Rocket Report: SpaceX launch prices are going up; Russia fixes broken launch pad

It looks like United Launch Alliance will build more upper stages for NASA’s SLS rocket.

A welder works on repairs to the Soyuz launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Credit: Roscosmos

Welcome to Edition 8.32 of the Rocket Report! The big news this week is NASA’s shake-up of the Artemis program. On paper, at least, the changes appear to be quite sensible. Canceling the big, new upper stage for the Space Launch System rocket and replacing it with a commercial upper stage, almost certainly United Launch Alliance’s Centaur stage, should result in cost savings. The changes also relieve some of the pressure for SpaceX and Blue Origin to rapidly demonstrate cryogenic refueling in low-Earth orbit. The Artemis III mission is now a low-Earth orbit mission, using SLS and the Orion spacecraft to dock with one or both of the Artemis program’s human-rated lunar landers just a few hundred miles above the Earth—no refueling required. Artemis IV will now be the first lunar landing attempt.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Sentinel missile nears first flight. The US Air Force’s new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile is on track for its first test flight next year, military officials reaffirmed last week. The LGM-35A Sentinel will replace the Air Force’s Minuteman III fleet, in service since 1970, with the first of the new missiles due to become operational in the early 2030s. But it will take longer than that to build and activate the full complement of Sentinel missiles and the 450 hardened underground silos to house them, Ars reports.

Nowhere to put them... No one is ready to say when hundreds of new missile silos, dug from the windswept Great Plains, will be finished, how much they cost, or, for that matter, how many nuclear warheads each Sentinel missile could actually carry. The program’s cost has swelled from $78 billion to an official projection of $141 billion, but that figure is already out of date, as the Air Force announced last year that it would need to construct new silos for the Sentinel missile. The original plan was to adapt existing Minuteman III silos for the new weapons, but engineers determined that it would take too long and cost too much to modify the aging Minuteman facilities. Instead, the Air Force, in partnership with contractors and the US Army Corps of Engineers, will dig hundreds of new holes across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming. The new silos will include 24 new forward launch centers, three centralized wing command centers, and more than 5,000 miles of fiber connections to wire it all together, military and industry officials said.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Space One is now 0-for-3. Japan’s Space One said its Kairos small rocket self-destructed 69 seconds after liftoff on Thursday, failing to achieve the country’s first entirely commercial satellite launch for the third attempt in a row, Reuters reports. Three months after a failure of Japan’s flagship H3 rocket, the unsuccessful flight of the smaller Kairos launcher dealt a fresh blow to Japan’s efforts to establish domestic launch options and reduce its reliance on American rockets amid rising space security needs to counter China. Kairos measures about 59 feet (18 meters) long with three solid-fueled boost stages and a liquid-fueled upper stage to inject small satellites into low-Earth orbit. The rocket is capable of placing a payload of about 330 pounds (150 kilograms) into a Sun-synchronous orbit.

Accidental detonation... The Kairos rocket terminated its flight Thursday at an altitude of approximately 18 miles (29 kilometers) above the Pacific Ocean, just downrange from Space One’s spaceport on the southern coast of Honshu, the largest of Japan’s main islands. “No significant abnormalities were found in the flight or onboard equipment” before the self-destruction, Space One’s vice president, Nobuhiro Sekino, told a press conference, suggesting that the rocket’s autonomous flight termination system went wrong. This is a rare mode of failure in rocketry, but it has happened before. The first flight of Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket was terminated erroneously in 2017, despite no issues with the launch vehicle itself. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

PLD Space raises $209 million. PLD Space has raised 180 million euros ($209 million) to ramp up production of the Spanish startup’s Miura 5 launch vehicle, marking the largest funding round for a European space business announced this year, Space News reports. PLD said the Series C equity funding round is led by Japan’s Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, with co-investment from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, and the Spanish public funds management company Cofides. The startup has now raised more than 350 million euros ($400 million) to date. Miura 5 has not flown yet, but PLD says it is designed to place more than a metric ton (2,200 pounds) of payload mass into low-Earth orbit.

