Rocket Report: Stoke is stoked; sovereignty is the buzzword in Europe

“The idea that we will be able to do it through America… I think is very, very doubtful.”

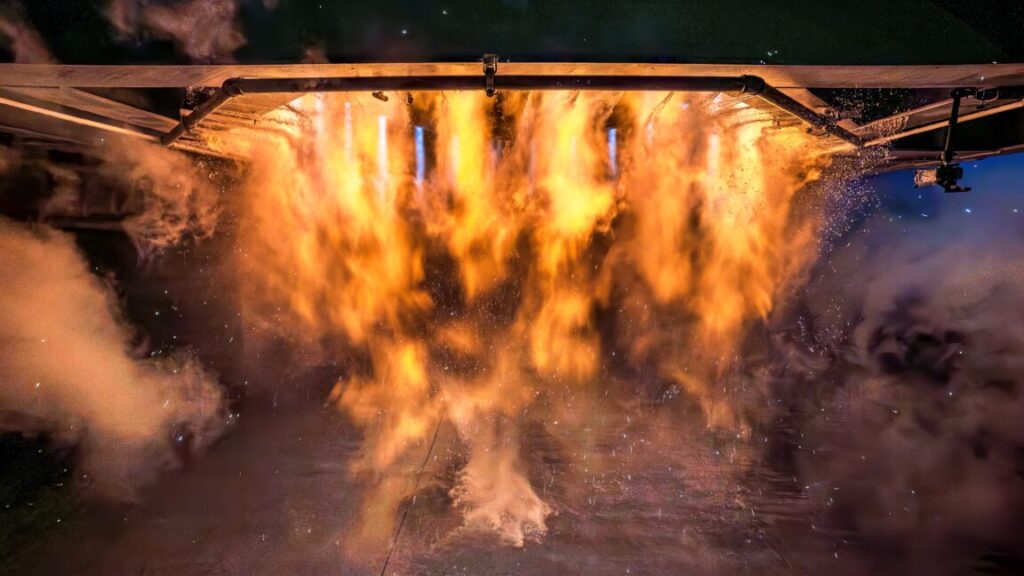

Stoke Space’s Andromeda upper stage engine is hot-fired on a test stand. Credit: Stoke Space

Welcome to Edition 7.37 of the Rocket Report! It’s been interesting to watch how quickly European officials have embraced ensuring they have a space launch capability independent of other countries. A few years ago, European government satellites regularly launched on Russian Soyuz rockets, and more recently on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets from the United States. Russia is now non grata in European government circles, and the Trump administration is widening the trans-Atlantic rift. European leaders have cited the Trump administration and its close association with Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, as prime reasons to support sovereign access to space, a capability currently offered only by Arianespace. If European nations can reform how they treat their commercial space companies, there’s enough ambition, know-how, and money in Europe to foster a competitive launch industry.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

