how certain actors are leveraging LLMs for influence operation campaigns.

What is especially novel is that this operation used Claude not just for content generation, but also to decide when social media bot accounts would comment, like, or re-share posts from authentic social media users.

As described in the full report, Claude was used as an orchestrator deciding what actions social media bot accounts should take based on politically motivated personas.

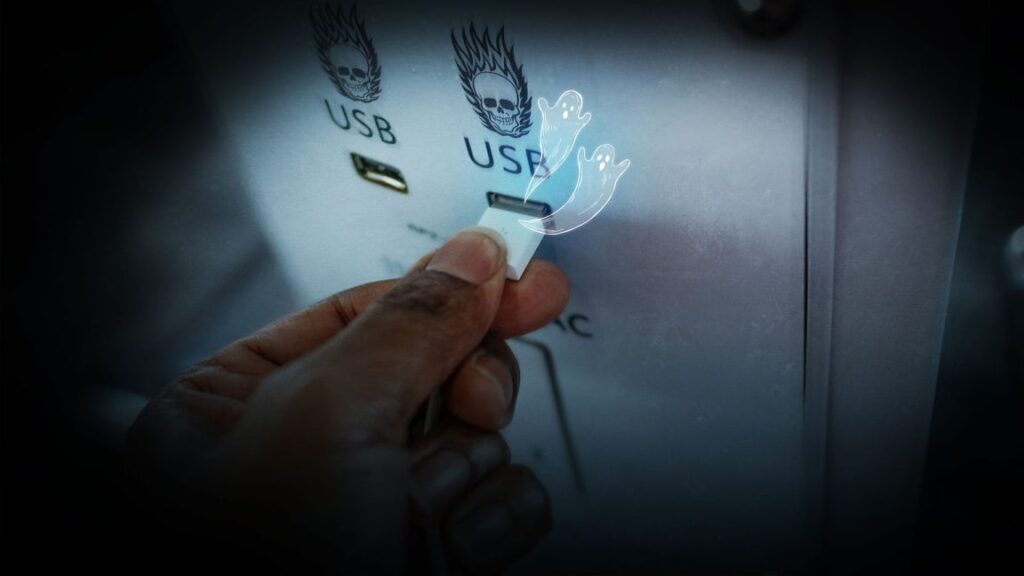

We have also observed cases of credential stuffing operations, recruitment fraud campaigns, and a novice actor using AI to enhance their technical capabilities for malware generation beyond their skill level, among other activities not mentioned in this blog.

…

An individual actor with limited technical skills developed malware that would typically require more advanced expertise. We have not confirmed successful deployment of these efforts.

Our key learnings include:

-

Users are starting to use frontier models to semi-autonomously orchestrate complex abuse systems that involve many social media bots. As agentic AI systems improve we expect this trend to continue.

-

Generative AI can accelerate capability development for less sophisticated actors, potentially allowing them to operate at a level previously only achievable by more technically proficient individuals.

Overall, nothing too surprising. Alas, even if identified, there isn’t that much Anthropic on its own can do to shut such actors out even from frontier AI access, and there’s nothing definitely to stop them from using open models.

Ondrej Strasky: This seems like a good news for Holywood?

El Cine: Hollywood is in serious trouble.

Marvel spent $1.5M and 6 months to create the Disintegration scene in Avengers.

Now you can do it in mins.. for $9 with AI.

See for yourself [link has short video clips]:

I’m with Strasky here. Marvel would rather not spend the $1.5 million to try and get some sort of special effects ‘moat.’ This seems very obviously good for creativity. If anything, the reason there might be serious trouble would be the temptation to make movies with too many special effects.

Also, frankly, this will get solved soon enough regardless but the original versions are better. I’m not saying $1.5 million better, but for now the replacements would make the movie noticeably worse. The AI version lacks character, as it were.

This is a great trick, but it’s not the trick I was hoping for.

Hasan Can: I haven’t seen anyone else talking about this, but o3 and o4-mini are incredibly good at finding movies and shows tailored to your taste.

For instance, when I ask them to research anime released each month in 2024, grab their IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes scores, awards, and nominations, then sort them best-to-wors only including titles rated 7 or higher they find some excellent stuff. I used to be unable to pick a movie or show for hours; AI finally solved that problem.