All about scaling... The fresh cash will support PLD’s “transition to commercial operations and the scaling of its industrial and launch capabilities,” the company said in a statement. “Miura 5 was designed to address a clear and growing capacity gap in the market, and this investment support strengthens our ability to transition into commercial operations,” said Ezequiel Sánchez, PLD Space’s executive president. “It accelerates the build‑out of the industrial and launch infrastructure required to deliver reliable access to space for an expanding pipeline of global customers.” (submitted by Leika and EllPeaTea)

MaiaSpace delays first launch. Another European launch startup, the French company MaiaSpace, has announced the first flight of its two-stage Maia rocket will take place in 2027, slipping from a previously expected late 2026 launch, European Spaceflight reports. MaiaSpace is a subsidiary of ArianeGroup, which builds Europe’s flagship Ariane 6 rocket. The Maia rocket will be partially reusable, with a recoverable first stage. Just two months ago, MaiaSpace said it was targeting an initial suborbital demonstration flight of the Maia rocket in late 2026.

Ensemble de lancement... On February 24, officials from MaiaSpace and the French space agency CNES gathered at the site of the former Soyuz launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, to sign a temporary occupancy agreement allowing MaiaSpace to begin dismantling Soyuz-specific infrastructure at the site. During the event, MaiaSpace officials revealed they expected to host the inaugural flight of Maia from the facility in 2027. When asked for comment by European Spaceflight, a representative explained that the company remained committed to launching its first rocket less than five years after the company’s creation in April 2022. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Korean company eyes launching from Canada. South Korean launch newcomer Innospace is exploring a planned spaceport in Nova Scotia, Canada, as a potential facility to expand operations to North America, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. The company, which has yet to successfully fly its Hanbit-Nano rocket, said on March 4 that it has reached a nonbinding, preliminary “letter of intent” with Canada’s Maritime Launch Services. Innospace said the letter of intent “establishes a strategic framework” for Korean and Canadian officials to “assess the technical, regulatory, and commercial feasibility” of launching Hanbit rockets from Nova Scotia. The first flight of the Hanbit-Nano rocket failed shortly after liftoff last year from a spaceport in Brazil, and Innospace already has preliminary agreements for potential launch sites in Europe and Australia.

Looking abroad... Several launch startups are looking at establishing additional launch sites beyond their initial operating locations. Firefly Aerospace is looking at Sweden, and Rocket Lab has already inaugurated a second launch site for its Electron rocket in Virginia after basing its first flights in New Zealand. Innospace is unique, though, in that the South Korean rocket company’s first launch pad is already halfway around the world from its home base. Meanwhile, Canada is investing in its own sovereign orbital launch capability. “We look forward to working with Innospace to evaluate how our strategic position on the Eastern Atlantic rim of North America can support their launch program while advancing reliable, repeatable access to orbit and strengthening Canada’s commercial launch capability,” said Stephen Matier, president and CEO of Maritime Launch Services.

Russia completes launch pad repairs. Late last year, a Soyuz rocket launched three astronauts to orbit from the Russian-run Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. But post-launch inspections revealed significant damage. A service structure underneath the rocket was unsecured during the launch of the three-man crew to the International Space Station. The structure fell into the launch pad’s flame trench, leaving the complex without the service cabin technicians use to work on the Soyuz rocket before liftoff. But Russia made quick repairs to the launch pad, the only site outfitted to launch Russian spacecraft to the ISS. Rockets will soon start flying from Pad 31 again, if all goes to plan, Space.com reports.

Restored to service... Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, announced Tuesday that the launch pad has been repaired. More than 150 employees from the agency’s Center for Operation of Space Ground-Based Infrastructure and representatives from four contractors have wrapped up work at the damaged launch pad. Roscosmos said 2,350 square meters of structures were prepared and painted, and more than 250 linear meters of welds were completed during the repair. Meanwhile, the head of the Roscosmos ground infrastructure division told a Russian TV channel in January that “multiple members” of the launch pad team were under criminal investigation after leaving the service structure unsecured during the November launch, according to Russian space reporter Anatoly Zak. The first launch from the restored pad is scheduled for March 22, when a Soyuz rocket will boost a Progress supply ship to the ISS. A Soyuz crew launch will follow this summer.

