Here’s how orbital dynamics wizardry helped save NASA’s next Mars mission

Blue Origin is counting down to launch of its second New Glenn rocket Sunday.

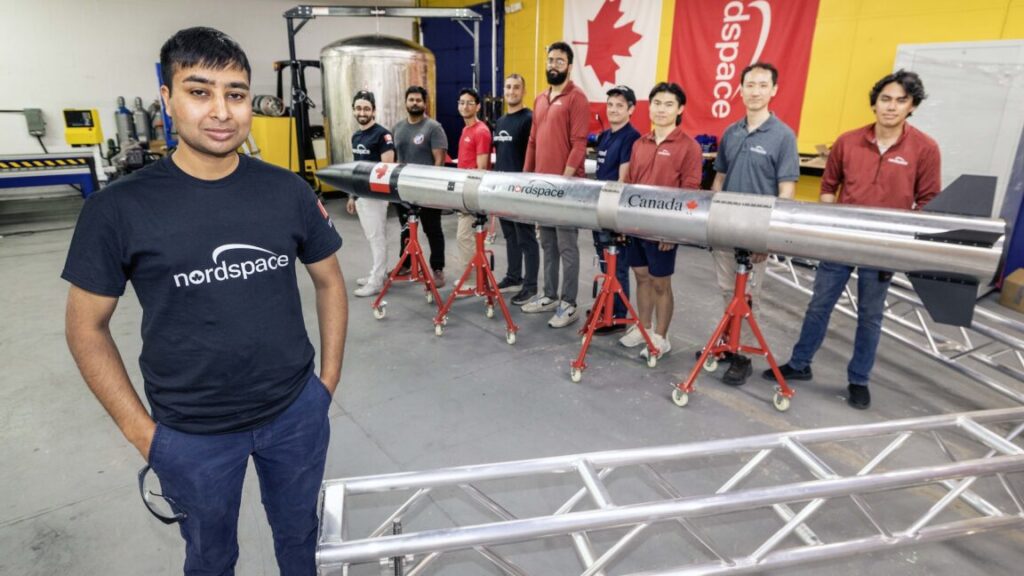

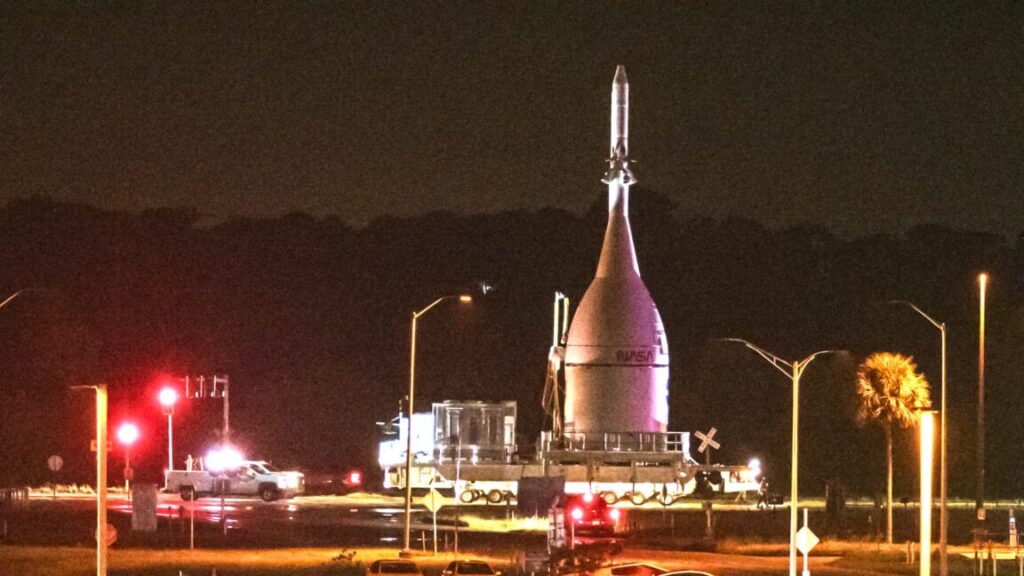

The New Glenn rocket rolls to Launch Complex-36 in preparation for liftoff this weekend. Credit: Blue Origin

CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida—The field of astrodynamics isn’t a magical discipline, but sometimes it seems trajectory analysts can pull a solution out of a hat.

