With Gateway likely gone, where will lunar landers rendezvous with Orion?

Drink up, astrodynamicists!

“We will challenge every requirement, clear every obstacle, delete every blocker.”

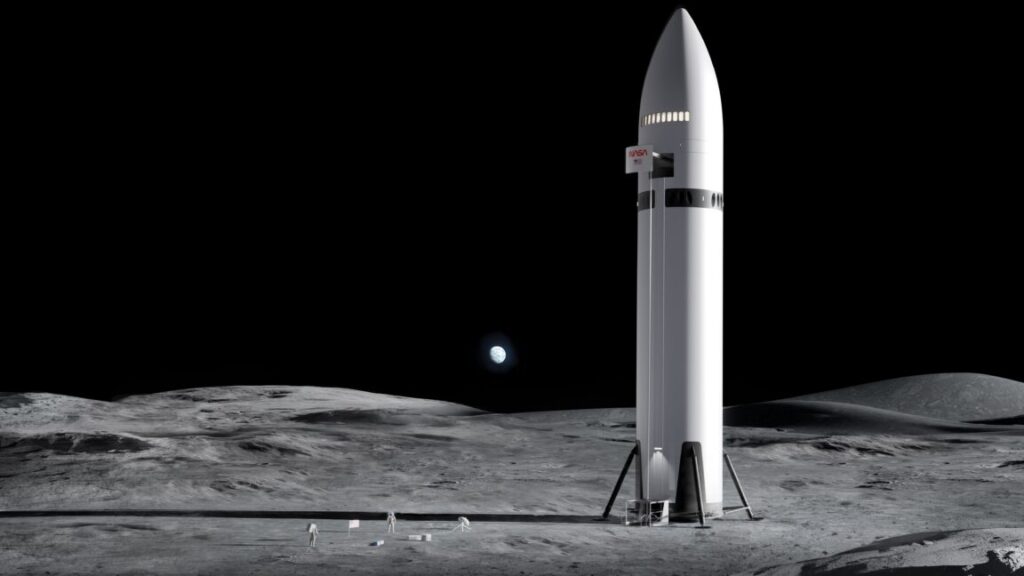

Artist’s illustration of Starship on the surface of the Moon. Credit: SpaceX

Last week, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman unveiled a major shakeup in the Artemis Program, intended to put the nation on a better path back to the Moon. The changes focused largely on increasing the launch cadence of NASA’s large SLS rocket and putting a greater emphasis on lunar surface activities. Days later, the US Senate indicated that it broadly supported these plans.

This is all well and good, but it neglects a critical element of the Artemis program: a lander capable of taking astronauts down to the lunar surface from an orbit around the Moon and back up to rendezvous with Orion. NASA has contracted with SpaceX and Blue Origin to develop these landers, Starship and Blue Moon MK2, respectively.

As part of his announcement, Isaacman said a revamped Artemis III mission will now be used to test one or both of these landers near Earth before they are called upon to land humans on the Moon later this decade.

NASA will launch Artemis III next year, he said, to be followed by one or possibly even two lunar landings in 2028. A single landing before the end of 2028 seems like a stretch, even for glass-half-full optimists in the space community. And for there to be a chance of happening, SpaceX or Blue Origin, or both, need to get hustling quickly.

Can they?

“Challenge every requirement”

Isaacman is mindful of these challenges, and one of his first moves as administrator was meeting with engineers from SpaceX and Blue Origin to hear their ideas for accelerating NASA’s Artemis timeline.

After this meeting on January 13, Isaacman said NASA would do what it could to facilitate the faster development of a Human Landing System: “We will challenge every requirement, clear every obstacle, delete every blocker and empower the team to deliver… and we will do it with time to spare.”

What does this actually mean? It suggests that Isaacman has directed his teams to make working with NASA less cumbersome for SpaceX and Blue Origin.

