Rocket Report: SpaceX to make its own propellant; China’s largest launch pad

United Launch Alliance begins stacking its third Vulcan rocket for the second time.

Visitors walk by models of a Long March 10 rocket, lunar lander, and crew spacecraft during an exhibition on February 24, 2023 in Beijing, China. Credit: Hou Yu/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

Welcome to Edition 8.02 of the Rocket Report! It’s worth taking a moment to recognize an important anniversary in the history of human spaceflight next week. Fifty years ago, on July 15, 1975, NASA launched a three-man crew on an Apollo spacecraft from Florida and two Russian cosmonauts took off from Kazakhstan, on course to link up in low-Earth orbit two days later. This was the first joint US-Russian human spaceflight mission, laying the foundation for a strained but enduring partnership on the International Space Station. Operations on the ISS are due to wind down in 2030, and the two nations have no serious prospects to continue any partnership in space after decommissioning the station.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

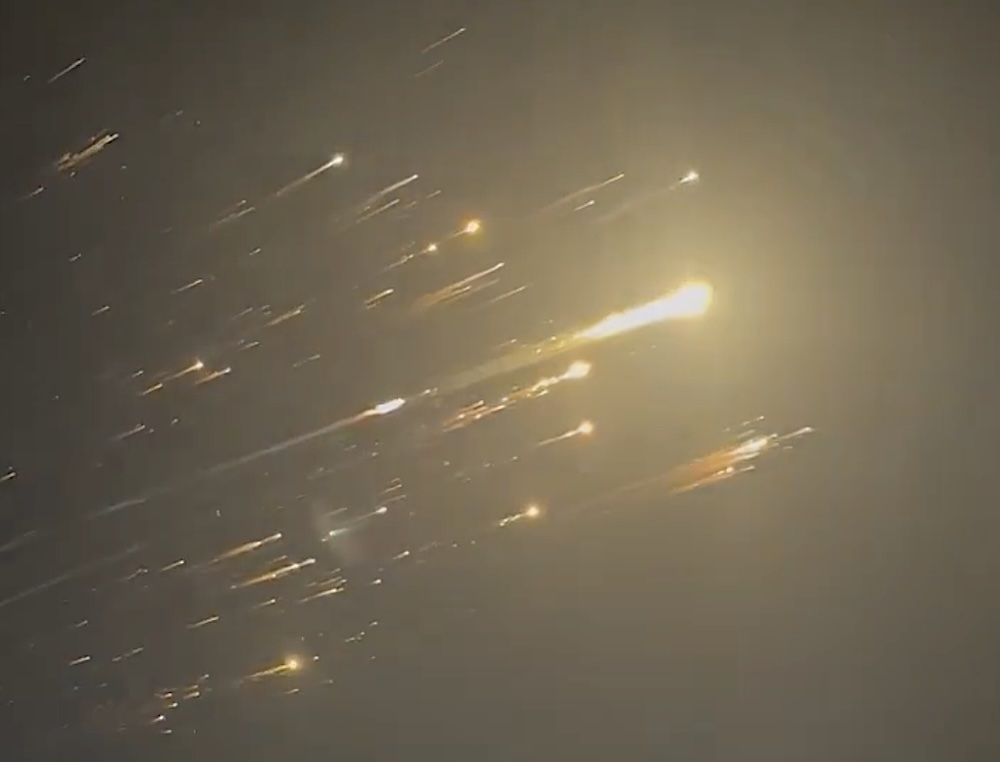

Sizing up Europe’s launch challengers. The European Space Agency has selected five launch startups to become eligible for up to 169 million euros ($198 million) in funding to develop alternatives to Arianespace, the continent’s incumbent launch service provider, Ars reports. The five small launch companies ESA selected are Isar Aerospace, MaiaSpace, Rocket Factory Augsburg, PLD Space, and Orbex. Only one of these companies, Isar Aerospace, has attempted to launch a rocket into orbit. Isar’s Spectrum rocket failed moments after liftoff from Norway on a test flight in March. None of these companies is guaranteed an ESA contract or funding. Over the next several months, ESA and the five launch companies will negotiate with European governments for funding leading up to ESA’s ministerial council meeting in November, when ESA member states will set the agency’s budget for at least the next two years. Only then will ESA be ready to sign binding agreements.