That’s what it took to save NASA’s ESCAPADE mission from a lengthy delay, and possible cancellation, after its rocket wasn’t ready to send it toward Mars during its appointed launch window last year. ESCAPADE, short for Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers, consists of two identical spacecraft setting off for the red planet as soon as Sunday with a launch aboard Blue Origin’s massive New Glenn rocket.

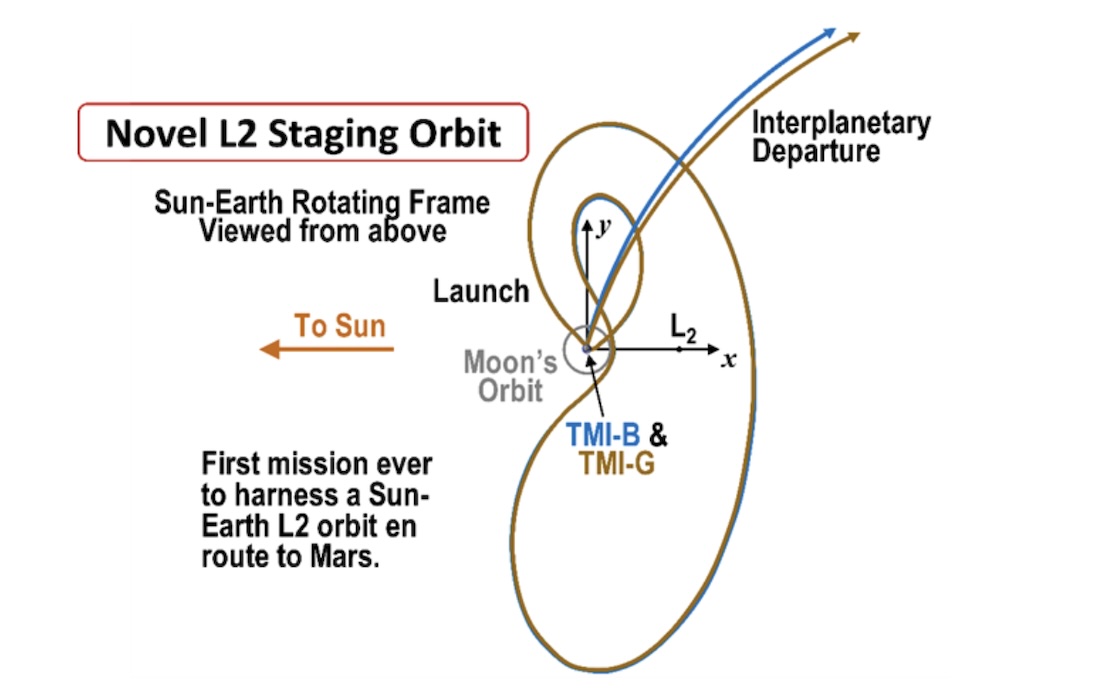

“ESCAPADE is pursuing a very unusual trajectory in getting to Mars,” said Rob Lillis, the mission’s principal investigator from the University of California, Berkeley. “We’re launching outside the typical Hohmann transfer windows, which occur every 25 or 26 months. We are using a very flexible mission design approach where we go into a loiter orbit around Earth in order to sort of wait until Earth and Mars are lined up correctly in November of next year to go to Mars.”

This wasn’t the original plan. When it was first designed, ESCAPADE was supposed to take a direct course from Earth to Mars, a transit that typically takes six to nine months. But ESCAPADE will now depart the Earth when Mars is more than 220 million miles away, on the opposite side of the Solar System.

The payload fairing of Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket, containing NASA’s two Mars-bound science probes. Credit: Blue Origin

The most recent Mars launch window was last year, and the next one doesn’t come until the end of 2026. The planets are not currently in alignment, and the proverbial stars didn’t align to get the ESCAPADE satellites and their New Glenn rocket to the launch pad until this weekend.

This is fine

But there are several reasons this is perfectly OK to NASA. The New Glenn rocket is overkill for this mission. The two-stage launcher could send many tons of cargo to Mars, but NASA is only asking it to dispatch about a ton of payload, comprising a pair of identical science probes designed to study how the planet’s upper atmosphere interacts with the solar wind.

