It’s always a nice break to see what else is going on out there.

Study finds sleep in male full-time workers falls as income rises, with one cause being other leisure activities substituting for sleep. It makes sense that sleep doesn’t cost money while other things often do, but the marginal cost of much leisure is very low. I don’t buy this as the cause. Perhaps reverse causation, those who need or prefer less sleep earn more money?

The productivity statistics continue to be awful, contra Alex Tabarrok part of this recent -3.88% Q1 print is presumably imports anticipating tariffs driving down measured GDP and thus productivity. The more I wonder what’s wrong with the productivity statistics the more I think they’re just a terrible measure of productivity?

A model of America’s electoral system that primary voters don’t know much about candidate positions, they know even less than general election voters about this, so they mostly depend on endorsements, which are often acquired by adopting crazy positions on the relevant questions for each endorsement, resulting in extreme candidates that the primary voters wouldn’t even want if they understood.

It’s not really news, is it?

Paul Graham: A conversation that’s happened 100 times.

Me: What do I have to wear to this thing?

Jessica: You can wear anything you want.

Me: Can I wear ?

Jessica: Come on, you can’t wear that.

Jessica Livingston (for real): I wish people (who don’t know us) could appreciate the low bar that I have when it comes to your attire. (E.g. you wore shorts to a wedding once.)

Alex Thompson says “If you don’t tell the truth, off the record no longer applies,” proceeding to share an off-the-record unequivocal denial of a fact that was later confirmed.

I think anything short of 100% (minus epsilon) confidence that someone indeed intentionally flat out lied to your face in order to fool you in a way that actively hurt you should be insufficient to break default off-the-record. If things did get to that level? If all of that applies, and you need to do it to fix the problem, then okay I get it.

However, you are welcome to make whatever deals you like, so if your off-the-record is conditional on statements being true, or in good faith, or what not, that’s fine so long as your counterparties are aware of this.

Scott Alexander asserts ‘If It’s Worth Your Time To Lie, It’s Worth My Time To Correct It’ and I want to strongly claim that no, this is usually not true for outright lies and it definitely usually isn’t true for misleading presentations of facts that one could nitpick, and often doing so only falls into various traps, although it’s not clear Scott ultimately disagrees with that objection, he walks this back a bunch at the end. I do agree with his caveat that the actual important principle is that, if someone does decide to offer the correction, you don’t get to say they’re ‘supporting’ a side by doing so, or call them ‘cringe’ or describe it as ‘well acktually’ or anything like that.

What is the actual solution? Recalibration. As in, you pick up on the patterns, and adjust accordingly based on which sources pull such tricks and which ones are various amounts of careful not to do so. And yes, this does involve some amount of pointing it out.

Scott follows this up with the contrast of “But” versus “Yes, But.” As in, if [A] points out [B] while arguing for [X] was wrong about something that was load bearing to their argument, [B] needs to acknowledge they were wrong (the ‘yes’) before pivoting to other arguments for [X].

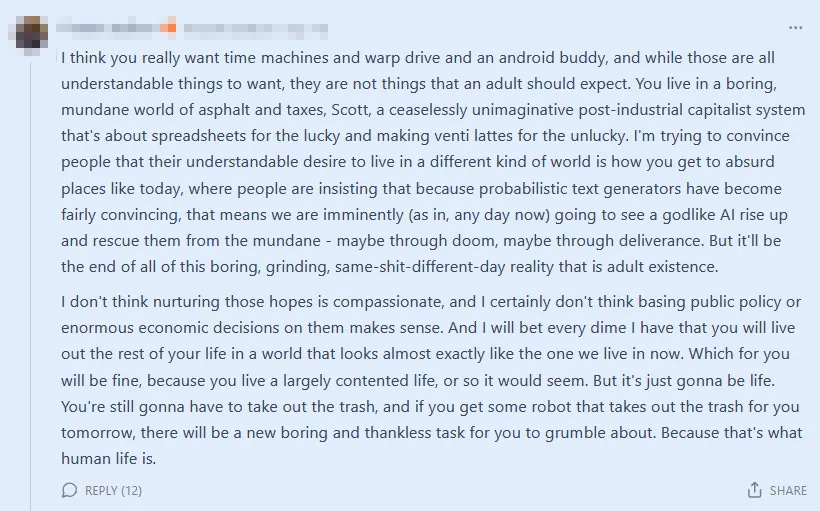

Scott Alexander: Someone wrote a blog post where they argued a certain calculation showed that the chance of a technological singularity in our lifetime was only 0.33%. I retraced the argument and found that if you did the math correctly, it was actually about 30%. Here’s the comment they left on that post:

I always find these ‘definitely the world will look almost exactly the same’ claims to be hilarious, given how that wouldn’t be true even without a singularity and hasn’t been true historically for a long time, but that’s beside the point here.

