Microsoft makes Zork I, II, and III open source under MIT License

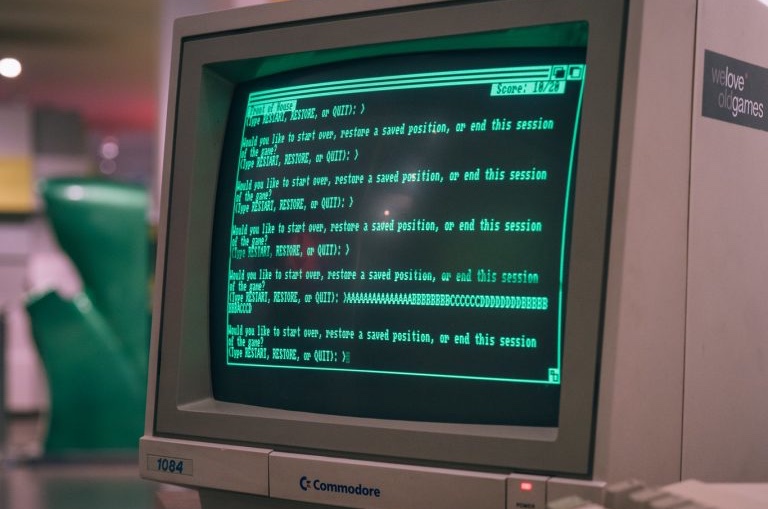

Zork, the classic text-based adventure game of incalculable influence, has been made available under the MIT License, along with the sequels Zork II and Zork III.

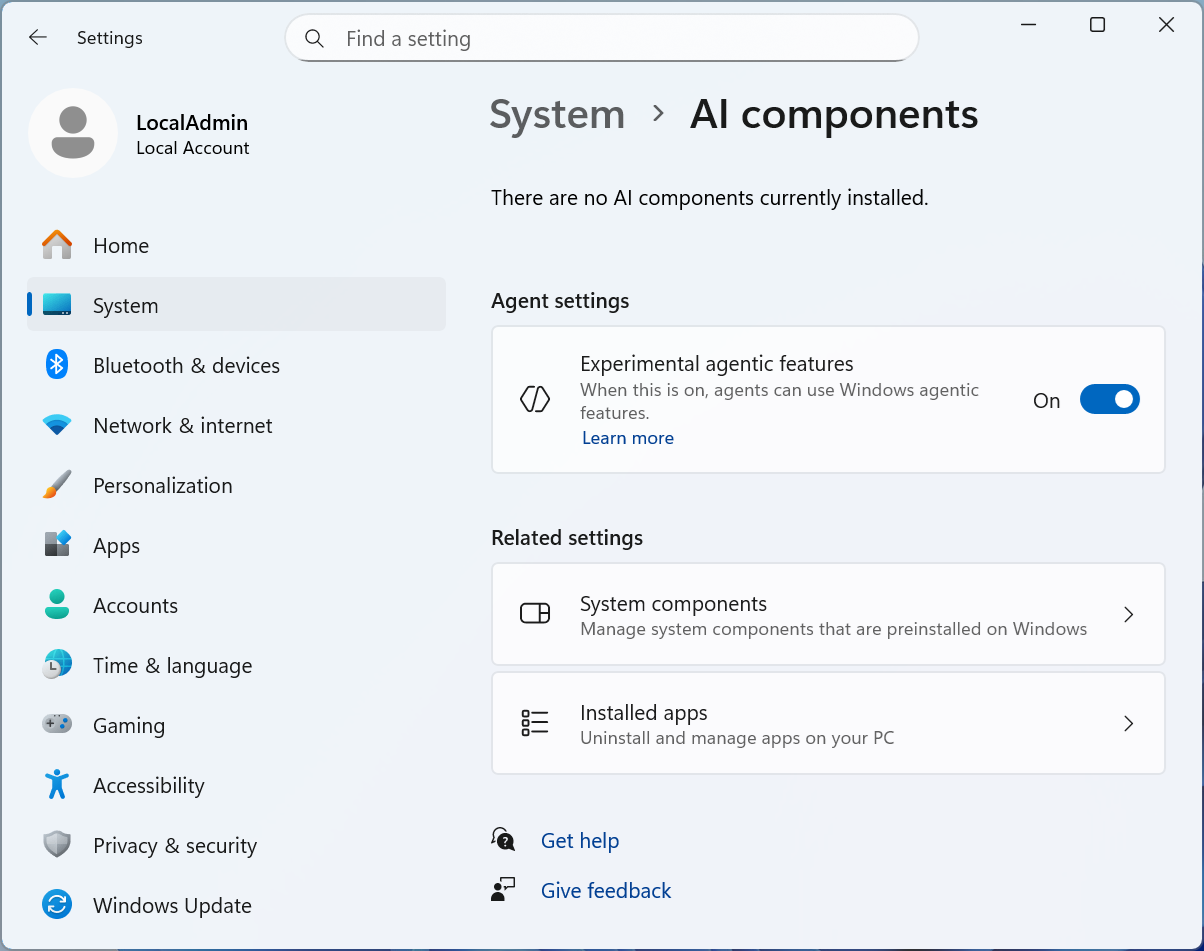

The move to take these Zork games open source comes as the result of the shared work of the Xbox and Activision teams along with Microsoft’s Open Source Programs Office (OSPO). Parent company Microsoft owns the intellectual property for the franchise.

Only the code itself has been made open source. Ancillary items like commercial packaging and marketing assets and materials remain proprietary, as do related trademarks and brands.

“Rather than creating new repositories, we’re contributing directly to history. In collaboration with Jason Scott, the well-known digital archivist of Internet Archive fame, we have officially submitted upstream pull requests to the historical source repositories of Zork I, Zork II, and Zork III. Those pull requests add a clear MIT LICENSE and formally document the open-source grant,” says the announcement co-written by Stacy Haffner (director of the OSPO at Microsoft) and Scott Hanselman (VP of Developer Community at the company).

Microsoft gained control of the Zork IP when it acquired Activision in 2022; Activision had come to own it when it acquired original publisher Infocom in the late ’80s. There was an attempt to sell Zork publishing rights directly to Microsoft even earlier in the ’80s, as founder Bill Gates was a big Zork fan, but it fell through, so it’s funny that it eventually ended up in the same place.

To be clear, this is not the first time the original Zork source code has been available to the general public. Scott uploaded it to GitHub in 2019, but the license situation was unresolved, and Activision or Microsoft could have issued a takedown request had they wished to.

Now that’s obviously not at risk of happening anymore.

Microsoft makes Zork I, II, and III open source under MIT License Read More »