But NASA got a good deal from Blue Origin. The space agency is paying Jeff Bezos’ space company about $20 million for the launch, less than it would for a dedicated launch on any other rocket capable of sending the ESCAPADE mission to Mars. In exchange, NASA is accepting a greater than usual chance of a launch failure. This is, after all, just the second flight of the 321-foot-tall (98-meter) New Glenn rocket, which hasn’t yet been certified by NASA or the US Space Force.

The ESCAPADE mission, itself, was developed with a modest budget, at least by the standards of interplanetary exploration. The mission’s total cost amounts to less than $80 million, an order of magnitude lower than all of NASA’s recent Mars missions. NASA officials would not entrust the second flight of the New Glenn rocket to launch a billion-dollar spacecraft, but the risk calculation changes as costs go down.

NASA knew all of this in 2023 when it signed a launch contract with Blue Origin for the ESCAPADE mission. What officials didn’t know was that the New Glenn rocket wouldn’t be ready to fly when ESCAPADE needed to launch in late 2024. It turned out Blue Origin didn’t launch the first New Glenn test flight until January of this year. It was a success. It took another 10 months for engineers to get the second New Glenn vehicle to the launch pad.

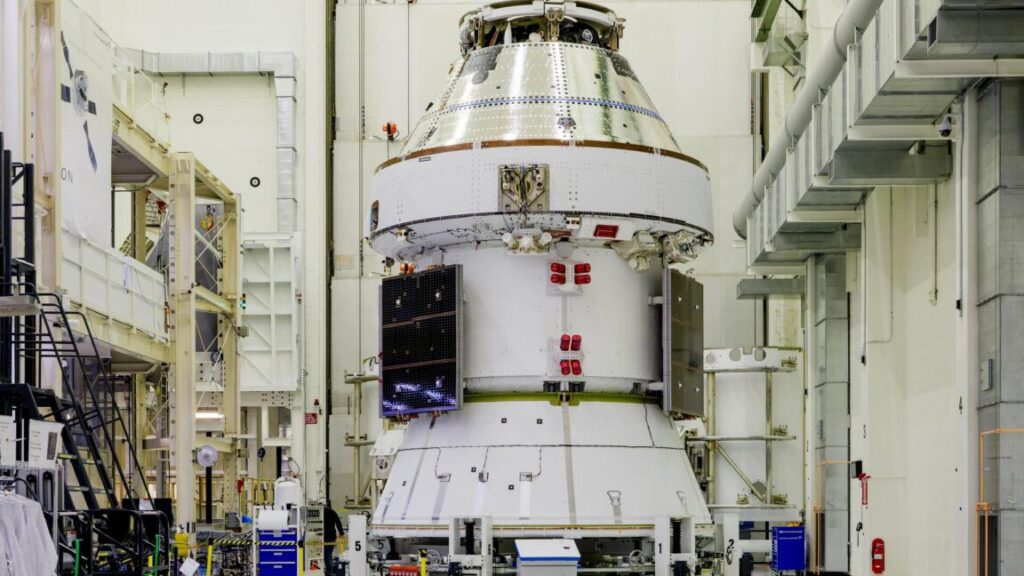

The twin ESCAPADE spacecraft undergoing final preparations for launch. Each spacecraft is about a half-ton fully fueled. Credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Aiming high

That’s where the rocket sits this weekend at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. If all goes according to plan, New Glenn will take off Sunday afternoon during an 88-minute launch window opening at 2: 45 pm EST (19: 45 UTC). There is a 65 percent chance of favorable weather, according to Blue Origin.

Blue Origin’s launch team, led by launch director Megan Lewis, will oversee the countdown Sunday. The rocket will be filled with super-cold liquid methane and liquid oxygen propellants beginning about four-and-a-half hours prior to liftoff. After some final technical and weather checks, the terminal countdown sequence will commence at T-minus 4 minutes, culminating in ignition of the rocket’s seven BE-4 main engines at T-minus 5.6 seconds.