Cool thought, but I wish it had started with “Okay, you’re right and I’m wrong about the math, but I think you really want time machines and…”

I mean, not actually a cool thought either way. These thoughts are absurdly and utterly wrong. I for one want to say that while various sci-fi things would be nice, life right now (at least for me) is righteously awesome with only two real problems: Existential risk and other tail risks for highly capable future artificial intelligences, and our failure so far to cure human aging, because I hate getting old and I hate dying even more. That’s it.

But the ‘yes’ first would at least help, especially if you want continued engagement.

It is of course fine to say ‘I believe this because of [ABCD…Z], and any one of those would be sufficient, so even if you are right that [A] is false that doesn’t matter.’ But you have to actually say that, and also if I tear through [ABCD] in order you should be suspicious that this might correlate with the rest of your list.

I am doing my best to avoid commenting on politics. As usual my lack of comment on other fronts should not be taken to mean I lack strong opinions on them. Yet sometimes, things reach a point where I cannot fail to point them out.

If you are looking to avoid such things, I have split out this section, so you can skip it.

The Federal Reserve is cutting its workforce by 10% to be a ‘responsible steward of public resources.’ This is not a place I would be skimping on head count. There are so many ways for a marginally better Fed to make us a lot more money than it costs.

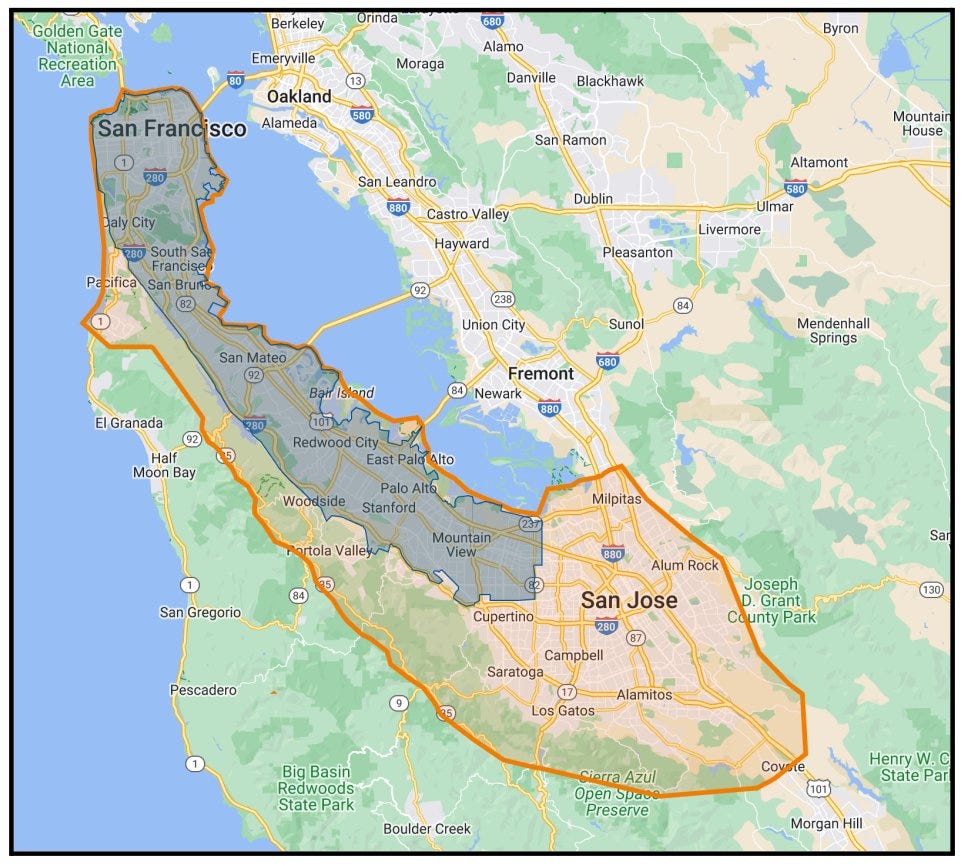

A fun question, who has the better business climate, California or North Carolina? It depends what kind of business. If you’re trying to build a car or open a sandwich shop, your job is way easier in North Carolina. But for some purposes, in particular tech, California’s refusal to enforce non-competes plausibly trumps everything else.

I knew the UK was arresting people for online posts, including private text messages, including ones that were very obviously harmless. I didn’t realize it was 1,000 people a month. The UK has a little over 40 million adults, so your risk every year is about 3bps (0.03%), over 1% chance that at some point this happens to you personally. That’s completely insane.

Field notes on Trump’s executive orders on nuclear power. It all seems neutral or better, but it’s not clear how much of it is new and actually meaningful. My guess is this on its own doesn’t do that much, and is less important than retaining or expanding subsidies.

Is US immigration still, for those who know the way, open for business?

Renaissance Philanthropy: U.S. companies can hire international talent in research and engineering in a matter of weeks, not months. But most never hear how.

New guide from @ImmCouncil breaks it down: OPT, O-1, J-1, H-1B cap-exempt and more. Whether you’re a Fortune 500 or a startup, odds are you’ll discover options you didn’t know existed.