Let’s rank ’em … Ars Technica’s space reporters ranked the five selectees for the European Launcher Challenge in order from most likely to least likely to reach orbit. We put Munich-based Isar Aerospace, the most well-funded of the group, at the top of the list after attempting its first orbital launch earlier this year. Paris-based MaiaSpace, backed by ArianeGroup, comes in second, with plans for a partially reusable rocket. Rocket Factory Augsburg, another Germany company, is in third place after getting close to a launch attempt last year before its first rocket blew up on a test stand. Spanish startup PLD Space is fourth, and Britain’s Orbex rounds out the list. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Japan’s Interstellar Technologies rakes in more cash. Interstellar Technologies raised 8.9 billion yen ($61.8 million) to boost development of its Zero rocket and research and development of satellite systems, Space News reports. The money comes from Japanese financial institutions, venture capital funds, and debt financing. Interstellar previously received funding through agreements with the Japanese government and Toyota, which Interstellar says will add expertise to scale manufacturing of the Zero rocket for “high-frequency, cost-effective launches.” The methane-fueled Zero rocket is designed to deploy a payload of up to 1 metric ton (2,200 pounds) into low-Earth orbit. The unfortunate news from Interstellar’s fundraising announcement is that the company has pushed back the debut flight of the Zero rocket until 2027.

Straight up … Interstellar has aspirations beyond launch vehicles. The company is also developing a satellite communications business, and some of the money raised in the latest investment round will go toward this segment of the company. Interstellar is open about comparing its ambition to that of SpaceX. “On the satellite side, Interstellar is developing communications satellites that benefit from the company’s own launch capabilities,” the company said in a statement. “Backed by Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and JAXA’s Space Strategy Fund, the company is building a vertically integrated model, similar to SpaceX’s approach with Starlink.”

Korean startup completes second-stage qual testing. South Korean launch services company Innospace says it has taken another step toward the inaugural launch of its Hanbit-Nano rocket by the year’s end with the qualification of the second stage, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. The second stage uses an in-house-developed 34-kilonewton (7,643-pound-thrust) liquid methane engine. Innospace says the engine achieved a combustion time of 300 seconds, maintaining stability of the fuel and oxidizer supply system, structural integrity, and the launch vehicle integrated control system.

A true micro-launcher … Innospace’s rocket is modest in size and capacity, even among its cohorts in the small launch market. The Hanbit-Nano rocket is designed to launch approximately 200 pounds (90 kilograms) of payload into Sun-synchronous orbit. “With the success of this second stage engine certification test, we have completed the development of the upper stage of the Hanbit-Nano launch vehicle,” said Kim Soo-jong, CEO of Innospace. “This is a very symbolic and meaningful technological achievement that demonstrates the technological prowess and test operation capabilities that Innospace has accumulated over a long period of time, while also showing that we have entered the final stage for commercial launch. Currently, all executives and staff are doing their best to successfully complete the first stage certification test, which is the final gateway for launch, and we will make every effort to prepare for a smooth commercial launch in the second half of the year.”

Two companies forge unlikely alliance in Dubai. Two German entrepreneurs have joined forces with a team of Russian expats steeped in space history to design a rocket using computational AI models, Payload reports. The “strategic partnership” is between LEAP 71, an AI-enabled design startup, and Aspire Space, a company founded by the son of a Soviet engineer who was in charge of launching Zenit rockets from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in the 1980s. The companies will base their operations in Dubai. The unlikely pairing aims to develop a new large reusable launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 15 metric tons to low-Earth orbit. Aspire Space is a particularly interesting company if you’re a space history enthusiast. Apart from the connections of Aspire’s founder to Soviet space history, Aspire’s chief technology officer, Sergey Sopov, started his career at Baikonur working on the Energia heavy-lift rocket and Buran space shuttle, before becoming an executive at Sea Launch later in his career.

