Rocket Report: A new super-heavy launch site in California; 2025 year in review

SpaceX opened its 2026 launch campaign with a mission for the Italian government.

A Chinese Long March 7 rocket carrying a cargo ship for China’s Tiangong space station soars into orbit from the Wenchang Space Launch Site on July 15, 2025. Credit: Liu Guoxing/VCG via Getty Images

Welcome to Edition 8.24 of the Rocket Report! We’re back from a restorative holiday, and there’s a great deal Eric and I look forward to covering in 2026. You can get a taste of what we’re expecting this year in this feature. Other storylines are also worth watching this year that didn’t make the Top 20. Will SpaceX’s Starship begin launching Starlink satellites? Will United Launch Alliance finally get its Vulcan rocket flying at a higher cadence? Will Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket be certified by the US Space Force? I’m looking forward to learning the answers to these questions, and more. As for what has already happened in 2026, it has been a slow start on the world’s launch pads, with only a pair of SpaceX missions completed in the first week of the year. Only? Two launches in one week by any company would have been remarkable just a few years ago.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

New launch records set in 2025. The number of orbital launch attempts worldwide last year surpassed the record 2024 flight rate by 25 percent, with SpaceX and China accounting for the bulk of the launch activity, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. Including near-orbital flight tests of SpaceX’s Starship-Super Heavy launch system, the number of orbital launch attempts worldwide reached 329 last year, an annual analysis of global launch and satellite activity by Jonathan’s Space Report shows. Of those 329 attempts, 321 reached orbit or marginal orbits. In addition to five Starship-Super Heavy launches, SpaceX launched 165 Falcon 9 rockets in 2025, surpassing its 2024 record of 134 Falcon 9 and two Falcon Heavy flights. No Falcon Heavy rockets flew in 2025. US providers, including Rocket Lab Electron orbital flights from its New Zealand spaceport, added another 30 orbital launches to the 2025 tally, solidifying the US as the world leader in space launch.

International launches… China, which attempted 92 orbital launches in 2025, is second, followed by Russia, with 17 launches last year, and Europe with eight. Rounding out the 2025 orbital launch manifest were five orbital launch attempts from India, four from Japan, two from South Korea, and one each from Israel, Iran, and Australia, the analysis shows. The global launch tally has been on an upward trend since 2019, but the numbers may plateau this year. SpaceX expects to launch about the same number of Falcon 9 rockets this year as it did last year as the company prepares to ramp up the pace of Starship flights.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

South Korean startup suffers launch failure. The first commercial rocket launched at Brazil’s Alcantara Space Center crashed soon after liftoff on December 22, dealing a blow to Brazilian aerospace ambitions and the South Korean satellite launch company Innospace, Reuters reports. The rocket began its vertical trajectory as planned after liftoff but fell to the ground after something went wrong 30 seconds into its flight, according to Innospace, the South Korean startup that developed the launch vehicle. The craft crashed within a pre-designated safety zone and did not harm anyone, officials said.

An unsurprising result... This was the first flight of Innospace’s nano-launcher, named Hanbit-Nano. The rocket was loaded with eight small payloads, including five deployable satellites, heading for low-Earth orbit. But rocket debuts don’t have a good track record, and Innospace’s rocket made it a bit farther than some new launch vehicles do. The rocket is designed to place up to 200 pounds (90 kilograms) of payload mass into Sun-synchronous orbit. It has a unique design, with hybrid engines consuming a mix of paraffin as the fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer. Innospace said it intends to launch a second test flight in 2026. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Take two for Germany’s Isar Aerospace. Isar Aerospace is gearing up for a second launch attempt of its light-class Spectrum rocket after completing 30-second integrated static test firings for both stages late last year, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. The endeavor would be the first orbital launch for Spectrum and an effort at a clean mission after a March 30 flight ended in failure because a vent valve inadvertently opened soon after liftoff, causing a loss of control. “Rapid iteration is how you win in this domain. Being back on the pad less than nine months after our first test flight is proof that we can operate at the speed the world now demands,” said Daniel Metzler, co-founder and CEO of Isar Aerospace.

No earlier than… Airspace and maritime warning notices around the Spectrum rocket’s launch site in northern Norway suggest Isar Aerospace is targeting launch no earlier than January 17. Based near Munich, Isar Aerospace is Europe’s leading launch startup. Not only has Isar beat its competitors to the launch pad, the company has raised far more money than other European rocket firms. After its most recent fundraising round in June, Isar has raised more than 550 million euros ($640 million) from venture capital investors and government-backed funds. Now, Isar just needs to reach orbit.

