Rocket Report: Chinese rockets fail twice in 12 hours; Rocket Lab reports setback

Another partially reusable Chinese rocket, the Long March 12B, is nearing its first test flight.

An Archimedes engine for Rocket Lab’s Neutron rocket is test-fired at Stennis Space Center, Mississippi. Credit: Rocket Lab

Welcome to Edition 8.26 of the Rocket Report! The past week has been one of advancements and setbacks in the rocket business. NASA rolled the massive rocket for the Artemis II mission to its launch pad in Florida, while Chinese launchers suffered back-to-back failures within a span of approximately 12 hours. Rocket Lab’s march toward a debut of its new Neutron launch vehicle in the coming months may have stalled after a failure during a key qualification test. We cover all this and more in this week’s Rocket Report.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Australia invests in sovereign launch. Six months after its first orbital rocket cleared the launch tower for just 14 seconds before crashing back to Earth, Gilmour Space Technologies has secured 217 million Australian dollars ($148 million) in funding that CEO Adam Gilmour says finally gives Australia a fighting chance in the global space race, the Sydney Morning Herald reports. The funding round, led by the federal government’s National Reconstruction Fund Corporation and superannuation giant Hostplus with $75 million each, makes the Queensland company Australia’s newest unicorn—a fast-growth start-up valued at more than $1 billion—and one of the country’s most heavily backed private technology ventures.

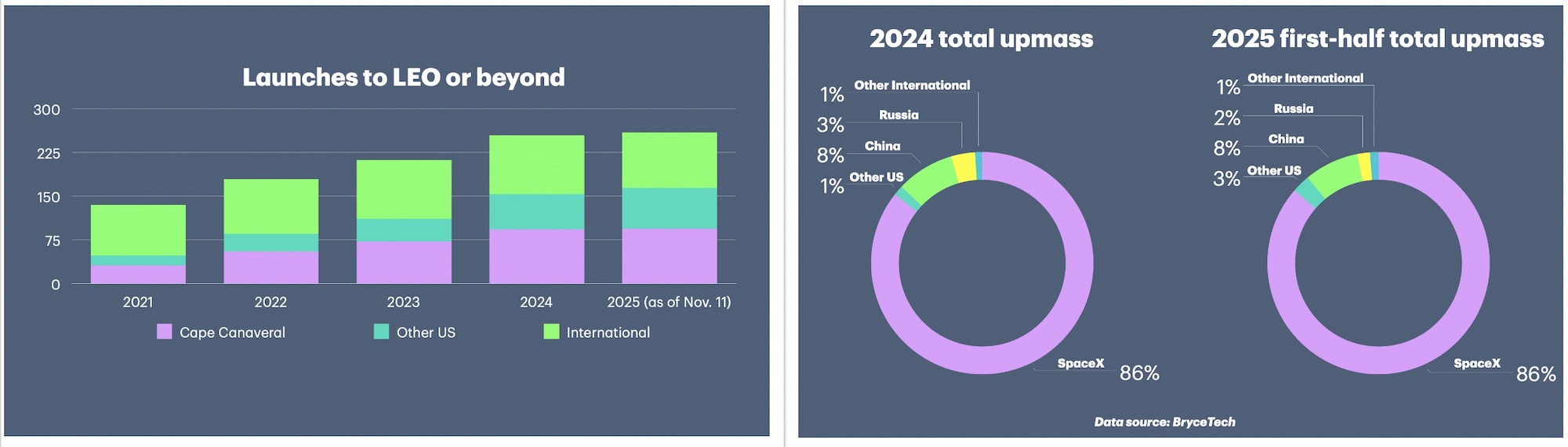

Homegrown rocket… “We’re a rocket company that has never had access to the capital that our American competitors have,” Gilmour told the newspaper. “This is the first raise where I’ve actually raised a decent amount of capital compared to the rest of the world.” The investment reflects growing concern about Australia’s reliance on foreign launch providers—predominantly Elon Musk’s SpaceX—to put government, defense, and commercial satellites into orbit. With US launch queues stretching beyond two years and geopolitical tensions reshaping access to space infrastructure, Canberra has identified sovereign launch capability as a strategic priority. Gilmour’s first Eris rocket lifted off from the Bowen Orbital Spaceport in North Queensland on July 30 last year. It achieved 14 seconds of flight before falling back to the ground, a result Gilmour framed as a partial success in an industry where first launches routinely fail.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Isar Aerospace postpones test flight. Isar Aerospace scrubbed a potential January 21 launch of its Spectrum rocket to address a technical fault, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. Hours before the launch window was set to open, the German company said that it was addressing “an issue with a pressurization valve.” A valve issue was one of the factors that caused a Spectrum to crash moments after liftoff on Isar’s first test flight last year. “The teams are currently assessing the next possible launch opportunities and a new target date will be announced shortly,” the company wrote in a post on its website. The Spectrum rocket, designed to haul cargoes of up to a metric ton (2,200 pounds) to low-Earth orbit, is awaiting liftoff from Andøya Spaceport in Norway.