“Trump’s shipbuilding agenda is sinking.” The Navy is described as 20 years behind in its goals. We need to face facts, we don’t have meaningful shipbuilding, and perhaps we want to pay massive amounts to change that while using proper tactics like export discipline, but the Jones Act and similar laws haven’t ‘protected’ American shipbuilding, they’ve destroyed it, and they need to go.

The point of a signature is usually not to prove that it was you who signed. Here’s a fun thread pointing out what’s really going on, that it’s mostly a tripwire that says ‘we are no longer Just Talking’ except in situations where you are for-real signing a for-real contract.

Strip Mall Guy: Signatures are a weird, outdated, and frankly laughable way to prove somebody approved a document.

Patrick McKenzie: (n.b. This is extremely well-known among companies which have a business process where you sign things. Most of them use a signature to demonstrate solemnization rather than authorization or authentication.)

As I’ve mentioned previously, solemnization is a sociolegal tripwire to say “There are many situations in society and in business where you’re Just Talking and up until this exact moment we have been Just Talking *and after this pointWe Were Not Just Talking. Do you get it?”

People who are unsophisticated about this think that the signature is somehow preventing someone from retroactively changing the terms of the contract. People who are unsophisticated say thinks like “Oh use digital signatures to PROVE that that has not happened. Sounds great.”

That is simply not the risk that the process is concerned with.

In some cases solemnization declines to being vestigial. For example, signing credit card receipts: no one cares.

Your bank does not expect a waiter to do forensic handwriting analysis on your signature versus the one on the reverse of your card, rejecting thieves.

If someone steals your card and perfectly reproduces your signature, and you say “My card was stolen; I did not pay for that dinner”, your bank will say “Yeah sounds really likely and we have no exposure here, OK restaurant eats it. Can we get you off phone quickly please?”

If same thing happens in a real estate situation, “Yeah that was not really me in the room signing that”, their lawyer is going to have some Pointed Questions and eventually your lawyer is going to have some Carefully Worded Professional Advice.

But a thing that a real estate closing is really really really concerned with is that all parties, who may be operating across a range of sophistications, understand that there was a long negotiation that got us to this point And That Negotiation Hereby Concludes Successfully.

(The number of conversations which begin “Well I didn’t really sell it to you” is greater than zero but it is less than it would be in a counterfactual world where there wasn’t the pomp and circumstance of a real estate closing.)

You can, by the way, get much [farther] than one would naively expect if one is willing to simply put forged documents in front of one’s lawyers and judges in an increasingly unrealistic fashion for many years. The immune system might not catch you for a very long time.

Many people tried it before Craig Wright did and many will try it after, and many of them felt very clever during all the years where they were still paying for their own housing. Did some get away with it? Yeah. There is no law of this universe that says justice inevitable.

Twitter introduces Polymarket as an official prediction market partner. Even the mid version is pretty cool, and executed properly this could be amazing, an absolute game changer. For now this only looks like Polymarket incorporating Twitter. I love that for Polymarket but the real value is the other way around. We need to incorporate Polymarket into Twitter, at minimum letting Tweets embed markets, and ideally complete community notes with markets attached, spin a market out of any tweet, trade right on Twitter, and so on.