A step forward for Canada’s launch ambitions. The Atlantic Spaceport Complex—a new launch facility being developed by the aerospace company NordSpace on the southern coast of Newfoundland—has won an important regulatory approval, NASASpaceflight.com reports. The provincial government of Newfoundland and Labrador “released” the spaceport from the environmental assessment process. “At this stage, the spaceport no longer requires further environmental assessment,” NordSpace said in a statement. “This release represents the single most significant regulatory milestone for NordSpace’s spaceport development to date, clearing the path for rapid execution of Canada’s first purpose-built, sovereign orbital launch complex designed and operated by an end-to-end launch services provider.”

Now, about that rocket... NordSpace began construction of the Atlantic Spaceport Complex last year and planned to launch its first suborbital rocket from the spaceport last August. But bad weather and technical problems kept NordSpace’s Taiga rocket grounded, and then the company had to wait for the Canadian government to reissue a launch license. NordSpace said it most recently delayed the suborbital launch until March in order to “continue our focus on advancing our orbital-scale technologies.” NordSpace is one of the companies likely to participate in a challenge sponsored by the Canadian government, which is committing 105 million Canadian dollars ($75 million) to develop a sovereign orbital launch capability. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

H3 rocket falters on the way to orbit. A faulty payload fairing may have doomed Japan’s latest H3 rocket mission, with the Japanese space agency now investigating if the shield separated abnormally and crippled the vehicle in flight after lifting off on December 21, the Asahi Shimbun reports. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency officials told a science ministry panel on December 23 they suspect an abnormal separation of the rocket’s payload fairing—a protective nose cone shield—caused a critical drop in pressure in the second-stage engine’s hydrogen tank. The second-stage engine lost thrust as it climbed into space, then failed to restart for a critical burn to boost Japan’s Michibiki 5 navigation satellite into a high-altitude orbit.

Growing pains… The H3 rocket is Japan’s flagship launch vehicle, having replaced the country’s H-IIA rocket after its retirement last year. The December launch was the seventh flight of an H3 rocket, and its second failure. While engineers home in on the rocket’s suspect payload fairing, several H3 launches planned for this year now face delays. Japanese officials already announced that the next H3 flight will be delayed from February. Japan’s space agency plans to launch a robotic mission to Mars on an H3 rocket in October. While there’s still time for officials to investigate and fix the issues that caused last month’s launch failure, the incident adds a question mark to the schedule for the Mars launch. (submitted by tsunam and EllPeaTea)

SpaceX opens 2026 with launch for Italy. SpaceX rang in the new year with a Falcon 9 rocket launch on January 2 from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, Spaceflight Now reports. The payload was Italy’s Cosmo-SkyMed Second Generation Flight Model 3 (CSG-FM3) satellite, a radar surveillance satellite for dual civilian and military use. The Cosmo-SkyMed mission was the first Falcon 9 rocket flight in 16 days, the longest stretch without a SpaceX orbital launch in four years.

Poached from Europe… The CSG-FM3 satellite is the third of four second-generation Cosmo-SkyMed radar satellites ordered by the Italian government. The second and third satellites have now launched on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets instead of their initial ride: Europe’s Vega C launcher. Italy switched the satellites to SpaceX after delays in making the Vega C rocket operational and Europe’s loss of access to Russian Soyuz rockets in the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine. The rocket swap became a regular occurrence for European satellites in the last few years as Europe’s indigenous launch program encountered repeated delays.

Rocket deploys heaviest satellite ever launched from India. An Indian LVM3 rocket launched AST SpaceMobile’s next-generation direct-to-device BlueBird satellite December 23, kicking off the rollout of dozens of spacecraft built around the largest commercial communications antenna ever deployed in low-Earth orbit, Space News reports. At 13,450 pounds (6.1 metric tons), the BlueBird 6 satellite was the heaviest spacecraft ever launched on an Indian rocket. The LVM3 rocket released BlueBird 6 into an orbit approximately 323 miles (520 kilometers) above the Earth.

The pressure is on… BlueBird 6 is the first of AST SpaceMobile’s Block 2 satellites designed to beam Internet signals directly to smartphones. The Texas-based company is competing with SpaceX’s Starlink network in the same direct-to-cell market. Starlink has an early lead in the direct-to-device business, but AST SpaceMobile says it plans to launch between 45 and 60 satellites by the end of this year. AST’s BlueBird satellites are significantly larger than SpaceX’s Starlink platforms, with antennas unfurling in space to cover an area of 2,400 square feet (223 square meters). The competition between SpaceX and AST SpaceMobile has led to a race for spectrum access and partnerships with cell service providers.

