Rocket Report: New delay for Europe’s reusable rocket; SpaceX moves in at SLC-37

Canada is the only G7 nation without a launch program. Quebec wants to do something about that.

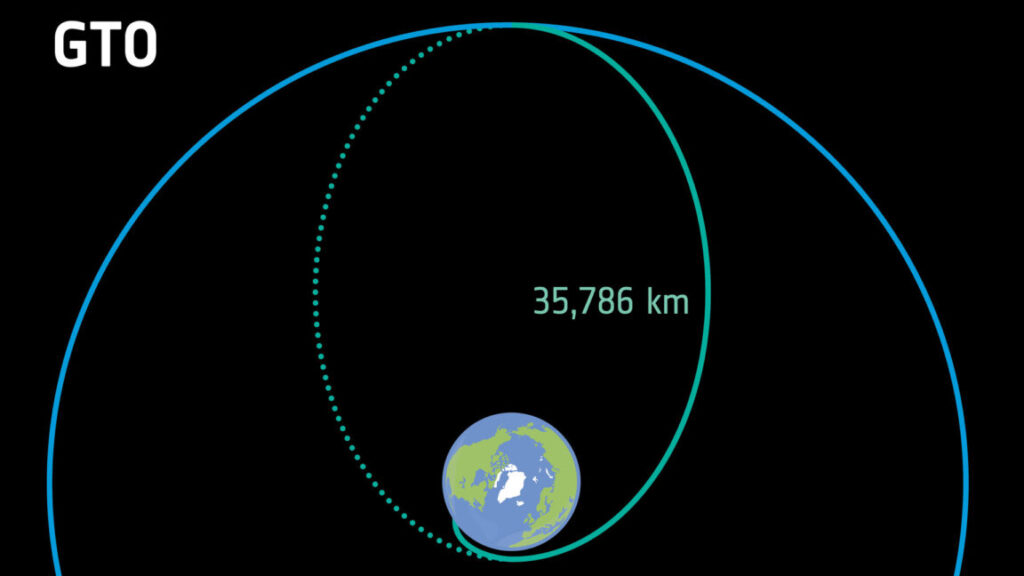

This graphic illustrates the elliptical shape of a geosynchronous transfer orbit in green, and the circular shape of a geosynchronous orbit in blue. In a first, SpaceX recently de-orbited a Falcon 9 upper stage from GTO after deploying a communications satellite. Credit: European Space Agency

Welcome to Edition 7.48 of the Rocket Report! The shock of last week’s public spat between President Donald Trump and SpaceX founder Elon Musk has worn off, and Musk expressed regret for some of his comments going after Trump on social media. Musk also backtracked from his threat to begin decommissioning the Dragon spacecraft, currently the only way for the US government to send people to the International Space Station. Nevertheless, there are many people who think Musk’s attachment to Trump could end up putting the US space program at risk, and I’m not convinced that danger has passed.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Quebec invests in small launch company. The government of Quebec will invest CA$10 million ($7.3 million) into a Montreal-area company that is developing a system to launch small satellites into space, The Canadian Press reports. Quebec Premier François Legault announced the investment into Reaction Dynamics at the company’s facility in Longueuil, a Montreal suburb. The province’s economy minister, Christine Fréchette, said the investment will allow the company to begin launching microsatellites into orbit from Canada as early as 2027.

Joining its peers … Canada is the only G7 nation without a domestic satellite launch capability, whether it’s through an independent national or commercial program or through membership in the European Space Agency, which funds its own rockets. The Canadian Space Agency has long eschewed any significant spending on developing a Canadian satellite launcher, and a handful of commercial launch startups in Canada haven’t gotten very far. Reaction Dynamics was founded in 2017 by Bachar Elzein, formerly a researcher in multiphase and reactive flows at École Polytechnique de Montréal, where he specialized in propulsion and combustion dynamics. Reaction Dynamic plans to launch its first suborbital rocket later this year, before attempting an orbital flight with its Aurora rocket as soon as 2027. (submitted by Joey S-IVB)

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Another year, another delay for Themis. The European Space Agency’s Themis program has suffered another setback, with the inaugural flight of its reusable booster demonstrator now all but certain to slip to 2026, European Spaceflight reports. It has been nearly six years since the European Space Agency kicked off the Themis program to develop and mature key technologies for future reusable rocket stages. Themis is analogous to SpaceX’s Grasshopper reusable rocket prototype tested more than a decade ago, with progressively higher hop tests to demonstrate vertical takeoff and vertical landing techniques. When the program started, an initial hop test of the first Themis demonstrator was expected to take place in 2022.

Tethered to terra firma … ArianeGroup, which manufactures Europe’s Ariane rockets, is leading the Themis program under contract to ESA, which recently committed an additional 230 million euros ($266 million) to the effort. This money is slated to go toward development of a single-engine variant of the Themis program, continued development of the rocket’s methane-fueled engine, and upgrades to a test stand at ArianeGroup’s propulsion facility in Vernon, France. Two months ago, an official update on the Themis program suggested the first Themis launch campaign would begin before the end of the year. Citing sources close to the program, European Spaceflight reports the first Themis integration tests at the Esrange Space Center in Sweden are now almost certain to slip from late 2025 to 2026.