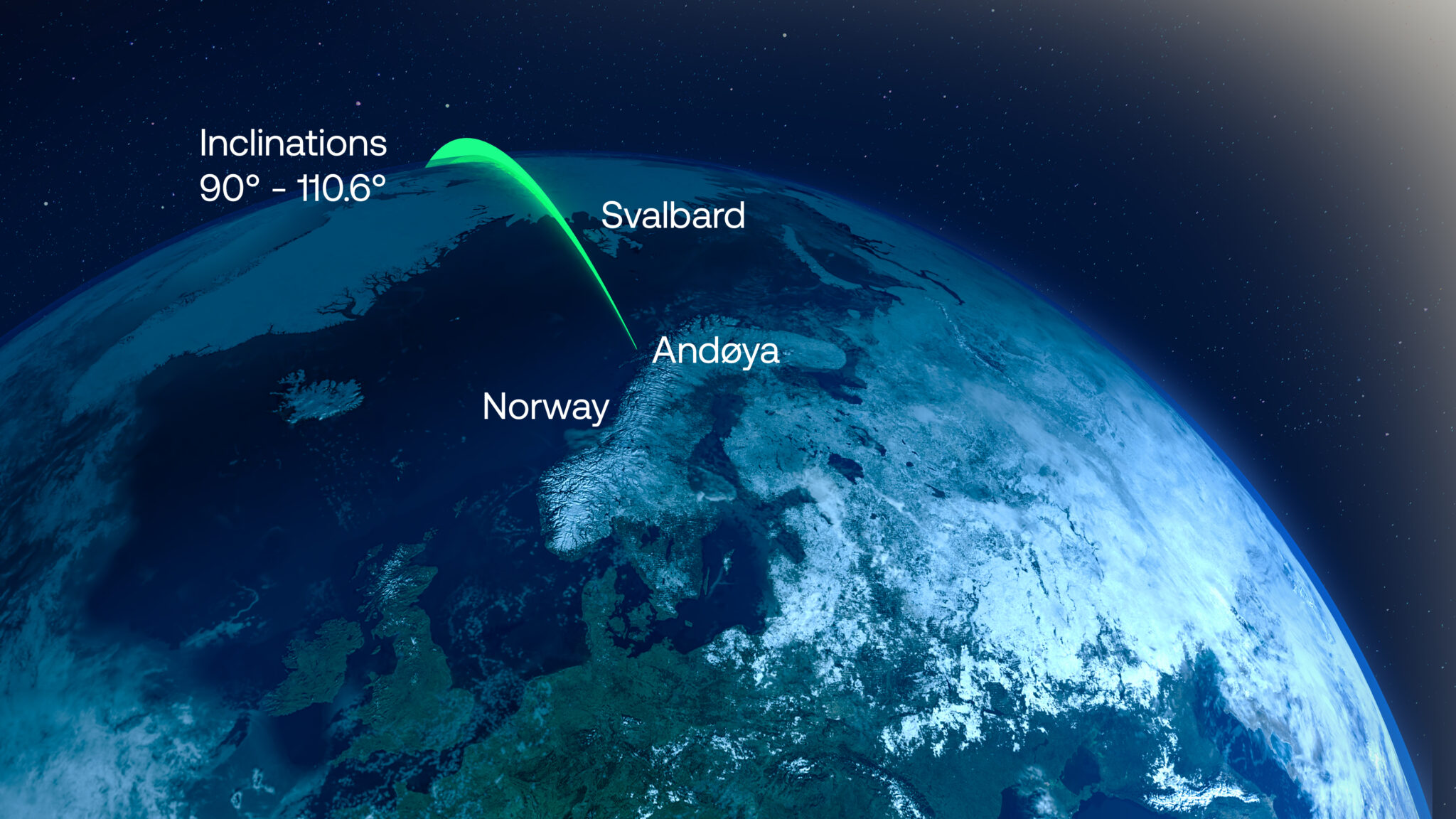

Isar Aerospace aims for weekend launch. A German startup named Isar Aerospace will try to launch its first rocket Saturday, aiming to become the first in a wave of new European launch companies to reach orbit, Ars reports. The Spectrum rocket consists of two stages, stands about 92 feet (28 meters) tall, and can haul payloads up to 1 metric ton (2,200 pounds) into low-Earth orbit. Based in Munich, Isar was founded by three university graduate students in 2018. Isar scrubbed a launch attempt Monday due to unfavorable winds at the launch site in Norway.

From the Arctic … Notably, this will be the first orbital launch attempt from a launch pad in Western Europe. The French-run Guiana Space Center in South America is the primary spaceport for European rockets. Virgin Orbit staged an airborne launch attempt from an airport in the United Kingdom in 2023, and the Plesetsk Cosmodrome is located in European Russia. The launch site for Isar is named Andøya Spaceport, located about 650 miles (1,050 kilometers) north of Oslo, inside the Arctic Circle. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

A chance for competition in Europe. The European Space Agency is inviting proposals to inject competition into the European launch market, an important step toward fostering a dynamic multiplayer industry officials hope one day will mimic that of the United States, Ars reports. The near-term plan for the European Launcher Challenge is for ESA to select companies for service contracts to transport ESA and other European government payloads to orbit from 2026 through 2030. A second component of the challenge is for companies to perform at least one demonstration of an upgraded launch vehicle by 2028. The competition is open to any European company working in the launch business.

