Lunar Gateway’s skeleton is complete—its next stop may be Trump’s chopping block

Officials blame changing requirements for much of the delays and rising costs. NASA managers dramatically changed their plans for the Gateway program in 2020, when they decided to launch the PPE and HALO on the same rocket, prompting major changes to their designs.

Jared Isaacman, Trump’s nominee for NASA administrator, declined to commit to the Gateway program during a confirmation hearing before the Senate Commerce Committee on April 9. Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), the committee’s chairman, pressed Isaacman on the Lunar Gateway. Cruz is one of the Gateway program’s biggest backers in Congress since it is managed by Johnson Space Center in Texas. If it goes ahead, Gateway would guarantee numerous jobs at NASA’s mission control in Houston throughout its 15-year lifetime.

“That’s an area that if I’m confirmed, I would love to roll up my sleeves and further understand what’s working right?” Isaacman replied to Cruz. “What are the opportunities the Gateway presents to us? And where are some of the challenges, because I think the Gateway is a component of many programs that are over budget and behind schedule.”

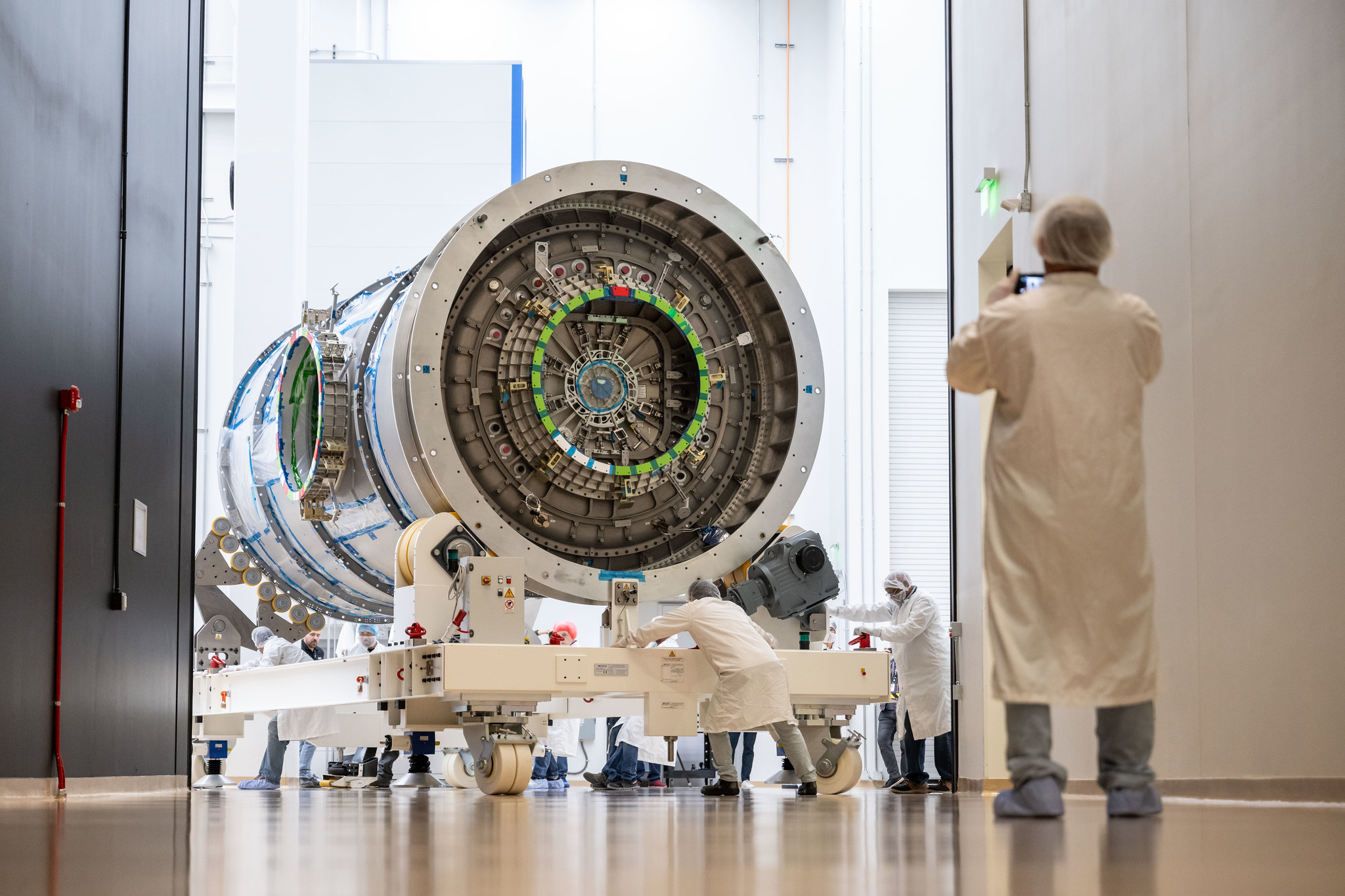

The pressure shell for the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) module arrived in Gilbert, Arizona, last week for internal outfitting. Credit: NASA/Josh Valcarcel

Checking in with Gateway

Nevertheless, the Gateway program achieved a milestone one week before Isaacman’s confirmation hearing. The metallic pressure shell for the HALO module was shipped from its factory in Italy to Arizona. The HALO module is only partially complete, and it lacks life support systems and other hardware it needs to operate in space.

Over the next couple of years, Northrop Grumman will outfit the habitat with those components and connect it with the Power and Propulsion Element under construction at Maxar Technologies in Silicon Valley. This stage of spacecraft assembly, along with prelaunch testing, often uncovers problems that can drive up costs and trigger more delays.

Ars recently spoke with Jon Olansen, a bio-mechanical engineer and veteran space shuttle flight controller who now manages the Gateway program at Johnson Space Center. A transcript of our conversation with Olansen is below. It is lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Ars: The HALO module has arrived in Arizona from Italy. What’s next?