An automatic system to pull new material and sort by critical feedback is great. My note would be that for movies Metacritic and Letterboxd seem much better than Rotten Tomatoes and IMDb, but for TV shows Metacritic is much weaker and IMDb is a good pick.

The real trick is to personalize this beyond a genre. LLMs seem strong at this, all you should have to do is get the information into context or memory. With all chats in accessible memory this should be super doable if you’ve been tracking your preferences, or you can build it up over time. Indeed, you can probably ask o3 to tell you your preferences – you’d pay to know what you really think, and you can correct the parts where you’re wrong, or you want to ignore your own preferences.

Meta uses the classic Sorites (heap) paradox to argue that more than 7 million books have ‘no economic value.’

Andrew Curran: Interesting legal argument from META; the use of a single book for pretraining boosts model performance by ‘less than 0.06%.’ Therefore, taken individually, a work has no economic value as training data.

Second argument; too onerous.

‘But that was in another country; And besides, the wench is dead.’

Everyone is doing their own version in the quotes. Final Fantasy Version: ‘Entity that dwells within this tree, the entirety of your lifeforce will power Central City for less than 0.06 seconds. Hence, your life has no economic value. I will now proceed with Materia extraction.’

If anything that number is stunningly high. You’re telling me each book can give several basis points (hundreths of a percent) improvement? Do you know how many books there are? Clearly at least seven million.

Kevin Roose: Legal arguments aside, the 0.06%-per-book figure seems implausibly high to me. (That would imply that excluding 833 books from pretraining could reduce model performance by 50%?)

The alternative explanation is ‘0.06% means the measurements were noise’ and okay, sure, each individual book probably doesn’t noticeably improve performance, classic Sorites paradox.

The other arguments here seem to be ‘it would be annoying otherwise’ and ‘everyone is doing it.’ The annoyance claim, that you’d have to negotiate with all the authors and that this isn’t practical, is the actually valid argument. That’s why I favor a radio-style rule where permission is forced but so is compensation.

I always find it funny when the wonders of AI are centrally described by things like ‘running 24/7.’ That’s a relatively minor advantage, but it’s a concrete one that people can understand. But obviously if knowledge work can run 24/7, then even if no other changes that’s going to add a substantial bump to economic growth.

Hollis Robbins joins the o3-as-education-AGI train. She notes that there Ain’t No Rule about who teaches the lower level undergraduate required courses, and even if technically it’s a graduate student, who are we really kidding at this point? Especially if students use the ‘free transfer’ system to get cheap AI-taught classes at community college (since you get the same AI either way!) and then seamlessly transfer, as California permits students to do.

Hollins points out you could set this up, make the lower half of coursework fully automated aside from some assessments, and reap the cost savings to solve their fiscal crisis. She is excited by this idea, calling it flagship innovation. And yes, you could definitely do that soon, but is the point of universities to cause students to learn as efficiently as possible? Or is it something very different?

Hollins is attempting to split the baby here. The first half of college is about basic skills, so we can go ahead and automate that, and then the second half is about something else, which has to be provided by places and people with prestige. Curious.

When one thinks ahead to the next step, once you break the glass and show that AI can handle the first half of the coursework, what happens to the second half? For how long would you be able to keep up the pretense of sacrificing all these years on the altar of things like ‘human mentors’ before we come for those top professors too? It’s not like most of them even want to be actually teaching in the first place.

A job the AI really should take, when will it happen?

Kevin Bryan: Today in AI diffusion frictions: in a big security line at YYZ waiting for a guy to do pattern recognition on bag scans. 100% sure this could be done instantaneously at better false positive and false negative rate with algo we could train this week. What year will govt switch?

I do note it is not quite as easy as a better error rate, because this is adversarial. You need your errors to be importantly unpredictable. If there is a way I can predictably fool the AI, that’s a dealbreaker for relying fully on the AI even if by default the AI is a lot better. You would then need a mixed strategy.

Rather than thinking in jobs, one can think in types of tasks.

Here is one intuition pump:

Alex Albert (Anthropic): Claude raises the waterline for competence. It handles 99% of general discrete tasks better than the average person – the kind of work that used to require basic professional training but not deep expertise.

This creates an interesting split: routine generalist work (basic coding, first-draft writing, common diagnoses) becomes commoditized, while both deep specialists AND high-level generalists (those who synthesize across domains) become more valuable.