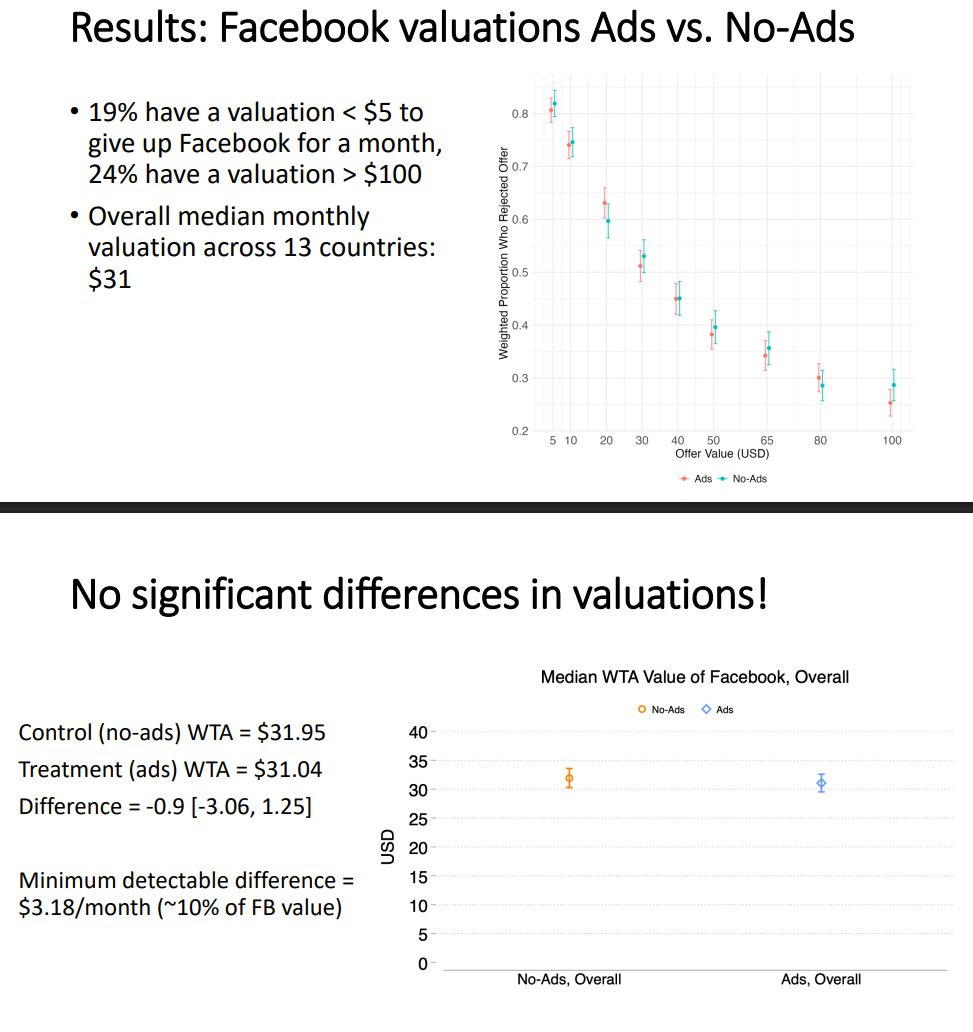

Removing political ads from Facebook and Instagram for six weeks before the 2020 American elections for a given user had no detectable effect on their political knowledge, polarization, election legitimacy, campaign contributions, candidate favorability or turnout. I basically buy it in this context. Very little changed in that six week period. It makes sense that in the end stages of a campaign, all the information flow here is already oversaturated. You’ve already seen the ads, and those ads are still flowing to everyone else you know and back to you, if you’re using Facebook and Instagram, and the rest of your world is also unchanged.

The most interesting aspect is that the most common type of ad was a fundraiser, they kept running them, and yet they didn’t have a noticeable impact on fundraising. This is strongly suggesting that the ads on the margin shift distribution, avenue or timing of contributions but don’t impact overall giving, at least once you get to this stage of the campaign. Alternatively, such fundraising had reached such over-the-top obnoxious levels that they were driving people away as much as they raised money. That could also explain there being no net impacts in other ways, that saturation especially of fundraising but also other ads served to piss voters off about as often as they helped.

Also I think this was a fantastic experiment and we should do More Like This, although perhaps Meta is not so excited to let them do it again for obvious reasons.

BlueSky appeals to creators over Twitter by not downranking links, drawing many of them into joining. It really is this simple, and it’s such Obvious Nonsense to think Elon Musk knows what he is doing trying to ‘keep people on the website.’

New Twitter bot plot twist, bots that reply to you then block the author, which gets the author deboosted, en masse, and the impact adds up. Neat trick, it’s new and the network of bots doing this is reported to be massive, in the thousands or more. Or perhaps the deboosting is incidental to the standard goal?

SHL0MS: sorry but this is incorrect. it is top of funnel for a WhatsApp group scam the deboosting may be a second order effect but that is not the purpose of the bots. they block the author to avoid being blocked and having their replies hidden.

This seems like a clear Skill Issue by Twitter. The algorithm should be able to figure this one out, also in this case they keep tagging the same account which gives the game away but there should already be strong statistical evidence that the activity isn’t real.

A special 0.5% of Facebook users were kept ad-free since 2013, and their ‘give-up-Facebook’ price is the same as ad-exposed users (~$32/month).

This suggests the ads are efficient, or even that more ads would be better, since they have marginal value to Facebook and the users don’t actually mind. Alternatively, it means people’s posts aren’t better than ads.

Tim Hwang: Statistically, there is some person out there who for completely random reasons has ended up on the better side of every A/B test and is unknowingly experiencing the most incredible internet you can imagine.

The thing about TikTok is indeed that it’s… not meant to be interesting? That’s actually a category error?

Noah Smith: TikTok is so insanely goddamn boring. Every time I watch a TikTok video, I think “man that’s meh”. Then I watch my friends consume it, and they’re just flipping past every video, even the ones they like. They don’t even finish 15-second videos. It’s pure channel-surfing.

Zac Hill: The best way to understand TikTok is by reading Wallace’s E Unibus Pluram. Wallace understood ~35 years ahead of his time how profoundly the phenomenon of attention capture would shape the way we construct society – and how our minds could be so easily instrumentalized.

If you have a Twitter variation with too sharp a cultural focus, it is extremely hard to break out of that focus and become a general solution.

