Rocket Report: China tests Falcon 9 lookalike; NASA’s Moon rocket fully stacked

A South Korean rocket startup will soon make its first attempt to reach low-Earth orbit.

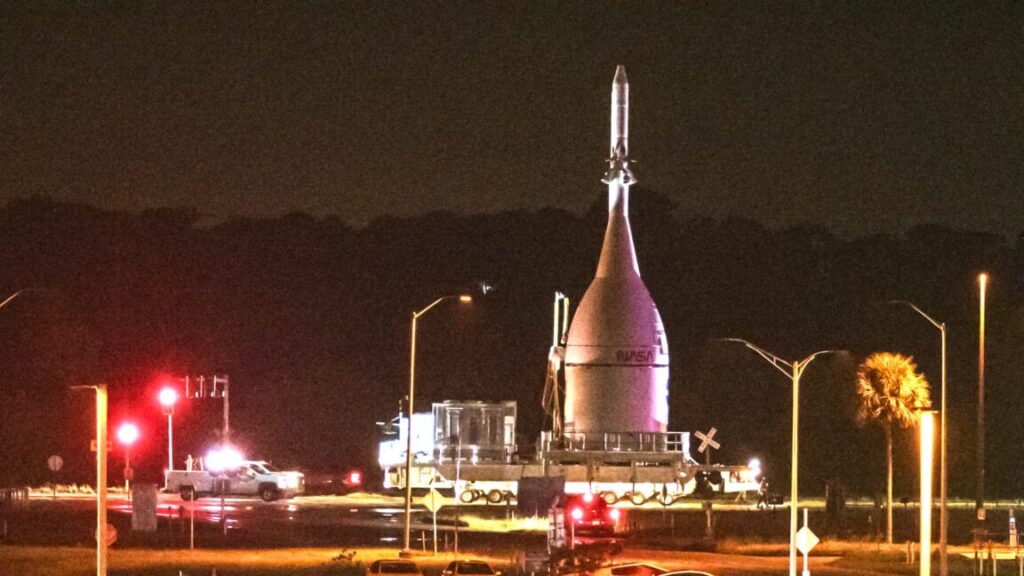

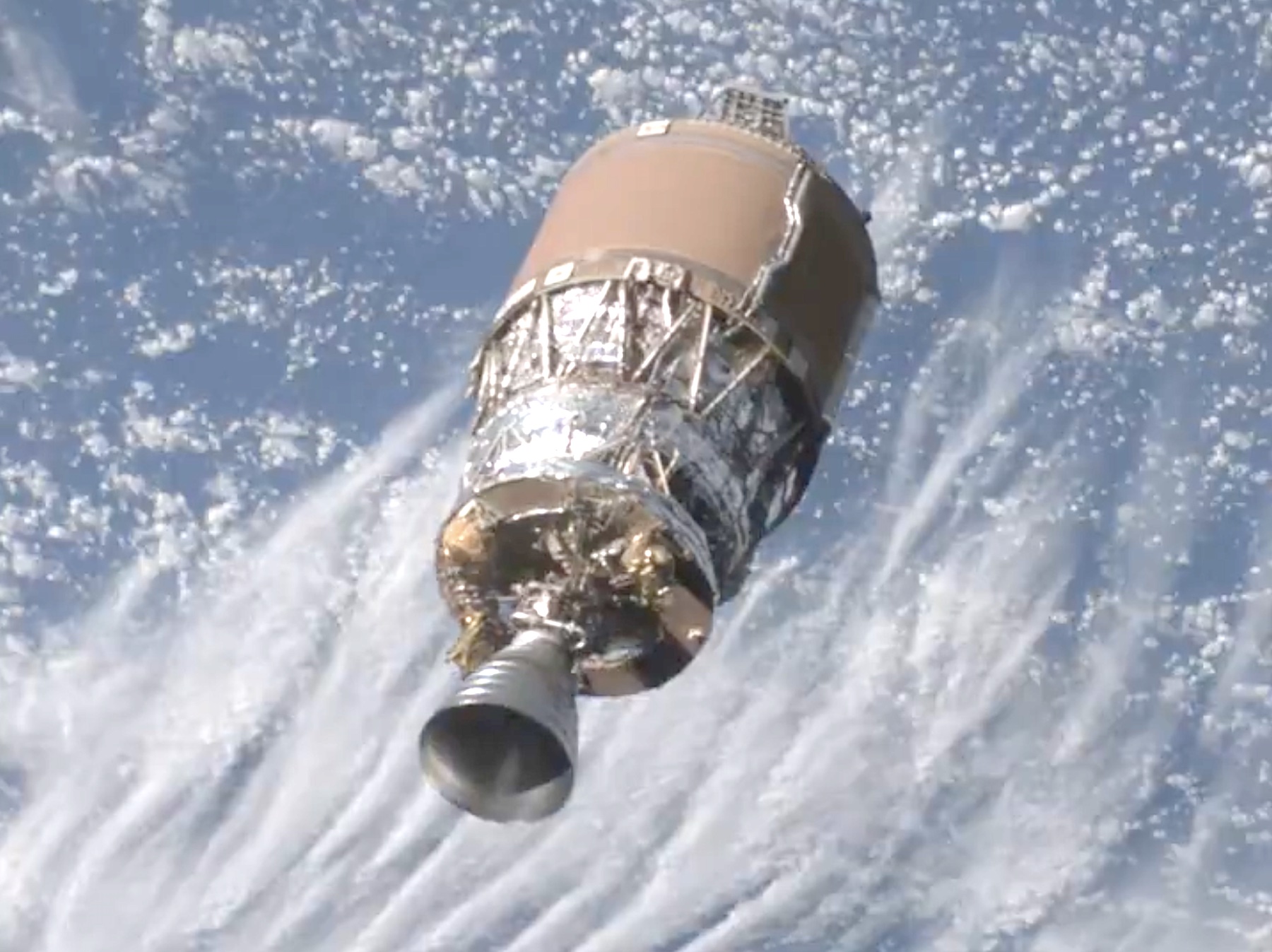

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis II mission is lowered on top of the Space Launch System rocket at Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

Welcome to Edition 8.16 of the Rocket Report! The 10th anniversary of SpaceX’s first Falcon 9 rocket landing is coming up at the end of this year. We’re still waiting for a second company to bring back an orbital-class booster from space for a propulsive landing. Two companies, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin and China’s LandSpace, could join SpaceX’s exclusive club as soon as next month. (Bezos might claim he’s already part of the club, but there’s a distinction to be made.) Each company is in the final stages of launch preparations—Blue Origin for its second New Glenn rocket, and LandSpace for the debut flight of its Zhuque-3 rocket. Blue Origin and LandSpace will both attempt to land their first stage boosters downrange from their launch sites. They’re not exactly in a race with one another, but it will be fascinating to see how New Glenn and Zhuque-3 perform during the uphill and downhill phases of flight, and whether one or both of the new rockets stick the landing.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