Ars’ annual power rankings of US rocket companies. There’s been some movement near the top of our annual power rankings. It was not difficult to select the first-place company on this list. As it has every year in our rankings, SpaceX holds the top spot. Blue Origin was the biggest mover on the list, leaping from No. 4 on the list to No. 2. It was a breakthrough year for Jeff Bezos’ space company, finally shaking the notion that it was a company full of promise that could not quite deliver. Blue Origin delivered big time in 2025. On the very first launch of the massive New Glenn rocket in January, Blue Origin successfully sent a test payload into orbit. Although a landing attempt failed after New Glenn’s engines failed to re-light, it was a remarkable success. Then, in November, New Glenn sent a pair of small spacecraft on their way to Mars. This successful launch was followed by a breathtaking and inspiring landing of the rocket’s first stage on a barge.

Where’s ULA?… Rocket Lab came in at No. 3. The company had an excellent year, garnering its highest total of Electron launches and having complete mission success. Rocket Lab has now gone more than three dozen launches without a failure. Rocket Lab also continued to make progress on its medium-lift Neutron vehicle, although its debut was ultimately delayed to mid-2026, at least. United Launch Alliance slipped from No. 2 to No. 4 after launching its new Vulcan rocket just once last year, well short of the company’s goal of flying up to 10 Vulcan missions.

Rocketdyne changes hands again. If you are a student of space history or tracked the space industry before billionaires and venture capital changed it forever, you probably know the name Rocketdyne. A half-century ago, Rocketdyne manufactured almost all of the large liquid-fueled rocket engines in the United States. The Saturn V rocket that boosted astronauts toward the Moon relied on powerful engines developed by Rocketdyne, as did the Space Shuttle, the Atlas, Thor, and Delta rockets, and the US military’s earliest ballistic missiles. But Rocketdyne has lost its luster in the 21st century as it struggled to stay relevant in the emerging commercial launch industry. Now, the engine-builder is undergoing its fourth ownership change in 20 years. AE Industrial Partners, a private equity firm, announced it will purchase a controlling stake in Rocketdyne from L3Harris after less than three years of ownership, Ars reports.

Splitting up… Rocketdyne’s RS-25 engine, used on NASA’s Space Launch System rocket, is not part of the deal with AE Industrial. It will remain under the exclusive ownership of L3Harris. Rocketdyne’s work on solid-fueled propulsion, ballistic missile interceptors, tactical missiles, and other military munitions will also remain under L3Harris control. The split of the company’s space and defense segments will allow L3Harris to concentrate on Pentagon programs, the company said. So, what is AE Industrial getting in its deal with L3Harris? Aside from the Rocketdyne name, the private equity firm will have a majority stake in the production of the liquid-fueled RL10 upper-stage engine used on United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket. AE Industrial’s Rocketdyne will also continue the legacy company’s work in nuclear propulsion, electric propulsion, and smaller in-space maneuvering thrusters used on satellites.

Tory Bruno has a new employer. Jeff Bezos-founded Blue Origin said on December 26 that it has hired Tory Bruno, the longtime CEO of United Launch Alliance, as president of its newly formed national security-focused unit, Reuters reports. Bruno will head the National Security Group and report to Blue Origin CEO Dave Limp, the company said in a social media post, underscoring its push to expand in US defense and intelligence launch markets. The hire brings one of the US launch industry’s most experienced executives to Blue Origin as the company works to challenge the dominance of SpaceX and win a larger share of lucrative US military and intelligence launch contracts.

11 years at ULA… The move comes days after Bruno stepped down as CEO of ULA, the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture that has long dominated US national security space launches alongside Elon Musk’s SpaceX. In 11 years at ULA, Bruno oversaw the development of the Vulcan rocket, the company’s next-generation launch vehicle designed to replace its Atlas V and Delta IV rockets and secure future Pentagon contracts. (submitted by r0twhylr)

