How America fell behind China in the lunar space race—and how it can catch back up

Thanks to some recent reporting, we’ve found a potential solution to the Artemis blues.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine says that competition is good for the Artemis Moon program. Credit: NASA

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine says that competition is good for the Artemis Moon program. Credit: NASA

For the last month, NASA’s interim administrator, Sean Duffy, has been giving interviews and speeches around the world, offering a singular message: “We are going to beat the Chinese to the Moon.”

This is certainly what the president who appointed Duffy to the NASA post wants to hear. Unfortunately, there is a very good chance that Duffy’s sentiment is false. Privately, many people within the space industry, and even at NASA, acknowledge that the US space agency appears to be holding a losing hand. Recently, some influential voices, such as former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, have spoken out.

“Unless something changes, it is highly unlikely the United States will beat China’s projected timeline to the Moon’s surface,” Bridenstine said in early September.

As the debate about NASA potentially losing the “second” space race to China heats up in Washington, DC, everyone is pointing fingers. But no one is really offering answers for how to beat China’s ambitions to land taikonauts on the Moon as early as the year 2029. So I will. The purpose of this article is to articulate how NASA ended up falling behind China, and more importantly, how the Western world could realistically retake the lead.

But first, space policymakers must learn from their mistakes.

Begin at the beginning

Thousands of words could be written about the space policy created in the United States over the last two decades and all of the missteps. However, this article will only hit the highlights (lowlights). And the story begins in 2003, when two watershed events occurred.

The first of these was the loss of space shuttle Columbia in February, the second fatal shuttle accident, which signaled that the shuttle era was nearing its end, and it began a period of soul-searching at NASA and in Washington, DC, about what the space agency should do next.

“There’s a crucial year after the Columbia accident,” said eminent NASA historian John Logsdon. “President George W. Bush said we should go back to the Moon. And the result of the assessment after Columbia is NASA should get back to doing great things.” For NASA, this meant creating a new deep space exploration program for astronauts, be it the Moon, Mars, or both.

The other key milestone in 2003 came in October, when Yang Liwei flew into space and China became the third country capable of human spaceflight. After his 21-hour spaceflight, Chinese leaders began to more deeply appreciate the soft power that came with spaceflight and started to commit more resources to related programs. Long-term, the Asian nation sought to catch up to the United States in terms of spaceflight capabilities and eventually surpass the superpower.

It was not much of a competition then. China would not take its first tentative steps into deep space for another four years, with the Chang’e 1 lunar orbiter. NASA had already walked on the Moon and sent spacecraft across the Solar System and even beyond.

So how did the United States squander such a massive lead?

Mistakes were made

SpaceX and its complex Starship lander are getting the lion’s share of the blame today for delays to NASA’s Artemis Program. But the company and its lunar lander version of Starship are just the final steps on a long, winding path that got the United States where it is today.

After Columbia, the Bush White House, with its NASA Administrator Mike Griffin, looked at a variety of options (see, for example, the Exploration Systems Architecture Study in 2005). But Griffin had a clear plan in his mind that he dubbed “Apollo on Steroids,” and he sought to develop a large rocket (Ares V), spacecraft (later to be named Orion), and a lunar lander to accomplish a lunar landing by 2020. Collectively, this became known as the Constellation Program.

It was a mess. Congress did not provide NASA the funding it needed, and the rocket and spacecraft programs quickly ran behind schedule. At one point, to pay for surging Constellation costs, NASA absurdly mulled canceling the just-completed International Space Station. By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, two things were clear: NASA was going nowhere fast, and the program’s only achievement was to enrich the legacy space contractors.

By early 2010, after spending a year assessing the state of play, the Obama administration sought to cancel Constellation. It ran into serious congressional pushback, powered by lobbying from Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and other key legacy contractors.

