Rocket Report: Two big Asian reuse milestones, Vandenberg becomes SpaceX west

“This is potentially going to be a problem.”

Landspace shows off its Zhuque-3 rocket on the launch pad. Credit: Landspace

Welcome to Edition 7.49 of the Rocket Report! You may have noticed we are a little late with the report this week, and that is due to the Juneteenth holiday celebrated in the United States on Thursday. But that hasn’t stopped a torrent of big news this week, from exploding Starships to significant reuse milestones being reached in Asia.

As always, we welcome reader submissions, and if you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Honda stamps passport to the skies with a hopper. An experimental reusable rocket developed by the research and development arm of Honda Motor Company flew to an altitude of nearly 900 feet (275 meters) Tuesday, then landed with pinpoint precision at the carmaker’s test facility in northern Japan, Ars reports. Honda’s hopper is the first prototype rocket outside of the United States and China to complete a flight of this kind, demonstrating vertical takeoff and vertical landing technology that could underpin the development of a reusable launch vehicle.

A legitimately impressive feat… Honda has been quiet on this rocket project since a brief media blitz nearly four years ago. Developed in-house by Honda R&D Company, the rocket climbed vertically from a pedestal at the company’s test site in southeastern Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s main islands, before landing less than a meter from its target. Honda said its launch vehicle is “still in the fundamental research phase,” and the company has made no decision whether to commercialize the rocket program. (submitted by Fernwaerme, TFargo04, Biokleen, Rendgrish, and astromog)

European launch companies seek protection. In a joint statement published on Monday, Arianespace and Avio called for European missions to be launched aboard European rockets, European Spaceflight reports. The statement warned that without “sustained support,” European rocket builders risked losing out to institutionally backed competitors from the US.

Seeking to permanently embed European preference… “Major space powers support their industries through stable and guaranteed institutional markets, enabling long-term investments, innovation, and the preservation of leadership,” explained the statement. The pair argues that Europe risks falling behind not due to a lack of technical capability but because of structural market weaknesses. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