For example, to reach the Moon during the initial Artemis missions, a lander must dock with the Orion spacecraft. That may sound routine, as spacecraft have been rendezvousing and docking in space for six decades.

However, Orion is saddled with thousands of requirements, and virtually every decision point regarding docking must be signed off on by the lander company—SpaceX or Blue Origin—as well as NASA, Orion’s contractor Lockheed Martin, and the European service module contractor Airbus. Additionally, Orion has a lot of sensitive elements to work around, such as the plumes of its thrusters, and engineers have spent a lot of time working on issues such as ensuring consistent cabin pressures between vehicles. In short, it gets complicated fast.

A carbonated orbit emerges

One way NASA is helping the lander companies is by no longer requiring them to dock with Orion in a near-rectilinear halo orbit, an elliptical orbit that comes as close as 3,000 km to the surface of the Moon and as far as 70,000 km. This is where NASA planned to construct the Lunar Gateway space station, which is now likely to be canceled. It’s a boon for lunar landers since it required more energy to first stop there before dropping down to the surface.

Why not simply have Orion meet the landers in a low-lunar orbit, similar to the Apollo Program? This would allow the landers to consume less propellant on the way down and back up from the Moon. The reason is that, due to a number of poor decisions over the last 15 years, the Orion spacecraft’s service module does not have the performance needed to reach low-lunar orbit and then return safely to Earth. Hence the use of a near-rectilinear halo orbit.

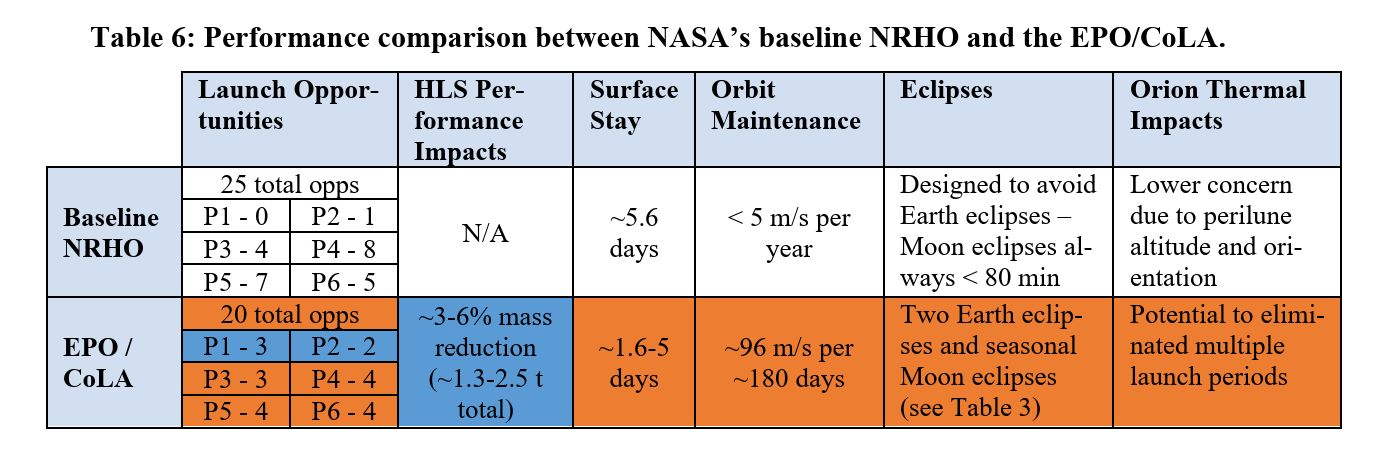

A comparison between the NRHO and EPO/CoLA orbits. Credit: American Astronautical Society conference paper

However, a research paper published in July 2022 by NASA engineers at Johnson Space Center analyzes several other circular and elliptical orbits that Orion could reach with its present propulsive capabilities. Out of this analysis came another useful orbit with a name that just rolls off the tongue: Elliptical Polar Orbit with Coplanar Line of Apsides, or EPO/CoLA.