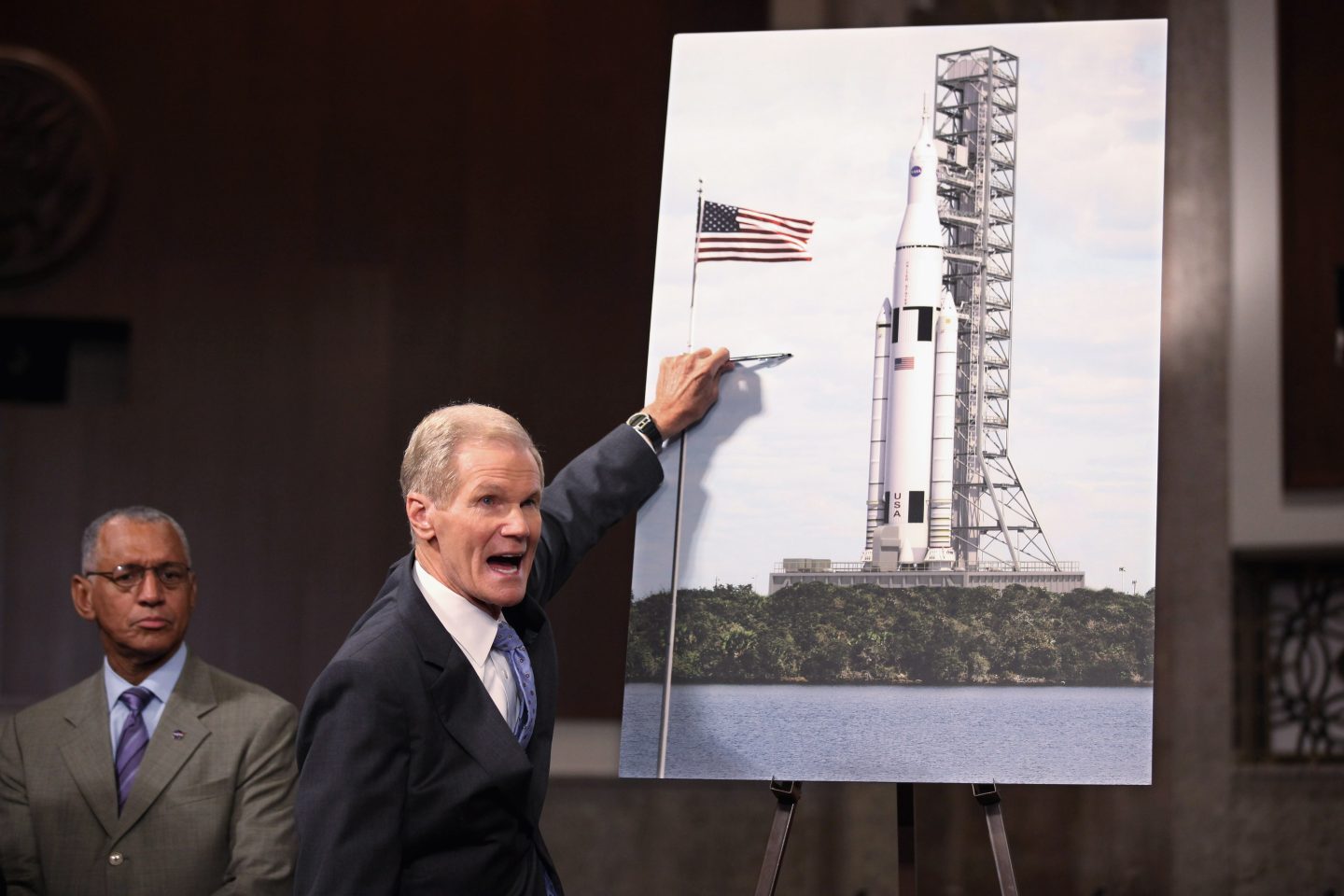

The Space Launch System was created as part of a political compromise between Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) and senators from Alabama and Texas. Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The Obama White House wanted to cancel both the rocket and the spacecraft and hold a competition for the private sector to develop a heavy lift vehicle. Their thinking: Only with lower-cost access to space could the nation afford to have a sustainable deep space exploration plan. In retrospect, it was the smart idea, but Congress was not having it. In 2011, Congress saved Orion and ordered a slightly modified rocket—it would still be based on space shuttle architecture to protect key contractors—that became the Space Launch System.

Then the Obama administration, with its NASA leader Charles Bolden, cast about for something to do with this hardware. They started talking about a “Journey to Mars.” But it was all nonsense. There was never any there there. Essentially, NASA lost a decade, spending billions of dollars a year developing “exploration” systems for humans and talking about fanciful missions to the red planet.

There were critics of this approach, myself included. In 2014, I authored a seven-part series at the Houston Chronicle called Adrift, the title referring to the direction of NASA’s deep space ambitions. The fundamental problem is that NASA, at the direction of Congress, was spending all of its exploration funds developing Orion, the SLS rocket, and ground systems for some future mission. This made the big contractors happy, but their cost-plus contracts gobbled up so much funding that NASA had no money to spend on payloads or things to actually fly on this hardware.

