iOS and Android juice jacking defenses have been trivial to bypass for years

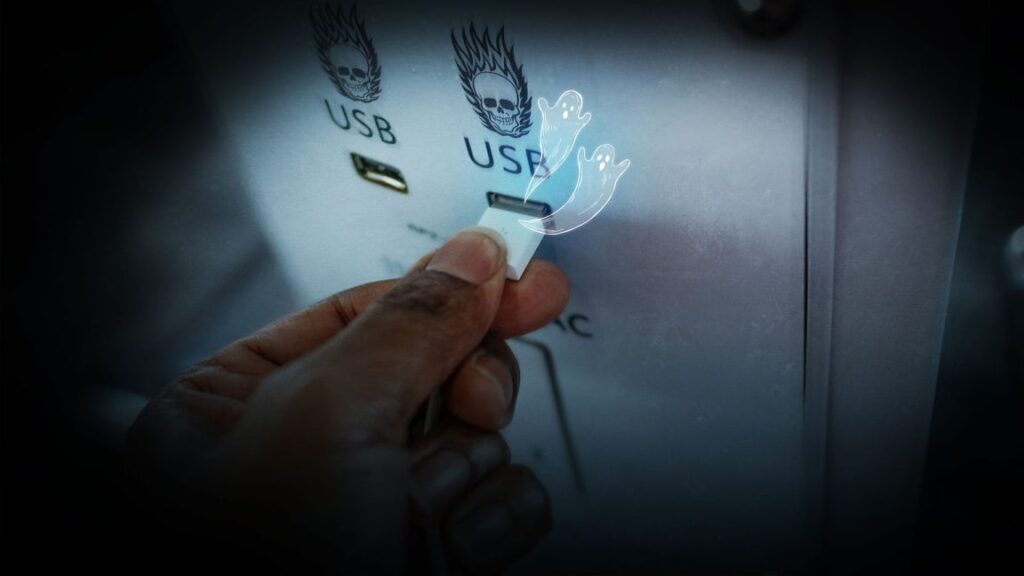

About a decade ago, Apple and Google started updating iOS and Android, respectively, to make them less susceptible to “juice jacking,” a form of attack that could surreptitiously steal data or execute malicious code when users plug their phones into special-purpose charging hardware. Now, researchers are revealing that, for years, the mitigations have suffered from a fundamental defect that has made them trivial to bypass.

“Juice jacking” was coined in a 2011 article on KrebsOnSecurity detailing an attack demonstrated at a Defcon security conference at the time. Juice jacking works by equipping a charger with hidden hardware that can access files and other internal resources of phones, in much the same way that a computer can when a user connects it to the phone.

An attacker would then make the chargers available in airports, shopping malls, or other public venues for use by people looking to recharge depleted batteries. While the charger was ostensibly only providing electricity to the phone, it was also secretly downloading files or running malicious code on the device behind the scenes. Starting in 2012, both Apple and Google tried to mitigate the threat by requiring users to click a confirmation button on their phones before a computer—or a computer masquerading as a charger—could access files or execute code on the phone.

The logic behind the mitigation was rooted in a key portion of the USB protocol that, in the parlance of the specification, dictates that a USB port can facilitate a “host” device or a “peripheral” device at any given time, but not both. In the context of phones, this meant they could either:

- Host the device on the other end of the USB cord—for instance, if a user connects a thumb drive or keyboard. In this scenario, the phone is the host that has access to the internals of the drive, keyboard or other peripheral device.

- Act as a peripheral device that’s hosted by a computer or malicious charger, which under the USB paradigm is a host that has system access to the phone.

An alarming state of USB security

Researchers at the Graz University of Technology in Austria recently made a discovery that completely undermines the premise behind the countermeasure: They’re rooted under the assumption that USB hosts can’t inject input that autonomously approves the confirmation prompt. Given the restriction against a USB device simultaneously acting as a host and peripheral, the premise seemed sound. The trust models built into both iOS and Android, however, present loopholes that can be exploited to defeat the protections. The researchers went on to devise ChoiceJacking, the first known attack to defeat juice-jacking mitigations.