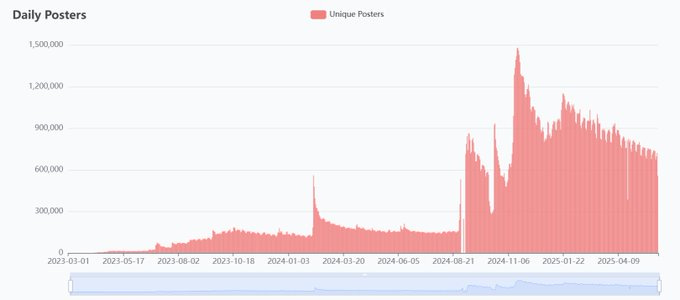

Paul Graham: Bluesky’s usage graph. The pattern here is bad. Spikes when a bunch of new people show up, followed by declines when the new arrivals are disappointed.

Andreas Kling: The problem with Bluesky (and Mastodon as well) is they mostly have one kind of asshole. They operate unchallenged, leading to extreme asshole saturation.

Meanwhile, X has *allkinds of assholes working against each other, so they kinda cancel each other out.

sin-ack: eh, more than anything it’s the consequences of disagreement. on ex dot com you get some pushback, at worst you mutually block and you’re done. on bsky you get added to a global block list and get hidden from half the people. on mastodon you and everyone on your instance get completely defederated and effectively permanently removed from the conversation. impartiality doesn’t exist because it’s “community operated”.

This usage pattern doesn’t have to doom you. It makes sense that you’d get traffic largely driven by major events and moments where new users show up who might not be a fit so many leave, and that without them you’d be static or in decline, and this is compatible with long term growth. Nothing wrong with losing small most days and winning big on occasion if the wins are big enough. In this case however it looks pretty doomed, as it’s hard to think of additional similar events.

A wonderful illustration of toxoplasma of rage as an active social media strategy. It’s great when people admit this is the plan.

If you’re dealing with Twitter bots, what’s the play?

This depends on what you care about. If you’re only thinking of your own experience, there is not that much to do beyond blocking the bot, short of getting block lists.

If you’re trying to promote the general welfare and fight on Team Humans, you can do more. Adam Cochran suggests first find the account the bot is shilling (if any), mute and then block it, to inflict maximum algorithmic pain. Then block the commentator. That sounds like more work than I’d be willing to do, but I notice that if I had one a quick way to tell an AI to do it, I’d be down.

The correlations here make sense, but a lot of potential explanations are not causal even before one examines the research methodologies involved:

Jared Benge and Michael Scullin (via MR): The first generation who engaged with digital technologies has reached the age where risks of dementia emerge. Has technological exposure helped or harmed cognition in digital pioneers?

…Use of digital technologies was associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairment (OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.35–0.52) and reduced time-dependent rates of cognitive decline (HR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.66–0.84). Effects remained significant when accounting for demographic, socioeconomic, health and cognitive reserve proxies.

Tyler Cowen: So maybe digital tech is not so bad for us after all? You do not have to believe the postulated relatively large effects, as the more likely conclusion is simply that, as in so many cases, treatment effect in the social sciences are small. That is from a recent paper by Jared F. Benge and Michael K. Scullin. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

It’s definitely great if the early versions of digital tech are associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline, although I would not presume this result carries over to long term exposure to modern smartphones and the associated typical use cases. And even if it does still apply, this is one of many aspects of digital technology, and it very much does not allow us to ‘think on the margin’ about this, as the most likely causal explanations involve enabling people to meet minimal thresholds of cognitive activity that serve to slow down cognitive decline.

As per this righteous rant thread from Conrad Bastable, it is very true that when you buy a new computer, by default it will come pre-loaded with a lot of crap, and Windows 11 will waste a bunch of resources, and that Macs come with a lot of objectively terrible software, and that it takes a remarkable amount of deliberate effort to fix all this even if you mostly know what you are doing, during which you are subjected to ads.

Conrad Bastable: Your [Mac] Start menu comes preloaded with Politics and Baseball media content. Nightmares beyond comprehension.

Framework: The strongest argument in favor of 2025 being the year of the Linux desktop. To the other operating systems, you are the product, not the customer.

This isn’t a big deal for a knowledgeable user. No, the startup button in Windows spiking the CPU isn’t a practical problem, and it is a one-time not that high cost to get a lot of the stupid bloat out of the system, and letting apps send you notifications is good, actually, given there’s an easy way to turn it off for each app the moment they try to abuse it. I have made peace with the setup process.

What I don’t fully understand is why all of this is true. It’s one of those ‘yes I get it but also I don’t, actually.’ It seems like an obviously easy selling point to say ‘this PC doesn’t come with any ads’ and similar. People would definitely pay a bit more for that. You’d get customer loyalty and word of mouth, as your product would perform better. An expensive purchase is exactly a place where you shouldn’t need to do ads. And yet, yes, they consistently do this anyway, even when it is obviously net destructive to long term profits. Why is my smart TV so terrible, even if it’s ultimately fine and way better than an old dumb one? Yes, I tried using an XBox or Playstation instead, ultimately I found it not better enough to bother.

But even if you hate all that, what are people going to do, use Linux? Seriously?

Mustafa Hanif: No operating is serious if it doesn’t support:

Adobe Photoshop, Microsoft Excel, Capcut, StarCraft 2, Fortnite, Valorant

Framework: The most important of those six works on Linux.