Trust the computer … It’s easy to be skeptical about this project, but it has attracted an interesting group of people. LEAP 71 has just two employees—its two German co-founders—but boasts lofty ambitions and calls itself a “pioneer in AI-driven engineering.” As part of the agreement with Aspire Space, LEAP 71 will use a proprietary software program called Noyron to design the entire propulsion stack for Aspire’s rockets. The company says its AI-enabled design approach for Aspire’s 450,000-pound-thrust engine will cut in half the time it took other rocket companies to begin test-firing a new engine of similar size. Rudenko forecasts Aspire’s entire project, including a launcher, reusable spacecraft, and ground infrastructure to support it all, will cost more than $1 billion. So far, the project is self-funded, Rudenko told Payload. (submitted by Lin Kayser)

Russia launches ISS resupply freighter. A Russian Progress supply ship launched July 3 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan atop a Soyuz-2.1a rocket, NASASpaceflight reports. Packed with 5,787 pounds (2,625 kilograms) of cargo and fuel, the Progress MS-31 spacecraft glided to an automated docking at the International Space Station two days later. The Russian cosmonauts living aboard the ISS will unpack the supplies carried inside the Progress craft’s pressurized compartment. This was the eighth orbital launch of the year by a Russian rocket, continuing a downward trend in launch activity for the Russian space program in recent years.

Celebrating a golden anniversary … The Soyuz rocket that launched Progress MS-31 was painted an unusual blue and white scheme, as it was originally intended for a commercial launch that was likely canceled after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It also sported a logo commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo-Soyuz mission in July 1975.

Chinese rocket moves closer to first launch. Chinese commercial launch firm Orienspace is aiming for a late 2025 debut of its Gravity-2 rocket following a recent first-stage engine hot fire test, Space News reports. The “three-in-one” hot fire test verified the performance of the Gravity-2 rocket’s first stage engine, servo mechanisms, and valves that regulate the flow of propellants into the engine, according to a press release from Orienspace. The Gravity-2 rocket’s recoverable and reusable first stage will be powered by nine of these kerosene-fueled engines. The recent hot fire test “lays a solid foundation” for future tests leading up to the Gravity-2’s inaugural flight.

Extra medium … Orienspace’s first rocket, the solid-fueled Gravity-1, completed its first successful flight last year to place multiple small satellites into orbit. Gravity-2 is a much larger vehicle, standing 230 feet (70 meters) tall, the same height as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Orienspace’s new rocket will fly in a core-only configuration or with the assistance of two solid rocket boosters. An infographic released by Orienspace in conjunction with the recent engine hot fire test indicates the Gravity-2 rocket will be capable of hauling up to 21.5 metric tons (47,400 pounds) of cargo into low-Earth orbit, placing its performance near the upper limit of medium-lift launchers.

Senator calls out Texas for trying to steal space shuttle. A political effort to remove space shuttle Discovery from the Smithsonian and place it on display in Texas encountered some pushback on Thursday, as a US senator questioned the expense of carrying out what he described as a theft, Ars reports. “This is not a transfer. It’s a heist,” said Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) during a budget markup hearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee. “A heist by Texas because they lost a competition 12 years ago.” In April, Republican Sens. John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, both representing Texas, introduced the “Bring the Space Shuttle Home Act” that called for Discovery to be relocated from the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia and displayed at Space Center Houston. They then inserted an $85 million provision for the shuttle relocation into the Senate version of the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which, to comply with Senate rules, was more vaguely worded but was meant to achieve the same goal. That bill was enacted on July 4, when President Donald Trump signed it into law.

Dollar signs … As ridiculous as it is to imagine spending $85 million on moving a space shuttle from one museum to another, it’ll actually cost a lot more to do it safely. Citing research by NASA and the Smithsonian, Durbin said that the total was closer to $305 million and that did not include the estimated $178 million needed to build a facility to house and display Discovery once in Houston. Furthermore, it was unclear if Congress even has the right to remove an artifact, let alone a space shuttle, from the Smithsonian’s collection. The Washington, DC, institution, which serves as a trust instrumentality of the US, maintains that it owns Discovery. The paperwork signed by NASA in 2012 transferred “all rights, interest, title, and ownership” for the spacecraft to the Smithsonian. “This will be the first time ever in the history of the Smithsonian someone has taken one of their displays and forcibly taken possession of it. What are we doing here? They don’t have the right in Texas to claim this,” said Durbin.