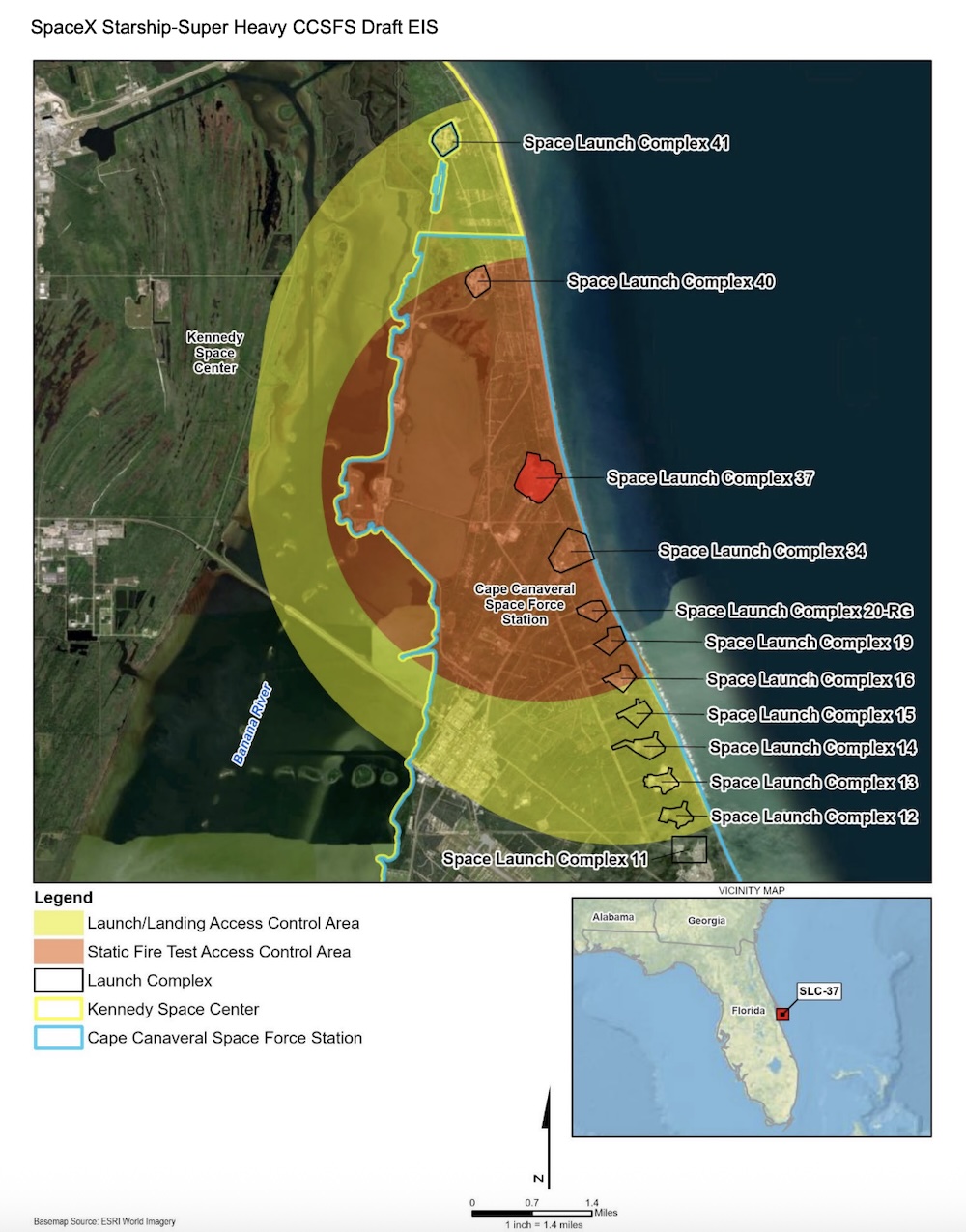

A California spaceport has room to grow. A new orbital launch site is up for grabs at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, Spaceflight Now reports. The Department of the Air Force published a request for information from launch providers to determine the level of interest in what would become the southernmost launch complex on the Western Range. The location, which will be designated as Space Launch Complex-14 or SLC-14, is being set aside for orbital rockets in a heavy or super-heavy vertical launch class. One of the requirements listed in the RFI includes what the government calls the “highest technical maturity.” It states that for the bid from a launch provider to be taken seriously, it needs to prove that it can begin operations within approximately five years of receiving a lease for the property.

Who’s in contention?… Multiple US launch providers have rockets in the heavy to super-heavy classification either currently launching or in development. Given all the requirements and the state of play on the orbital launch front, one of the contenders would likely be SpaceX’s Starship-Super Heavy rocket. The company is slated to launch the latest iteration of the rocket, dubbed Version 3, sometime in early 2026. Blue Origin is another likely contender for the prospective launch site. Blue Origin currently has an undeveloped space at Vandenberg’s SLC-9 for its New Glenn rocket. But the company unveiled plans in November for a new super-heavy lift version called New Glenn 9×4. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Next three launches

Jan. 9: Falcon 9 | Starlink 6-96 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 18: 05 UTC

Jan. 11: Falcon 9 | Twilight Mission | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 13: 19 UTC

Jan. 11: Falcon 9 | Starlink 6-97 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 18: 08 UTC

Rocket Report: A new super-heavy launch site in California; 2025 year in review Read More »