Rocket Report: SpaceX’s dustup on the border; Northrop has a nozzle problem

NASA has finally test-fired the first of its new $100 million SLS rocket engines.

Backdropped by an offshore thunderstorm, a SpaceX Falcon 9 booster stands on its landing pad at Cape Canaveral after returning to Earth from a mission launching four astronauts to the International Space Station early Wednesday. Credit: SpaceX

Welcome to Edition 7.50 of the Rocket Report! We’re nearly halfway through the year, and it seems like a good time to look back on the past six months. What has been most surprising to me in the world of rockets? First, I didn’t expect SpaceX to have this much trouble with Starship Version 2. Growing pains are normal for new rockets, but I expected the next big hurdles for SpaceX to clear with Starship to be catching the ship from orbit and orbital refueling, not completing a successful launch. The state of Blue Origin’s New Glenn program is a little surprising to me. New Glenn’s first launch in January went remarkably well, beating the odds for a new rocket. Now, production delays are pushing back the next New Glenn flights. The flight of Honda’s reusable rocket hopper also came out of nowhere a few weeks ago.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Isar raises 150 million euros. German space startup Isar Aerospace has obtained 150 million euros ($175 million) in funding from an American investment company, Reuters reports. The company, which specializes in satellite launch services, signed an agreement for a convertible bond with Eldridge Industries, it said. Isar says it will use the funding to expand its launch service offerings. Isar’s main product is the Spectrum rocket, a two-stage vehicle designed to loft up to a metric ton (2,200 pounds) of payload mass to low-Earth orbit. Spectrum flew for the first time in March, but it failed moments after liftoff and fell back to the ground near its launch pad. Still, Isar became the first in a new crop of European launch startups to launch a rocket theoretically capable of reaching orbit.

Flush with cash … Isar is leading in another metric, too. The Munich-based company has now raised more than 550 million euros ($642 million) from venture capital investors and government-backed funds. This far exceeds the fundraising achievements of any other European launch startup. But the money will only go so far before Isar must prove it can successfully launch a rocket into orbit. Company officials have said they aim to launch the second Spectrum rocket before the end of this year. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Rocket Lab aiming for record turnaround. Rocket Lab demonstrated a notable degree of flexibility this week. Two light-class Electron rockets were nearing launch readiness at the company’s privately owned spaceport in New Zealand, but one of the missions encountered a technical problem, and Rocket Lab scrubbed a launch attempt Tuesday. The spaceport has two launch pads next to one another, so while technicians worked to fix that problem, Rocket Lab slotted in another Electron rocket to lift off from the pad next door. That mission, carrying a quartet of small commercial signals intelligence satellites for HawkEye 360, successfully launched Thursday.

Giving it another go … A couple of hours after that launch, Rocket Lab announced it was ready to try again with the mission it had grounded earlier in the week. “Can’t get enough of Electron missions? How about another one tomorrow? With our 67th mission complete, we’ve scheduled our next launch from LC-1 in less than 48 hours–Electron’s fastest turnaround from the same launch site yet!” Rocket Lab hasn’t disclosed what satellite is flying on this mission, citing the customer’s preference to remain anonymous for now.

You guessed it! Baguette One will launch from France. French rocket builder HyPrSpace will launch its Baguette One demonstrator from a missile testing site in mainland France, after signing an agreement with the country’s defense procurement agency, European Spaceflight reports. HyPrSpace was founded in 2019 to begin designing an orbital-class rocket named Orbital Baguette 1 (OB-1). The Baguette One vehicle is a subscale, single-stage suborbital demonstrator to prove out technologies for the larger satellite launcher, mainly its hybrid propulsion system.

Sovereign launch … HyPrSpace’s Baguette One will stand roughly 10 meters (30 feet) tall and will be capable of carrying payloads of up to 300 kilograms (660 pounds) to suborbital space. It is scheduled to launch next year from a French missile testing site in the south of France. “Gaining access to this dual-use launch pad in mainland France is a major achievement after many years of work on our hybrid propulsion technology,” said Sylvain Bataillard, director general of HyPrSpace. “It’s a unique opportunity for HyPrSpace and marks a decisive turning point. We’re eager to launch Baguette One and to play a key role in building a more sovereign, more sustainable, and boldly innovative European dual-use space industry.” (submitted by EllPeaTea)

