This Chinese company could become the country’s first to land a reusable rocket

From the outside, China’s Zhuque-3 rocket looks like a clone of SpaceX’s Falcon 9.

LandSpace’s Zhuque-3 rocket with its nine first stage engines. Credit: LandSpace

There’s a race in China among several companies vying to become the next to launch and land an orbital-class rocket, and the starting gun could go off as soon as tonight.

LandSpace, one of several maturing Chinese rocket startups, is about to launch the first flight of its medium-lift Zhuque-3 rocket. Liftoff could happen around 11 pm EST tonight (04: 00 UTC Wednesday), or noon local time at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern China.

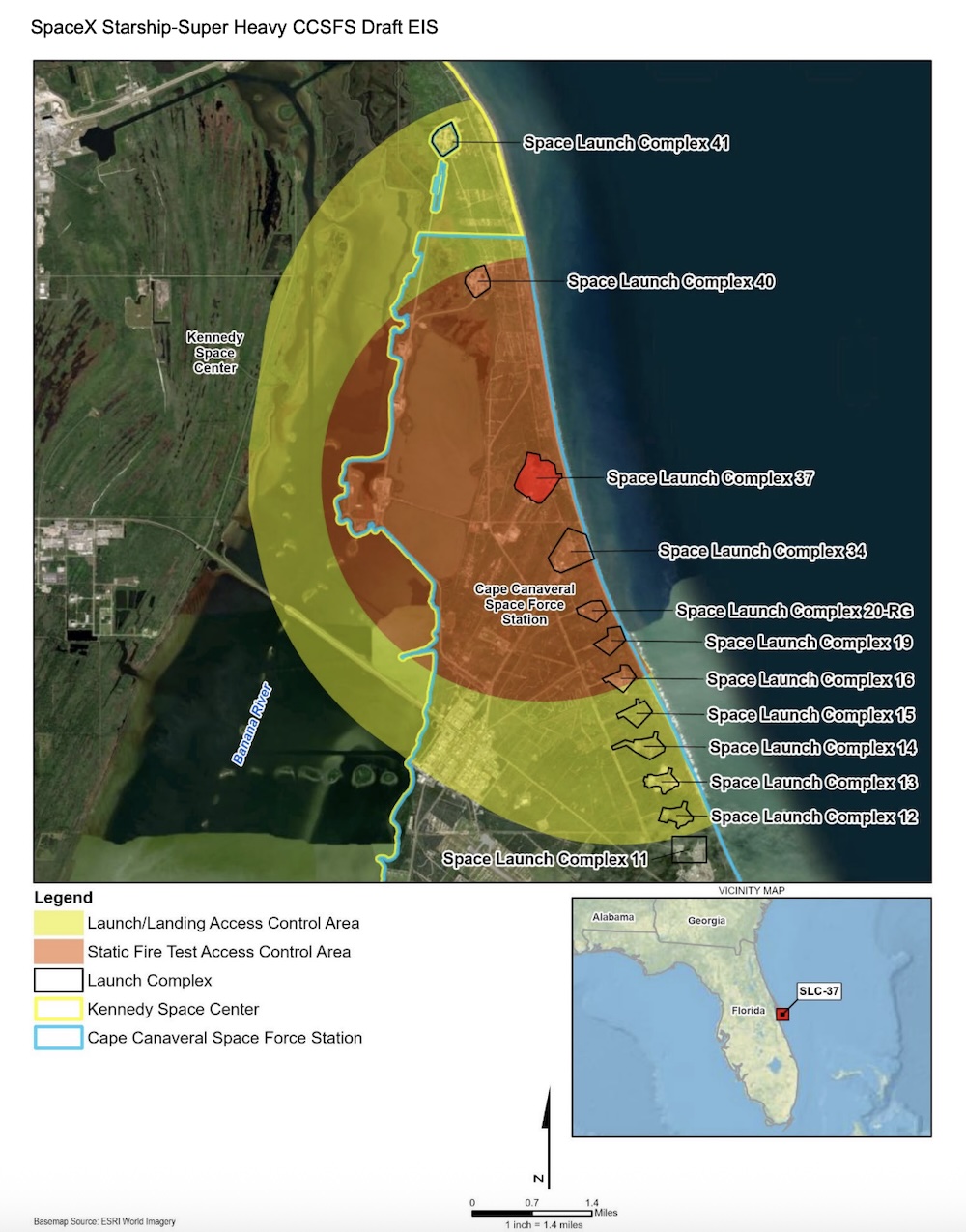

Airspace warning notices advising pilots to steer clear of the rocket’s flight path suggest LandSpace has a launch window of about two hours. When it lifts off, the Zhuque-3 (Vermillion Bird-3) rocket will become the largest commercial launch vehicle ever flown in China. What’s more, LandSpace will become the first Chinese launch provider to attempt a landing of its first stage booster, using the same tried-and-true return method pioneered by SpaceX and, more recently, Blue Origin in the United States.

