Clinical trial of a technique that could give everyone the best antibodies

If we ID the DNA for a great antibody, anyone can now make it.

One of the things that emerging diseases, including the COVID and Zika pandemics, have taught us is that it’s tough to keep up with infectious diseases in the modern world. Things like air travel can allow a virus to spread faster than our ability to develop therapies. But that doesn’t mean biotech has stood still; companies have been developing technologies that could allow us to rapidly respond to future threats.

There are a lot of ideas out there. But this week saw some early clinical trial results of one technique that could be useful for a range of infectious diseases. We’ll go over the results as a way to illustrate the sort of thinking that’s going on, along with the technologies we have available to pursue the resulting ideas.

The best antibodies

Any emerging disease leaves a mass of antibodies in its wake—those made by people in response to infections and vaccines, those made by lab animals we use to study the infectious agent, and so on. Some of these only have a weak affinity for the disease-causing agent, but some of them turn out to be what are called “broadly neutralizing.” These stick with high affinity not only to the original pathogen, but most or all of its variants, and possibly some related viruses.

Once an antibody latches on to a pathogen, broadly neutralizing antibodies inactivate it (as their name implies). This is typically because these antibodies bind to a site that’s necessary for a protein’s function. For example, broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV bind to the proteins that help this virus enter immune cells.

Unfortunately, not everyone develops broadly neutralizing antibodies, and certainly doesn’t do so in time to prevent infections. And we haven’t figured out a way of designing vaccinations that ensure their generation. So we’re often found ourselves stuck with knowing what antibodies we’d like to see people making while having no way of ensuring that they do.

One of the options we’ve developed is to just mass-produce broadly neutralizing antibodies and inject them into people. This has been approved for use against Ebola and provided an early treatment during the COVID pandemic. This approach has some practical limitations, though. For starters, the antibodies have a finite life span in the bloodstream, so injections may need to be repeated. In addition, making and purifying enough antibodies in bulk isn’t the easiest thing in the world, and they generally need to be kept refrigerated during the distribution, limiting the areas where they can be used.

So, a number of companies have been looking at an alternative: getting people to make their own. This could potentially lead to longer-lived protection, even ensuring the antibodies are present to block future infections if the DNA survives long enough.

Genes and volts

Once you identify cells that produce broadly neutralizing antibodies, it’s relatively simple to clone those genes and put them into a chunk of DNA that will ensure that they’ll be produced by any human cell. If we could get that DNA into a person’s cells, broadly neutralizing antibodies are the result. And a number of approaches have been tried to handle that “if.” Most of them have inserted the genes needed to make the antibodies into a harmless, non-infectious virus, and then injected that virus into volunteers. Unfortunately, these viruses have tended to set off a separate immune response, which causes more significant side effects and may limit how often this approach can be used.

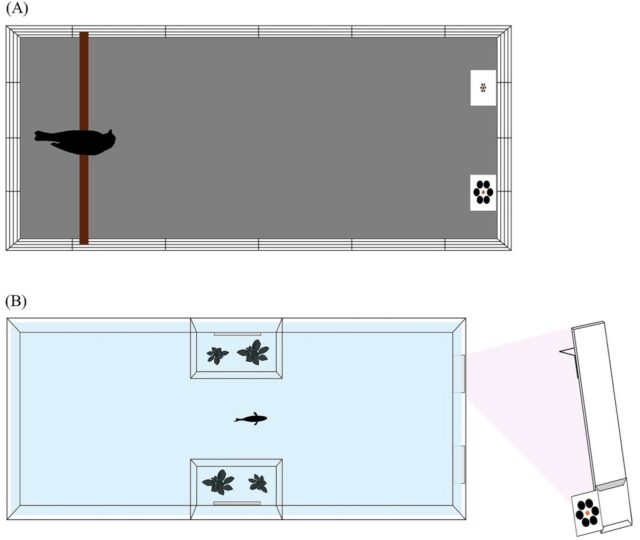

This brings us to the technique being used here. In this case, the researchers placed the antibody genes in a circular loop of DNA called a plasmid. This is enough to ensure that the DNA doesn’t get digested immediately and to get the antibody genes made into proteins. But it does nothing to help get the DNA inside of cells.

The research team, a mixture of people from a biotech company and academic labs, used a commercial injection setup that mixes the injection of the DNA with short pulses of electricity. The electricity disrupts the cell membrane, allowing the plasmid DNA to make it inside cells. Based on animal testing, doing this in muscle cells is enough to turn the muscles into factories producing lots of broadly neutralizing antibodies.

The new study was meant to test the safety of doing that in humans. The team recruited 44 participants, testing various doses of two antibody-producing plasmids and injection schedules. All but four of the subjects completed the study; three of those who dropped out had all been testing a routine with the electric pulses happening very quickly, which turned out to be unpleasant. Fortunately, it didn’t seem to make any difference to the production of antibodies.

While there were a lot of adverse reactions, most of these were associated with the injection itself: muscle pain at the site, a scab forming afterward, and a reddening of the skin. The worst problem appeared to be a single case of moderate muscle pain that persisted for a couple of days.

In all but one volunteer, the injection resulted in stable production of the two antibodies for at least 72 weeks following the injection; the single exception only made one of the two. That’s “at least” 72 weeks because that’s when they stopped testing—there was no indication that levels were dropping at this point. Injecting more DNA led to more variability in the amount of antibody produced, but that amount quickly maxed out. More total injections also boosted the level of antibody production. But even the minimal procedure—two injections of the lowest concentration tested—resulted in significant and stable antibodies.

And, as expected, these antibodies blocked the virus they were directed against: SARS-CoV-2.

The caveats

This approach seems to work—we can seemingly get anybody to make broadly neutralizing antibodies for months at a time. What’s the hitch? For starters, this isn’t necessarily great for a rapidly emerging pandemic. It takes a while to identify broadly neutralizing antibodies after a pathogen is identified. And, while it’s simple to ship DNA around the world to where it will be needed, injection setups that also produce the small electric pulses are not exactly standard equipment even in industrialized countries, much less the Global South.

Then there’s the issue of whether this really is a longer-term fix. Widespread use of broadly neutralizing antibodies will create a strong selective pressure for the evolution of variants that the antibody can no longer bind to. That may not always be a problem—broadly neutralizing antibodies generally bind to parts of proteins that are absolutely essential for the proteins’ function, and so it may not be possible to change those while maintaining the function. But that’s unlikely to always be the case.

In the end, however, social acceptance may end up being the biggest problem. People had an utter freakout over unfounded conspiracies that the RNA of COVID vaccines would somehow lead to permanent genetic changes. Presumably, having DNA that’s stable for months would be even harder for some segments of the public to swallow.

Nature Medicine, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-03969-0 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Clinical trial of a technique that could give everyone the best antibodies Read More »