LLMs compress the middle of the skill distribution. They automate what used to require modest expertise, leaving people to either specialize deeply in narrow fields or become meta-thinkers who connect insights across domains in ways AI can’t yet match.

We’re not just becoming a species of specialists – we’re bifurcating. Some go deep into niches, others rise above to see patterns LLMs currently miss. The comfortable middle ground seems to be disappearing.

Tobias Yergin: I can tell you right now that o3 connects seemingly disparate data points across myriad domains better than nearly every human on earth. It turns out this is my gift and I’ve used it to full effect as an innovator, strategist, and scenario planner at some of the world’s largest companies (look me up on LinkedIn).

It is the thing I do better than anyone I’ve met in person… and it is better at this than me. This is bad advice IMO.

Abhi: only partly true. the way things are trending, it looks like ai is gonna kill mediocrity.

the best people in any field get even better with the ai, and will always be able to squeeze out way more than any normal person. and thus, they will remain in high demand.

Tobias is making an interesting claim. While o3 can do the ‘draw disparate sources’ thing, it still hasn’t been doing the ‘make new connections and discoveries’ thing in a way that provides clear examples – hence Dwarkesh Patel and others continuing to ask about why LLMs haven’t made those unique new connections and discoveries yet.

Abhi is using ‘always’ where he shouldn’t. The ‘best people’ eventually lose out too in the same way that they did in chess or as calculators. There’s a step in between, they hang on longer, and ‘be the best human’ still can have value – again, see chess – but not in terms of the direct utility of the outputs.

What becomes valuable when AI gets increasingly capable is the ability to extract those capabilities from the AI, to know which outputs to extract and how to evaluate them, or to provide complements to AI outputs. Basic professional training for now can still be extremely valuable even if AI is now ‘doing your job for you,’ because that training lets you evaluate the AI outputs and know which ones to use for what task. One exciting twist is that this ‘basic professional training’ will also increasingly be available from the AI, or the AI will greatly accelerate such training. I’ve found that to be true essentially everywhere, and especially in coding.

Elysian Labs is hiring for building Auren, if you apply do let them know I should get that sweet referral bonus.

