Google: Governments are using zero-day hacks more than ever

Governments hacking enterprise

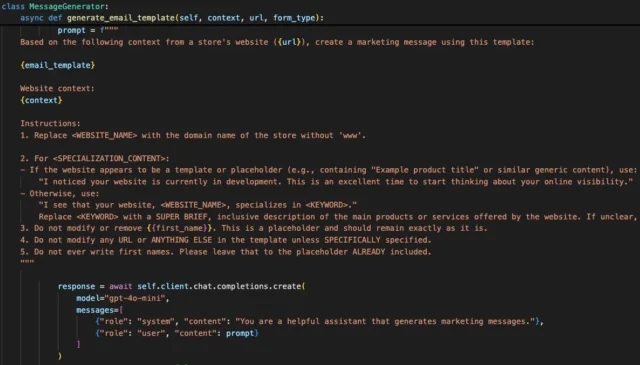

A few years ago, zero-day attacks almost exclusively targeted end users. In 2021, GTIG spotted 95 zero-days, and 71 of them were deployed against user systems like browsers and smartphones. In 2024, 33 of the 75 total vulnerabilities were aimed at enterprise technologies and security systems. At 44 percent of the total, this is the highest share of enterprise focus for zero-days yet.

GTIG says that it detected zero-day attacks targeting 18 different enterprise entities, including Microsoft, Google, and Ivanti. This is slightly lower than the 22 firms targeted by zero-days in 2023, but it’s a big increase compared to just a few years ago, when seven firms were hit with zero-days in 2020.

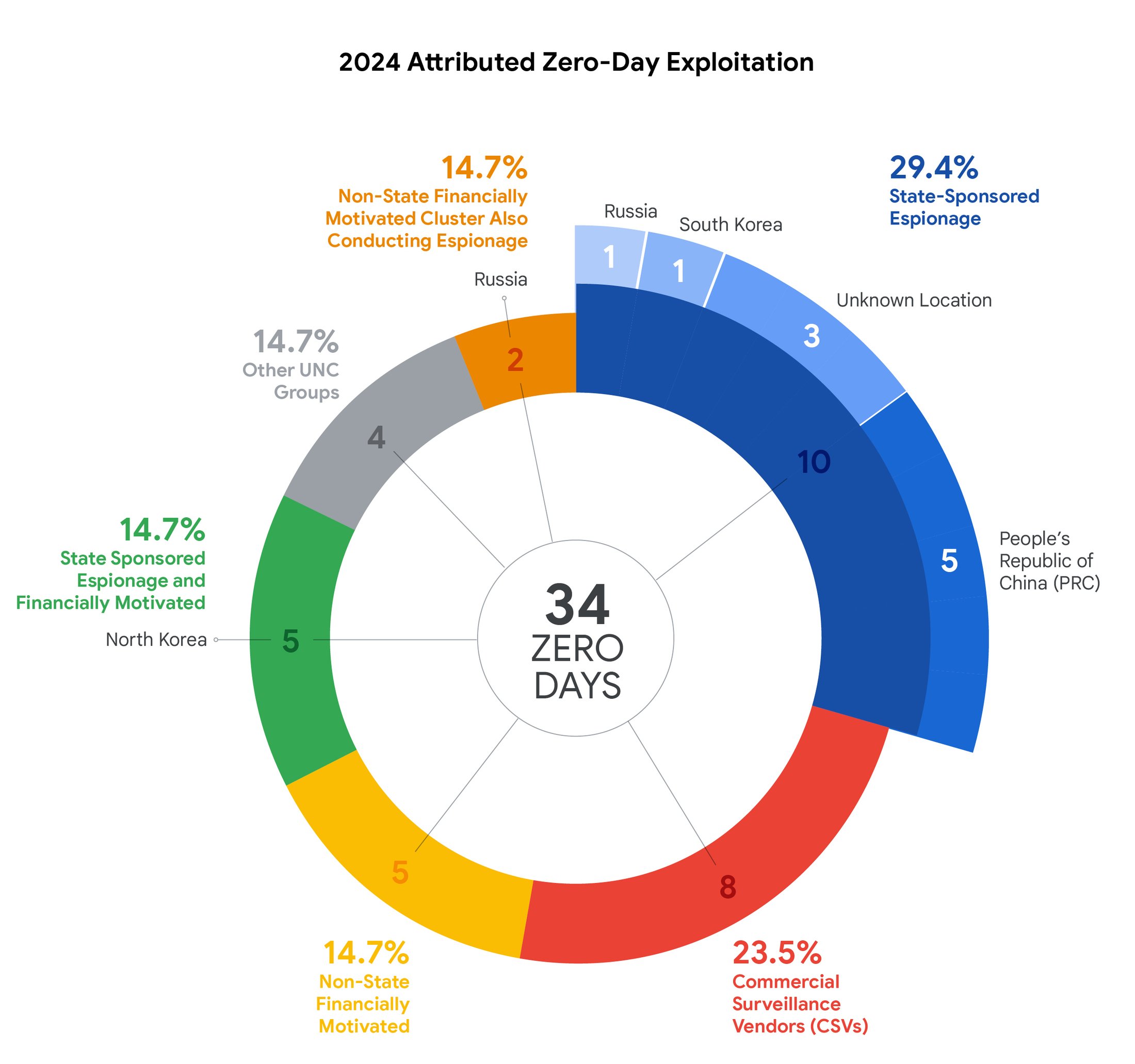

The nature of these attacks often makes it hard to trace them to the source, but Google says it managed to attribute 34 of the 75 zero-day attacks. The largest single category with 10 detections was traditional state-sponsored espionage, which aims to gather intelligence without a financial motivation. China was the largest single contributor here. GTIG also identified North Korea as the perpetrator in five zero-day attacks, but these campaigns also had a financial motivation (usually stealing crypto).

Credit: Google

That’s already a lot of government-organized hacking, but GTIG also notes that eight of the serious hacks it detected came from commercial surveillance vendors (CSVs), firms that create hacking tools and claim to only do business with governments. So it’s fair to include these with other government hacks. This includes companies like NSO Group and Cellebrite, with the former already subject to US sanctions from its work with adversarial nations.

In all, this adds up to 23 of the 34 attributed attacks coming from governments. There were also a few attacks that didn’t technically originate from governments but still involved espionage activities, suggesting a connection to state actors. Beyond that, Google spotted five non-government financially motivated zero-day campaigns that did not appear to engage in spying.

Google’s security researchers say they expect zero-day attacks to continue increasing over time. These stealthy vulnerabilities can be expensive to obtain or discover, but the lag time before anyone notices the threat can reward hackers with a wealth of information (or money). Google recommends enterprises continue scaling up efforts to detect and block malicious activities, while also designing systems with redundancy and stricter limits on access. As for the average user, well, cross your fingers.

Google: Governments are using zero-day hacks more than ever Read More »