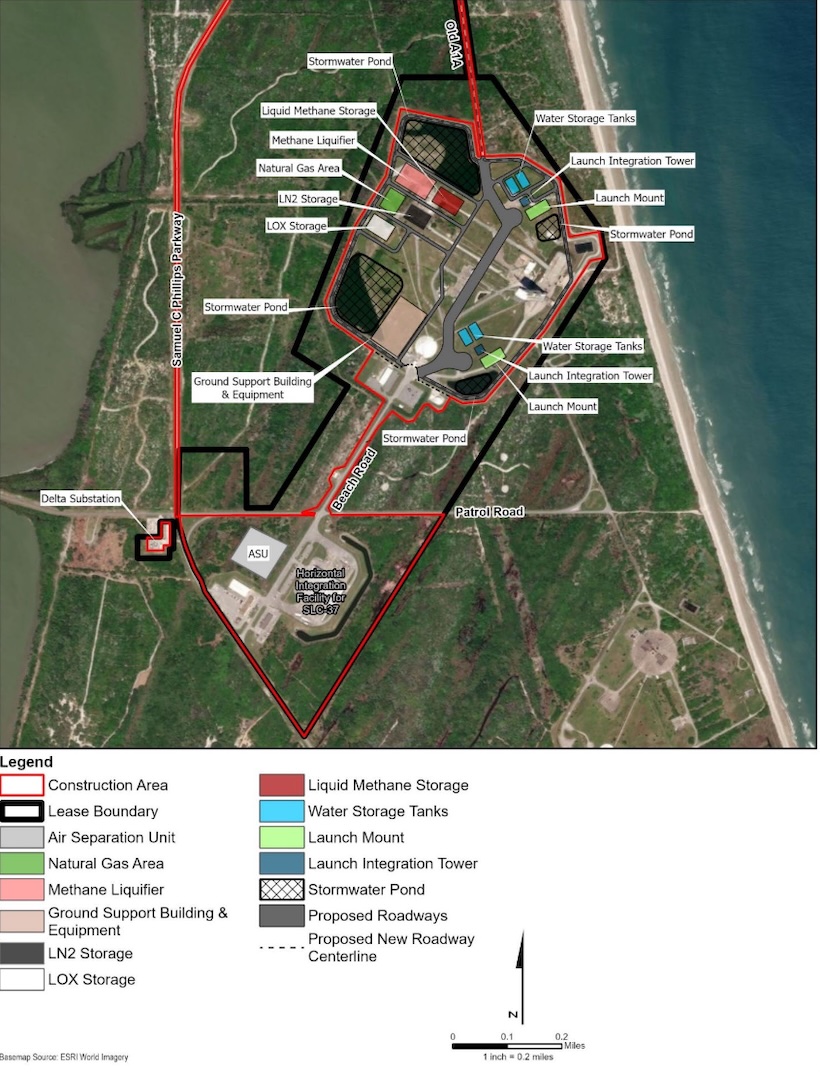

Firefly moves closer to launching from Sweden. An agreement between the United States and Sweden brings Firefly Aerospace one step closer to launching its Alpha rocket from a Swedish spaceport, Space News reports. The two countries signed a technology safeguards agreement (TSA) at a June 20 ceremony at the Swedish Embassy in Washington, DC. The TSA allows the export of American rockets to Sweden for launches there, putting in place measures to protect launch vehicle technology.

A special relationship … The US government has signed launch-related safeguard agreements with only a handful of countries, such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and now Sweden. Rocket exports are subject to strict controls because of the potential military applications of that technology. Firefly currently launches its Alpha rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, and is building a launch site at Wallops Island, Virginia. Firefly also has a lease for a launch pad at Cape Canaveral, Florida, although the company is prioritizing other sites. Then, last year, Firefly announced an agreement with the Swedish Space Corporation to launch Alpha from Esrange Space Center as soon as 2026. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

