Under pressure after setbacks, SpaceX’s huge rocket finally goes the distance

The ship made it all the way through reentry, turned to a horizontal position to descend through scattered clouds, then relit three of its engines to flip back to a vertical orientation for the final braking maneuver before splashdown.

Things to improve on

There are several takeaways from Tuesday’s flight that will require some improvements to Starship, but these are more akin to what officials might expect from a rocket test program and not the catastrophic failures of the ship that occurred earlier this year.

One of the Super Heavy booster’s 33 engines prematurely shut down during ascent. This has happened before, and while it didn’t affect the booster’s overall performance, engineers will investigate the failure to try to improve the reliability of SpaceX’s Raptor engines, each of which can generate more than a half-million pounds of thrust.

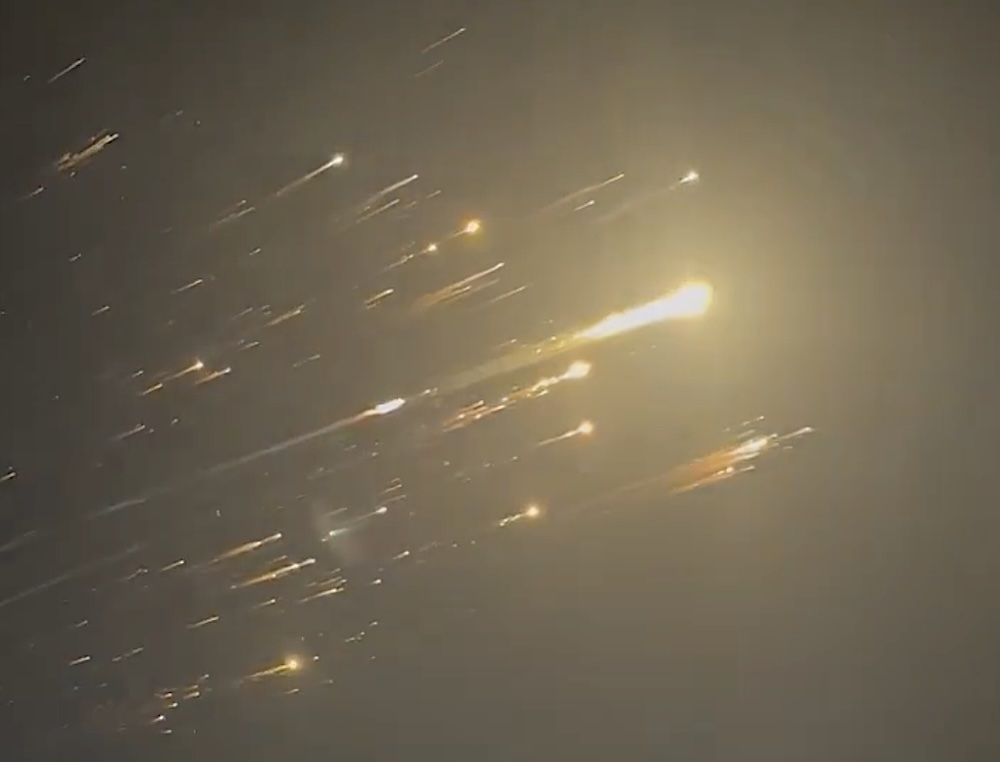

Later in the flight, cameras pointed at one of the ship’s rear flaps showed structural damage to the back of the wing. It wasn’t clear what caused the damage, but super-heated plasma burned through part of the flap as the ship fell deeper into the atmosphere. Still, the flap remained largely intact and was able to help control the vehicle through reentry and splashdown.

“We’re kind of being mean to this Starship a little bit,” Huot said on SpaceX’s live webcast. “We’re really trying to put it through the paces and kind of poke on what some of its weak points are.”