Geopolitics at play... The second launch of Isar’s Spectrum rocket comes at a time when Europe’s space industry looks to secure the continent’s sovereignty in spaceflight. European satellites are no longer able to launch on Russian rockets, and the continent’s leaders don’t have much of an appetite to turn to US rockets amid strained trans-Atlantic relations. Europe’s satellite industry is looking for more competition for the Ariane 6 and Vega C rockets developed by ArianeGroup and Avio, and Isar Aerospace appears to be best positioned to become a new entrant in the European launch market. “I’m well aware that it would be really good for us Europeans to get this one right,” said Daniel Metzler, Isar’s co-founder and CEO.

A potential buyer for Orbex? UK-based rocket builder Orbex has signed a letter of intent to sell its business to European space logistics startup The Exploration Company, European Spaceflight reports. Orbex was founded in 2015 and is developing a small launch vehicle called Prime. The company also began work on a larger medium-lift launch vehicle called Proxima in December 2024. On Wednesday, Orbex published a brief press release stating that a letter of intent had been signed and that negotiations had begun. The company added that all details about the transaction remain confidential at this stage.

Time’s up... A statement from Orbex CEO Phil Chambers suggests that the company’s financial position factored into its decision to pursue a buyer. “Our Series D fundraising could have led us in many directions,” said Chambers. “We believe this opportunity plays to the strengths of both businesses, and we look forward to sharing more when the time is right.” The Exploration Company, headquartered near Munich, Germany, is developing a reusable space capsule to ferry cargo to low-Earth orbit and a high-thrust reusable rocket engine. It is one of the most well-financed space startups in Europe. Orbex is one of five launch startups in Europe selected by the European Space Agency last year to compete in the European Launcher Challenge and receive funding from ESA member states. But the UK company’s financial standing is in question. Orbex’s Danish subsidiary is filing for bankruptcy, and its main UK entity is overdue in filing its 2024 financial accounts. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

A bad day for Chinese rockets. China suffered a pair of launch failures January 16, seeing the loss of a classified Shijian satellite and the failed first launch of the Ceres-2 rocket, Space News reports. The first of the two failures involved the attempted launch of a Shijian military satellite aboard a Long March 3B rocket from the Xichang launch base in southwestern China. The Shijian 32 satellite was likely heading for a geostationary transfer orbit, but a failure of the Long March 3B’s third stage doomed the mission. The Long March 3B is one of China’s most-flown rockets, and this was the first failure of a Long March 3-series vehicle since 2020, ending a streak of 50 consecutive successful flights of the rocket.

And then… Less than 12 hours later, another Chinese rocket failed on its climb to orbit. This launch, using a Ceres-2 rocket, originated from the Jiuquan space center in northwestern China. It was the first flight of the Ceres-2, a larger variant of the light-class Ceres-1 rocket developed and operated by a Chinese commercial startup named Galactic Energy. Chinese officials did not disclose the payloads lost on the Ceres-2 rocket.

Neutron in neutral. Rocket Lab suffered a structural failure of the Neutron rocket’s Stage 1 tank during testing, setting back efforts to get to the inaugural flight for the partially reusable launcher, Aviation Week & Space Technology reports. The mishap occurred during a hydrostatic pressure trial, the company said Wednesday. “There was no significant damage to the test structure or facilities,” Rocket Lab added. Rocket Lab last year pushed the first Neutron mission from 2025 to 2026, citing the volume of testing ahead. The US-based company said it is now analyzing what transpired to determine the impact on Neutron launch plans. Rocket Lab said it would provide an update during its next quarterly financials, due in a few weeks.