“We observe that these mitigations assume that an attacker cannot inject input events while establishing a data connection,” the researchers wrote in a paper scheduled to be presented in August at the Usenix Security Symposium in Seattle. “However, we show that this assumption does not hold in practice.”

The researchers continued:

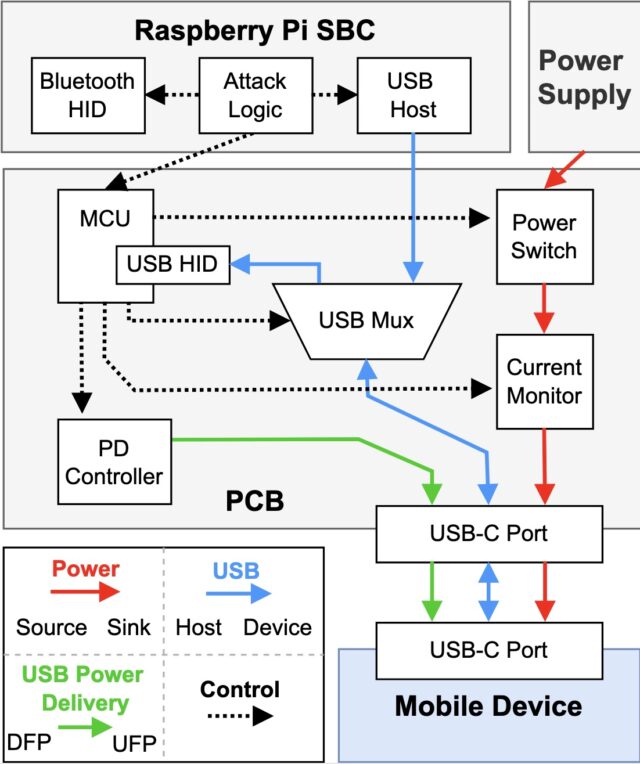

We present a platform-agnostic attack principle and three concrete attack techniques for Android and iOS that allow a malicious charger to autonomously spoof user input to enable its own data connection. Our evaluation using a custom cheap malicious charger design reveals an alarming state of USB security on mobile platforms. Despite vendor customizations in USB stacks, ChoiceJacking attacks gain access to sensitive user files (pictures, documents, app data) on all tested devices from 8 vendors including the top 6 by market share.

In response to the findings, Apple updated the confirmation dialogs in last month’s release of iOS/iPadOS 18.4 to require a user authentication in the form of a PIN or password. While the researchers were investigating their ChoiceJacking attacks last year, Google independently updated its confirmation with the release of version 15 in November. The researchers say the new mitigation works as expected on fully updated Apple and Android devices. Given the fragmentation of the Android ecosystem, however, many Android devices remain vulnerable.

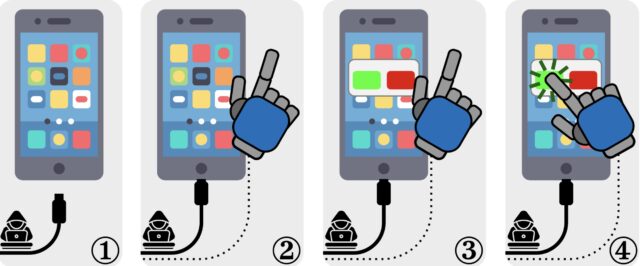

All three of the ChoiceJacking techniques defeat Android juice-jacking mitigations. One of them also works against those defenses in Apple devices. In all three, the charger acts as a USB host to trigger the confirmation prompt on the targeted phone.

The attacks then exploit various weaknesses in the OS that allow the charger to autonomously inject “input events” that can enter text or click buttons presented in screen prompts as if the user had done so directly into the phone. In all three, the charger eventually gains two conceptual channels to the phone: (1) an input one allowing it to spoof user consent and (2) a file access connection that can steal files.