Starbase keeps getting bigger. Cameron County, Texas, has given SpaceX the green light to build an air separator facility, which will be located less than 300 feet from the region’s sand dunes, frustrating locals concerned about the impact on vegetation and wildlife, the Texas Tribune reports. The commissioners voted 3–1 to give Elon Musk’s rocket company a beachfront construction certificate and dune protection permit, allowing the company to build a facility to produce gases needed for Starship launches. The factory will separate air into nitrogen and oxygen. SpaceX uses liquid oxygen as a propellant and liquid nitrogen for testing and operations.

Saving the roads … By having the facility on site, SpaceX hopes to make the delivery of those gases more efficient by eliminating the need to have dozens of trucks deliver them from Brownsville. The company says they need more than 200 trucks of liquid nitrogen and oxygen delivered for each launch, a SpaceX engineer told the county during a meeting last week. With their application, SpaceX submitted a plan to mitigate expected negative effects on 865 square feet of dune vegetation and 20 cubic yards of dunes, as well as compensate for expected permanent impacts to 7,735 square feet of dune vegetation and 465 cubic yards of dunes. While the project will be built on property owned by SpaceX, the county holds the authority to manage the construction that affects Boca Chica’s dunes.

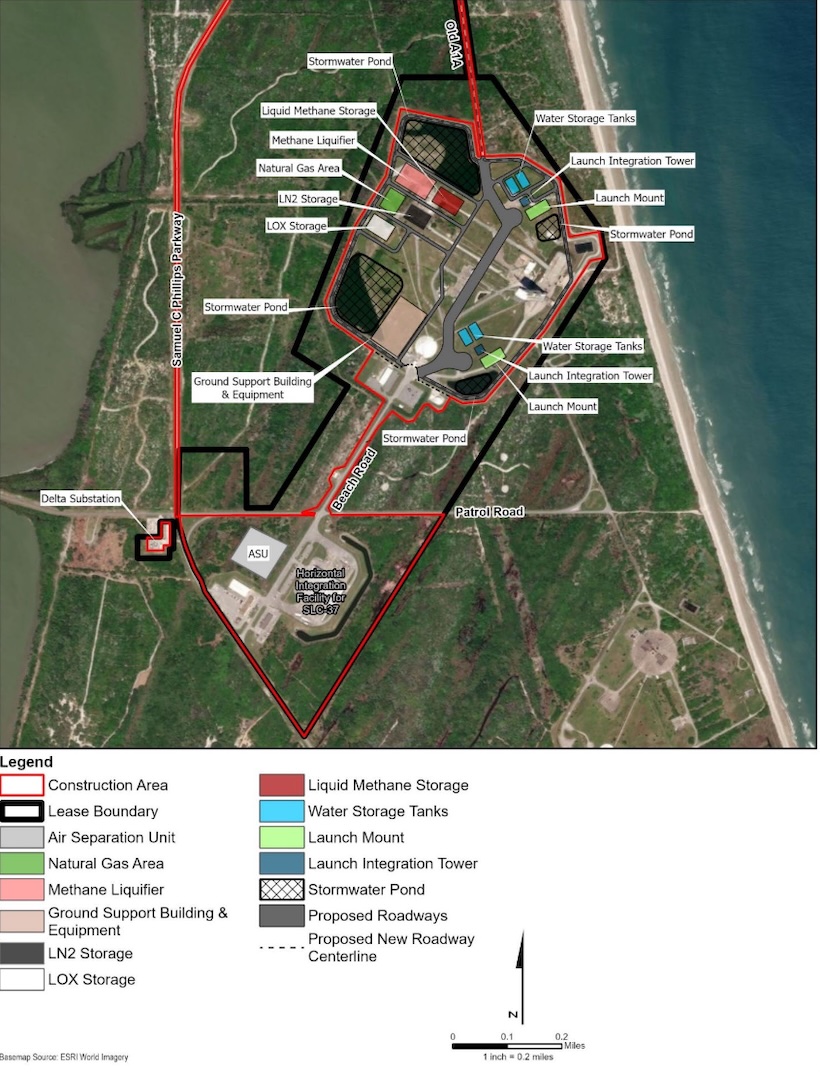

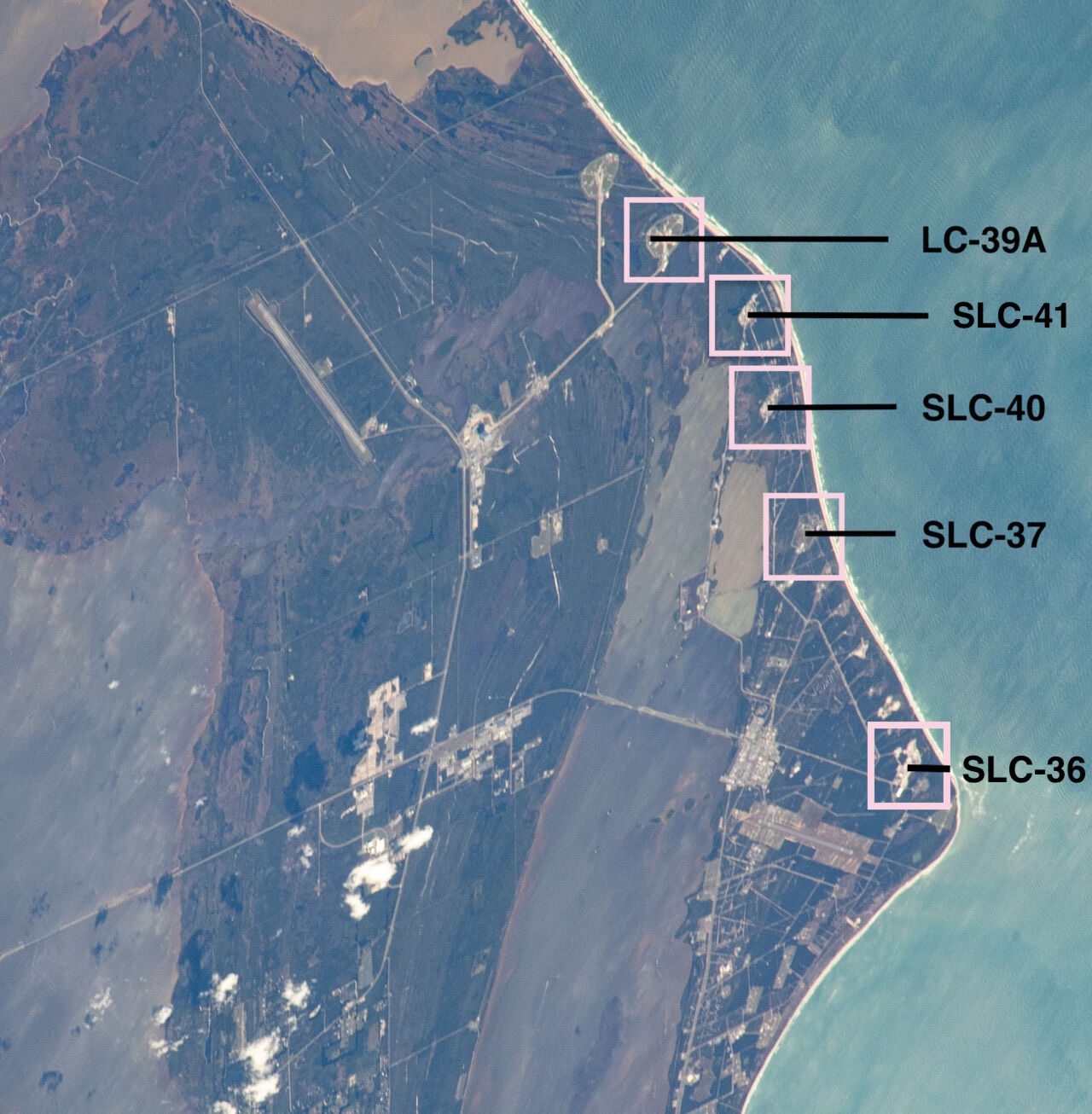

ULA is stacking its third Vulcan rocket. A little more than a week after its most recent Atlas V rocket launch, United Launch Alliance rolled a Vulcan booster to the Vertical Integration Facility at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on July 2 to begin stacking its first post-certification Vulcan rocket, Spaceflight Now reports. The operation, referred to by ULA as Launch Vehicle on Stand (LVOS), is the first major milestone toward the launch of the third Vulcan rocket. The upcoming launch will be the first operational flight of ULA’s new rocket with a pair of US military payloads, following two certification flights in 2024.