Olansen: This HALO module went through significant effort from the primary and secondary structure perspective out at Thales Alenia Space in Italy. That was most of their focus in getting the vehicle ready to ship to Arizona. Now that it’s in Arizona, Northrop is setting it up in their facility there in Gilbert to be able to do all of the outfitting of the systems we need to actually execute the missions we want to do, keep the crew safe, and enable the science that we’re looking to do. So, if you consider your standard spacecraft, you’re going to have all of your command-and-control capabilities, your avionics systems, your computers, your network management, all of the things you need to control the vehicle. You’re going to have your power distribution capabilities. HALO attaches to the Power and Propulsion Element, and it provides the primary power distribution capability for the entire station. So that’ll all be part of HALO. You’ll have your standard thermal systems for active cooling. You’ll have the vehicle environmental control systems that will need to be installed, [along with] some of the other crew systems that you can think of, from lighting, restraint, mobility aids, all the different types of crew systems. Then, of course, all of our science aspects. So we have payload lockers, both internally, as well as payload sites external that we’ll have available, so pretty much all the different systems that you would need for a human-rated spacecraft.

Ars: What’s the latest status of the Power and Propulsion Element?

Olansen: PPE is fairly well along in their assembly and integration activities. The central cylinder has been integrated with the propulsion tanks… Their propulsion module is in good shape. They’re working on the avionics shelves associated with that spacecraft. So, with both vehicles, we’re really trying to get the assembly done in the next year or so, so we can get into integrated spacecraft testing at that point in time.

Ars: What’s in the critical path in getting to the launch pad?

Olansen: The assembly and integration activity is really the key for us. It’s to get to the full vehicle level test. All the different activities that we’re working on across the vehicles are making substantive progress. So, it’s a matter of bringing them all in and doing the assembly and integration in the appropriate sequences, so that we get the vehicles put together the way we need them and get to the point where we can actually power up the vehicles and do all the testing we need to do. Obviously, software is a key part of that development activity, once we power on the vehicles, making sure we can do all the control work that we need to do for those vehicles.