Small chunks of debris were also visible peeling off the ship during reentry. The origin of the glowing debris wasn’t immediately clear, but it may have been parts of the ship’s heat shield tiles. On this flight, SpaceX tested several different tile designs, including ceramic and metallic materials, and one tile design that uses “active cooling” to help dissipate heat during reentry.

A bright flash inside the ship’s engine bay during reentry also appeared to damage the vehicle’s aft skirt, the stainless steel structure that encircles the rocket’s six main engines.

“That’s not what we want to see,” Huot said. “We just saw some of the aft skirt just take a hit. So we’ve got some visible damage on the aft skirt. We’re continuing to reenter, though. We are intentionally stressing the ship as we go through this, so it is not guaranteed to be a smooth ride down to the Indian Ocean.

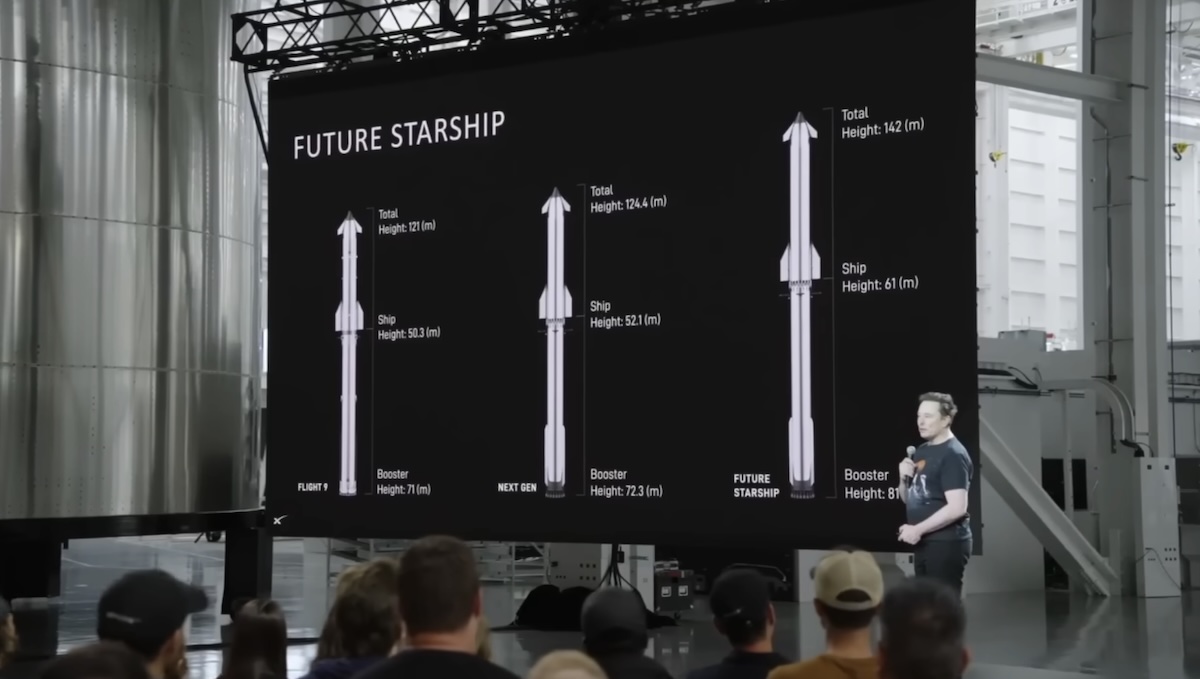

“We’ve removed a bunch of tiles in kind of critical places across the vehicle, so seeing stuff like that is still valuable to us,” he said. “We are trying to kind of push this vehicle to the limits to learn what its limits are as we design our next version of Starship.”

Shana Diez, a Starship engineer at SpaceX, perhaps summed up Tuesday’s results best on X: “It’s not been an easy year but we finally got the reentry data that’s so critical to Starship. It feels good to be back!”

Under pressure after setbacks, SpaceX’s huge rocket finally goes the distance Read More »