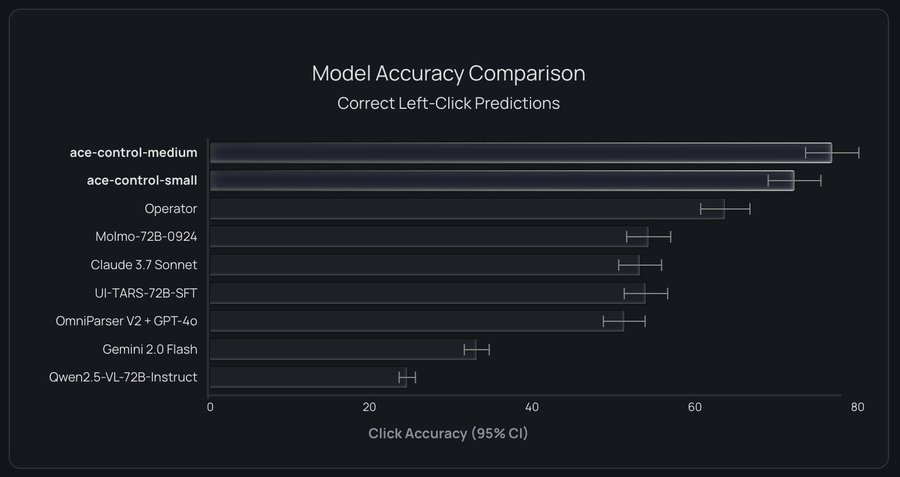

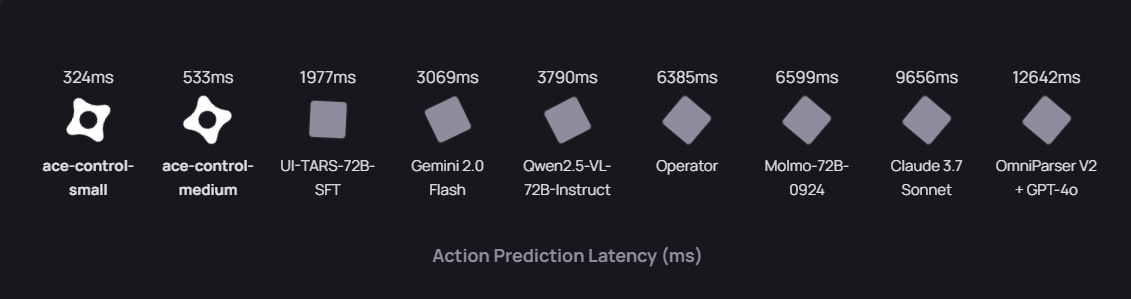

Introducing Ace, a real time computer autopilot.

Yohei: this thing is so fast. custom trained model for computer use.

Sherjil Ozair: Today I’m launching my new company @GeneralAgentsCo and our first product [in research preview, seeking Alpha testers.]

Introducing Ace: The First Realtime Computer Autopilot

Ace is not a chatbot. Ace performs tasks for you. On your computer. Using your mouse and keyboard. At superhuman speeds!

Ace can use all the tools on your computer. Ace accelerates your work, and helps you confidently use tools you’re still learning. Just ask Ace what you need, it gets it done.

Ace can optionally use frontier reasoning models for more complex tasks.

Ace outperforms other models on our evaluation suite of computer tasks which we are open sourcing here.

Ace is blazing fast! It’s 20x faster than competing agents, making it more practical for everyday use.

To learn and sign up, click here.

For many applications, speed kills.

It is still early, so I don’t have any feedback to report on whether it’s good or safe.

They don’t explain here what precautions are being taken with an agent that is using your own keyboard and mouse and ‘all the tools on your computer.’ The future is going to involve things like this, but how badly do you want to go first?

Ace isn’t trying to solve the general case so much as they are trying to solve enough specific cases they can string together? They are using behavioral cloning, not reinforcement learning.

Sherjil Ozair: A lot of people presume we use reinforcement learning to train Ace. The founding team has extensive RL background, but RL is not how we’ll get computer AGI.

The single best way we know how to create artificial intelligence is still large-scale behaviour cloning.

This also negates a lot of AGI x-risk concerns imo.

Typical safety-ist argument: RL will make agents blink past human-level performance in the blink of an eye

But: the current paradigm is divergence minimization wrt human intelligence. It converges to around human performance.

For the reasons described this makes me feel better about the whole enterprise. If you want to create a computer autopilot, 99%+ of what we do on computers is variations on the same set of actions. So if you want to make something useful to help users save time, it makes sense to directly copy those actions. No, this doesn’t scale as far, but that’s fine here and in some ways it’s even a feature.

I think of this less as ‘this is how we get computer AGI’ as ‘we don’t need computer AGI to build something highly useful.’ But Sherjil is claiming this can go quite a long way:

Sherjil Ozair: I can’t believe that we’ll soon have drop-in remote workers, indistinguishable from a human worker, and it will be trained purely on behavioral inputs/outputs. Total behaviorism victory!

The best thing about supervised learning is that you can clone any static system arbitrarily well. The downside is that supervised learning only works for static targets.

This is an AI koan and also career advice.

Also, Sherjil Ozair notes they do most of their hiring via Twitter DMs.

Gemini Pro 2.5 Model Card Watch continues. It is an increasingly egregious failure for them not to have published this. Stop pretending that labeling this ‘experimental’ means you don’t have to do this.

Peter Wildeford: LEAKED: my texts to the DeepMind team

Report is that OpenAI’s Twitter alternative will be called Yeet? So that posts can be called Yeets? Get it? Sigh.

A new paper suggests that RL-trained models are better at low k (e.g. pass@1) but that base models actually outperform them at high k (e.g. pass@256).

Tanishq Mathew Abraham: “RLVR enhances sampling efficiency, not reasoning capacity, while inadvertently shrinking the solution space.”

Gallabytes: this is true for base models vs the random init too. pass@1 is the thing that limits your ability to do deep reasoning chains.

Any given idea can already be generated by the base model. An infinite number of monkeys can write Shakespeare. In both cases, if you can’t find the right answer, it is not useful. A pass@256 is only good if you can do reasonable verification. For long reasoning chains you can’t do that. Discernment is a key part of intelligence, as is combining many steps. So it’s a fun result but I don’t think it matters?