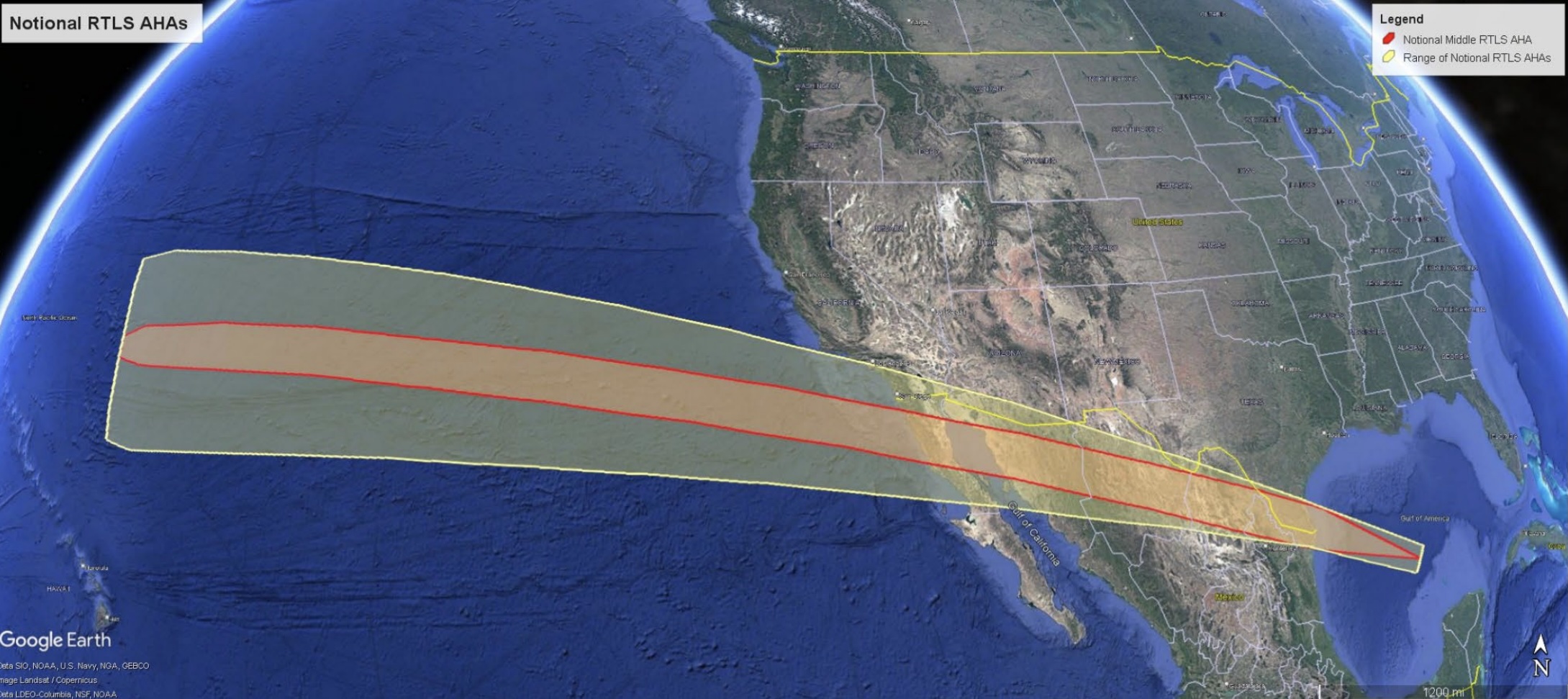

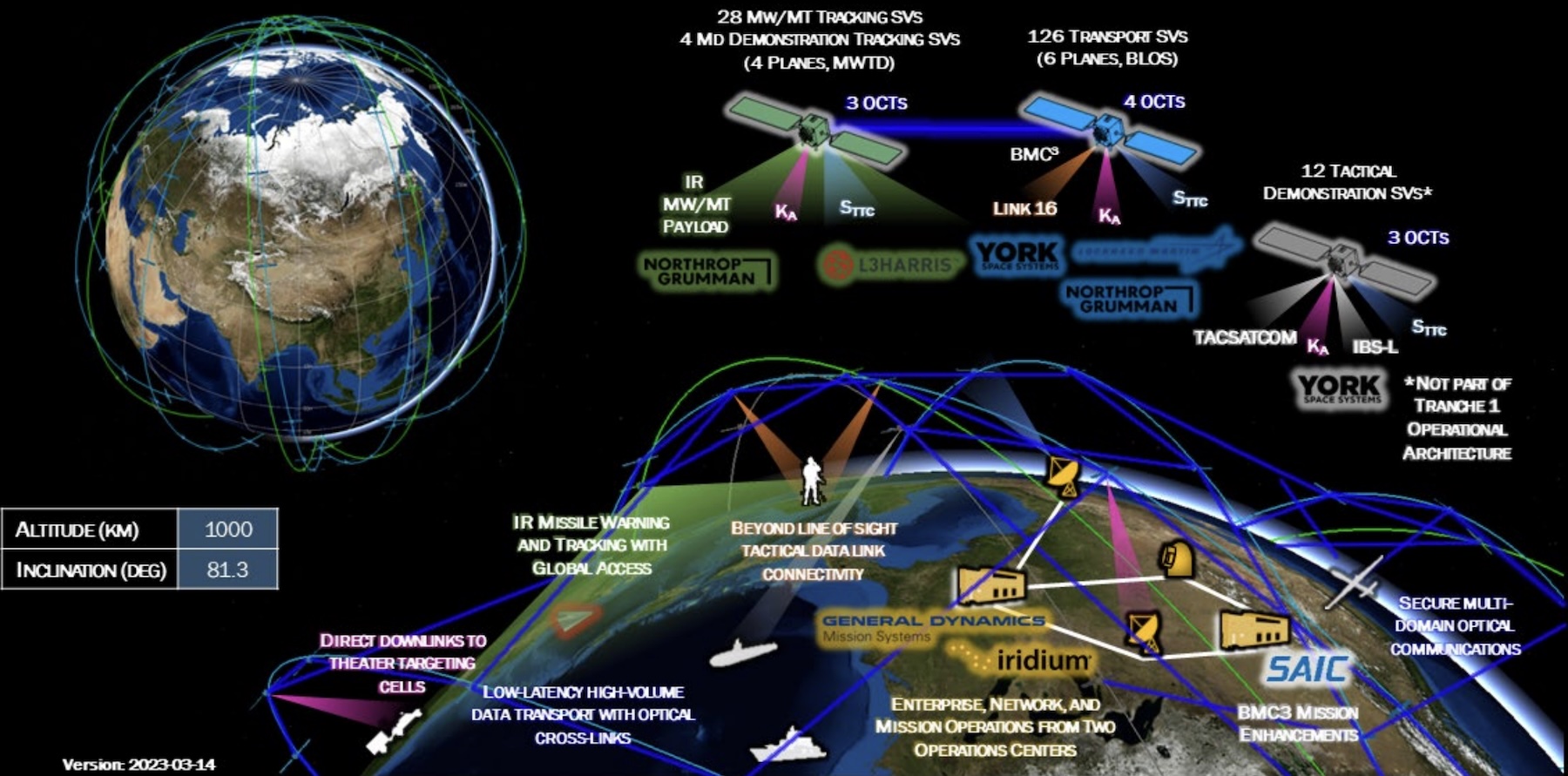

The race for space-based interceptors. The Trump administration’s announcement of the Golden Dome missile defense shield has set off a race among US companies to develop and test space weapons, some of them on their own dime, Ars reports. One of these companies is a 3-year-old startup named Apex, which announced plans to test a space-based interceptor as soon as next year. Apex’s concept will utilize one of the company’s low-cost satellite platforms outfitted with an “Orbital Magazine” containing multiple interceptors, which will be supplied by an undisclosed third-party partner. The demonstration in low-Earth orbit could launch as soon as June 2026 and will test-fire two interceptors from Apex’s Project Shadow spacecraft. The prototype interceptors could pave the way for operational space-based interceptors to shoot down ballistic missiles. (submitted by biokleen)