Where to go from here?… The Neutron rocket is designed to catapult Rocket Lab into more direct competition with legacy rocket companies like SpaceX and United Launch Alliance. “The next Stage 1 tank is already in production, and Neutron’s development campaign continues,” the company said. Setbacks like this one are to be expected during the development of new rockets. Rocket Lab has publicized aggressive, or aspirational, launch schedules for the first Neutron rocket, so it’s likely the company will hang onto its projection of a debut launch in 2026, at least for now. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

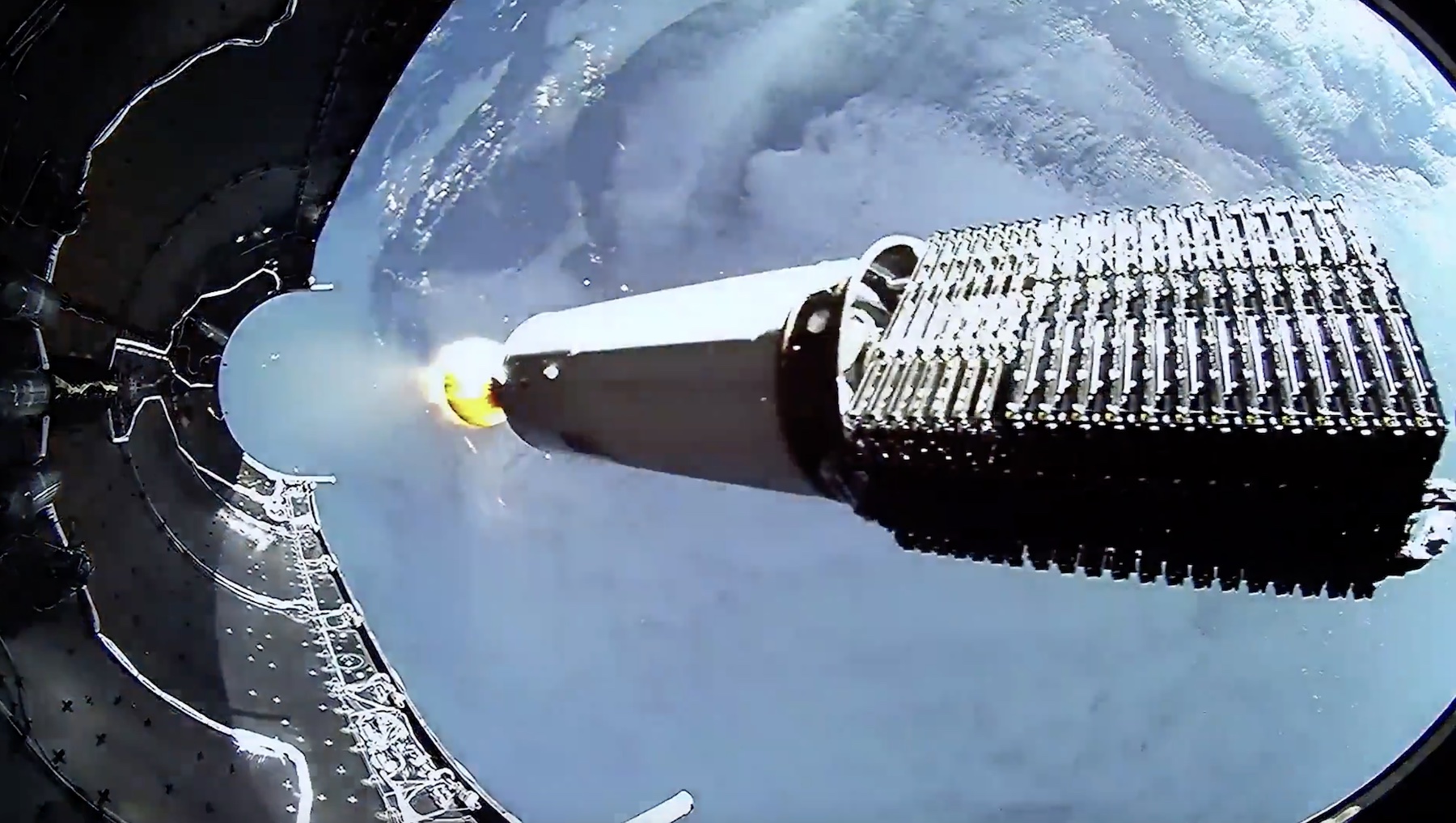

Falcon 9 launches NRO spysats. SpaceX executed a late night Falcon 9 launch from Vandenberg Space Force Base on January 16, carrying an undisclosed number of intelligence-gathering satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office, Spaceflight Now reports. The mission, NROL-105, hauled a payload of satellites heading to low-Earth orbit, which are believed to be Starshield, a government variant of the Starlink satellites. “Today’s mission is the twelfth overall launch of the NRO’s proliferated architecture and first of approximately a dozen NRO launches scheduled throughout 2026 consisting of proliferated and national security missions,” the NRO said in a post-launch statement.