Challenging the status quo … This is a major change from how ESA has historically procured launch services. Arianespace has been the only European launch provider available to ESA and other European institutions for more than 40 years. But there are private companies across Europe at various stages of developing their own small launchers, and potentially larger rockets, in the years ahead. With the European Launcher Challenge, ESA will provide each of the winners up to 169 million euros ($182 million), a significant cash infusion that officials hope will shepherd Europe’s nascent private launch industry toward liftoff. Companies like Isar Aerospace, Rocket Factory Augsburg, MaiaSpace, and PLD Space are among the contenders for ESA contracts.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Rocket Lab launches eight satellites. Rocket Lab launched eight satellites Wednesday for a German company that is expanding its constellation to detect and track wildfires, Space News reports. An Electron rocket lifted off from New Zealand and completed deploying its payload of eight CubeSats for OroraTech about 55 minutes later, placing them into Sun-synchronous orbits at an altitude of about 341 miles (550 kilometers). This was Rocket Lab’s fifth launch of the year, and the third in less than two weeks.

Fire goggles … OroraTech launched three satellites before this mission, fusing data from those satellites and government missions to detect and track wildfires. The new satellites are designed to fill a gap in coverage in the afternoon, a peak time for wildfire formation and spread. OroraTech plans to launch eight more satellites later this year. Wildfire monitoring from space is becoming a new application for satellite technology. Last month, OroraTech partnered with Spire for a contract to build a CubeSat constellation called WildFireSat for the Canadian Space Agency. Google is backing FireSat, another constellation of more than 50 satellites to be deployed in the coming years to detect and track wildfires. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Should Britain have a sovereign launch capability? A UK House of Lords special inquiry committee has heard from industry experts on the importance of fostering a sovereign launch capability, European Spaceflight reports. On Monday, witnesses from the UK space industry testified that the nation shouldn’t rely on others, particularly the United States, to put satellites into orbit. “The idea that we will be able to do it through America… certainly in today’s, you know, the last 50 days, I think is very, very doubtful. The UK needs access to space,” said Scott Hammond, deputy CEO of SaxaVord Spaceport in Scotland.

Looking inward … A representative from one of the most promising UK launch startups agreed. “Most people who are looking to launch are beholden to the United States solutions or services that are there,” said Alan Thompson, head of government affairs at Skyrora. “Without having our own home-based or UK-based service provider, we risk not having that voice and not being able to undertake all these experiments or be able to manifest ourselves better in space.” The UK is the only nation to abandon an independent launch capability after putting a satellite into orbit. The British government canceled the Black Arrow rocket in the early 1970s, citing financial reasons. A handful of companies, including Skyrora, is working to restore the orbital launch business to the UK.

This rocket engine CEO faces some salacious allegations. The Independent published what it described as an exclusive report Monday describing a lawsuit filed against the CEO of RocketStar, a New York-based company that says its mission is “improving upon the engines that power us to the stars.” Christopher Craddock is accused of plundering investor funds to underwrite pricey jaunts to Europe, jewelry for his wife, child support payments, and, according to the company’s largest investor, “airline tickets for international call girls to join him for clandestine weekends in Miami,” The Independent reports. Craddock established RocketStar in 2014 after financial regulators barred him from working on Wall Street over a raft of alleged violations.

Go big or go home … The $6 million lawsuit filed by former CEO Michael Mojtahedi alleges RocketStar “is nothing more than a Ponzi scheme… [that] has been predicated on Craddock’s ability to con new people each time the company has run out of money.” On its website, RocketStar says its work focuses on aerospike rocket engines and a “FireStar Fusion Drive, the world’s first electric propulsion device enhanced with nuclear fusion.” These are tantalizing technologies that have proven elusive for other rocket companies. RocketStar’s attorney told The Independent: “The company denies the allegations and looks forward to vindicating itself in court.”

Another record for SpaceX. Last Thursday, SpaceX launched a batch of clandestine SpaceX-built surveillance satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, Spaceflight Now reports. This was the latest in a series of flights populating the NRO’s constellation of low-Earth orbit reconnaissance satellites. What was unique about this mission was its use of a Falcon 9 first stage booster that flew to space just nine days prior with a NASA astronomy satellite. The successful launch broke the record for the shortest span between flights of the same Falcon 9 booster, besting a 13.5-day turnaround in November 2024.