I mean, okay, one out of six with the right link, I bet it’s more if you knew where to look, and you’re going to suggest this to people who can’t debloat their Windows box? Every now and then someone pitches me on switching to Linux, and every time it seems like an endless nightmare to get up to speed and deal with compatibility and adoption issues, even if I didn’t care about games.

Ah, the circle of online life:

Aella: i started out on X determined not to block anyone. then i entered 2nd stage: blocking everyone who seemed even a little unkind. but now im progressing to 3rd stage: giving up on blocking ppl cause they’re too petty to warrant the effort of moving finger to block button.

As your account grows in reach, the value of blocking any one account that is interacting with you goes down, so you bother doing it less, and eventually have to rely on mass blocks, block lists and automated tools. That makes sense. I’m still in full block people mode, although ‘a little unkind’ is not enough to trigger it for me. It used to mostly be mute but it’s now block since that doesn’t stop you from seeing my posts either way.

Steve Hsu reports lots of optimism for both artifical wombs and gene editing of embryos, and that a meeting at Lighthaven convinced him they’re coming sooner than you would think. I don’t have the optimism he has about this as a hedge against existential risk given the timelines involved, but there is wide uncertainty about that, it’s very much a ‘free’ action in that regard, it’s all upside.

A reasonable perspective on both Rationality and also The Culture, except that with this perspective redemption is possible only through grace, and that kind of thinking has a long history of really messing people up if they don’t feel the grace enough:

EigenGender: I think that interacting with rationality community online before I interacted with them in person gave me the community wide equivalent of when someone puts their partner up on a pedestal at the start of the relationship and it ruins the relationship forever.

It is by any objective standard a great community but it broadcasts an even more beautiful sirens call into the Internet and then fails to live up to the standards it sets for itself. It’s also failed to fix all my life problems for some reason.

Rationality is like The Culture. It is the best thing that ever existed and also bears an incredible and irredeemable moral sin for not doing more with the opportunity that’s been handed to it.

[the above tweet is exaggerated for comedic respect wrt. Rationality but sincerely captures my feelings towards the culture]

There definitely is an important pattern that bright abstract thinkers do many things, including Effective Altruism, that seem often motivated by striving to be and think of oneself as Good rather than Bad, with more discussion at the thread. We have a culture telling people (especially men but also everyone) that they and key parts of themselves and our entire civilization (and often even humans period) are Bad – we de facto now have the Christian idea of original sin without the Christian standard path to redemption, oh no. The historically prototypical ‘good deeds’ and ways to make yourself Good are, to bright abstract thinkers, either obviously fake or transparently inefficient and silly, or at least not sufficient to do the trick.

Checkmate.

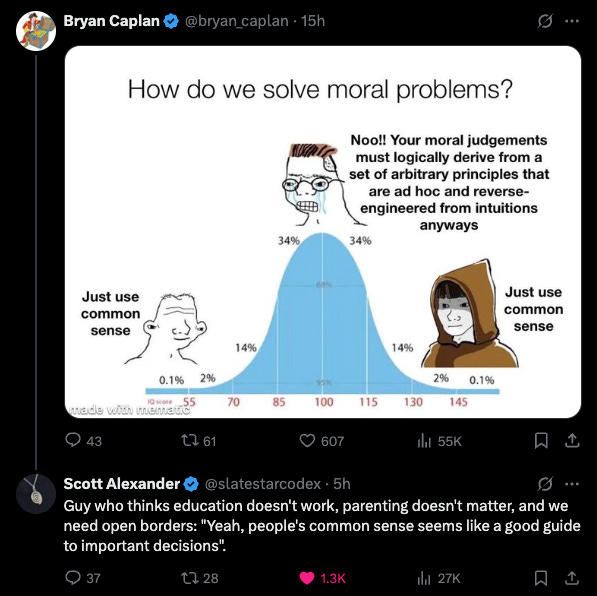

You shouldn’t not use common sense, but the word ‘just’ is not okay here.

There was a recent exchange of posts between Tyler Cowen and Scott Alexander about USAID. I wrote an extended analysis of that exchange and learned by doing so, but am invoking Virtue of Silence and not posting it. I will simply note that everyone involved agrees that it is completely false to say that anything remotely like only 12% of USAID money ultimately went to helping recipients, and that anyone using that claim in a debate (such as Marco Rubio or JD Vance) is doing a no-good very bad thing.

Last year Florida banned lab-grown meat, and I went through three rounds of trying to explain why, even though I wouldn’t ban it, a reasonable person who wanted to continue eating regular meat might want such a ban, given how many people are itching to ban or ostracize or otherwise destroy all other meat consumption.

I am the first to admit I am not always perfect about adhering to the principle of ‘if you care about an issue you need to understand where all sides and especially the opposition are coming from’ but I do try and I think it is important to do so.