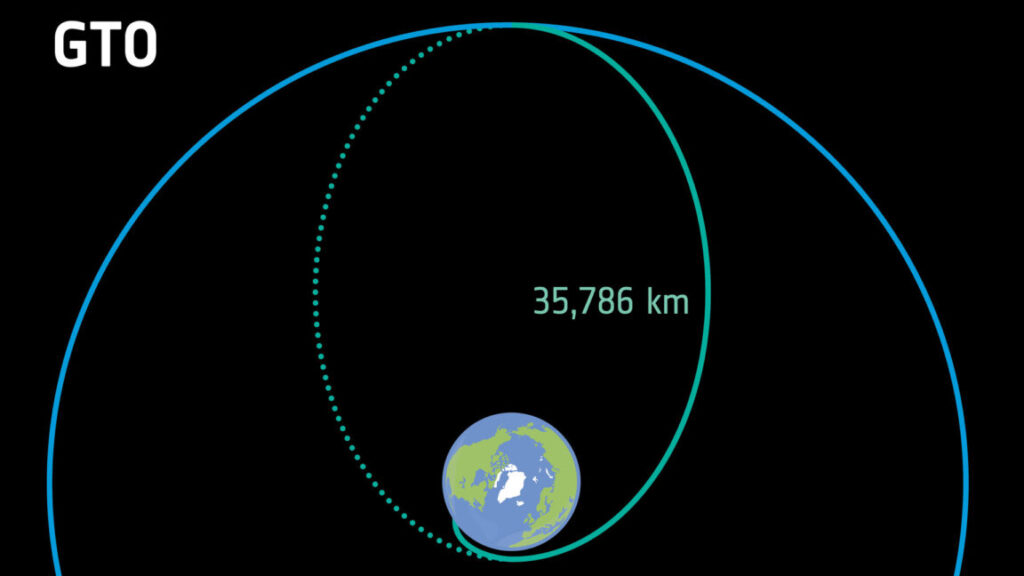

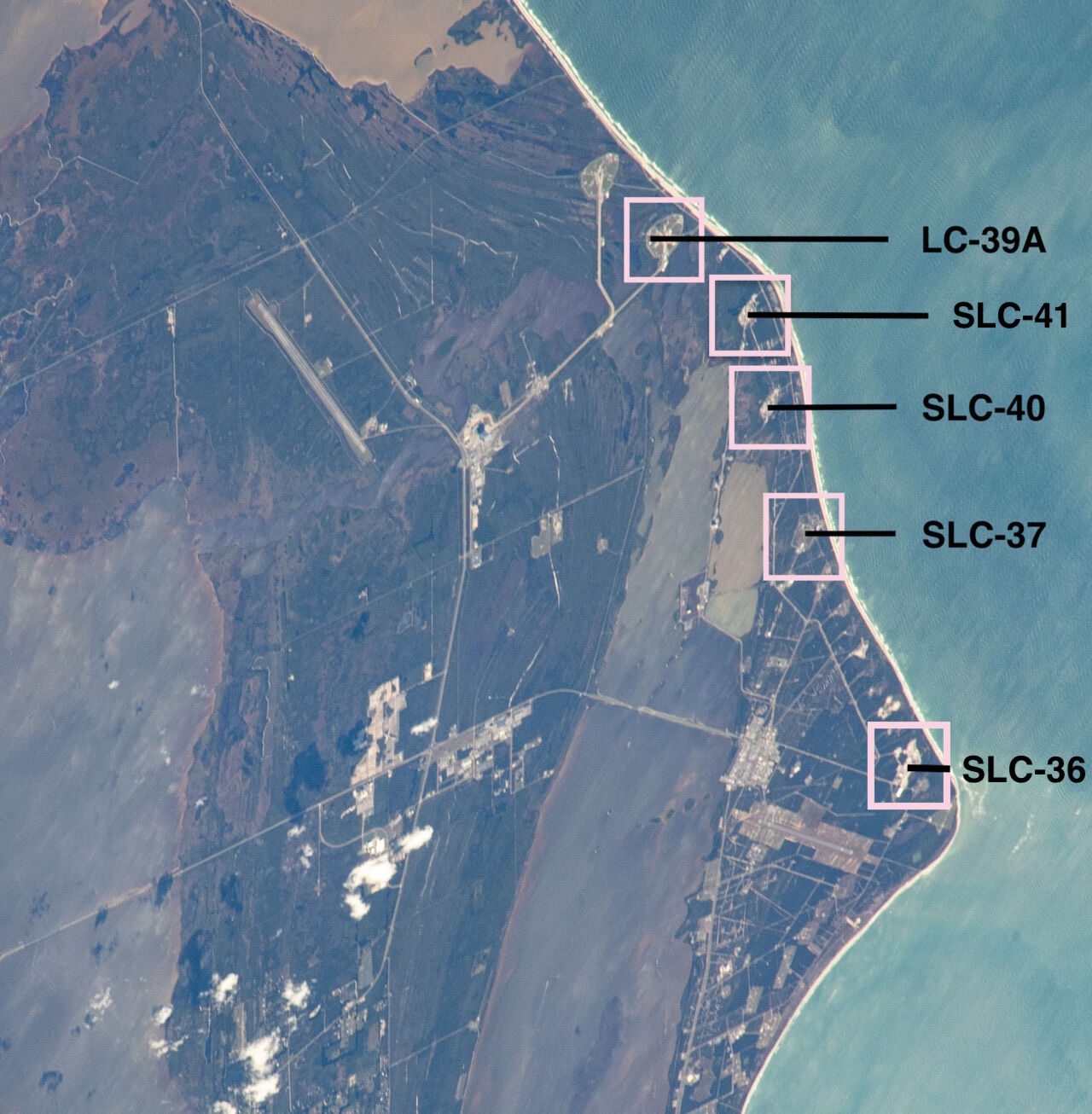

Amazon is running strong out of the gate. For the second time in two months, United Launch Alliance sent a batch of 27 broadband Internet satellites into orbit for Amazon on Monday morning, Ars reports. This was the second launch of a full load of operational satellites for Amazon’s Project Kuiper, a network envisioned to become a competitor to SpaceX’s Starlink. Just like the last flight on April 28, an Atlas V rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, and delivered Amazon’s satellites into an on-target orbit roughly 280 miles (450 kilometers) above Earth.