A mind-boggling number of launches … This flight also marked the 450th launch of a Falcon 9 rocket since its debut in 2010, and the 139th within a 365-day period, despite suffering its first mission failure in nearly 10 years and a handful of other glitches. SpaceX’s launch pace is unprecedented in the history of the space industry. No one else is even close. In the last Rocket Report I authored, I wrote that SpaceX’s steamroller no longer seems to be rolling downhill. That may be the case as the growth in the Falcon 9 launch cadence has slowed, but it’s hard for me to see anyone else matching SpaceX’s launch rate until at least the 2030s.

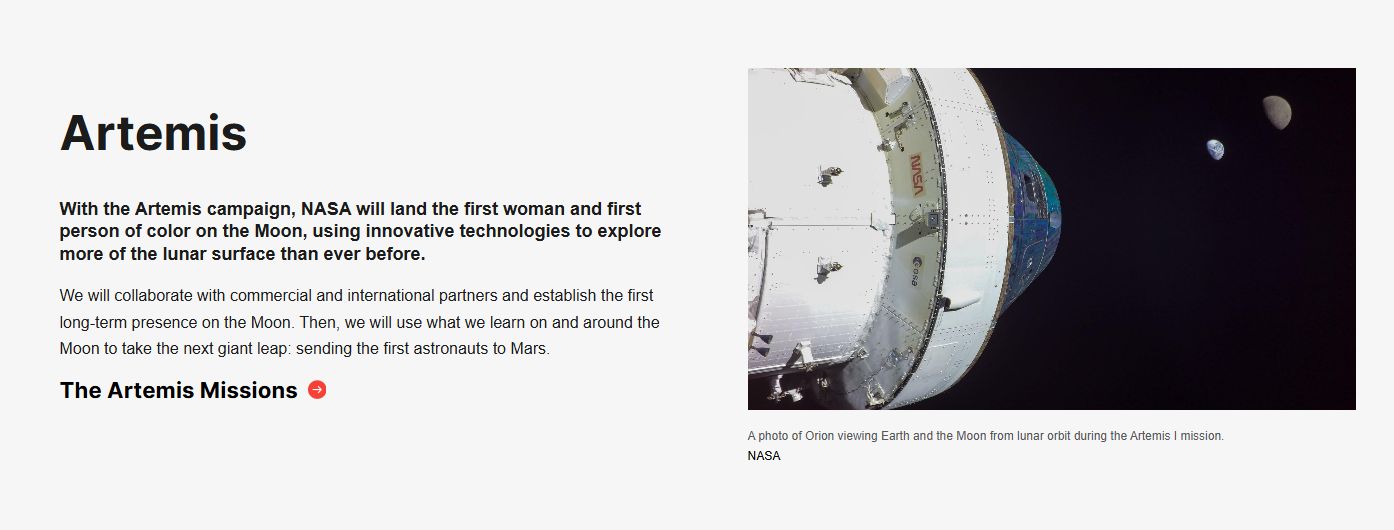

Rocket Lab and Stoke Space find an on-ramp. Space Systems Command announced Thursday that it selected Rocket Lab and Stoke Space to join the Space Force’s National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program. The contracts have a maximum value of $5.6 billion, and the Space Force will dole out “task orders” for individual missions as they near launch. Rocket Lab and Stoke Space join SpaceX, ULA, and Blue Origin as eligible launch providers for lower-priority national security satellites, a segment of missions known as Phase 3 Lane 1 in the parlance of the Space Force. For these missions, the Space Force won’t require certification of the rockets, as the military does for higher-value missions in the so-called “Lane 2” segment. However, Rocket Lab and Stoke Space must complete at least one successful flight of their new Neutron and Nova rockets before they are cleared to launch national security payloads.