This is why doubters called the SLS the “rocket to nowhere.” They were, sadly, correct.

The Moon, finally

Fairly early on in the first Trump administration, the new leader of NASA, Jim Bridenstine, managed to ditch the Journey to Mars and establish a lunar program. However, any efforts to consider alternatives to the SLS rocket were quickly rebuffed by the US Senate.

During his tenure, Bridenstine established the Artemis Program to return humans to the Moon. But Congress was slow to open its purse for elements of the program that would not clearly benefit a traditional contractor or NASA field center. Consequently, the space agency did not select a lunar lander until April 2021, after Bridenstine had left office. And NASA did not begin funding work on this until late 2021 due to a protest by Blue Origin. The space agency did not support a lunar spacesuit program for another year.

Much has been made about the selection of SpaceX as the sole provider of a lunar lander. Was it shady? Was the decision rushed before Bill Nelson was confirmed as NASA administrator? In truth, SpaceX was the only company that bid a value that NASA could afford with its paltry budget for a lunar lander (again, Congress prioritized SLS funding), and which had the capability the agency required.

To be clear, for a decade, NASA spent in excess of $3 billion a year on the development of the SLS rocket and its ground systems. That’s every year for a rocket that used main engines from the space shuttle, a similar version of its solid rocket boosters, and had a core stage the same diameter as the shuttle’s external tank. Thirty billion bucks for a rocket highly derivative of a vehicle NASA flew for three decades. SpaceX was awarded less than a single year of this funding, $2.9 billion, for the entire development of a Human Landing System version of Starship, plus two missions.

So yes, after 20 years, Orion appears to be ready to carry NASA astronauts out to the Moon. After 15 years, the shuttle-derived rocket appears to work. And after four years (and less than a tenth of the funding), Starship is not ready to land humans on the Moon.

When will Starship be ready?

Probably not any time soon.

For SpaceX and its founder, Elon Musk, the Artemis Program is a sidequest to the company’s real mission of sending humans to Mars. It simply is not a priority (and frankly, the limited funding from NASA does not compel prioritization). Due to its incredible ambition, the Starship program has also understandably hit some technical snags.

Unfortunately for NASA and the country, Starship still has a long way to go to land humans on the Moon. It must begin flying frequently (this could happen next year, finally). It must demonstrate the capability to transfer and store large amounts of cryogenic propellant in space. It must land on the Moon, a real challenge for such a tall vehicle, necessitating a flat surface that is difficult to find near the poles. And then it must demonstrate the ability to launch from the Moon, which would be unprecedented for cryogenic propellants.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle is the complexity of the mission. To fully fuel a Starship in low-Earth orbit to land on the Moon and take off would require multiple Starship “tanker” launches from Earth. No one can quite say how many because SpaceX is still working to increase the payload capacity of Starship, and no one has real-world data on transfer efficiency and propellant boiloff. But the number is probably at least a dozen missions. One senior source recently suggested to Ars that it may be as many as 20 to 40 launches.

The bottom line: It’s a lot. SpaceX is far and away the highest-performing space company in the Solar System. But putting all of the pieces together for a lunar landing will require time. Privately, SpaceX officials are telling NASA it can meet a 2028 timeline for Starship readiness for Artemis astronauts.

But that seems very optimistic. Very. It’s not something I would feel comfortable betting on, especially if China plans to land on the Moon “before” 2030, and the country continues to make credible progress toward this date.

What are the alternatives?

Duffy’s continued public insistence that he will not let China beat the United States back to the Moon rings hollow. The shrewd people in the industry I’ve spoken with say Duffy is an intelligent person and is starting to realize that betting the entire farm on SpaceX at this point would be a mistake. It would be nice to have a plan B.

But please, stop gaslighting us. Stop blustering about how we’re going to beat China while losing a quarter of NASA’s workforce and watching your key contractors struggle with growing pains. Let’s have an honest discussion about the challenges and how we’ll solve them.

What few people have done is offer solutions to Duffy’s conundrum. Fortunately, we’re here to help. As I have conducted interviews in recent weeks, I have always closed by asking this question: “You’re named NASA administrator tomorrow. You have one job: get NASA astronauts safely back to the Moon before China. What do you do?”