Usual suspects … Traditional defense contractors are also getting in the game. Northrop Grumman’s CEO, Kathy Warden, said earlier this year that her company is already testing space-based interceptor components on the ground. This week, Lockheed Martin announced it is on a path to test a space-based interceptor in orbit by 2028. Neither company has discussed as much detail of their plans as Apex revealed this week.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Lockheed Martin’s latest “New Space” investment. As interest grows in rotating detonation engines for hypersonic flight, a startup specialist in the technology says it will receive backing from Lockheed Martin’s corporate venture capital arm, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. The strategic investment by Lockheed Martin Ventures “reflects the potential of Venus’s dual-use technology” in an era of growing defense and space spending, Venus Aerospace said in a statement. Venus said its partnership with Lockheed Martin combines the former’s startup mindset with the latter’s resources and industry expertise. The companies did not announce the value of Lockheed’s investment, but Venus said it has raised $106 million since its founding in 2020. Lockheed Martin Ventures has made similar investments in other rocket startups, including Rocket Lab in 2015.

What’s this actually for? … Houston-based Venus Aerospace completed a high-thrust test flight of its Rotating Detonation Rocket Engine (RDRE) in May from Spaceport America, New Mexico. Rotating detonation engine technology is interesting because it has the potential to significantly increase fuel efficiency in various applications, from Navy carriers to rocket engines, Ars reported earlier this year. The engine works by producing a shockwave with a flow of detonation traveling through a circular channel. The engine harnesses these supersonic detonation waves to generate thrust. “Venus has proven in flight the most efficient rocket engine technology in history,” said Sassie Duggleby, co-founder and CEO of Venus Aerospace. “With support from Lockheed Martin Ventures, we will advance our capabilities to deliver at scale and deploy the engine that will power the next 50 years of defense, space, and commercial high-speed aviation.”

South Korean startup receives permission to fly. Innospace announced on October 20 that it has received South Korea’s first private commercial launch permit from the Korea AeroSpace Administration,” the Chosun Daily reports. Accordingly, Innospace will launch its independently developed “HANBIT-Nano” launch vehicle from a Brazilian launch site as early as late this month. Innospace stated that the launch window for this mission has been set for October 28 through November 28. The launch site is the Alcântara Space Center, operated by the Brazilian Air Force.

Aiming for LEO … This will be the first flight of Innospace’s HANBIT-Nano launch vehicle, standing roughly 72 feet (22 meters) tall with a diameter of 4.6 feet (1.4 meters). The two-stage rocket is powered by hybrid propulsion, consuming a mixture of paraffin and liquid oxygen. For its debut flight, the rocket will target an orbit about 300 kilometers (186 miles) high with a batch of small satellites from customers in South Korea, Brazil, and India. According to Innospace, HANBIT-Nano can lift about 200 pounds (90 kilograms) of payload into orbit.

A new record for rocket reuse. SpaceX’s launch of a Falcon 9 rocket from Florida on October 19 set a new record for reusable rockets, Ars reports. It marked the 31st launch of the company’s most-flown Falcon 9 booster. The rocket landed on SpaceX’s recovery ship in the Atlantic Ocean to be returned to Florida for a 32nd flight. Several more rockets in SpaceX’s inventory are nearing their 30th launch. In all, SpaceX has more than 20 Falcon 9 boosters in its fleet on both the East and West Coasts. SpaceX engineers are now certifying the Falcon 9 boosters for up to 40 flights apiece.

10,000 and counting … SpaceX’s two launches last weekend weren’t just noteworthy for Falcon 9 lore. Hours after setting the new booster reuse record, SpaceX deployed a batch of 28 Starlink satellites from a different rocket after lifting off from California. This mission propelled SpaceX’s Starlink program past a notable milestone. With the satellites added to the constellation on Sunday, the company has delivered more than 10,000 mass-produced Starlink spacecraft to low-Earth orbit. The exact figure stands at 10,006 satellites, according to a tabulation by Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist who expertly tracks comings and goings between Earth and space. About 8,700 of these Starlink satellites are still in orbit, with SpaceX adding more every week.