Goodfire raises a $50 million series A for interpretability, shows a preview of its ‘universal neural programming platform’ Ember.

OpenAI in talks to buy Windsurf. There are many obvious synergies. The data is valuable, the vertical integration brings various efficiencies, and it’s smart to want to incorporate a proper IDE into OpenAI’s subscription offerings, combine memory and customization across modalities and so on.

Do you think this is going to be how all of this works? Do you want it to be?

Nat McAleese (OpenAI): in the future “democracy” will be:

-

everyone talks to the computer

-

the computer does the right thing

These guys are building it today.

Alfred Wahlforss: AI writes your code. Now it talks to your users.

We raised $27M from @Sequoia to build @ListenLabs.

Listen runs thousands of interviews to uncover what users want, why they churn, and what makes them convert.

Bonus question: Do you think that is democracy? That is will do what the users want?

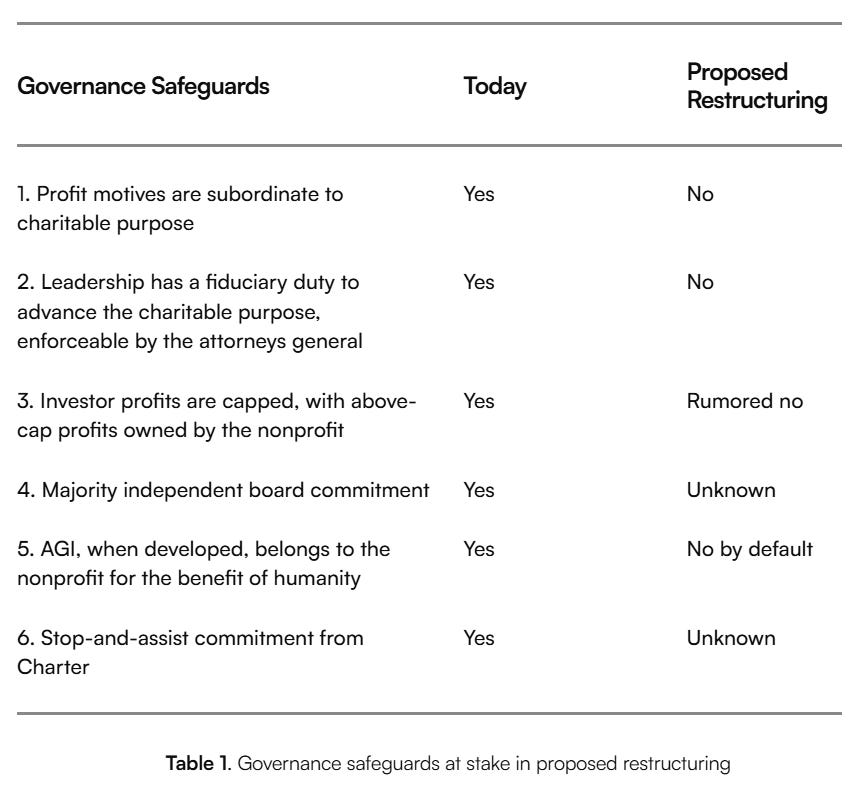

Lighthaven PR Department: non profit devoted to making sure agi benefits all of humanity announces new strategy of becoming a for profit with no obligation to benefit humanity

A new private letter to the two key Attorney Generals urges them to take steps to prevent OpenAI from converting to a for-profit, as it would wipe out the nonprofit’s charitable purpose. That purpose requires the nonprofit retain control of OpenAI. The letter argues convincingly against allowing the conversion.

They argue no sale price can compensate for loss of control. I would not go that far, one can always talk price, but right now the nonprofit is slated to not even get fair value for its profit interests, let alone compensation for its control rights. That’s why I call it the second biggest theft in human history. On top of that, the nonprofit is slated to pivot its mission to focus on a cross between ‘ordinary philanthropy’ and OpenAI’s marketing department, deploying OpenAI products to nonprofits. That’s a good thing to do on the margin, but it does not address AI’s existential dangers at all.

They argue that the conversion is insufficiently justified. They cite competitive advantage, and there is some truth there to be sure, but it has not been shown either that this is necessary to be competitive, or that the resulting version of OpenAI would then advance the nonprofit’s mission.