An illustration of ChoiceJacking attacks. (1) The victim device is attached to the malicious charger. (2) The charger establishes an extra input channel. (3) The charger initiates a data connection. User consent is needed to confirm it. (4) The charger uses the input channel to spoof user consent. Credit: Draschbacher et al.

It’s a keyboard, it’s a host, it’s both

In the ChoiceJacking variant that defeats both Apple- and Google-devised juice-jacking mitigations, the charger starts as a USB keyboard or a similar peripheral device. It sends keyboard input over USB that invokes simple key presses, such as arrow up or down, but also more complex key combinations that trigger settings or open a status bar.

The input establishes a Bluetooth connection to a second miniaturized keyboard hidden inside the malicious charger. The charger then uses the USB Power Delivery, a standard available in USB-C connectors that allows devices to either provide or receive power to or from the other device, depending on messages they exchange, a process known as the USB PD Data Role Swap.

A simulated ChoiceJacking charger. Bidirectional USB lines allow for data role swaps. Credit: Draschbacher et al.

With the charger now acting as a host, it triggers the file access consent dialog. At the same time, the charger still maintains its role as a peripheral device that acts as a Bluetooth keyboard that approves the file access consent dialog.

The full steps for the attack, provided in the Usenix paper, are:

1. The victim device is connected to the malicious charger. The device has its screen unlocked.

2. At a suitable moment, the charger performs a USB PD Data Role (DR) Swap. The mobile device now acts as a USB host, the charger acts as a USB input device.

3. The charger generates input to ensure that BT is enabled.

4. The charger navigates to the BT pairing screen in the system settings to make the mobile device discoverable.

5. The charger starts advertising as a BT input device.

6. By constantly scanning for newly discoverable Bluetooth devices, the charger identifies the BT device address of the mobile device and initiates pairing.

7. Through the USB input device, the charger accepts the Yes/No pairing dialog appearing on the mobile device. The Bluetooth input device is now connected.

8. The charger sends another USB PD DR Swap. It is now the USB host, and the mobile device is the USB device.

9. As the USB host, the charger initiates a data connection.

10. Through the Bluetooth input device, the charger confirms its own data connection on the mobile device.

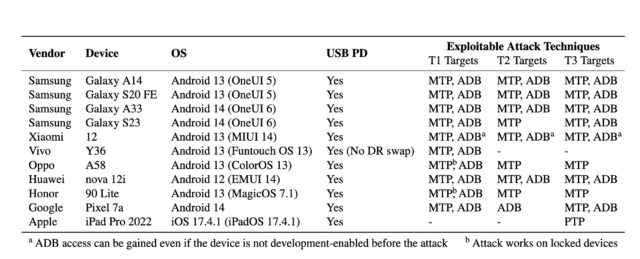

This technique works against all but one of the 11 phone models tested, with the holdout being an Android device running the Vivo Funtouch OS, which doesn’t fully support the USB PD protocol. The attacks against the 10 remaining models take about 25 to 30 seconds to establish the Bluetooth pairing, depending on the phone model being hacked. The attacker then has read and write access to files stored on the device for as long as it remains connected to the charger.

Two more ways to hack Android

The two other members of the ChoiceJacking family work only against the juice-jacking mitigations that Google put into Android. In the first, the malicious charger invokes the Android Open Access Protocol, which allows a USB host to act as an input device when the host sends a special message that puts it into accessory mode.

The protocol specifically dictates that while in accessory mode, a USB host can no longer respond to other USB interfaces, such as the Picture Transfer Protocol for transferring photos and videos and the Media Transfer Protocol that enables transferring files in other formats. Despite the restriction, all of the Android devices tested violated the specification by accepting AOAP messages sent, even when the USB host hadn’t been put into accessory mode. The charger can exploit this implementation flaw to autonomously complete the required user confirmations.