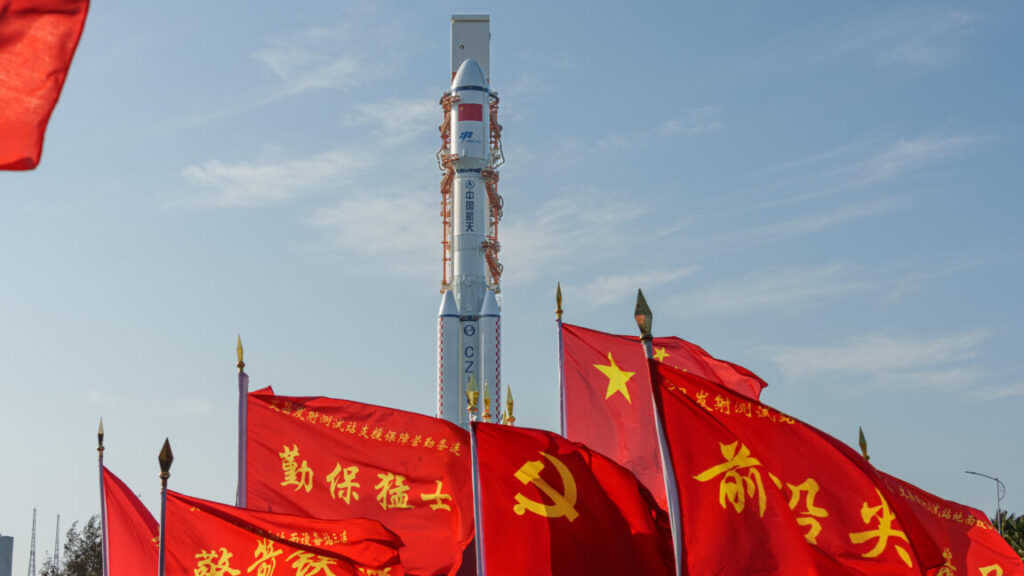

China is on the cusp of something big. Launch startup LandSpace is in the final stages of preparations for the first flight of its Zhuque-3 rocket and a potentially landmark mission for China, Space News reports. LandSpace said it completed the first phase of the Zhuque-3 rocket’s inaugural launch campaign this week. The Zhuque-3 is the largest commercial rocket developed to date in China, nearly matching the size and performance of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, with nine first stage engines and a single upper stage engine. One key difference is that the Zhuque-3 burns methane fuel, while Falcon 9’s engines consume kerosene. Most notably, LandSpace will attempt to land the rocket’s first stage booster at a location downrange from the launch site, similar to the way SpaceX lands Falcon 9 boosters on drone ships at sea. Zhuque-3’s first stage will aim for a land-based site in an experiment that could pave the way for LandSpace to reuse rockets in the future.

Testing status … The recent testing at Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern China included a propellant loading demonstration and a static fire test of the rocket’s first stage engines. Earlier this week, LandSpace integrated the payload fairing on the rocket. The company said it will return the rocket to a nearby facility “for inspection and maintenance in preparation for its upcoming orbital launch and first stage recovery.” The launch is expected to happen as soon as next month.

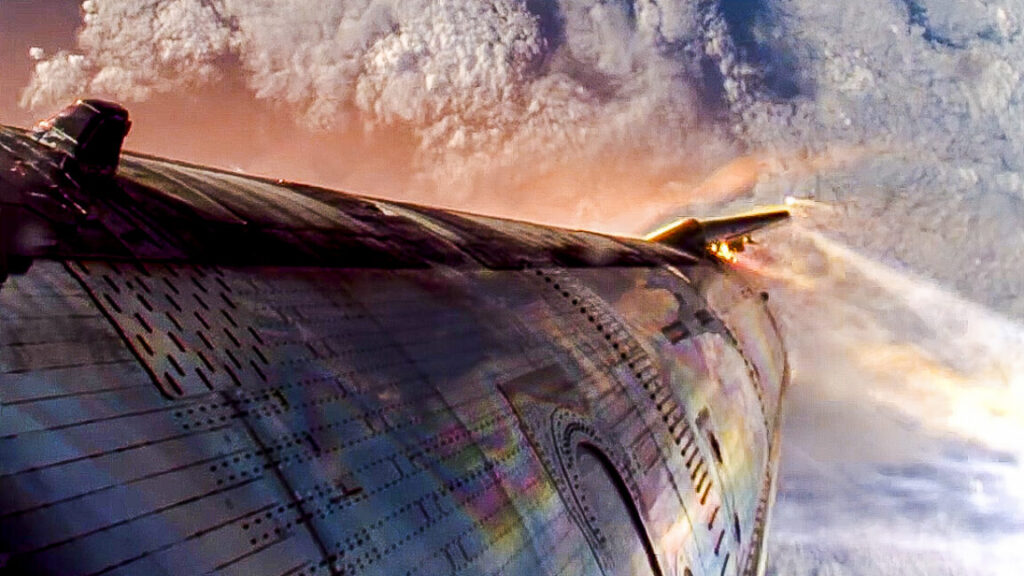

Uprated Ariane 6 won’t launch until next year. Arianespace has confirmed that the first flight of the more powerful, four-booster variant of the Ariane 6 rocket will not be launched until 2026, European Spaceflight reports. The first Ariane 64 rocket had been expected to launch in late 2025, carrying the first batch of Amazon’s Project Kuiper satellites. On October 16, Arianespace announced the fourth and final Ariane 6 flight of the year would carry a pair of Galileo satellites for Europe’s global satellite navigation system in December. This will follow an already-scheduled Ariane 6 launch scheduled for November 4. Both of the upcoming flights will employ the same Ariane 6 configuration used on all of the rocket’s flights to date. This version, known as Ariane 62, has two strap-on solid rocket boosters.