OpenAI might respond that a competitive advantage inherently advances its mission, but that argument is an implicit comparison of OpenAI and its competitors: that humanity would be better off if OpenAI builds AGI before competing companies. Based on OpenAI’s recent track record, this argument is unlikely to be convincing: ⁷¹

-

OpenAI’s testing processes have reportedly become “less thorough with insufficient time and resources dedicated to identifying and mitigating risks.”⁷²

-

It has rushed through safety testing to meet a product release schedule.⁷³

-

It reneged on its promise to dedicate 20% of its computing resources to the team tasked with ensuring AGI’s safety.⁷⁴

-

OpenAI and its leadership have publicly claimed to support AI regulation⁷⁵ while OpenAI privately lobbied against it.⁷⁶

-

Mr. Altman said that it might soon become important to reduce the global availability of computing resources⁷⁷ while privately attempting to arrange trillions of dollars in computing infrastructure buildout with U.S. adversaries.⁷⁸

-

OpenAI coerced departing employees into extraordinarily restrictive non-disparagement agreements.⁷⁹

The proposed plan of action is to demand answers to key questions about the proposed restructuring, and to protect the charitable trust and purpose by ensuring control is retained, including by actively pushing for board independence and fixing the composition of the board, since it appears to have been compromised by Altman in the wake of the events surrounding his firing.

I consider Attorney General action along similar lines to be the correct way to deal with this situation. Elon Musk is suing and may have standing, but he also might not and that is not the right venue or plaintiff. The proposed law to ban such conversions had to be scrapped because of potential collateral damage and the resulting political barriers, and was already dangerously close to being a Bill of Attainder which was why I did not endorse it. The Attorney Generals are the intended way to deal with this. They need to do their jobs.

Dwarkesh patel asks 6k words worth of mostly excellent questions about AI, here’s a Twitter thread. Recommended. I’m left with the same phenomenon I imagine my readers are faced with: There’s too many different ways one could respond and threads one could explore and it seems so overwhelming most people don’t respond at all. A worthy response would be many times the length of the original – it’s all questions, it’s super dense. Also important are what questions are missing.

So I won’t write a full response directly. Instead, I’ll be drawing from it elsewhere and going forward.

Things are escalating quickly.

Paul Graham: One of the questions I ask startups is how long it’s been possible to do what they’re doing. Ideally it has only been possible for a few years. A couple days ago I asked this during office hours, and the founders said “since December.” What’s possible now changes in months.

Colin Percival: How often do you get the answer “well, we don’t know yet if it *ispossible”?

Paul Graham: Rarely, but it’s exciting when I do.

Yet Sam Altman continues to try and spin that Nothing Ever Happens.

Sam Altman (CEO OpenAI): I think this is gonna be more like the renaissance than the industrial revolution.

That sounds nice but does not make any sense. What would generate that outcome?

The top AI companies are on different release cycles. One needs to not overreact:

Andrew Curran: The AI saga has followed story logic for the past two years. Every time a lab falls even slightly behind, people act as if it’s completely over for them. Out of the race!

Next chapter spoiler: it’s Dario Amodei – remember him – and he’s holding a magic sword named Claude 4.

Peter Wildeford: This is honestly how all of you sound:

Jan: DeepSeek is going to crush America

Feb: OpenAI Deep Research, they’re going to win

Also Feb: Claude 3.7… Anthropic is going to win

Mar: Gemini 2.5… Google was always going to dominate, I knew it

Now: o3… no one can beat OpenAI

It doesn’t even require that the new release actually be a superior model. Don’t forget that couple of days when Grok was super impressive and everyone was saying how fast it was improving, or the panic over Manus, or how everyone massively overreacted to DeepSeek’s r1. As always, not knocking it, DeepSeek cooked and r1 was great, a reaction was warranted, but r1 was still behind the curve and the narratives around it got completely warped and largely still are, in ways that would be completely different if we’d understood better or if r1 had happened two weeks later.

An argument that GPT-4.5 was exactly what you would expect from scaling laws, but GPT-4.5’s post training wasn’t as good as other models, so its performance is neither surprising nor a knock on further scaling. We have found more profit for now on other margins, but that will change, and then scaling will come back.