SpaceX price hike. SpaceX recently increased launch prices from $70 million to $74 million for a dedicated Falcon 9 ride, and $6,500 per kilogram to $7,000 per kilogram for a rideshare slot, Payload reports. The company has long signaled a steady pace of price bumps, so the move does not come as a surprise. Nonetheless, the increase (along with the lack of real alternatives) highlights a tough truth in the industry: Access to orbit has gotten significantly more expensive in recent years despite all the hoopla and hopium of falling launch prices.

Keeping up… The price of a dedicated launch on a Falcon 9 has risen about 20 percent since 2021, in line with US inflation. A rideshare slot, on the other hand, now costs about 40 percent more than it did in 2021, doubling the rate of inflation, according to Payload. Rideshare pricing is the far more important number to track here. Without a price-competitive alternative, the broader space startup community has relied almost exclusively on Falcon 9 Transporter and Bandwagon missions to get to space over the last five years. Ars has previously reported on how NASA pays more for launch services than it did 30 years ago, a trend partly driven by the agency’s requirement for dedicated launches for many of its robotic science missions.

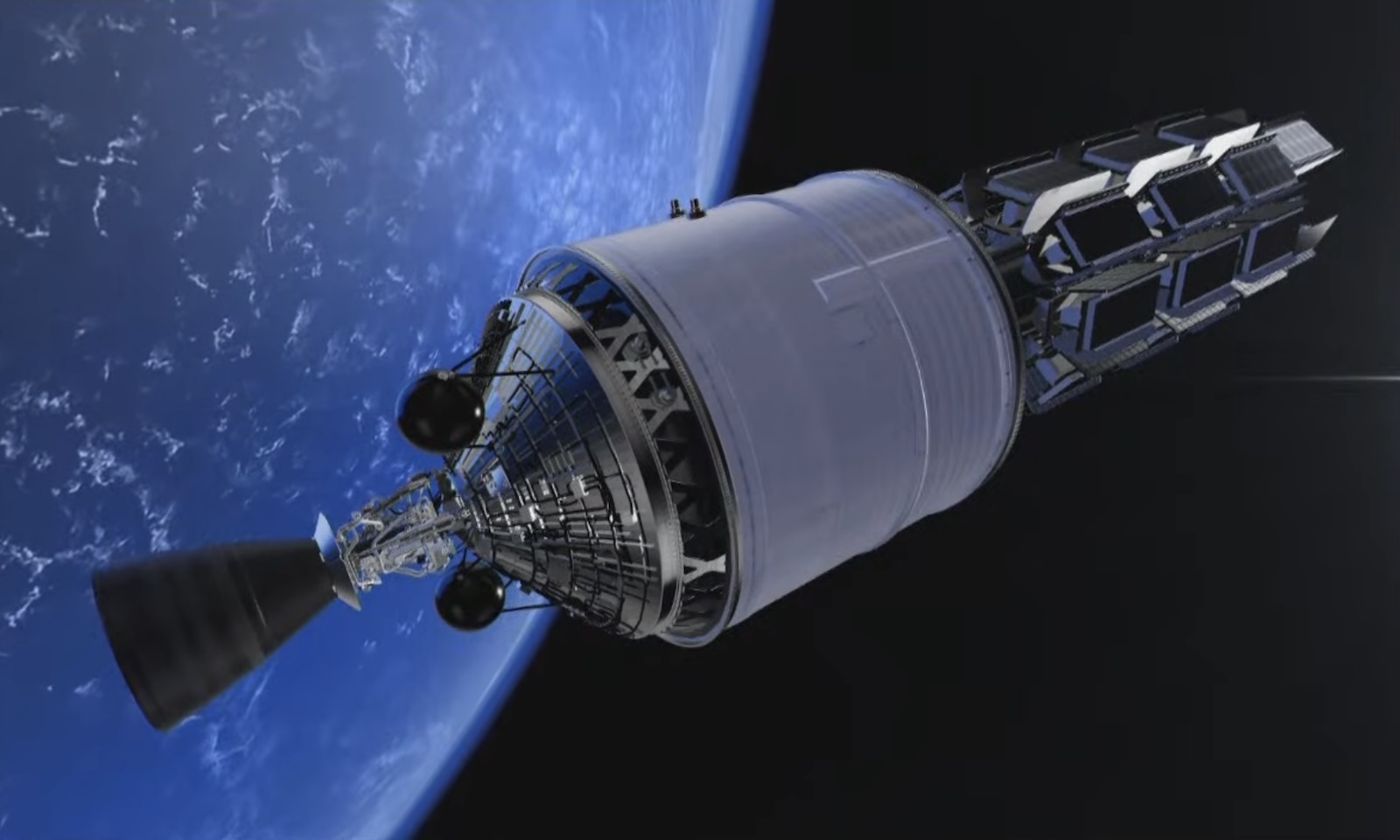

NASA aims for standardized SLS rocket. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman announced sweeping changes to the Artemis program on February 27, including an increased cadence of missions and cancellation of an expensive rocket stage, Ars reports. The upheaval comes as NASA has struggled to fuel the massive Space Launch System rocket for the upcoming Artemis II lunar mission and Isaacman has sought to revitalize an agency that has moved at a glacial pace on its deep space programs. There is growing concern that, absent a shake-up, China’s rising space program will land humans on the Moon before NASA can return there this decade with Artemis.

CU later, EUS… “NASA must standardize its approach, increase flight rate safely, and execute on the president’s national space policy,” Isaacman said. “With credible competition from our greatest geopolitical adversary increasing by the day, we need to move faster, eliminate delays, and achieve our objectives.” The announced changes to the Artemis program include the cancellation of the Exploration Upper Stage and Block IB upgrade for SLS rocket, and future SLS missions, starting with Artemis IV, will use a “standardized” commercial upper stage. Artemis III will no longer land on the Moon. Instead, the Orion spacecraft will launch on SLS and dock with SpaceX’s Starship and/or Blue Origin’s Blue Moon landers in low-Earth orbit.