Stoked at Stoke … This is a big win for Rocket Lab and Stoke. For Rocket Lab, it bolsters the business case for the medium-class Neutron rocket it is developing for flights from Wallops Island, Virginia. Neutron will be partially reusable with a recoverable first stage. But Rocket Lab already has a proven track record with its smaller Electron launch vehicle. Stoke hasn’t launched anything, and it has lofty ambitions for a fully reusable two-stage rocket called Nova. This is a huge vote of confidence in Stoke. When the Space Force released its invitation for an on-ramp to the NSSL program last year, it said bidders must show a “credible plan for a first launch by December 2025.” Smart money is that neither company will launch its rockets by the end of this year, but I’d love to be proven wrong.

Falcon 9 deploys spy satellite. Monday afternoon, a SpaceX Falcon 9 took flight from Florida’s Space Coast and delivered a national security payload designed, built, and operated by the National Reconnaissance Office into orbit, Florida Today reports. Like almost all NRO missions, details about the payload are classified. The mission codename was NROL-69, and the launch came three-and-a-half days after SpaceX launched another NRO mission from California. While we have some idea of what SpaceX launched from California last week, the payload for the NROL-69 mission is a mystery.

Space sleuthing … There’s an online community of dedicated skywatchers who regularly track satellites as they sail overhead around dawn and dusk. The US government doesn’t publish the exact orbital parameters for its classified spy satellites (they used to), but civilian trackers coordinate with one another, and through a series of observations, they can produce a pretty good estimate of a spacecraft’s orbit. Marco Langbroek, a Dutch archeologist and university lecturer on space situational awareness, is one of the best at this, using publicly available information about the flight path of a launch to estimate when the satellite will fly overhead. He and three other observers in Europe managed to locate the NROL-69 payload just two days after the launch, plotting the object in an orbit between 700 and 1,500 kilometers at an inclination of 64.1 degrees to the equator. Analysts speculated this mission might carry a pair of naval surveillance spacecraft, but this orbit doesn’t match up well with any known constellations of NRO satellites.