The remaining ChoiceJacking technique exploits a race condition in the Android input dispatcher by flooding it with a specially crafted sequence of input events. The dispatcher puts each event into a queue and processes them one by one. The dispatcher waits for all previous input events to be fully processed before acting on a new one.

“This means that a single process that performs overly complex logic in its key event handler will delay event dispatching for all other processes or global event handlers,” the researchers explained.

They went on to note, “A malicious charger can exploit this by starting as a USB peripheral and flooding the event queue with a specially crafted sequence of key events. It then switches its USB interface to act as a USB host while the victim device is still busy dispatching the attacker’s events. These events therefore accept user prompts for confirming the data connection to the malicious charger.”

The Usenix paper provides the following matrix showing which devices tested in the research are vulnerable to which attacks.

The susceptibility of tested devices to all three ChoiceJacking attack techniques. Credit: Draschbacher et al.

User convenience over security

In an email, the researchers said that the fixes provided by Apple and Google successfully blunt ChoiceJacking attacks in iPhones, iPads, and Pixel devices. Many Android devices made by other manufacturers, however, remain vulnerable because they have yet to update their devices to Android 15. Other Android devices—most notably those from Samsung running the One UI 7 software interface—don’t implement the new authentication requirement, even when running on Android 15. The omission leaves these models vulnerable to ChoiceJacking. In an email, principal paper author Florian Draschbacher wrote:

The attack can therefore still be exploited on many devices, even though we informed the manufacturers about a year ago and they acknowledged the problem. The reason for this slow reaction is probably that ChoiceJacking does not simply exploit a programming error. Rather, the problem is more deeply rooted in the USB trust model of mobile operating systems. Changes here have a negative impact on the user experience, which is why manufacturers are hesitant. [It] means for enabling USB-based file access, the user doesn’t need to simply tap YES on a dialog but additionally needs to present their unlock PIN/fingerprint/face. This inevitably slows down the process.

The biggest threat posed by ChoiceJacking is to Android devices that have been configured to enable USB debugging. Developers often turn on this option so they can troubleshoot problems with their apps, but many non-developers enable it so they can install apps from their computer, root their devices so they can install a different OS, transfer data between devices, and recover bricked phones. Turning it on requires a user to flip a switch in Settings > System > Developer options.

If a phone has USB Debugging turned on, ChoiceJacking can gain shell access through the Android Debug Bridge. From there, an attacker can install apps, access the file system, and execute malicious binary files. The level of access through the Android Debug Mode is much higher than that through Picture Transfer Protocol and Media Transfer Protocol, which only allow read and write access to system files.

The vulnerabilities are tracked as:

-

- CVE-2025-24193 (Apple)

- CVE-2024-43085 (Google)

- CVE-2024-20900 (Samsung)

- CVE-2024-54096 (Huawei)

A Google spokesperson confirmed that the weaknesses were patched in Android 15 but didn’t speak to the base of Android devices from other manufacturers, who either don’t support the new OS or the new authentication requirement it makes possible. Apple declined to comment for this post.

Word that juice-jacking-style attacks are once again possible on some Android devices and out-of-date iPhones is likely to breathe new life into the constant warnings from federal authorities, tech pundits, news outlets, and local and state government agencies that phone users should steer clear of public charging stations.

As I reported in 2023, these warnings are mostly scaremongering, and the advent of ChoiceJacking does little to change that, given that there are no documented cases of such attacks in the wild. That said, people using Android devices that don’t support Google’s new authentication requirement may want to refrain from public charging.

Dan Goodin is Senior Security Editor at Ars Technica, where he oversees coverage of malware, computer espionage, botnets, hardware hacking, encryption, and passwords. In his spare time, he enjoys gardening, cooking, and following the independent music scene. Dan is based in San Francisco. Follow him at here on Mastodon and here on Bluesky. Contact him on Signal at DanArs.82.

iOS and Android juice jacking defenses have been trivial to bypass for years Read More »