[There are] a couple of key pieces I will mention along those lines. On the PPE side, we have the electrical propulsion system. The thrusters associated with that system are being delivered. Those will go through acceptance testing at the Glenn Research Center [in Ohio] and then be integrated on the spacecraft out at Maxar; so that work is ongoing as we speak. Out at ESA, ESA is providing the HALO lunar communication system. That’ll be delivered later this year. That’ll be installed on HALO as part of its integrated test and checkout and then launch on HALO. That provides the full communication capability down to the lunar surface for us, where PPE provides the communication capability back to Earth. So, those are key components that we’re looking to get delivered later this year.

Jon Olansen, manager of NASA’s Gateway program at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Credit: NASA/Andrew Carlsen

Ars: What’s the status of the electric propulsion thrusters for the PPE?

Olansen: The first one has actually been delivered already, so we’ll have the opportunity to go through, like I said, the acceptance testing for those. The other flight units are right on the heels of the first one that was delivered. They’ll make it through their acceptance testing, then get delivered to Maxar, like I said, for integration into PPE. So, that work is already in progress. [The Power and Propulsion Element will have three xenon-fueled 12-kilowatt Hall thrusters produced by Aerojet Rocketdyne, and four smaller 6-kilowatt thrusters.]

Ars: The Government Accountability Office (GAO) outlined concerns last year about keeping the mass of Gateway within the capability of its rocket. Has there been any progress on that issue? Will you need to remove components from the HALO module and launch them on a future mission? Will you narrow your launch windows to only launch on the most fuel-efficient trajectories?

Olansen: We’re working the plan. Now that we’re launching the two vehicles together, we’re working mass management. Mass management is always an issue with spacecraft development, so it’s no different for us. All of the things you described are all knobs that are in the trade space as we proceed, but fundamentally, we’re working to design the optimal spacecraft that we can, first. So, that’s the key part. As we get all the components delivered, we can measure mass across all of those components, understand what our integrated mass looks like, and we have several different options to make sure that we’re able to execute the mission we need to execute. All of those will be balanced over time based on the impacts that are there. There’s not a need for a lot of those decisions to happen today. Those that are needed from a design perspective, we’ve already made. Those that are needed from enabling future decisions, we’ve already made all of those. So, really, what we’re working through is being able to, at the appropriate time, make decisions necessary to fly the vehicle the way we need to, to get out to NRHO [Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit, an elliptical orbit around the Moon], and then be able to execute the Artemis missions in the future.

Ars: The GAO also discussed a problem with Gateway’s controllability with something as massive as Starship docked to it. What’s the latest status of that problem?

Olansen: There are a number of different risks that we work through as a program, as you’d expect. We continue to look at all possibilities and work through them with due diligence. That’s our job, to be able to do that on a daily basis. With the stack controllability [issue], where that came from for GAO, we were early in the assessments of what the potential impacts could be from visiting vehicles, not just any one [vehicle] but any visiting vehicle. We’re a smaller space station than ISS, so making sure we understand the implications of thruster firings as vehicles approach the station, and the implications associated with those, is where that stack controllability conversation came from.

The bus that Maxar typically designs doesn’t have to generally deal with docking. Part of what we’ve been doing is working through ways that we can use the capabilities that are already built into that spacecraft differently to provide us the control authority we need when we have visiting vehicles, as well as working with the visiting vehicles and their design to make sure that they’re minimizing the impact on the station. So, the combination of those two has largely, over the past year since that report came out, improved where we are from a stack controllability perspective. We still have forward work to close out all of the different potential cases that are there. We’ll continue to work through those. That’s standard forward work, but we’ve been able to make some updates, some software updates, some management updates, and logic updates that really allow us to control the stack effectively and have the right amount of control authority for the dockings and undockings that we will need to execute for the missions.

Lunar Gateway’s skeleton is complete—its next stop may be Trump’s chopping block Read More »