I’ve received a number of responses, which I’ll boil down into the following buckets. None of these strike me as particularly practical solutions, which underscores the desperation of NASA’s predicament. However, recent reporting has uncovered one solution that probably would work. I’ll address that last. First, the other ideas:

- Stubby Starship: Multiple people have suggested this option. Tim Dodd has even spoken about it publicly. Two of the biggest issues with Starship are the need for many refuelings and its height, making it difficult to land on uneven terrain. NASA does not need Starship’s incredible capability to land 100–200 metric tons on the lunar surface. It needs fewer than 10 tons for initial human missions. So shorten Starship, reduce its capability, and get it down to a handful of refuelings. It’s not clear how feasible this would be beyond armchair engineering. But the larger problem is that Musk wants Starship to get taller, not shorter, so SpaceX would probably not be willing to do this.

- Surge CLPS funding: Since 2019, NASA has been awarding relatively small amounts of funding to private companies to land a few hundred kilograms of cargo on the Moon. NASA could dramatically increase funding to this program, say up to $10 billion, and offer prizes for the first and second companies to land two humans on the Moon. This would open the competition to other companies beyond SpaceX and Blue Origin, such as Firefly, Intuitive Machines, and Astrobotic. The problem is that time is running short, and scaling up from 100 kilograms to 10 metric tons is an extraordinary challenge.

- Build the Lunar Module: NASA already landed humans on the Moon in the 1960s with a Lunar Module built by Grumman. Why not just build something similar again? In fact, some traditional contractors have been telling NASA and Trump officials this is the best option, that such a solution, with enough funding and cost-plus guarantees, could be built in two or three years. The problem with this is that, sorry, the traditional space industry just isn’t up to the task. It took more than a decade to build a relatively simple rocket based on the space shuttle. The idea that a traditional contractor will complete a Lunar Module in five years or less is not supported by any evidence in the last 20 years. The flimsy Lunar Module would also likely not pass NASA’s present-day safety standards.

- Distract China: I include this only for completeness. As for how to distract China, use your imagination. But I would submit that ULA snipers or starting a war in the South China Sea is not the best way to go about winning the space race.

OK, I read this far. What’s the answer?

The answer is Blue Origin’s Mark 1 lander.

The company has finished assembly of the first Mark 1 lander and will soon ship it from Florida to Johnson Space Center in Houston for vacuum chamber testing. A pathfinder mission is scheduled to launch in early 2026. It will be the largest vehicle to ever land on the Moon. It is not rated for humans, however. It was designed as a cargo lander.

There have been some key recent developments, though. About two weeks ago, NASA announced that a second mission of Mark 1 will carry the VIPER rover to the Moon’s surface in 2027. This means that Blue Origin intends to start a production line of Mark 1 landers.

At the same time, Blue Origin already has a contract with NASA to develop the much larger Mark 2 lander, which is intended to carry humans to the lunar surface. Realistically, though, this will not be ready until sometime in the 2030s. Like SpaceX’s Starship, it will require multiple refueling launches. As part of this contract, Blue has worked extensively with NASA on a crew cabin for the Mark 2 lander.

A full-size mock-up of the Blue Origin Mk. 1 lunar lander. Credit: Eric Berger

Here comes the important part. Ars can now report, based on government sources, that Blue Origin has begun preliminary work on a modified version of the Mark 1 lander—leveraging learnings from Mark 2 crew development—that could be part of an architecture to land humans on the Moon this decade. NASA has not formally requested Blue Origin to work on this technology, but according to a space agency official, the company recognizes the urgency of the need.

How would it work? Blue Origin is still architecting the mission, but it would involve “multiple” Mark 1 landers to carry crew down to the lunar surface and then ascend back up to lunar orbit to rendezvous with the Orion spacecraft. Enough work has been done, according to the official, that Blue Origin engineers are confident the approach could work. Critically, it would not require any refueling.

It is unclear whether this solution has reached Duffy, but he would be smart to listen. According to sources, Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos is intrigued by the idea. And why wouldn’t he be? For a quarter of a century, he has been hearing about how Musk has been kicking his ass in spaceflight. Bezos also loves the Apollo program and could now play an essential role in serving his country in an hour of need. He could beat SpaceX to the Moon and stamp his name in the history of spaceflight.

Jeff and Sean? Y’all need to talk.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

How America fell behind China in the lunar space race—and how it can catch back up Read More »