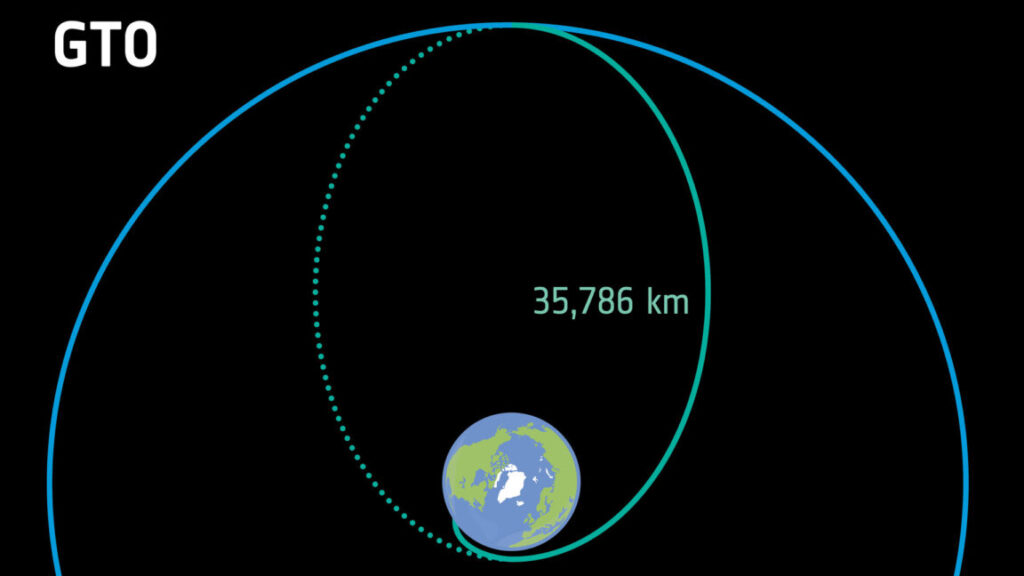

Increasing launch cadence may threaten ozone layer. The rapidly growing number of rocket launches could slow the recovery of the ozone layer, a new study in the journal Nature finds. The ozone layer is healing due to countries phasing out CFCs, but rocket launches could slow its recovery if the space industry continues growing, Radio New Zealand reports. “At the moment, it’s not a problem because the launches happen too infrequently,” said University of Canterbury atmospheric scientist Laura Revell, one of the authors of the study. “As we get more and more launches taking place—because there are companies out there with very bold ambitions to increase launch frequency—this is potentially going to be a problem.”

Forecasting a lot of growth in launch… In a conservative growth scenario, about 900 total launches a year, there is some ozone loss but not significant amounts,” said Revell. “But when we look at a more ambitious scenario, when we looked at the upper limits of what might be launched in future—around 2,000 launches year—we saw levels of ozone loss that are concerning in the context of ozone recovery,” she said. Ozone losses are driven by the chlorine produced from solid rocket motor propellant and black carbon, which is emitted from most propellants, the study says. (submitted by Zaphod Harkonnen)

Space may soon be pay-to-play with the FAA. The Federal Aviation Administration may soon levy fees on companies seeking launch and reentry licenses, a new tack in the push to give the agency the resources it needs to keep up with the rapidly growing commercial space industry, Ars reports. The text of a budget reconciliation bill released by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) earlier this month calls for the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, known as AST, to begin charging licensing fees to space companies next year.

The price of poker keeps going up… The fees would phase in over eight years, after which the FAA would adjust them to keep pace with inflation. The money would go into a trust fund to help pay for the operating costs of the FAA’s commercial space office. Cruz’s section of the Senate reconciliation bill calls for the FAA to charge commercial space companies per pound of payload mass, beginning with 25 cents per pound in 2026 and increasing to $1.50 per pound in 2033. Subsequent fee rates would change based on inflation. The overall fee per launch or entry would be capped at $30,000 in 2026, increasing to $200,000 in 2033, and then be adjusted to keep pace with inflation.

Landspace tests Zhuque-3 rocket. Chinese launch startup Landspace carried out a breakthrough static fire test Friday as it builds towards an orbital launch attempt with its Zhuque-3 rocket, Space News reports. The Zhuque-3’s nine methane-liquid oxygen engines ignited in sequence and fired for 45 seconds, including gimbal control testing, before shutting down as planned. The successful test lays a solid foundation for the upcoming inaugural flight of the Zhuque-3 and for the country’s reusable launch vehicle technology, Landspace said.

Similar in design to Falcon 9 … Friday’s static fire test used a first-stage identical to the one intended for Zhuque-3’s inaugural flight, planned for later this year, and covered the full ground-based launch preparation and ignition sequence, including propellant loading, tank pressurization, staged engine ignition, steady-state operation and a programmed shutdown. Payload capacity to low Earth orbit will be 21 metric tons when expendable, or up to 18,300 kg when the first stage is recovered downrange. Alternatively, it can carry 12,500 kg to LEO when returning to the launch site.