Kuiper soon … The Ariane 64 variant will expose the rocket to stronger forces coming from four solid rocket boosters, each producing about a million pounds (4,500 kilonewtons) of thrust. ArianeGroup, the rocket’s manufacturer, said a year ago that it completed qualification of the Ariane 6 upper stage to withstand the stronger launch loads. Arianespace didn’t offer any explanation of the Ariane 64’s delay from this year to next, but it did confirm the uprated rocket will be the company’s first flight of 2026. The mission will be the first of 18 Arianespace flights dedicated to launching Amazon’s Project Kuiper broadband satellites, adding Ariane 6 to the mix of rockets deploying the Internet network in low-Earth orbit.

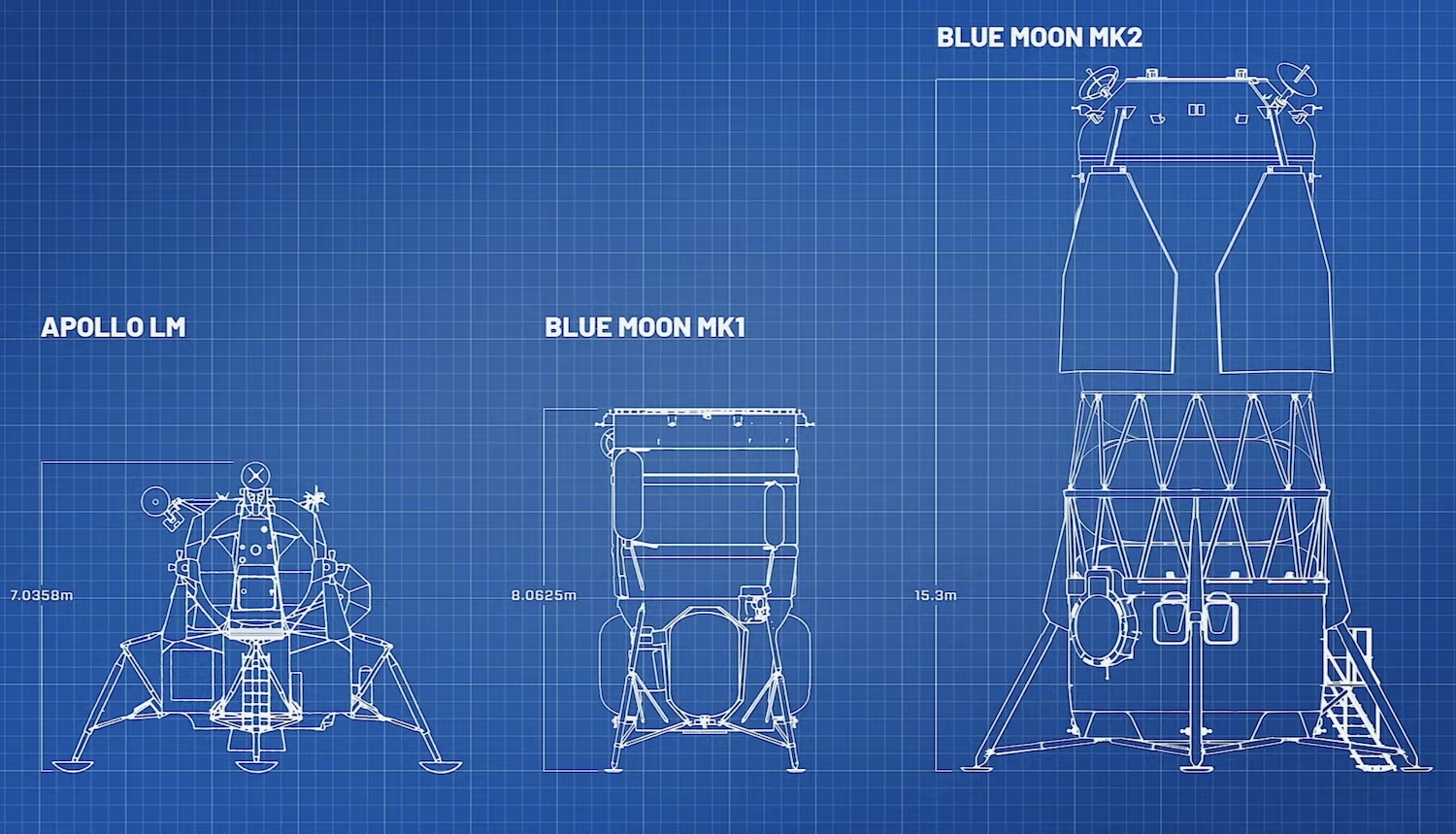

Duffy losing confidence in Starship. NASA acting Administrator Sean Duffy made two television appearances on Monday morning in which he shook up the space agency’s plans to return humans to the Moon, Ars reports. Speaking on Fox News, where the secretary of transportation frequently appears in his acting role as NASA chief, Duffy said SpaceX has fallen behind in developing the Starship vehicle as a lunar lander. Duffy also indirectly acknowledged that NASA’s projected target of a 2027 crewed lunar landing is no longer achievable. Accordingly, he said he intended to expand the competition to develop a lander capable of carrying humans down to the Moon from lunar orbit and back.