French startup tests a novel rocket engine. While Europe’s large government-backed rocket initiatives face delays, the continent’s space industry startups are moving forward on their own. One of these companies, a French startup named Alpha Impulsion, recently completed a short test-firing of an autophage rocket engine, European Spaceflight reports. These aren’t your normal rocket engines that burn conventional kerosene, methane, or hydrogen fuel. An autophage engine literally consumes itself as it burns, using heat from the combustion process to melt its plastic fuselage and feed the molten plastic into the combustion chamber in a controlled manner. Alpha Impulsion called the May 27 ground firing a successful test of the “largest autophage rocket engine in the world.”

So, why hasn’t this been done before? … The concept of a self-consuming rocket engine sounds like an idea that’s so crazy it just might work. But the idea remained conceptual from when it was first patented in 1938 until an autophage engine was fired in a controlled manner for the first time in 2018. The autophage design offers several advantages, including its relative simplicity compared to the complex plumbing of liquid and hybrid rockets. But there are serious challenges associated with autophage engines, including how to feed molten fuel into the combustion chamber and how to scale it up to be large enough to fly on a viable rocket. (submitted by trimeta and EllPeaTea)

Rocket trouble delays launch of private crew mission. A propellant leak in a Falcon 9 booster delayed the launch of a fourth Axiom Space private astronaut mission to the International Space Station this week, Space News reports. SpaceX announced the delay Tuesday, saying it needed more time to fix a liquid oxygen leak found in the Falcon 9 booster during inspections following a static-fire test Sunday. “Once complete–and pending Range availability–we will share a new launch date,” the company stated. The Ax-4 mission will ferry four commercial astronauts, led by retired NASA commander Peggy Whitson, aboard a Dragon spacecraft to the ISS for an approximately 14-day stay. Whitson will be joined by crewmates from India, Poland, and Hungary.

Another problem, too … While SpaceX engineers worked on resolving the propellant leak on the ground, a leak of another kind in orbit forced officials to order a longer delay to the Ax-4 mission. In a statement Thursday, NASA said it is working with the Russian space agency to understand a “new pressure signature” in the space station’s Russian service module. For several years, ground teams have monitored a slow air leak in the aft part of the service module, and NASA officials have identified it as a safety risk. NASA’s statement on the matter was vague, only saying that cosmonauts on the station recently inspected the module’s interior surfaces and sealed additional “areas of interest.” The segment is now holding pressure, according to NASA. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

SpaceX tries something new with Falcon 9. With nearly 500 launches under its belt, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket isn’t often up to new tricks. But the company tried something new following a launch June 7 with a radio broadcasting satellite for SiriusXM. The Falcon 9’s upper stage placed the SXM-10 satellite into an elongated, high-altitude transfer orbit, as is typical for payloads destined to operate in geosynchronous orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator. When a rocket releases a satellite in this type of high-energy orbit, the upper stage has usually burned almost all of its propellant, leaving little fuel left over to steer itself back into Earth’s atmosphere for a destructive reentry. This means these upper stages often remain in space for decades, becoming a piece of space junk transiting across the orbits of many other satellites.

Now, a solution … SpaceX usually deorbits rockets after they deploy payloads like Starlink satellites into low-Earth orbit, but deorbiting a rocket from a much higher geosynchronous transfer orbit is a different matter. “Last week, SpaceX successfully completed a controlled deorbit of the SiriusXM-10 upper stage after GTO payload deployment,” wrote Jon Edwards, SpaceX’s vice president of Falcon and Dragon programs. “While we routinely do controlled deorbits for LEO stages (e.g., Starlink), deorbiting from GTO is extremely difficult due to the high energy needed to alter the orbit, making this a rare and remarkable first for us. This was only made possible due to the hard work and brilliance of the Falcon GNC (guidance, navigation, and control) team and exemplifies SpaceX’s commitment to leading in both space exploration and public safety.”

New Glenn gets a tentative launch date. Five months have passed since Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket made its mostly successful debut in January. At one point the company targeted “late spring” for the second launch of the rocket. However, on Monday, Blue Origin’s CEO, Dave Limp, acknowledged on social media that the rocket’s next flight will now no longer take place until at least August 15, Ars reports. Although he did not say so, this may well be the only other New Glenn launch this year. The mission, with an undesignated payload, will be named “Never Tell Me the Odds,” due to the attempt to land the booster. “One of our key mission objectives will be to land and recover the booster,” Limp wrote. “This will take a little bit of luck and a lot of excellent execution. We’re on track to produce eight GS2s [second stages] this year, and the one we’ll fly on this second mission was hot-fired in April.”

Falling short … Before 2025 began, Limp set expectations alongside Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos: New Glenn would launch eight times this year. That’s not going to happen. It’s common for launch companies to take a while ramping up the flight rate for a new rocket, but Bezos told Ars in January that his priority for Blue Origin this year was to hit a higher cadence with New Glenn. Elon Musk’s rift with President Donald Trump could open a pathway for Blue Origin to capture more government business if the New Glenn rocket is able to establish a reliable track record. Meanwhile, Limp told Blue Origin employees last month that Jarrett Jones, the manager running the New Glenn program, is taking a sabbatical. Although it appears Jones’ leave may have been planned, the timing is curious.