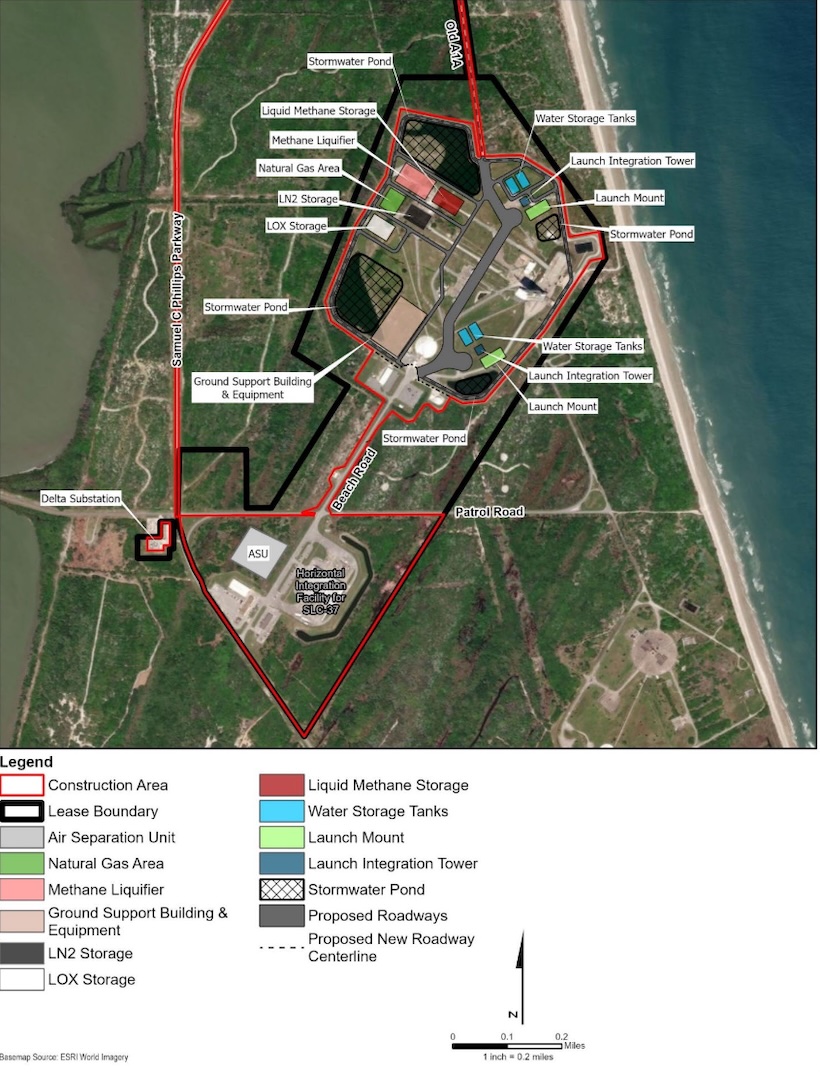

Kuiper launch scrubs due to hardware issue. United Launch Alliance and its customer, Amazon, will have to wait longer for the second launch of Amazon’s Project Kuiper satellites following a scrub on Monday afternoon. “United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 551 carrying Amazon’s second Project Kuiper mission, Kuiper 2, is delayed due to an engineering observation of an elevated purge temperature within the booster engine,” ULA said in a statement. “The team will evaluate the hardware, and we will release a new launch date when available.”

Back to the VIF in a spiff… On Tuesday, ULA rolled the Atlas V rocket back to its Vertical Integration Facility to address the issue with the nitrogen purge line on the vehicle. In addition to this mission, ULA has six more Atlas 5 rockets that have been purchased by Amazon to fly satellites for its constellation. As of Friday morning, ULA had not set a new launch date for the Kuiper 2 mission, but it could take place early next week. (submitted by ElllPeaTea)

Varda’s next launch will use in-house spacecraft. Varda Space Industries is preparing to launch its fourth spacecraft, W-4, on a SpaceX rideshare mission scheduled to launch as soon as June 21 from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, Space News reports. The Los Angeles-based startup manufactures pharmaceuticals in orbit and returns them to Earth using specialized reentry capsules.