The rest of the story … “They’re behind schedule, and so the President wants to make sure we beat the Chinese,” Duffy said of SpaceX. “He wants to get there in his term. So I’m in the process of opening that contract up. I think we’ll see companies like Blue [Origin] get involved, and maybe others. We’re going to have a space race in regard to American companies competing to see who can actually lead us back to the Moon first.” The timing of Duffy’s public appearances on Monday seems tailored to influence a fierce, behind-the-scenes battle to hold onto the NASA leadership position. Jared Isaacman, who Trump nominated and then withdrew for the NASA posting, is again under consideration at the White House to become the agency’s next full-time administrator. (submitted by zapman987)

Rocket fully stacked for Artemis II. “The last major hardware component before Artemis II launches early next year has been installed,” NASA’s acting Administrator Sean Duffy posted on X Monday. Over the weekend, ground teams at Kennedy Space Center in Florida hoisted the Orion spacecraft for the Artemis II mission atop its Space Launch System rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building. This followed the transfer of the Orion spacecraft to the VAB from a nearby processing facility last week. With Orion installed, the rocket is fully assembled to its complete height of 322 feet (98 meters) tall.

Four months away? … NASA is still officially targeting no earlier than February 5, 2026, for the launch of the Artemis II mission. This will be the first flight of astronauts to the vicinity of the Moon since 1972, and the first glimpse of human spaceflight beyond low-Earth orbit for several generations. Upcoming milestones in the Artemis II launch campaign include a countdown demonstration inside the VAB, where the mission’s four-person crew will take their seats in the Orion spacecraft to simulate what they’ll go through on launch day.