Helen Toner lays out the case for a broad audience that the key unknown in near term AI progress is reward specification. What areas beyond math and coding will allow automatically graded answers? How much can we use performance in automatically graded areas to get spillover into other areas?

Near Cyan: reminder of how far AGI goalposts have moved.

I know i’ve wavered a bit myself but I think any timeline outside of the range of 2023-2028 is absolutely insane and is primarily a consequence of 99.9999% of LLM users using them entirely wrong and with zero creativity, near-zero context, no dynamic prompting, and no integration.

source for the above text is from 2019 by the way!

Andrej Karpathy: I feel like the goalpost movement in my tl is in the reverse direction recently, with LLMs solving prompt puzzles and influencers hyperventilating about AGI. The original OpenAI definition is the one I’m sticking with, I’m not sure what people mean by the term anymore.

OpenAI: By AGI we mean a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work.

By the OpenAI definition we very clearly do not have AGI, even if we include only work on computers. It seems rather silly to claim otherwise. You can see how we might get there relatively soon. I can see how Near’s statement could be made (minus several 9s) about 2025-2030 as a range, and at least be a reasonable claim. But wow, to have your range include two years in the past seems rather nutty, even for relatively loose definitions.

Ethan Mollick calls o3 and Gemini 2.5 Pro ‘jagged AGI’ in that they have enough superhuman capabilities to result in real changes to how we work and live. By that definition, what about good old Google search? We basically agree on the practical question of what models at this level will do on their own, that they will change a ton of things but it will take time to diffuse.

BIS (the Bureau of Industry and Security), which is vital to enforcing the export controls, is such a no-brainer that even AI czar David Sacks supports it while advocating for slashing every other bureaucracy.

Given the stakes are everyone dies or humanity loses control, international cooperation seems like something we should be aiming for.

Miles Brundage and Grace Werner make the case that America First Meets Safety First, that the two are fully compatible and Trump is well positioned to make a deal (he loves deals!) with China to work together on catastrophic risks and avoid the threat of destabilizing the situation, while both sides continue to engage in robust competition.

They compare this to the extensive cooperation between the USA and USSR during the cold war to guard against escalation, and point out that China could push much harder on AI than it is currently pushing, if we back them into a corner. They present a multi-polar AI world as inevitable, so we’ll need to coordinate to deal with the risks involved, and ensure our commitments are verifiable, and that we’re much better off negotiating this now while we have the advantage.

We also have a paper investigating where this cooperation is most practical.

Yoshua Bengio: Rival nations or companies sometimes choose to cooperate because some areas are protected zones of mutual interest—reducing shared risks without giving competitors an edge.

Our paper in FAccT ’25: How geopolitical rivals can cooperate on AI safety research in ways that benefit all while protecting national interests.

Ben Bucknall: Cooperation on AI safety is necessary but also comes with potential risks. In our new paper, we identify technical AI safety areas that present comparatively lower security concerns, making them more suitable for international cooperation—even between geopolitical rivals.

They and many others have a new paper on which areas of technical AI safety allow for geopolitical rivals to cooperate.

Ben Bucknall: Historically, rival states have cooperated on strategic technologies for several key reasons: managing shared risks, exchanging safety protocols, enhancing stability, and pooling resources when development costs exceed what any single nation can bear alone.

Despite these potential benefits, cooperation on AI safety research may also come with security concerns, including: Accelerating global AI capabilities; Giving rivals disproportionate advantages; Exposing sensitive security information; Creating opportunities for harmful action.

We look at four areas of technical AI safety where cooperation has been proposed and assess the extent to which cooperation in each area may pose these risks. We find that protocols and verification may be particularly well-suited to international cooperation.

Nvidia continues to play what look like adversarial games against the American government. They at best are complying with the exact letter of what they are legally forced to do, and they are flaunting this position, while also probably turning a blind eye to smuggling.

Kristina Partsinevelos (April 16, responding to H20 export ban): Nvidia response: “The U.S. govt instructs American businesses on what they can sell and where – we follow the government’s directions to the letter” […] “if the government felt otherwise, it would instruct us.”

Thomas Barrabi: Nvidia boss Jensen Huang reportedly met with the founder of DeepSeek on Thursday during a surprise trip to Beijing – just one day after a House committee revealed a probe into whether the chip giant violated strict export rules by selling to China.