No longer using Rocket Lab… For its first three missions, Varda had partnered with Rocket Lab to use its Photon spacecraft for in-space operations. However, with W-4, Varda is debuting its first spacecraft built entirely in-house. The company is consolidating design and production internally in an effort to shorten the timeline between missions and increase flexibility to tailor vehicles to customer requirements. Varda decided that vertical integration was essential for scaling operations. (submitted by MarkW98)

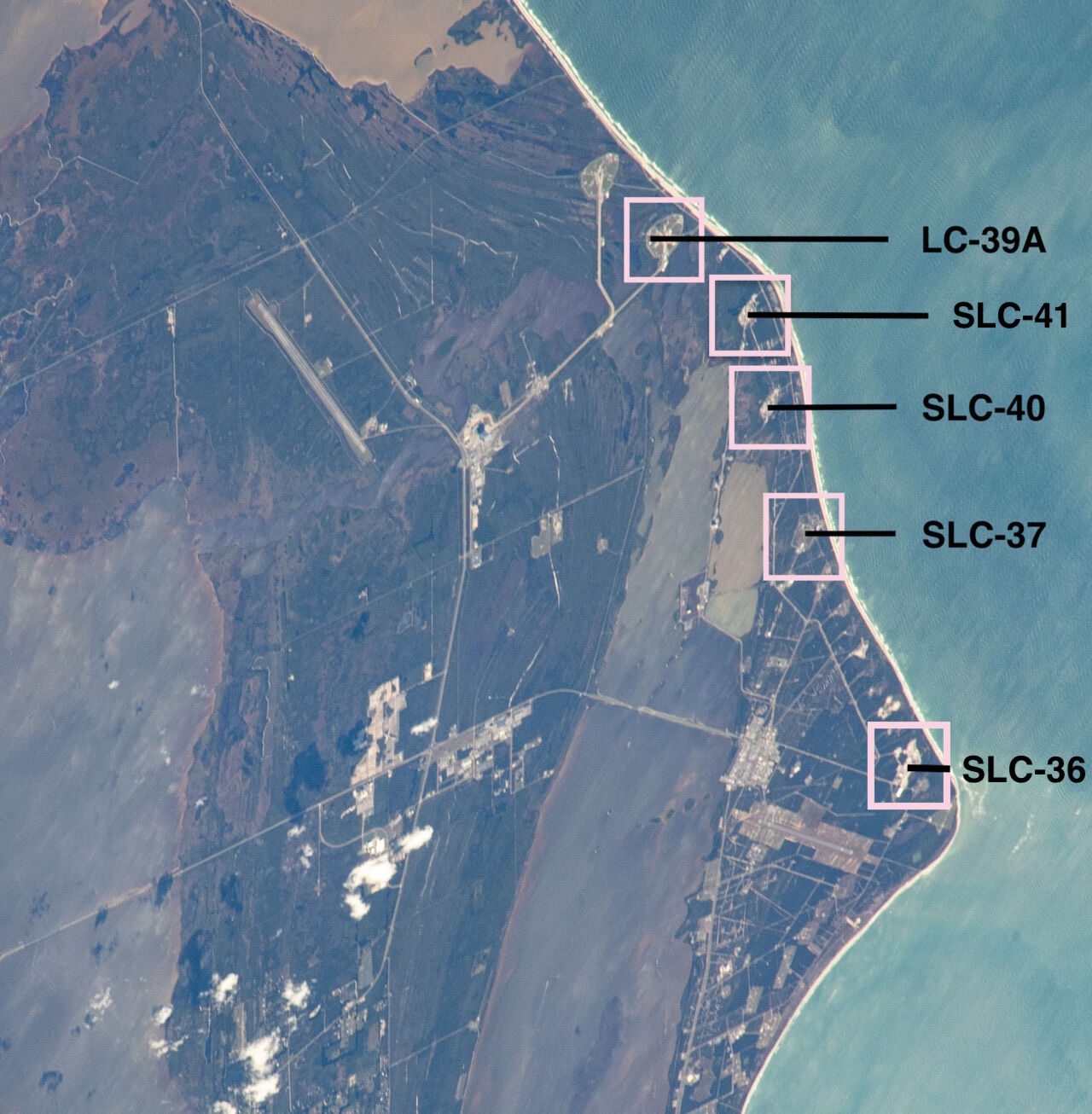

Vandenberg becomes SpaceX west. One of the defining events early in the history of SpaceX is when the company was effectively booted from Vandenberg Space Force Base in 2005 after completing the first successful test firing of the Falcon 1 rocket there. This set the company off on a long romp to Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean before acquiring a launch site at Cape Canaveral, Florida. When SpaceX finally returned to Vandenberg half a decade later, it had the Falcon 9 rocket and was no longer the scrappy upstart. Since then, it has made Vandenberg its own.