I am quoting people on this again because there was another round of this argument recently, and because it is a microcosm of a lot of other things going on in politics, even more so than when this came up last year, culminating in Matt Yglesias presenting this as a fully one sided issue and saying ‘Banning Lab Grown Meat Is Stupid.’

Its Not Real: RWers in red states are banning lab grown meat because it will be used as a a cudgel against them in the future. There is no faith that lab grown meat will be on an even playing field in the market. It will be used for Dekulakization if the opportunity presents itself.

They saw what happened or has been attempted against mineral extraction industries. This is secondary to economic efficiency, market viability, meat taste quality, or meat nutritional quality. Its tertiary to the replication crisis and being able to trust this new meat.

Its the perfect anti-Chud machine, “Look at our superior product. Higher quality in tastes and nutrients, environmentally friendly, and morally superior since no animals died.” Its a short jump from there to heaping new regulations on farmers to strangle them financially.

(Thread continues as you would expect.)

PoliMath: This is a really good thread of why people are disinclined to permit lab-grown meat It feels like a back door to banning real meat and people are really sick of being tricked and forced into accepting shitty things they don’t want.

Derek Thompson: It’s a typical conservative opinion—I’m afraid that the emergence of new things will mean I won’t be able to enjoy my old things—and you’re free to have it, but I’m surprised somebody who’s worked in tech doesn’t see the limitations of this argument in his own field.

“If we allow this new thing to develop, the state will eventually ban this old thing I like, so we have to smother the infant tech in the crib” is a very very anti-progress position to take, in any field. You’re basically endorsing incumbent bias as a first principle because of a make-believe fear that Democrats are on the verge of banning steak.

PoliMath: Let’s talk about this. “Show me the legislation” is a head-fake. We aren’t in the legislation phase of this project. But every lab meat company markets itself as the future of meat and calls for an end to natural meat. Every single one.

Biocraft: “Farmed animals live shorter and more brutal lives today than ever before. In the USA, 25 million of them are killed every single day. We say enough is enough”

Enough is enough, huh? Oh that’s probably just harmless rhetoric.

SciFi Foods: “The future is coming soon.” “We’ll all be able to enjoy our burgers without destroying the planet.”

Huh. And what will happen to those planet-destroying farms? Probably nothing, I guess.

Fork and Good: “a vision of scalable, sustainable, human and cost-effective future for meat” “change meat production forever”

Forever, huh? Not just bringing more options to the consumer, you want to change meat production forever?

Oh, that’s probably just marketing.

…

that is what is so annoying to me about this. I’m not so much advocating a ban as saying “Can you understand why this bothers people?” and too many of the answers are “no, if this bothers you, you’re a dummy who is imagining things”

No they aren’t. They’re being told things.

Kat Rosenfeld: this thread is garnering a lot of argumentative replies to the effect of “well people shouldn’t feel that way”, making it a fascinating microcosm for the brokenness of political discourse overall.

“well people shouldn’t feel that way” okay cool, but they do, and will continue to until or unless you can affirmatively address their concerns.

Mike Solana: I am against the lab meat bans, and enthusiastic about experimentation here, but decimating global meat consumption is the explicit goal of many people excited about the space, and pretending that isn’t true is just dishonest

I think the conversation you probably want to be having is “factory farming is morally bad and unhealthy and we need an alternative,” but proponents haven’t had much luck with that argument, and especially not abroad, so here we are

Last thought, the average normie “muh steak” guy (me some days) isn’t stupid. He knows you’re being dishonest. And this breeds further distrust / animosity for the tech, and tech generally. For ppl who never learned from COVID: if you can’t be honest, please just say nothing.

Derek Thompson: I’m describing reality — you’re banning meat, Dems aren’t — and you’re describing a psychology: “We’re afraid and want protection.”

Fine! I get that. But I’m surprised to see you so clearly make the argument that you’d rather feel safe than be right.

Emma Camp: “We need to ban this thing to prevent other people from hypothetically, sometime in the far future, making it mandatory” is not a compelling argument.

Josh Zerkle: let’s talk this out over a pack of incandescent light bulbs.

It’s also worth noting that a number of the largest multinational meat packers are acquiring or investing in lab meat start-ups, to hedge their bets.

Again, I don’t want to ban lab grown meat, because I am willing to stick to my guns that you don’t go around banning things, even if you don’t like where all of this is going. But I understand, including for those who don’t have any financial skin in the game. I disagree, but it isn’t dumb.

If you don’t understand why, think about it until you do.

It is flat out gaslighting to call this, as Derek Thompson does, ‘a make-believe fear’ or ‘psychological issue’ rather than a very real concern, or to deny that this is the stated intention of the entire lab grown meat industry and a large number of others as well, and it is gaslighting to deny the clear pattern of similar other bans and requirements that have made people’s lived experiences directly worse – whether or not you think those other bans and requirements were justified.

There is less than zero credibility for the claim that no one will be coming for your meat down the line, no one is even pretending that they’re not coming for it, at best they are pretending to pretend.