Time to put up or shut up … After lengthy production delays at Amazon’s satellite factory, the retail giant is finally churning out Kuiper satellites at scale. Amazon has already shipped the third batch of Kuiper satellites to Florida to prepare for launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket next month. ULA won the lion’s share of Amazon’s multibillion-dollar launch contract in 2022, committing to up to 38 Vulcan launches for Kuiper and nine Atlas V flights. Three of those Atlas Vs have now launched. Amazon also reserved 18 launches on Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket, and at least 12 on Blue Origin’s New Glenn. Vulcan, Ariane 6, and New Glenn have only flown one or two times, and Amazon is asking them to quickly ramp up their cadence to deliver 3,232 Kuiper satellites to orbit in the next few years. The handful of Falcon 9s and Atlas Vs that Amazon has on contract are the only rockets in the bunch with a proven track record. With Kuiper satellites now regularly shipping out of the factory, any blame for future delays may shift from Amazon to the relatively unproven rockets it has chosen to launch them.

Falcon 9 launches with four commercial astronauts. Retired astronaut Peggy Whitson, America’s most experienced space flier, and three rookie crewmates from India, Poland, and Hungary blasted off on a privately financed flight to the International Space Station early Wednesday, CBS News reports. This is the fourth non-government mission mounted by Houston-based Axiom Space. The four commercial astronauts rocketed into orbit on a SpaceX Falcon 9 launcher from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and their Dragon capsule docked at the space station Thursday to kick off a two-week stay.

A brand-new Dragon … The Crew Dragon spacecraft flown on this mission, serial number C213, is the fifth and final addition to SpaceX’s fleet of astronaut ferry ships built for NASA trips to the space station and for privately funded commercial missions to low-Earth orbit. Moments after reaching orbit Wednesday, Whitson revealed the name of the new spacecraft: Crew Dragon Grace. “We had an incredible ride uphill, and now we’d like to set our course for the International Space Station aboard the newest member of the Dragon fleet, our spacecraft named Grace. … Grace reminds us that spaceflight is not just a feat of engineering, but an act of goodwill to the benefit of every human everywhere.”

How soon until Ariane 6 is flying regularly? It’ll take several years for Arianespace to ramp up the launch cadence of Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket, Space News reports. David Cavaillolès, chief executive of Arianespace, addressed questions at the Paris Air Show about how quickly Arianespace can reach its target of launching 10 Ariane 6 rockets per year. “We need to go to 10 launches per year for Ariane 6 as soon as possible,” he said. “It’s twice as more as for Ariane 5, so it’s a big industrial change.” Two Ariane 6 rockets have launched so far, and a third mission is on track to lift off in August. Arianespace’s CEO reiterated earlier plans to conduct four more Ariane 6 launches through the end of this year, including the first flight of the more powerful Ariane 64 variant with four solid rocket boosters.

Not a heavy lift … Arianespace’s target flight rate of 10 Ariane 6 rockets per year is modest compared to other established companies with similarly sized launch vehicles. United Launch Alliance is seeking to launch as many as 25 Vulcan rockets per year. Blue Origin’s New Glenn is designed to eventually fly often, although the company hasn’t released a target launch cadence. SpaceX, meanwhile, aims to launch up to 170 Falcon 9 rockets this year. But European governments are perhaps more committed than ever to maintaining a sovereign launch capability for the continent, so Ariane 6 isn’t going away. Arianespace has sold more than 30 Ariane 6 launches, primarily to European institutional customers and Amazon.

