In a not-so-subtle signal to regulators, Blue Origin says New Glenn is ready

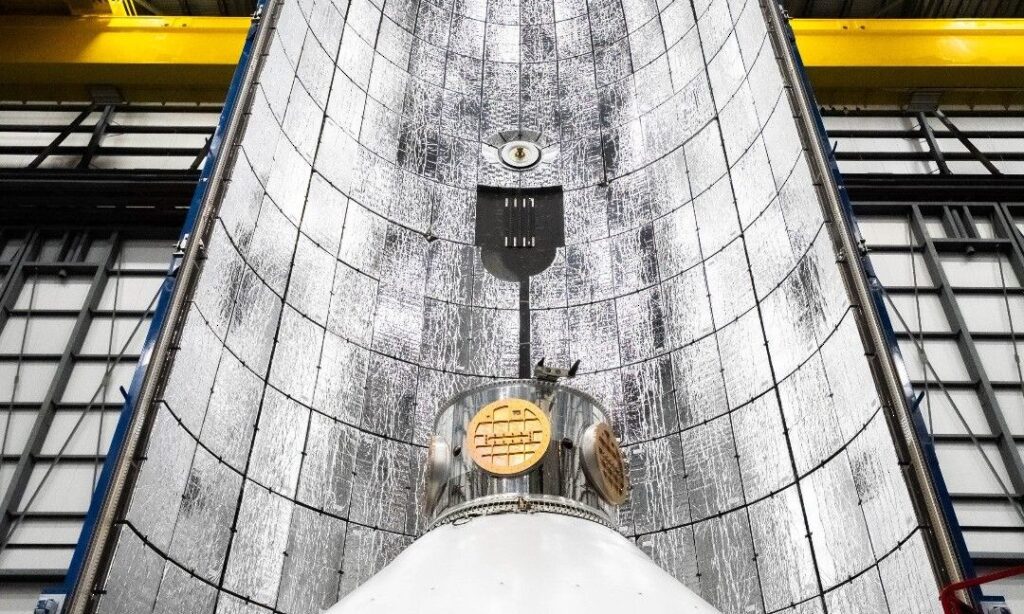

Blue Origin said Tuesday that the test payload for the first launch of its new rocket, New Glenn, is ready for liftoff. The company published an image of the “Blue Ring” pathfinder nestled up against one half of the rocket’s payload fairing.

“There is a growing demand to quickly move and position equipment and infrastructure in multiple orbits,” the company’s chief executive, Dave Limp, said on LinkedIn. “Blue Ring has advanced propulsion and communication capabilities for government and commercial customers to handle these maneuvers precisely and efficiently.”

This week’s announcement—historically Blue Origin has been tight-lipped about new products, but is opening up more as it nears the debut of its flagship New Glenn rocket—appears to serve a couple of purposes.

All Blue wants for Christmas is…

First of all, the relatively small payload contrasted with the size of the payload fairing highlights the greater volume the rocket offers over most conventional boosters. New Glenn’s payload fairing is 7 meters (23 feet) in diameter as opposed to the more conventional 5 meters (16.4 feet). It looks roomy inside.

Additionally, the company appears to be publicly signaling the Federal Aviation Administration and other regulatory agencies that it believes New Glenn is ready to fly, pending approval to conduct a hot fire test at Launch Complex-36, and then for a liftoff from Florida. This is a not-so-subtle message to regulators to please hurry up and complete the paperwork necessary for launch activities. It is not clear what is holding up the hot-fire and launch approval in this case, but it is often environmental issues or certification of a flight termination system.

Blue Origin’s release on Tuesday was carefully worded. The headline said New Glenn was “on track” for a launch this year and stated that the Blue Ring payload is “ready” for a launch this year. As yet there is no notional or public launch date. The hot-fire test has been delayed multiple times since the company put the rocket on its launch pad on Nov. 23. It had been targeting November for the test, and more recently, this past weekend.

After years of delays for the rocket, originally due to debut in 2020, Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos hired a new chief executive to run the company a little more than a year ago. Limp, an executive from Amazon, was given the mandate to change Blue Origin’s slower-moving culture to be more nimble and urgent and was told to launch New Glenn by the end of 2024.

In a not-so-subtle signal to regulators, Blue Origin says New Glenn is ready Read More »