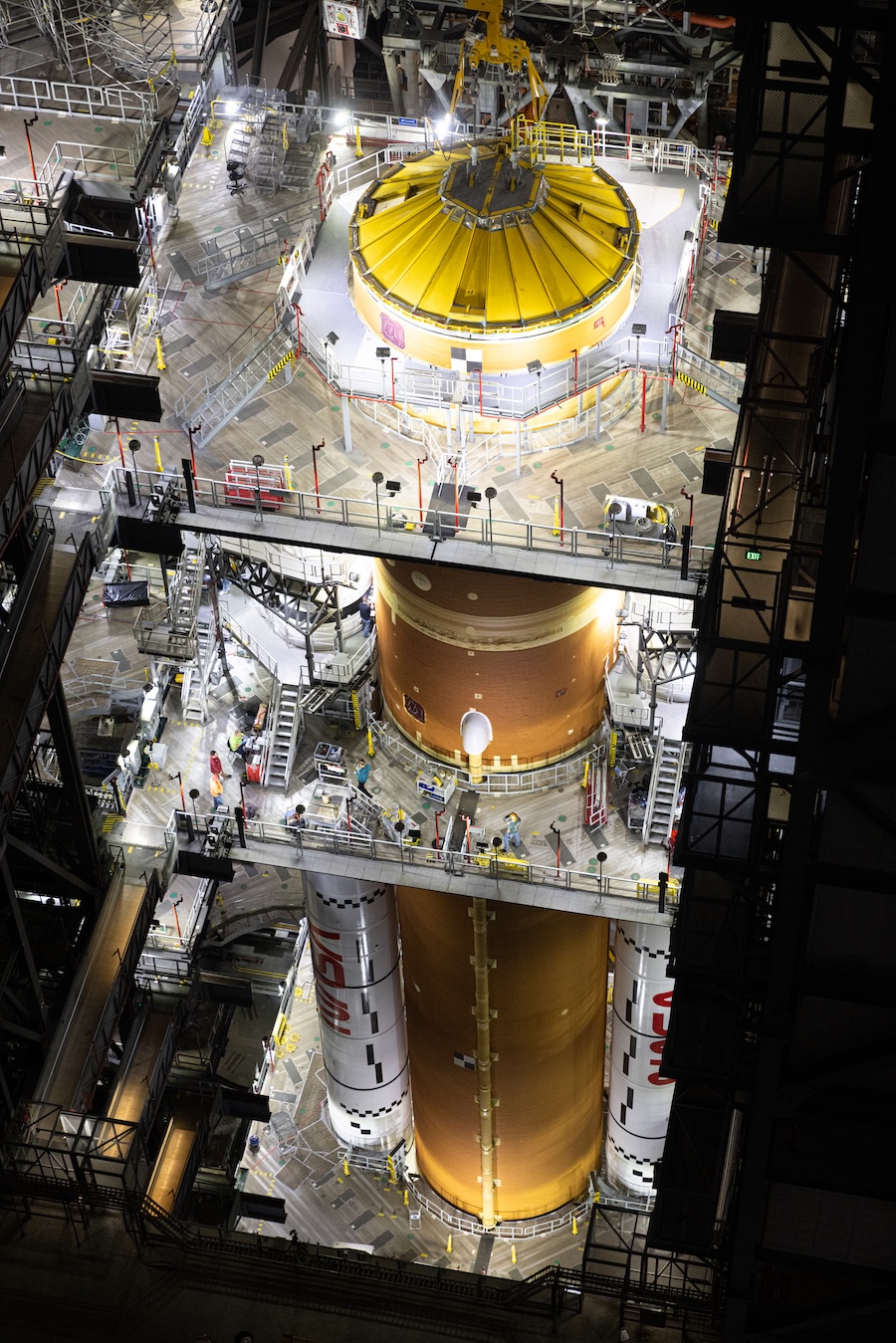

NASA continues with Artemis II preps. Late Saturday night, technicians at Kennedy Space Center in Florida moved the core stage for NASA’s second Space Launch System rocket into position between the vehicle’s two solid-fueled boosters, Ars reports. Working inside the iconic 52-story-tall Vehicle Assembly Building, ground teams used heavy-duty cranes to first lift the butterscotch orange core stage from its cradle, then rotate it to a vertical orientation and lift it into a high bay, where it was lowered into position on a mobile launch platform. The 212-foot-tall (65-meter) core stage is the largest single hardware element for the Artemis II mission, which will send a team of four astronauts around the far side of the Moon and back to Earth as soon as next year.

Looking like a go … With this milestone, the slow march toward launch continues. A few months ago, some well-informed people in the space community thought there was a real possibility the Trump administration could quickly cancel NASA’s Space Launch System, the high-priced heavy-lifter designed to send astronauts from the Earth to the Moon. The most immediate possibility involved terminating the SLS program before it flies with Artemis II. This possibility appears to have been overcome by circumstances. The rockets most often mentioned as stand-ins for the Space Launch System—SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn—aren’t likely to be cleared for crew missions for at least several years. The long-term future of the Space Launch System remains in doubt.

Space Force says Vulcan is good to go. The US Space Force on Wednesday announced that it has certified United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket to conduct national security missions, Ars reports. “Assured access to space is a core function of the Space Force and a critical element of national security,” said Brig. Gen. Kristin Panzenhagen, program executive officer for Assured Access to Space, in a news release. “Vulcan certification adds launch capacity, resiliency, and flexibility needed by our nation’s most critical space-based systems.” The formal announcement closes a yearslong process that has seen multiple delays in the development of the Vulcan rocket, as well as two anomalies in recent years that were a further setback to certification.

Multiple options … This certification allows ULA’s Vulcan to launch the military’s most sensitive national security missions, a separate lot from those Rocket Lab and Stoke Space are now eligible for (as we report in a separate Rocket Report entry). It elevates Vulcan to launch these missions alongside SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. Vulcan will not be the next rocket that the company launches, however. First up is one of the company’s remaining Atlas V boosters, carrying Project Kuiper broadband satellites for Amazon. This launch could occur in April, although ULA has not set a date. This will be followed by the first Vulcan national security launch, which the Space Force says could occur during the coming “summer.”

Next three launches

March 29: Spectrum | “Going Full Spectrum” | Andøya Spaceport, Norway | 11: 30 UTC

March 29: Long March 7A | Unknown Payload | Wenchang Space Launch Site, China | 16: 05 UTC

March 30: Alpha | LM-400 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California | 13: 37 UTC

Rocket Report: Stoke is stoked; sovereignty is the buzzword in Europe Read More »