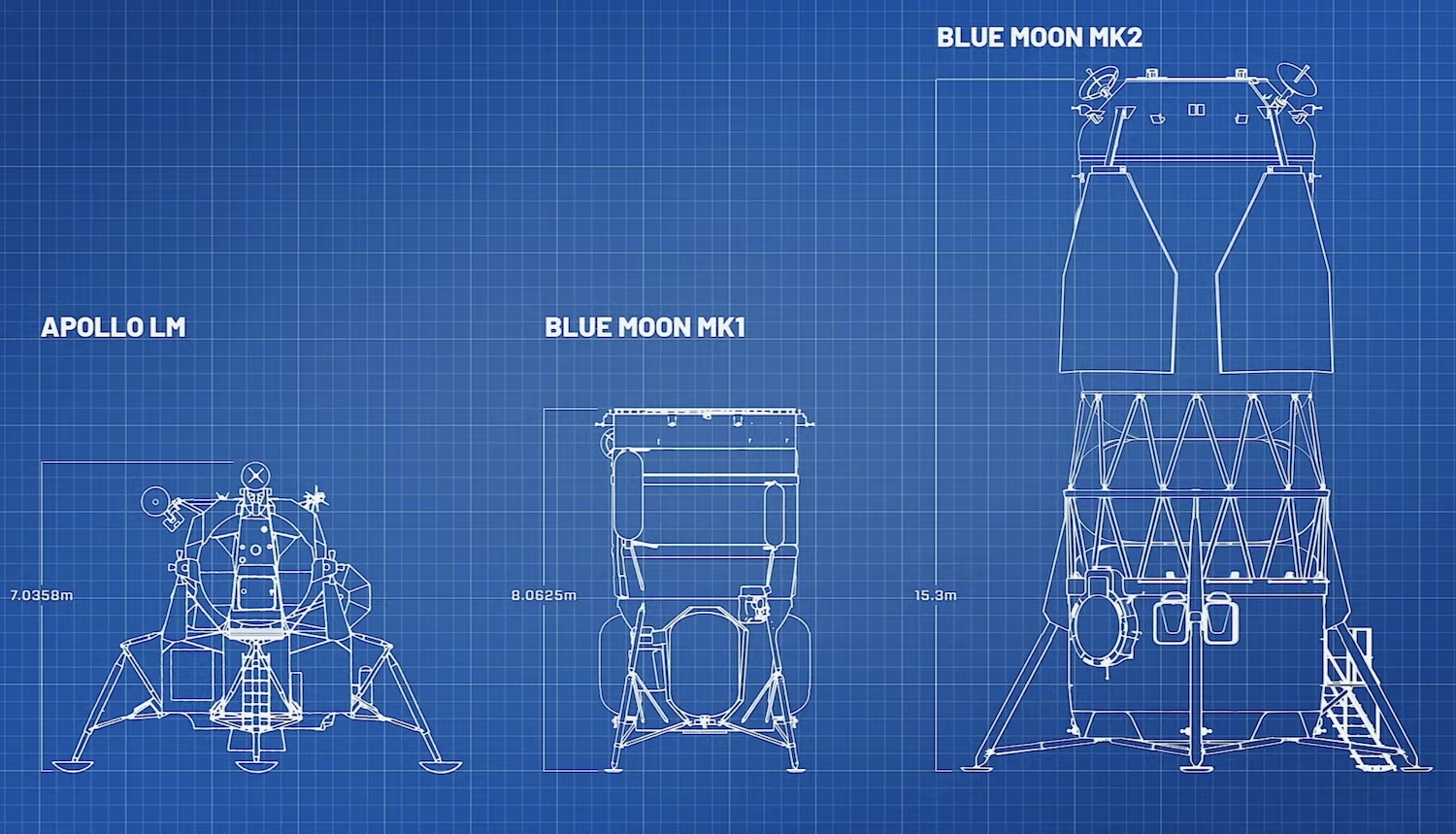

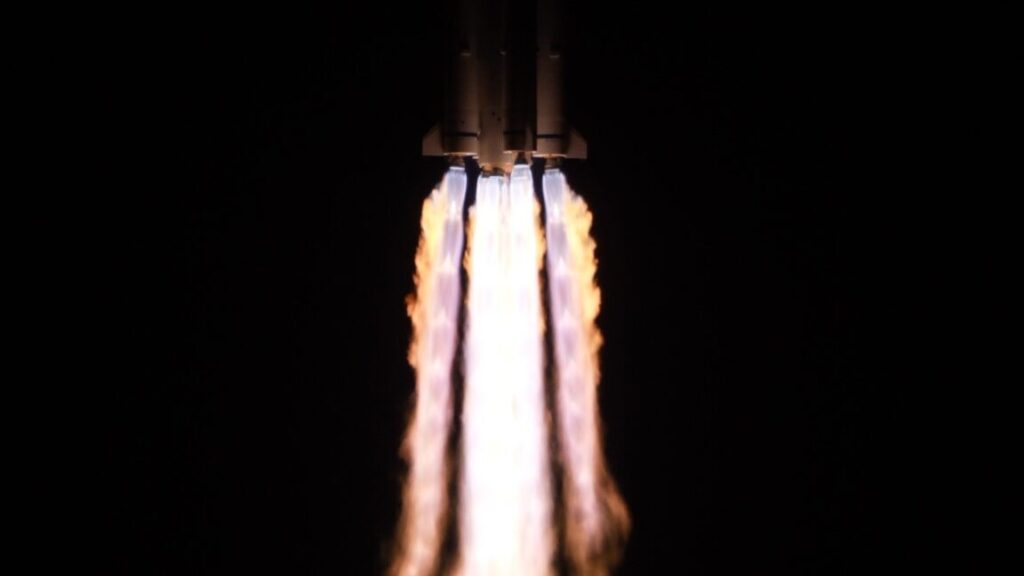

SLS booster blows its nozzle. NASA and Northrop Grumman test-fired a new solid rocket booster in Utah on Thursday, and it didn’t go exactly according to plan, Ars reports. This booster features a new design that NASA would use to power Space Launch System rockets, beginning with the ninth mission, or Artemis IX. The motor tested on Thursday isn’t flight-worthy. It’s a test unit that engineers will use to learn about the rocket’s performance. It turns out they did learn something, but perhaps not what they wanted. About 1 minute and 40 seconds into the booster’s burn, a fiery plume emerged from the motor’s structure just above its nozzle. Moments later, the nozzle violently disintegrated. The booster kept firing until it ran out of pre-packed solid propellant.