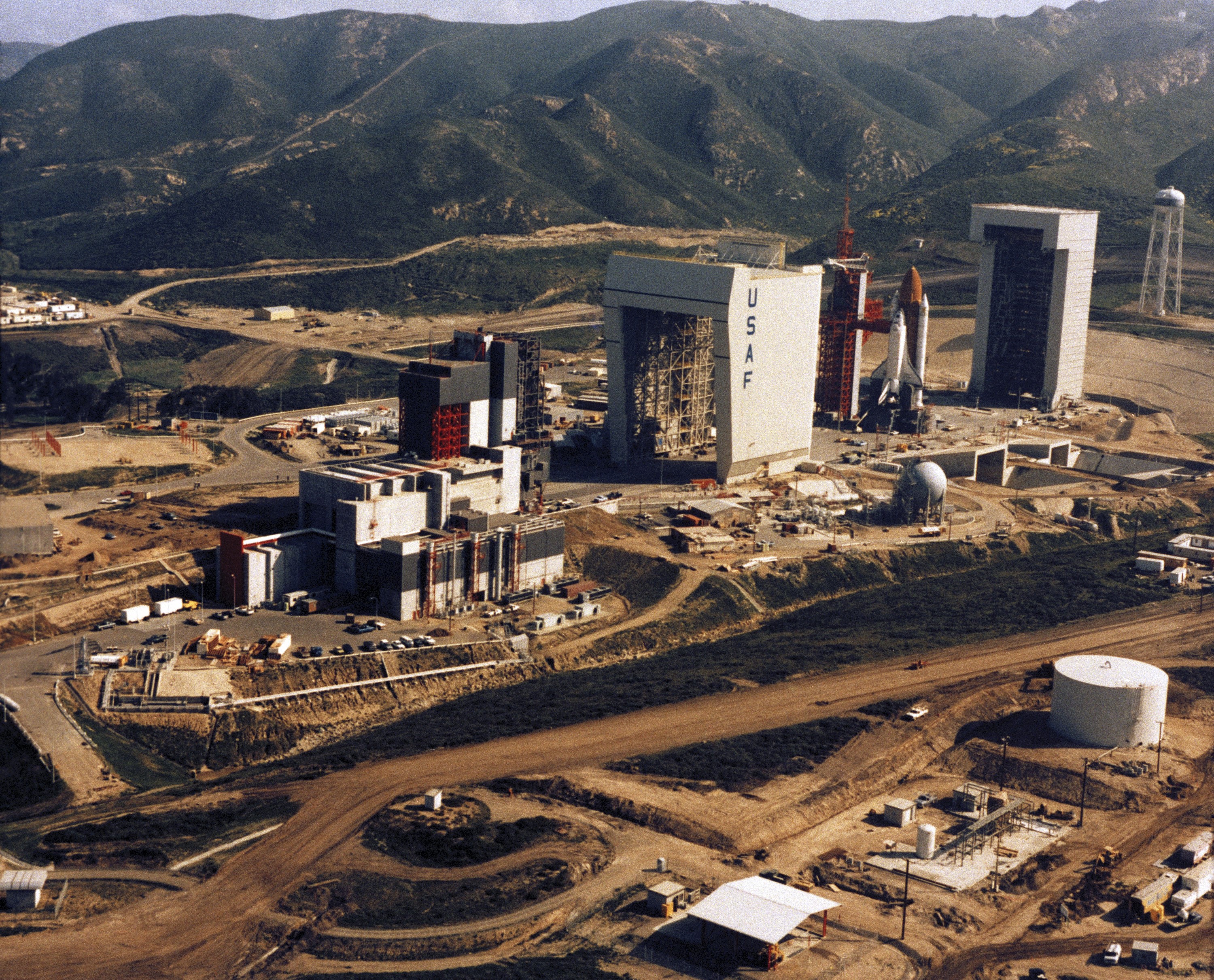

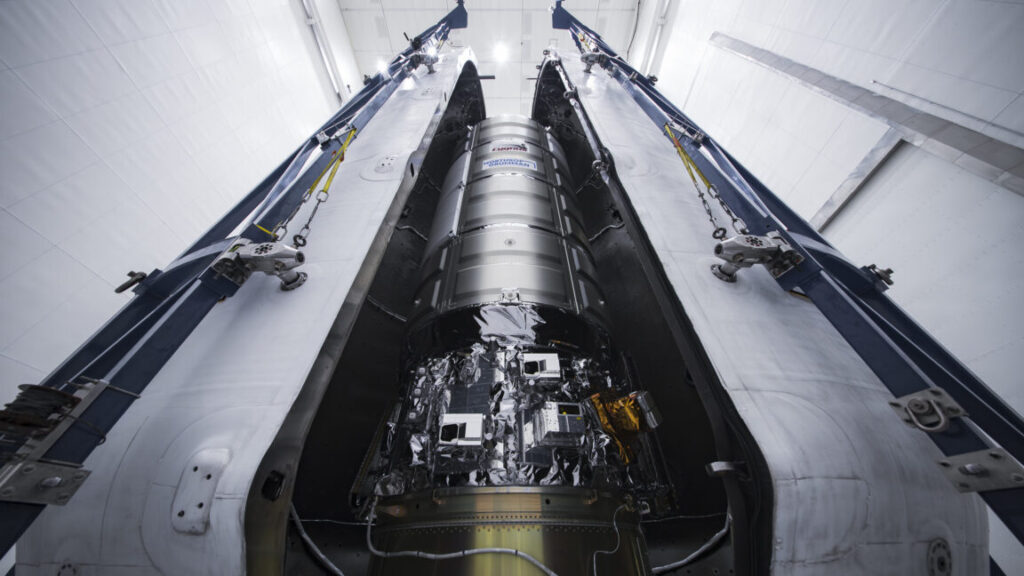

New Glenn staged for rollout. Dave Limp, Blue Origin’s CEO, posted a video this week of the company’s second New Glenn rocket undergoing launch preparations inside a hangar at Launch Complex 36 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The rocket’s first and second stages are now mated together and installed on the transporter erector that will carry them from the hangar to the launch pad. “We will spend the next days on final checkouts and connecting the umbilicals. Stay tuned for rollout and hotfire!” Limp wrote.

“Big step toward launch” … The connection of New Glenn’s stages and integration on the transporter erector marks a “big step toward launch,” Limp wrote. A launch sometime in November is still possible if engineers can get through a smooth test-firing of the rocket’s seven main engines on the launch pad. The rocket will send two NASA spacecraft on a journey to Mars.

China launches clandestine satellite. China launched a Long March 5 rocket Thursday with a classified military satellite heading toward geosynchronous orbit, Space News reports. The satellite is named TJS-20, and the circumstances of the launch—using China’s most powerful operational rocket—suggest TJS-20 could be the next in a line of signals intelligence-gathering missions. The previous satellite of this line, TJS-11, launched in February 2024, also on a Long March 5.

Doing a lot … This launch continued China’s increasing use of the Long March 5 and its sister variant, the Long March 5B. The Long March 5 is expendable, and although we don’t know how much it costs, it can’t be cheap. It is a complex rocket powered by 10 engines on its core stage and four boosters, some burning liquid hydrogen fuel and others burning kerosene. The second stage also has two cryogenically fueled engines. The Long March 5 has now flown 16 times in nine years and seven times within the last two years. The uptick in launches is largely due to China’s use of the Long March 5 to launch satellites for the Guowang megaconstellation.

Next three launches

Oct. 25: Falcon 9 | Starlink 11-12 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 14: 00 UTC

Oct. 26: H3 | HTV-X 1 | Tanegashima Space Center, Japan | 00: 00 UTC

Oct. 26: Long March 3B/E | Unknown Payload | Xichang Satellite Launch Center | 03: 50 UTC

Rocket Report: China tests Falcon 9 lookalike; NASA’s Moon rocket fully stacked Read More »