Mysteries abound… A public accounting of the agency’s proliferated constellation suggests it now numbers nearly 200 satellites with the ability to rapidly image locations around the world. The NRO has dozens more satellites serving other functions. “Having hundreds of NRO satellites on orbit is critical to supporting our nation and its partners,” the agency said in a statement. “This growing constellation enhances mission resilience and capability through reduced revisit times, improved persistent coverage, and accelerated processing and delivery of critical data.” What was unusual about the January 16 mission is it may have only carried two satellites, well short of the 20-plus Starshield satellites launched on most previous Falcon 9 launches, according to Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist and expert tracker of global space launch activity.

Long March 12B hot-fired at Jiuquan. China’s main space contractor performed a static fire test of a new reusable Long March rocket Friday, paving the way for a test flight, Space News reports. The test-firing of the Long March 12B rocket’s first stage engines occurred on a launch pad at the Dongfeng Commercial Space Innovation Test Zone at Jiuquan spaceport in northwestern China. The mere existence of the Long March 12B rocket was not publicly known until recently. The new rocket was developed by a subsidiary of the state-owned China Aerospace Science Technology Corporation, with the capacity to carry a payload of 20 metric tons to low-Earth orbit in expendable mode. It’s unknown if the first Long March 12B test flight will include a booster landing attempt.

Another one… The Long March 12B has a reusable first stage with landing legs, similar to the recovery architecture of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. The booster is designed to land downrange at a recovery zone in the Gobi Desert. The Long March 12B is the latest in a line of partially reusable Chinese rockets to reach the launch pad, following soon after the debut launches of the Long March 12A and Zhuque 3 rocket last month. Several more companies in China are working on their own reusable boosters. Of them all, the Long March 12B appears to be the closest to a clone of SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Like the Falcon 9, the Long March 12B will have nine kerosene-fueled first stage engines and a single kerosene-fueled upper stage engine. Chinese officials have not announced when the Long March 12B will launch.