A questionable future … NASA’s Space Launch System appears to have a finite shelf life. The Trump administration wants to cancel it after just three launches, while the preliminary text of a bill making its way through Congress would extend it to five flights. But chances are low the Space Launch System will make it to nine flights, and if it does, it’s questionable if it would reach that point before 2040. The SLS rocket is a core piece of NASA’s plan to return US astronauts to the Moon under the Artemis program, but the White House seeks to cancel the program in favor of cheaper commercial alternatives.

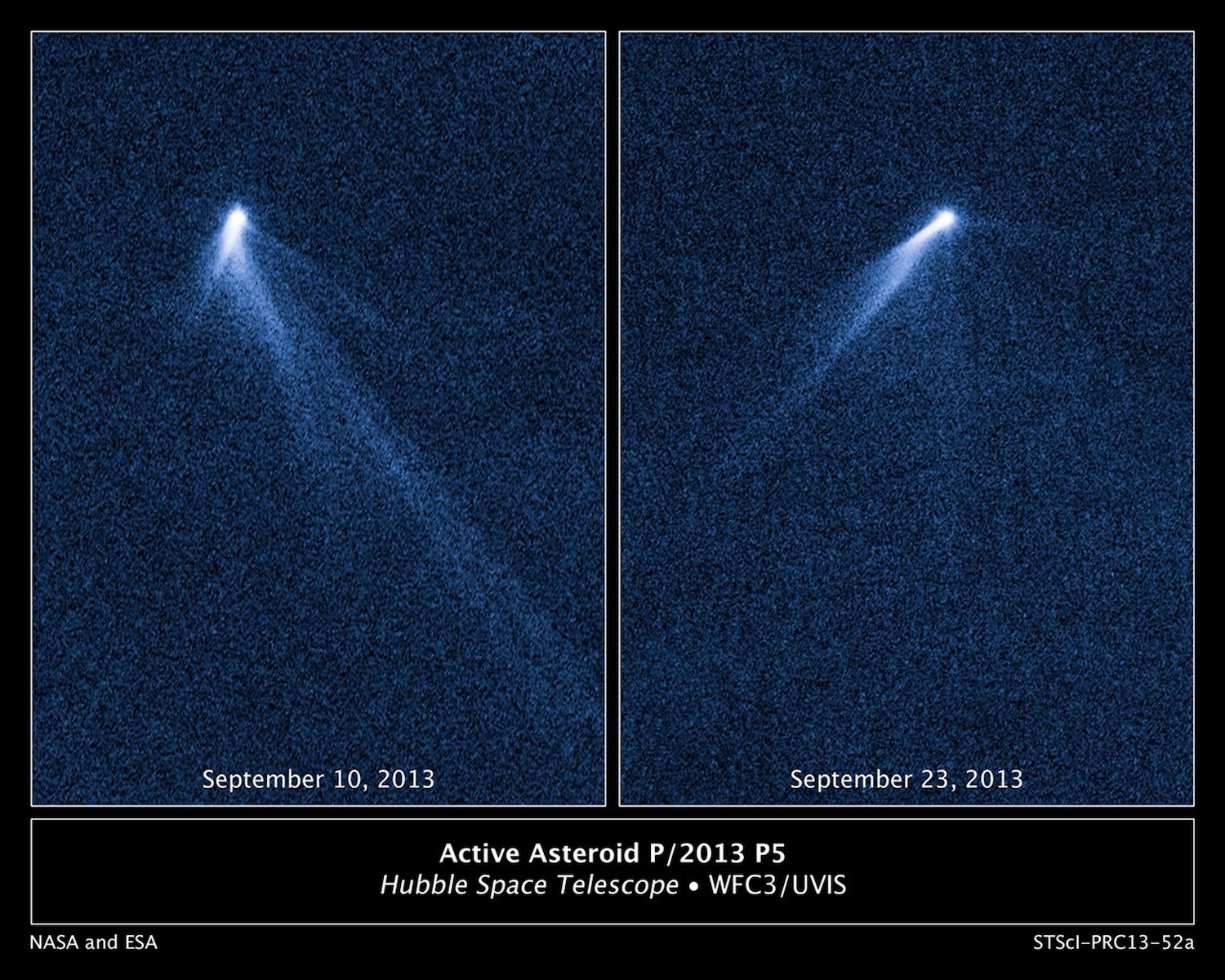

NASA conducts a low-key RS-25 engine test. The booster ground test on Thursday was the second time in less than a week that NASA test-fired new propulsion hardware for the Space Launch System. Last Friday, June 20, NASA ignited a new RS-25 engine on a test stand at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. The hydrogen-fueled engine is the first of its kind to be manufactured since the end of the space shuttle program. This particular RS-25 engine is assigned to power the fifth launch of the SLS rocket, a mission known as Artemis V, that may end up never flying. While NASA typically livestreams engine tests at Stennis, the agency didn’t publicize this event ahead of time.