For the second time … This is the second time that this particular Vulcan booster was brought to Space Launch Complex 41 in anticipation of a launch campaign. It was previously readied in late October of last year in support of the USSF-106 mission, the Space Force’s designation for the first national security launch to use the Vulcan rocket. However, plans changed as the process of certifying Vulcan to fly government payloads took longer than expected, and ULA pivoted to launch two Atlas V rockets on commercial missions from the same pad before switching back to Vulcan launch preps.

Progress report on China’s Moon rocket. China’s self-imposed deadline of landing astronauts on the Moon by 2030 is now just five years away, and we’re starting to see some tangible progress. Construction of the launch pad for the Long March 10 rocket, the massive vehicle China will use to launch its first crews toward the Moon, is well along at the Wenchang Space Launch Site on Hainan Island. An image shared on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, and then reposted on X, shows the Long March 10’s launch tower near its final height. A mobile launch platform presumably for the Long March 10 is under construction nearby.

Super heavy … The Long March 10 will be China’s most powerful rocket to date, with the ability to dispatch 27 metric tons of payload toward the Moon, a number comparable to NASA’s Space Launch System. Designed for partial reusability, the Long March 10 will use an all-liquid propulsion system and stand more than 92 meters (300 feet) tall. The rocket will launch Chinese astronauts inside the nation’s next-generation Mengzhou crew capsule, along with a lunar lander to transport crew members from lunar orbit to the surface of the Moon using an architecture similar to NASA’s Apollo program.

Next three launches

July 11: Electron | JAKE 4 | Wallops Flight Facility, Virginia | 23: 45 UTC

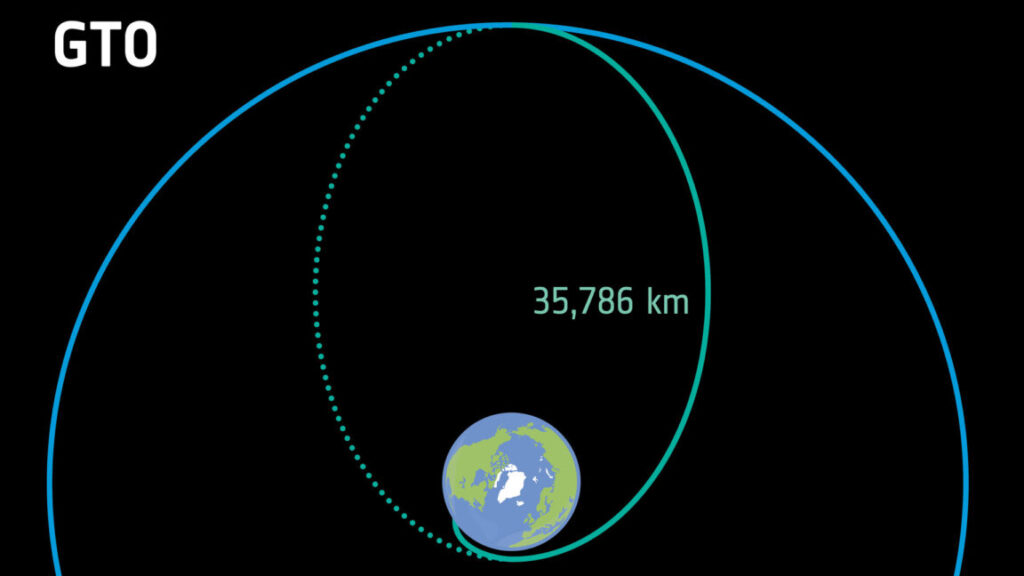

July 13: Falcon 9 | Dror 1 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 04: 31 UTC

July 14: Falcon 9 | Starlink 15-2 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 02: 27 UTC

Rocket Report: SpaceX to make its own propellant; China’s largest launch pad Read More »