Construction crews recently finished a landing pad in the remote Gobi Desert, some 240 miles (390 kilometers) southeast of the launch site at Jiuquan. Unlike US spaceports, the Jiuquan launch base is located in China’s interior, with rockets flying over land as they climb into space. When the Zhuque-3 booster finishes its job of sending the rocket toward orbit, it will follow an arcing trajectory toward the recovery zone, firing its engines to slow for landing about eight-and-a-half minutes after liftoff.

LandSpace’s reusable rocket test vehicle lifts off from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center for a high-altitude test flight on Wednesday, September 11, 2024. Credit: Landspace

A first step for China

At least, that’s what is supposed to happen. LandSpace officials have not made any public statements about the odds of a successful landing—or, for that matter, a successful launch. It took Blue Origin, a much larger enterprise than LandSpace backed by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, two tries to land its New Glenn booster on a floating barge after launching from Cape Canaveral, Florida. A decade ago, SpaceX achieved the first of its now more than 500 rocket landings after many more attempts.

LandSpace was established in 2015, soon after the Chinese government introduced space policy reforms, opening the door for private capital to begin funding startups in the satellite and launch industries. So far, the company has raised more than $400 million from venture capital firms and investment funds backed by the Chinese government.

With this money, LandSpace has developed its own liquid-fueled engines and a light-class launcher named Zhuque-2, which became the world’s first methane-burning launcher to reach orbit in 2023. LandSpace’s Zhuque-2 has logged four successful missions in six tries.

But the Beijing-based company’s broader goal has been the development of a larger, partially reusable rocket to meet China’s growing appetite for satellite services. LandSpace finds itself in a crowded field of competitors, with China’s legacy state-owned rocket developers and a slate of venture-backed startups also in the mix.

The first stage of the Zhuque-3 rocket underwent a test-firing of its nine engines in June. Credit: LandSpace

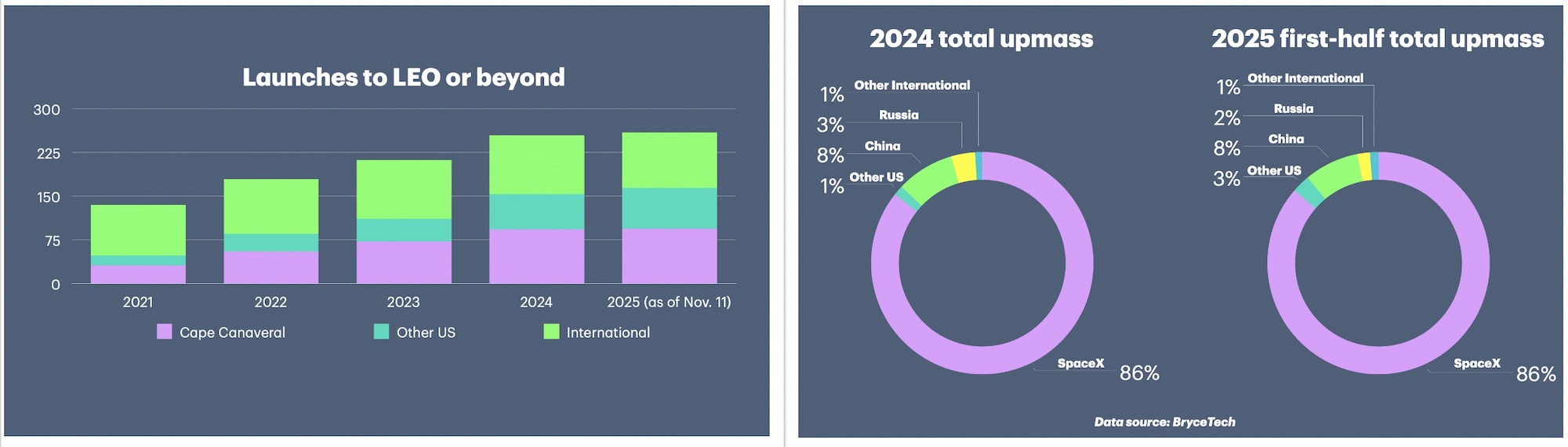

China needs reusable rockets to keep up with the US launch industry, dominated by SpaceX, which flies more often and hauls heavier cargo to orbit than all Chinese rockets combined. There are at least two Chinese megaconstellations now being deployed in low-Earth orbit, each with architectures requiring thousands of satellites to relay data and Internet signals around the world. Without scaling up satellite production and reusing rockets, China will have difficulty matching the capacities of SpaceX, Blue Origin, and other emerging US launch companies.