It has been 10 years … The SLS rocket was designed to recycle leftover parts from the space shuttle program, but NASA will run out of RS-25 engines after the rocket’s fourth flight and will exhaust its inventory of solid rocket booster casings after the eighth flight. Recognizing that shuttle-era parts will eventually run out, NASA signed a contract with Aerojet Rocketdyne (now L3Harris) to set the stage for the production of new RS-25 engines in 2015. NASA later ordered an initial batch of six RS-25 engines from Aerojet, then added 18 more to the order in 2020, at a price of about $100 million per engine. Finally, a brand-new flight-worthy RS-25 engine has fired up on a test stand. If the Trump administration gets its way, these engines will never fly. Maybe that’s fine, but after so long with so much taxpayer investment, last week’s test milestone is worth publicizing, if not celebrating.

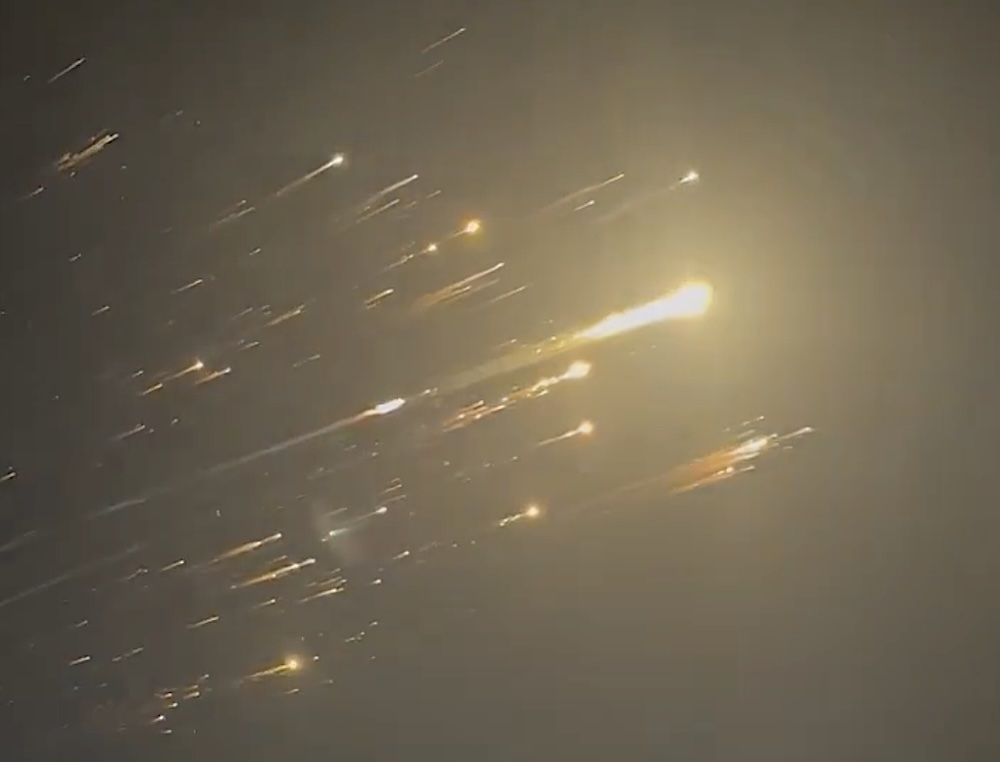

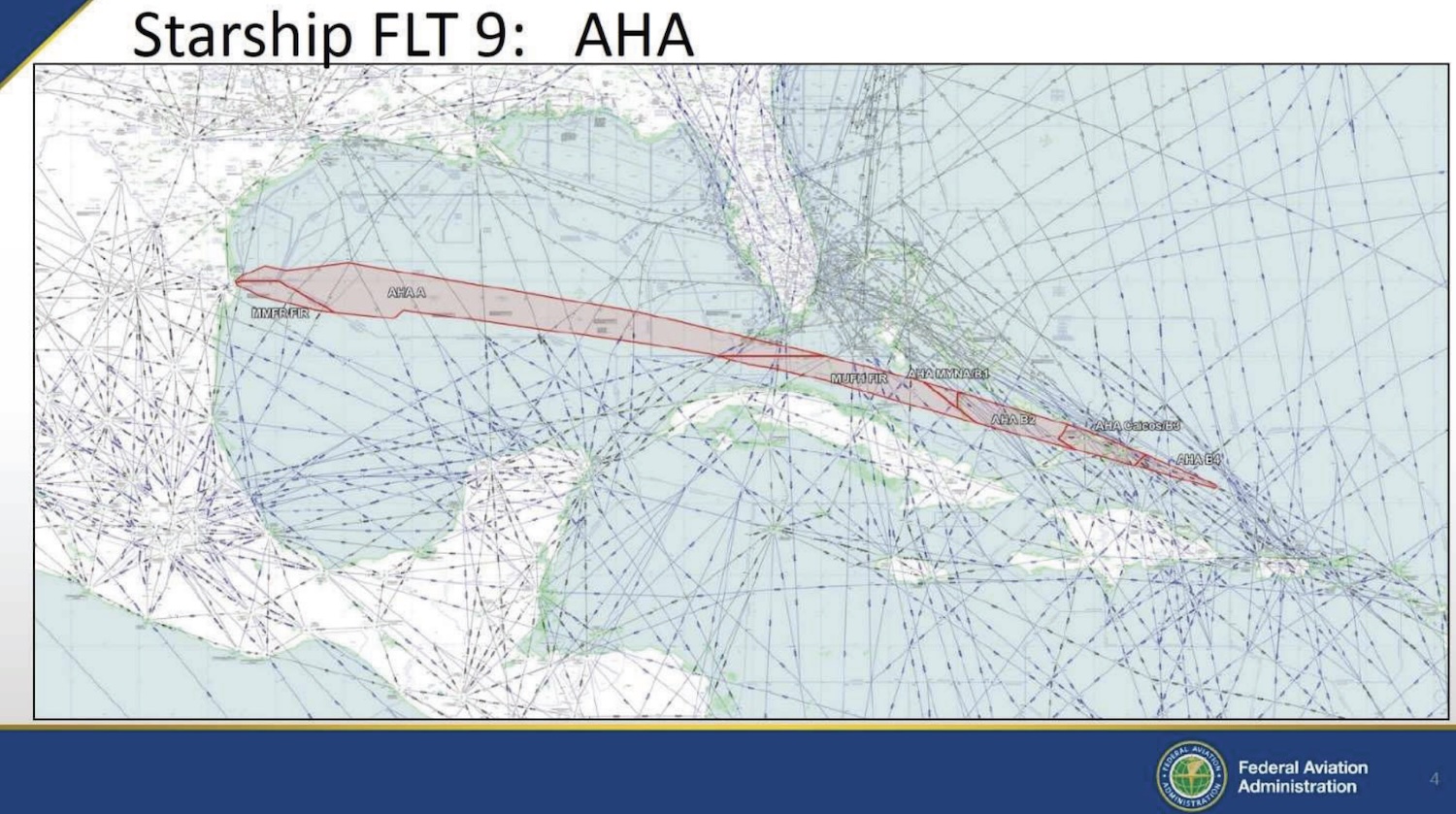

SpaceX finds itself in a dustup on the border. President Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico is considering taking legal action after one of SpaceX’s giant Starship rockets disintegrated in a giant fireball earlier this month as it was being fueled for a test-firing of its engines, The New York Times reports. No one was injured in the explosion, which rained debris on the beaches of the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas. The conflagration occurred at a test site