Making way for Starship at Cape Canaveral. The US Air Force is moving closer to authorizing SpaceX to move into one of the largest launch pads at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, with plans to use the facility for up to 76 launches of the company’s Starship rocket each year, Ars reports. A draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) released by the Department of the Air Force, which includes the Space Force, found SpaceX’s planned use of Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral would have no significant negative impacts on local environmental, historical, social, and cultural interests. The Air Force also found SpaceX’s plans at SLC-37 will have no significant impact on the company’s competitors in the launch industry.

Bringing the rumble … SLC-37 was the previous home to United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV rocket, which last flew from the site in April 2024, a couple of months after the military announced SpaceX was interested in using the launch pad. While it doesn’t have a lease for full use of the launch site, SpaceX has secured a “right of limited entry” from the Space Force to begin preparatory work. This included the explosive demolition of the launch pad’s Delta IV-era service towers and lightning masts Thursday, clearing the way for eventual construction of two Starship launch towers inside the perimeter of SLC-37. The new Starship launch towers at SLC-37 will join other properties in SpaceX’s Starship empire, including nearby Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, and SpaceX’s privately owned facility at Starbase, Texas.

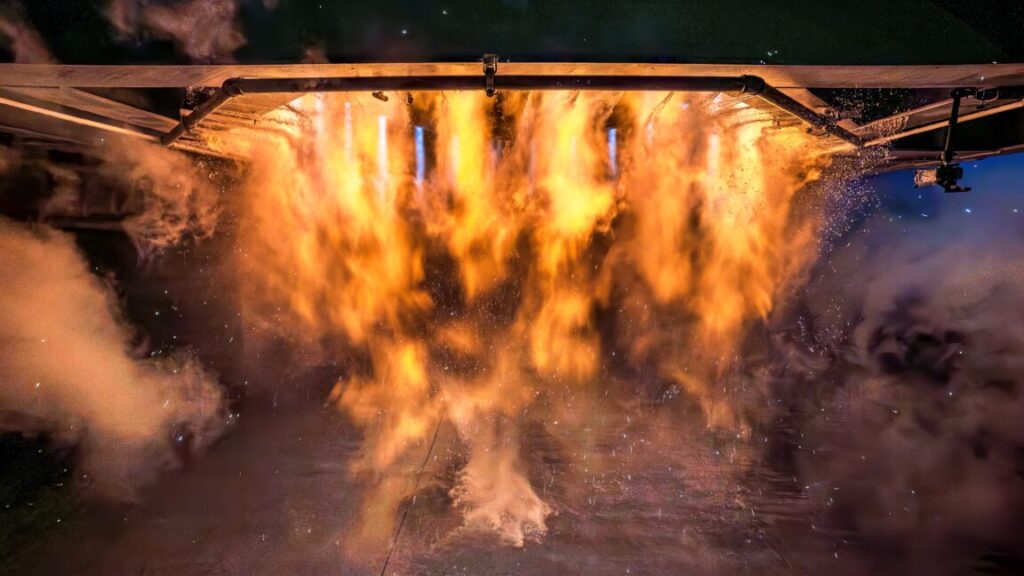

Preps continue for Starship Flight 10. Meanwhile, at Starbase, SpaceX is moving forward with preparations for the next Starship test flight, which could happen as soon as next month following three consecutive flights that fell short of expectations. This next launch will be the 10th full-scale test flight of Starship. Last Friday, June 6, SpaceX test-fired the massive Super Heavy booster designated to launch on Flight 10. All 33 of its Raptor engines ignited on the launch pad in South Texas. This is a new Super Heavy booster. On Flight 9 last month, SpaceX flew a reused Super Heavy booster that launched and was recovered on a flight in January.

FAA signs off on SpaceX investigation … The Federal Aviation Administration said Thursday it has closed the investigation into Starship Flight 8 in March, which spun out of control minutes after liftoff, showering debris along a corridor of ocean near the Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. “The FAA oversaw and accepted the findings of the SpaceX-led investigation,” an agency spokesperson said. “The final mishap report cites the probable root cause for the loss of the Starship vehicle as a hardware failure in one of the Raptor engines that resulted in inadvertent propellant mixing and ignition. SpaceX identified eight corrective actions to prevent a reoccurrence of the event.” SpaceX implemented the corrective actions prior to Flight 9 last month, when Starship progressed further into its mission before starting to tumble in space. It eventually reentered the atmosphere over the Indian Ocean. The FAA has mandated a fresh investigation into Flight 9, and that inquiry remains open.

Next three launches

June 13: Falcon 9 | Starlink 12-26 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 15: 21 UTC

June 14: Long March 2D | Unknown Payload | Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, China | 07: 55 UTC

June 16: Atlas V | Project Kuiper KA-02| Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 17: 25 UTC

Rocket Report: New delay for Europe’s reusable rocket; SpaceX moves in at SLC-37 Read More »