NASA favors ULA upper stage. United Launch Alliance’s Centaur V upper stage, used on the company’s Vulcan rocket, will replace the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) on SLS missions beginning with Artemis IV, Bloomberg reports. ULA, a 50-50 joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin, also built the interim upper stages flying on the Artemis I, II, and III missions. Those stages were based on designs used for ULA’s now-retired Delta IV Heavy rocket. With that production line shut down, ULA will now provide Centaur Vs to NASA. This means Boeing, which was on contract to develop the EUS, will still have a role in supplying upper stages for the SLS rocket. Boeing is also the prime contractor for the rocket’s massive core stage.

Building on a legacy… The Centaur V upper stage is the latest version of a design that dates back to the 1960s. Centaurs began flying in 1962, and the Centaur V is the most powerful variant, with a wider diameter and two hydrogen-fueled RL10 engines. The Centaur V still uses the ultra-thin, pressure-stabilized stainless steel structure used on all Centaur upper stages. The Centaur has a reliable track record, and the Centaur V’s predecessor, the Centaur III, was human-rated for launches of Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule.

Artemis II helium issue fixed. NASA has fixed the problem that forced it to remove the rocket for the Artemis II mission from its launch pad last month, but it will be a couple of weeks before officials are ready to move the vehicle back into the starting blocks at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Ars reports. Ground teams moved the SLS rocket back to the Vehicle Assembly Building last month to repair an issue with the upper stage’s helium system. Inspections revealed that a seal in the quick disconnect, through which helium flows from ground systems into the rocket, was obstructing the pathway, according to NASA. “The team removed the quick disconnect, reassembled the system, and began validating the repairs to the upper stage by running a reduced flow rate of helium through the mechanism to ensure the issue was resolved,” NASA said in an update posted Tuesday.

Targeting April 1… NASA is not expected to return the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft to the launch pad until later this month. Inside the VAB, technicians will complete several other tasks to “refresh” the rocket for the next series of launch opportunities. NASA has not said whether the launch team will conduct another countdown rehearsal after it returns to Launch Complex 39B at Kennedy. The first of five launch opportunities in early April is on April 1, with a two-hour launch window opening at 6: 24 pm EDT (22: 24 UTC). There are additional launch dates available on April 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Next three launches

March 7: Falcon 9 | Starlink 17-18 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 10: 58 UTC

March 10: Alpha | Stairway to Seven | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 00: 50 UTC

March 10: Falcon 9 | EchoStar XXV | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 03: 14 UTC

Rocket Report: SpaceX launch prices are going up; Russia fixes broken launch pad Read More »