SpaceX operates a few miles away from the Starship launch pad. This test facility is located next to the Rio Grande River, just a few hundred feet from Mexico. The power of the blast sent wreckage flying across the river onto Mexican territory.

Collision course …“We are reviewing everything related to the launching of rockets that are very close to our border,” Sheinbaum said at a news conference Wednesday. If SpaceX violated any international laws, she added, “we will file any necessary claims.” Sheinbaum’s leftist party holds enormous sway around Mexico, and the Times reports she was responding to calls to take action against SpaceX amid a growing outcry among scientists, regional officials and environmental activists over the impact that the company’s operations are having on Mexican ecosystems. SpaceX, on the other hand, said its efforts to recover debris from the Starship explosion have been “hindered by unauthorized parties trespassing on private property.” SpaceX said it requested assistance from the government of Mexico in the recovery, and added that it offered its own resources to help in the clean-up.

Next three launches

June 28: Falcon 9 | Starlink 10-34 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 04: 26 UTC

June 28: Electron | “Symphony in the Stars” | Māhia Peninsula, New Zealand | 06: 45 UTC

June 28: H-IIA | GOSAT-GW | Tanegashima Space Center, Japan | 16: 33 UTC

Rocket Report: SpaceX’s dustup on the border; Northrop has a nozzle problem Read More »