The rocket’s flight computer will assess the health of each of the powerful engines, combining to generate more than 3.8 million pounds of thrust. If all looks good, hold-down restraints will release to allow the New Glenn rocket to begin its ascent from Florida’s Space Coast.

Heading east, the rocket will surpass the speed of sound in a little over a minute. After soaring through the stratosphere, New Glenn will shut down its seven booster engines and shed its first stage a little more than 3 minutes into the flight. Twin BE-3U engines, burning liquid hydrogen, will ignite to finish the job of sending the ESCAPADE satellites toward deep space. The rocket’s trajectory will send the satellites toward a gravitationally-stable location beyond the Moon, called the L2 Lagrange point, where it will swing into a loosely-bound loiter orbit to wait for the right time to head for Mars.

Meanwhile, the New Glenn booster, itself measuring nearly 20 stories tall, will begin maneuvers to head toward Blue Origin’s recovery ship floating a few hundred miles downrange in the Atlantic Ocean. The final part of the descent will include a landing burn using three of the BE-4 engines, then downshifting to a single engine to control the booster’s touchdown on the landing platform, dubbed “Jacklyn” in honor of Bezos’ late mother.

The launch timeline for New Glenn’s second mission. Credit: Blue Origin

New Glenn’s inaugural launch at the start of this year was a success, but the booster’s descent did not go well. The rocket was unable to restart its engines, and it crashed into the sea.

“We’ve incorporated a number of changes to our propellant management system, some minor hardware changes as well, to increase our likelihood of landing that booster on this mission,” said Laura Maginnis, Blue Origin’s vice president of New Glenn mission management. “That was the primary schedule driver that kind of took us from from January to where we are today.”

Blue Origin officials are hopeful they can land the booster this time. The company’s optimism is enough for officials to have penciled in a reflight of this particular booster on the very next New Glenn launch, slated for the early months of next year. That launch is due to send Blue Origin’s first Blue Moon cargo lander to the Moon.

“Our No. 1 objective is to deliver ESCAPADE safely and successfully on its way to L2, and then eventually on to Mars,” Maginnis said in a press conference Saturday. “We also are planning and wanting to land our booster. If we don’t land the booster, that’s OK. We have several more vehicles in production. We’re excited to see how the mission plays out tomorrow.”

Tracing a kidney bean

ESCAPADE’s path through space, relative to the Earth, has the peculiar shape of a kidney bean. In the world of astrodynamics, this is called a staging or libration orbit. It’s a way to keep the spacecraft on a stable trajectory to wait for the opportunity to go to Mars late next year.

“ESCAPADE has identified that this is the way that we want to fly, so we launch from Earth onto this kidney bean-shaped orbit,” said Jeff Parker, a mission designer from the Colorado-based company Advanced Space. “So, we can launch on virtually any day. What happens is that kidney bean just grows and shrinks based on how much time you need to spend in that orbit. So, we traverse that kidney bean and at the very end there’s a final little loop-the-loop that brings us down to Earth.”

That’s when the two ESCAPADE spacecraft, known as Blue and Gold, will pass a few hundred miles above our planet. At the right moment, on November 7 and 9 of next year, the satellites will fire their engines to set off for Mars.

An illustration of ESCAPADE’s trajectory to wait for the opportunity to go to Mars. Credit: UC-Berkeley

There are some tradeoffs with this unique staging orbit. It is riskier than the original plan of sending ESCAPADE straight to Mars. The satellites will be exposed to more radiation, and will consume more of their fuel just to get to the red planet, eating into reserves originally set aside for science observations.

The satellites were built by Rocket Lab, which designed them with extra propulsion capacity in order to accommodate launches on a variety of different rockets. In the end, NASA “judged that the risk for the mission was acceptable, but it certainly is higher risk,” said Richard French, Rocket Lab’s vice president of business development and strategy.

The upside of the tradeoff is it will demonstrate an “exciting and flexible way to get to Mars,” Lillis said. “In the future, if we’d like to send hundreds of spacecraft to Mars at once, it will be difficult to do that from just the launch pads we have on Earth within that month [of the interplanetary launch window]. We could potentially queue up spacecraft using the approach that ESCAPADE is pioneering.”

Here’s how orbital dynamics wizardry helped save NASA’s next Mars mission Read More »