Google releases Gemini 3 Flash, promising improved intelligence and efficiency

Google began its transition to Gemini 3 a few weeks ago with the launch of the Pro model, and the arrival of Gemini 3 Flash kicks it into high gear. The new, faster Gemini 3 model is coming to the Gemini app and search, and developers will be able to access it immediately via the Gemini API, Vertex AI, AI Studio, and Antigravity. Google’s bigger gen AI model is also picking up steam, with both Gemini 3 Pro and its image component (Nano Banana Pro) expanding in search.

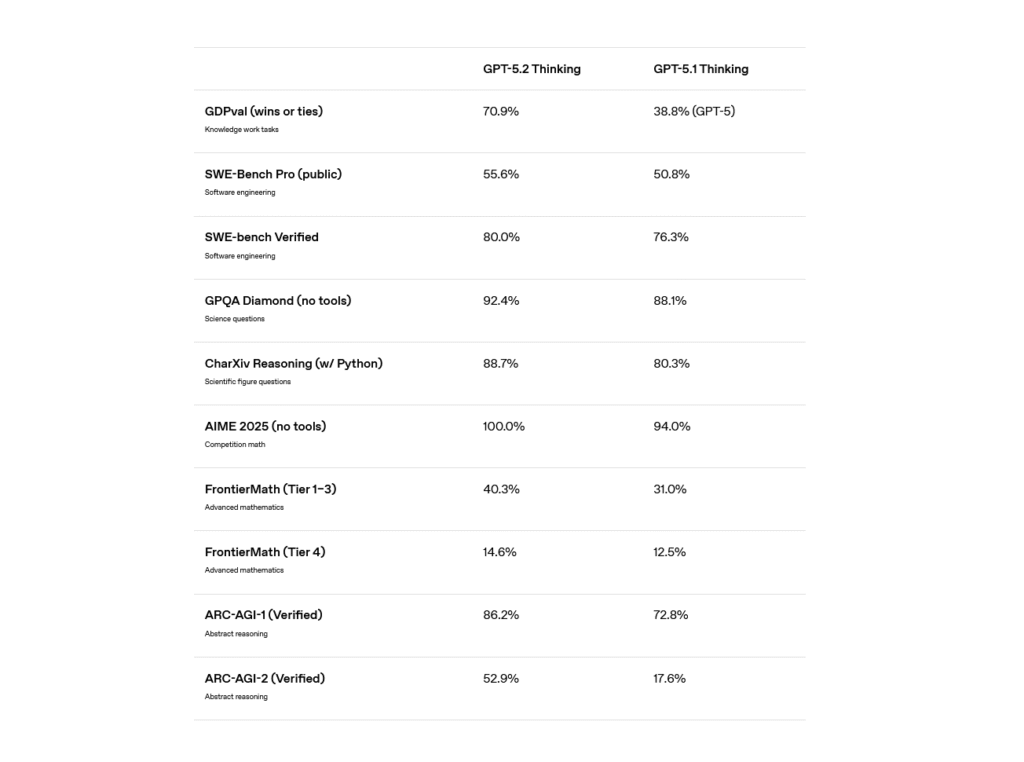

This may come as a shock, but Google says Gemini 3 Flash is faster and more capable than its previous base model. As usual, Google has a raft of benchmark numbers that show modest improvements for the new model. It bests the old 2.5 Flash in basic academic and reasoning tests like GPQA Diamond and MMMU Pro (where it even beats 3 Pro). It gets a larger boost in Humanity’s Last Exam (HLE), which tests advanced domain-specific knowledge. Gemini 3 Flash has tripled the old models’ score in HLE, landing at 33.7 percent without tool use. That’s just a few points behind the Gemini 3 Pro model.

Credit: Google

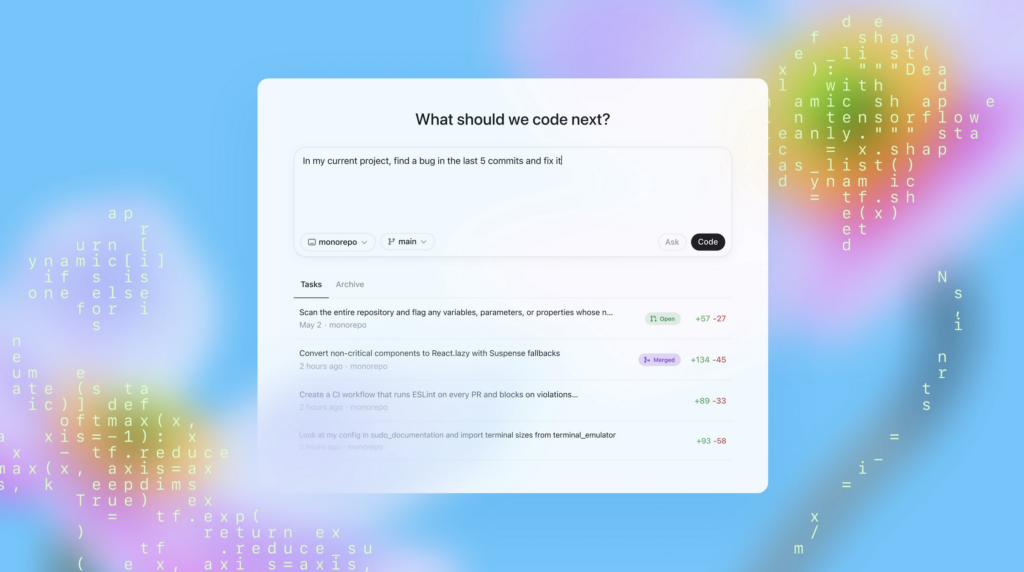

Google is talking up Gemini 3 Flash’s coding skills, and the provided benchmarks seem to back that talk up. Over the past year, Google has mostly pushed its Pro models as the best for generating code, but 3 Flash has done a lot of catching up. In the popular SWE-Bench Verified test, Gemini 3 Flash has gained almost 20 points on the 2.5 branch.

The new model is also a lot less likely to get general-knowledge questions wrong. In the Simple QA Verified test, Gemini 3 Flash scored 68.7 percent, which is only a little below Gemini 3 Pro. The last Flash model scored just 28.1 percent on that test. At least as far as the evaluation scores go, Gemini 3 Flash performs much closer to Google’s Pro model versus the older 2.5 family. At the same time, it’s considerably more efficient, according to Google.

One of Gemini 3 Pro’s defining advances was its ability to generate interactive simulations and multimodal content. Gemini 3 Flash reportedly retains that underlying capability. Gemini 3 Flash offers better performance than Gemini 2.5 Pro did, but it runs workloads three times faster. It’s also a lot cheaper than the Pro models if you’re paying per token. One million input tokens for 3 Flash will run devs $0.50, and a million output tokens will cost $3. However, that’s an increase compared to Gemini 2.5 Flash input and output at $0.30 and $2.50, respectively. The Pro model’s tokens are $2 (1M input) and $12 (1M output).

Google releases Gemini 3 Flash, promising improved intelligence and efficiency Read More »