There are many details about the EPO/CoLA orbit in the research paper, but critically, its closest point to the Moon lies just 100 km above the Moon’s surface (the apolune distance is 6,500 km). For many landing sites, the paper notes, a Human Landing System vehicle can perform a single burn to reach a much lower orbit.

As part of his change in plans, Isaacman said the Space Launch System rocket’s upper stage would be “standardized” for Artemis IV and beyond. That means the first lunar landing mission will use a new upper stage, likely the Centaur V built by United Launch Alliance. This will have more propulsive capabilities than the current rocket, so it is possible that for Artemis IV, Orion could reach an even more favorable orbit (i.e., closer to the Moon, requiring less energy to reach the surface) than EPO/CoLA.

Can Starship be accelerated?

At the end of the day, it’s helpful to find new orbits and relax requirements where appropriate. But it will still be up to the lander contractors to deliver the goods, and for NASA, the sooner the better.

Last November, Ars looked at several ways Starship might be brought online faster as a lunar lander. Perhaps the biggest problem with using Starship as a lander is the need to fly multiple uncrewed tanker missions to refuel Starship in low-Earth orbit before it transits to the Moon and awaits a crew aboard Orion. This necessitates an estimated one- or two-dozen launches.

The best solution we could come up with was flying an optimized, expendable Starship tanker stage that would maximize propellant delivery per flight. When asked about this, though, SpaceX founder Elon Musk shot down the idea. Once Starship begins flying at rate, Musk believes, a dozen or more tanker missions per lunar flight will not pose a major impediment.

So it should come as no surprise that SpaceX has not proposed significant changes to its Human Landing System hardware. In response to NASA’s desire to accelerate the Artemis timeline, the company has indicated that it will prioritize the Human Landing System more as part of the Starship program. The company also suggested that eliminating the requirement to dock in near-rectilinear halo orbit could open up new mission plans, including potentially docking with Orion in orbit around Earth rather than the Moon.

What about Blue Origin?

Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos, has been more responsive. Last October, Ars reported that the company had started working on a faster architecture that would not require orbital refueling. A month later, Blue Origin’s chief executive, Dave Limp, said the company “would move heaven and Earth” to help NASA reach the Moon sooner.

Based on recent documents reviewed by Ars, the company is continuing to refine its plan for a human lunar landing. Without a requirement to rendezvous in a near-rectilinear halo orbit, a lunar landing could potentially be accomplished with as few as three launches of Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket. This would require the more powerful 9×4 variant of the New Glenn rocket now in development. The EPO/CoLA orbit described above enables such a mission profile.

One mission plan seen by Ars shows the launch of a simplified MK2 lander on one rocket, and two more launches of transfer stages, which subsequently dock in low-Earth orbit. The first transfer stage pushes this stack out of low-Earth orbit before separating. The second transfer stage pushes the lander into EPO/CoLA, where it docks with Orion and two astronauts move on board MK2. This second transfer stage then moves the lander to a 15 x 100 km lunar orbit before separating. MK2 then flies down to the Moon.

After a short stay on the Moon, the interim MK2 lander would ascend back to the EPO/CoLA, where it meets up with Orion.

There are plenty of questions about the readiness of the Blue Origin hardware, of course. And there are a lot of moving pieces now with the Moon landing moving to Artemis IV and the probable use of new orbits for a rendezvous with Orion near the Moon. So all of this remains very notional.

Neither NASA nor Blue Origin has spoken publicly about their accelerated landing plans. Hopefully, that will change soon, because it’s entirely possible that NASA’s best chance to reach the Moon before China will come down to the ability of a company that proudly sports a turtle as a mascot to move a little more quickly.

Note: This story was updated at 11: 30 am ET Friday with additional information.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

With Gateway likely gone, where will lunar landers rendezvous with Orion? Read More »