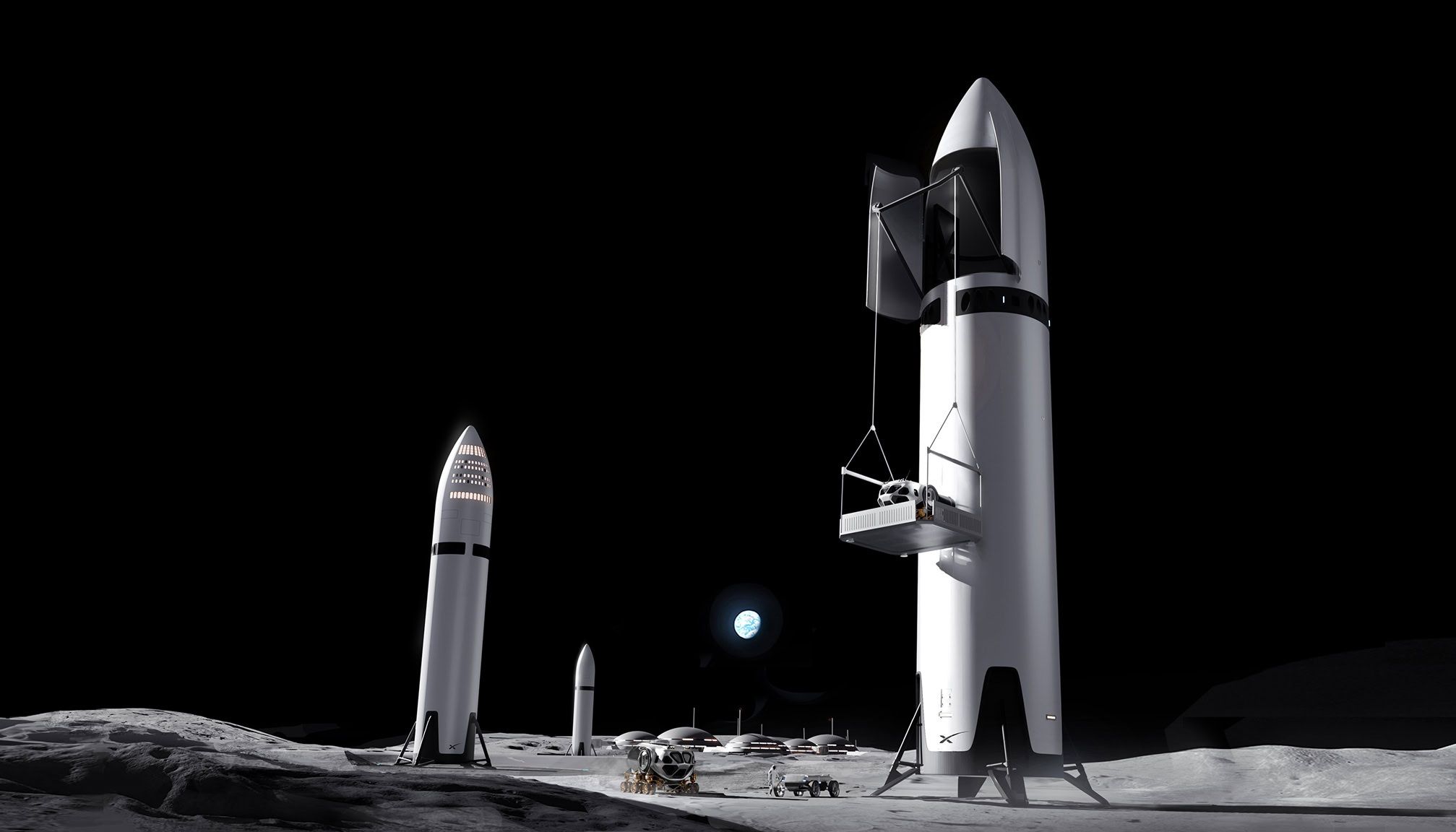

Artemis II rolls to the launch pad. Preparations for the first human spaceflight to the Moon in more than 50 years took a big step forward last weekend with the rollout of the Artemis II rocket to its launch pad, Ars reports. The rocket reached a top speed of just 1 mph on the four-mile, 12-hour journey from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Complex 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. At the end of its nearly 10-day tour through cislunar space, the Orion capsule on top of the rocket will exceed 25,000 mph as it plunges into the atmosphere to bring its four-person crew back to Earth.

Key test ahead… “This is the start of a very long journey,” said NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman. “We ended our last human exploration of the Moon on Apollo 17.” The Artemis II mission will set several notable human spaceflight records. Astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen will travel farther from Earth than any human in history as they travel beyond the far side of the Moon. They won’t land. That distinction will fall to the next mission in line in NASA’s Artemis program. This will be the first time astronauts have flown on the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft. The launch window opens February 6, but the exact date of Artemis II’s liftoff will be determined by the outcome of a critical fueling test of the SLS rocket scheduled for early February.

Blue Origin confirms rocket reuse plan. Blue Origin confirmed Thursday that the next launch of its New Glenn rocket will carry a large communications satellite into low-Earth orbit for AST SpaceMobile, Ars reports. The rocket will launch the next-generation Block 2 BlueBird satellite “no earlier than late February” from Launch Complex 36 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. However, the update from Blue Origin appears to have buried the real news toward the end: “The mission follows the successful NG-2 mission, which included the landing of the ‘Never Tell Me The Odds’ booster. The same booster is being refurbished to power NG-3,” the company said.

Impressive strides… The second New Glenn mission launched on November 13, just 10 weeks ago. If the company makes the late-February target for the next mission—and Ars was told last week to expect the launch to slip into March—it will represent a remarkably short turnaround for an orbital booster. By way of comparison, SpaceX did not attempt to refly the first Falcon 9 booster it landed in December 2015. Instead, initial tests revealed that the vehicle’s interior had been somewhat torn up. It was scrapped and inspected closely so that engineers could learn from the wear and tear.

Next three launches

Jan. 25: Falcon 9 | Starlink 17-20 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 15: 17 UTC

Jan. 26: Falcon 9 | GPS III SV09 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 04: 46 UTC

Jan. 26: Long March 7A | Unknown Payload | Wenchang Space Launch Site, China | 21: 00 UTC

Rocket Report: Chinese rockets fail twice in 12 hours; Rocket Lab reports setback Read More »