Just three months ago, US military officials identified China’s advancements in reusable rocketry as a key to unlocking the country’s ability to potentially threaten US assets in space. “I’m concerned about when the Chinese figure out how to do reusable lift that allows them to put more capability on orbit at a quicker cadence than currently exists,” said Brig. Gen. Brian Sidari, the Space Force’s deputy chief of space operations for intelligence, at a conference in September.

Without reusable rockets, China has turned to a wide variety of expendable boosters this year to launch less than half as often as the United States. China has made 77 orbital launch attempts so far this year, but no single rocket type has flown more than 13 times. In contrast, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 is responsible for 153 of 182 launches by US rockets.

That’s no Falcon 9

The Chinese companies that master reusable rocketry first will have an advantage in the Chinese launch industry. A handful of rockets appear to be poised to take this advantage, beginning with LandSpace’s Zhuque-3.

In its first iteration, the Zhuque-3 rocket will be capable of placing a payload of up to 17,600 pounds (8 metric tons) into low-Earth orbit after accounting for the fuel reserves required for booster recovery. The entire rocket stands about 216 feet (65.9 meters) tall.

The first stage has nine TQ-12A engines consuming methane and liquid oxygen, producing more than 1.6 million pounds of thrust at full throttle. The second stage is powered by a single methane-fueled TQ-15A engine with about 200,000 pounds of thrust. These are the same engines LandSpace has successfully flown on the smaller Zhuque-2 rocket.

LandSpace eventually plans to debut an upgraded Zhuque-3 carrying more propellant and using more powerful engines, raising its payload capacity to more than 40,000 pounds (18.3 metric tons) in reusable mode, or a few tons more with an expendable booster.

From the outside, LandSpace’s new rocket looks a lot like the vehicle it is trying to emulate: SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Like the Falcon 9, the Zhuque-3 booster’s nine-engine design also features four deployable landing legs and grid fins to help steer the rocket toward landing.

But LandSpace also incorporates elements from SpaceX’s much heavier Starship rocket. The primary structure of the Zhuque-3 is made of stainless steel, and its engines burn methane fuel, not kerosene like the Falcon 9.

The Zhuque-3 booster’s landing legs are visible here, folded up against the rocket’s stainless steel fuselage. Credit: LandSpace

In preparation for the debut of the Zhuque-3, LandSpace engineers built a prototype rocket for launch and landing demonstrations. The testbed aced a flight to 10 kilometers, or about 33,000 feet, in September 2024 and descended to a pinpoint vertical landing, validating the rocket’s guidance algorithms and engine restart capability.

The first of many

Another reusable booster is undergoing preflight preparations not far from LandSpace’s launch site at Jiuquan. This rocket, called the Long March 12A, comes from one of China’s established government-owned rocket firms. It could fly before the end of this year, but officials haven’t publicized a schedule.

The Long March 12A has comparable performance to LandSpace’s Zhuque-3, and it will also use a cluster of methane-fueled engines. Its developer, the Shanghai Institute of Spaceflight Technology, will attempt to land the Long March 12A booster on the first flight.

Several other companies working on reusable rockets appear to be in an advanced stage of development.

One of them, Space Pioneer, might have been first to flight with its new Tianlong-3 rocket if not for the thorny problem of an accidental launch during a booster test-firing last year. Space Pioneer eventually completed a successful static fire in September of this year, and the company recently released a photo showing its rocket on the launch pad.

Other Chinese companies with a chance of soon flying their new reusable boosters include CAS Space, which recently shipped its first Kinetica-2 rocket to Jiuquan for launch preps. Galactic Energy completed test-firings of the second stage and first stage for its Pallas-1 rocket in September and November.

Another startup, i-Space, is developing a partially reusable rocket called the Hyperbola-3 that could debut next year from China’s southern spaceport on Hainan Island. Officials from i-Space unveiled an ocean-going drone ship for rocket landings earlier this year. Deep Blue Aerospace is also working on vertical landing technology for its Nebula-1 rocket, having conducted a dramatic high-altitude test flight last year.

These rockets all fall in the small- to medium-class performance range. It’s unclear whether any of these companies will try to land their boosters on their first flights—like the Zhuque-3 and Long March 12A—but all have roadmaps to reusability.

China’s largest rocket developer, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, is not as close to fielding a reusable launcher. But the academy has far greater ambitions, with a pair of super-heavy rockets in its future. The first will be the Long March 10, designed to fly with reusable boosters while launching China’s next-generation crew spacecraft on missions to the Moon. Later, perhaps in the 2030s, China could debut the fully reusable Long March 9 rocket similar in scale to SpaceX’s Starship.

This Chinese company could become the country’s first to land a reusable rocket Read More »