Falcons flying frequently… According to Spaceflight Now, on Monday, SpaceX launched the 200th overall orbital flight from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base, a batch of 26 Starlink V2 Mini satellites. Among the 199 previous orbital launches from SLC-4E, 131 of them were Falcon 9 rockets. The pad was first occupied by the Atlas-Agena rocket shortly after the Air Force Western Test Range activated in May 1964. SpaceX is currently going through the review process for acquiring SLC-6 as well to use for its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

China tests launch abort system. China carried out a successful pad abort test early Tuesday for its next-generation crew spacecraft for moon and low-Earth orbit missions, Space News reports. Footage of the test shows the escape system rapidly boosting the Mengzhou spacecraft away from the ground. Around 20 seconds later, the vehicle reached a predetermined altitude. The return capsule separated from the escape tower, and its parachutes deployed successfully. China is planning to conduct an in-flight escape test at maximum dynamic pressure later this year.

No longer reliant on the rocket… According to the agency, Mengzhou shifts from the traditional model of “rocket handles abort, spacecraft handles crew rescue,” as used by the Shenzhou, to a system where the Mengzhou spacecraft takes full responsibility for both abort control and crew safety. “The success of this test lays an important technical foundation for future crewed lunar missions,” a Chinese statement read. “Development work on related spacecraft, such as the Long March 10 launch vehicle and the lunar lander, is progressing steadily and will proceed to further testing as scheduled.” (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Another Starship explodes unexpectedly. SpaceX’s next Starship rocket exploded during a ground test in South Texas late Wednesday, dealing another blow to a program already struggling to overcome three consecutive failures in recent months, Ars reports. The late-night explosion at SpaceX’s rocket development complex in Starbase, Texas, destroyed the upper stage that was slated to launch on the next Starship test flight. The powerful blast set off fires around SpaceX’s Massey’s Test Site, located a few miles from the company’s Starship factory and launch pads.

A major anomaly … SpaceX confirmed the Starship, numbered Ship 36 in the company’s inventory, “experienced a major anomaly” on a test stand as the vehicle prepared to ignite its six Raptor engines for a static fire test. These hold-down test-firings are typically one of the final milestones in a Starship launch campaign before SpaceX moves the rocket to the launch pad. The company later said the failure may have been due to a composite overwrap pressure vessel, or COPV, near the top of the vehicle. On Thursday, aerial videos revealed that damage at the test site was significant but not beyond repair. (submitted by Tfargo04)

ArianeGroup will lead reusable engine project. The French space agency CNES announced Tuesday that it had selected ArianeGroup to lead a project to develop a high-thrust reusable rocket engine, European Spaceflight reports. The ASTRE (Advanced Staged-Combustion Technologies for Reusable Engines) project will also include contributions from SiriusSpace and Pangea Aerospace.

Company will take a test and learn approach… The project aims to develop a full-flow staged combustion methalox reusable rocket engine capable of producing between 200 and 300 tonnes of thrust, placing it in roughly the same class as the SpaceX Raptor engine. According to the agency, the goal of the project is “to equip the French and European space industry with new capabilities for strategic applications.” (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Next three launches

June 21: Falcon 9 | Transporter-14 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif. | 21: 19 UTC

June 22: Falcon 9 | Starlink 10-23 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 05: 47 UTC

June 23: Atlas V | Project Kuiper KA-02 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 10: 54 UTC

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

Rocket Report: Two big Asian reuse milestones, Vandenberg becomes SpaceX west Read More »