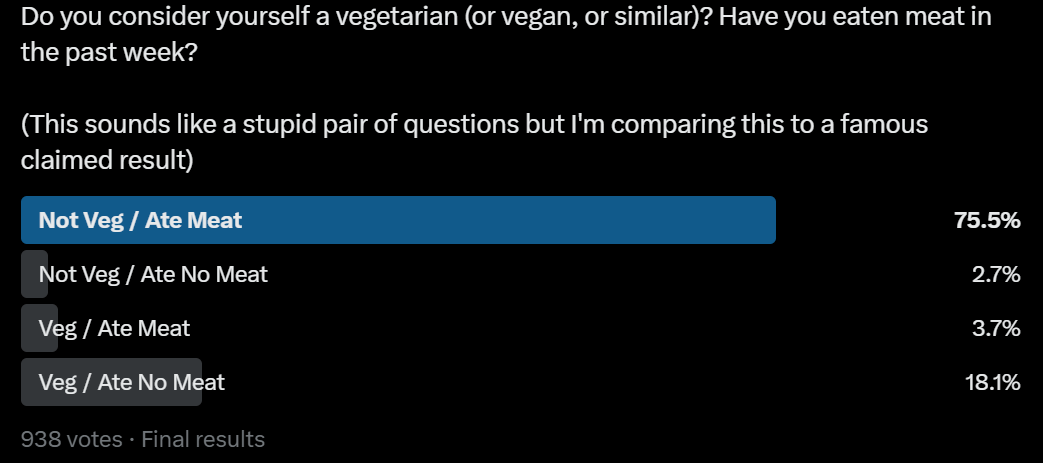

A claim I have heard is that 50% or more of self-identified ‘vegetarians’ ate meat in the past week. When you ask my followers both questions at once, they don’t agree and it is only 17%. But obviously asking both at once and asking my Twitter followers are both going to lower the percentage here.

Also 22% of respondents were vegetarian or vegan.

Arc was (as of May 22) hiring a Chief Scientific Officer. Seems like a great opportunity.

Ryan Peterson asks what is the best history book you’ve read?

Paul Graham: Medieval Technology and Social Change

The Copernican Revolution

Life in the English Country House

Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy

Anabasis

The Quest for El Cid

The World We Have Lost

Lots of other people replied as well, seems overall like great picks but there are so many so I haven’t rad most of them. If I had to pick one, I’d pick Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

Cate Hall warns against the ‘my emotions really mean it’ approach to commitment, because it doesn’t work. Your emotions will change. What you have to do is engineer things, especially using forcing functions, such that success is easier than failure. For her the most prominent of these was diving into her relationship and marrying quickly. The whole system requires real accountability and real consequences. It has to actually hurt if you don’t do it, but not hurt so much you’ll back out entirely. You also need to watch out before doing too much to cementing a life or lifestyle you don’t want.

Connor: I don’t think I’ve said this before, but I think this post might have changed my life? Everything about it. The feel vs make, the forcing function, the aspiration of who you want to become. As soon as I wanted a counter point, she made it and deconstructed it. I will make changes in my life due to this post. I say that maybe 1-2 times a year (funny enough they are always blog posts/essays found via Twitter). What simple but great writing. Full post in her 2nd tweet.

The method Cate Hall describes here is highly useful, but far from the only component, and by its very nature this strategy involves real risk of costs big enough to hurt and without corresponding upside. As Cate would no doubt agree, a bet (where you can win or lose) is better expected value than a Beeminder (where there is only downside, except for the motivation).

Ideally you want other commitment mechanisms that involve upside. My central move is, quite literally, to realize that when one commits one is betting not only one’s external reputation but also one’s inner reputation, one’s thinking of oneself as someone who keeps similar commitments and thus the power of similar commitments to bind your actions.

Being able to use commitments effectively is super valuable, so endangering that by breaking commitments is a big cost, which enforces the commitment on its own. And every time you hold strong, the power grows. And this dynamic forces you to calibrate, and only use commitments when you mean them.

If your children are set to inherent vast amounts of wealth, there are three schools of thought on how to handle this:

-

Never leave anyone you love more than [X million] dollars, make them earn it, either for their own good or to donate the rest to worthy causes.

-

Make them earn it now, then let them inherent it later, or do so if they earn it.

-

Give them a trust fund now, so their life is better and they acclimate to wealth.

I am with Sebastian and Mason that plan #2, forcing your kid to live like a ‘normal person’ and obsess over small amounts of money so they can be like everyone else or learn to ‘value the dollar’ or what not, is actually terrible training for being wealthy, for the same reason lottery winners mostly blow their winnings. Choose #1 or #3.

You do want them to ‘earn it’ and more importantly learn how to operate in the world, it’s totally fine to attach some fixed conditions to the unlock of parts of the trust fund, but you don’t do that by giving them Normal People Money Problems.

Sebastian Ballister: people are dunking on this [now deleted tweet], but I went to college with a bunch of people whose parents are running business worth 9-figures who have left their kids to their own devices to find jobs in tech or finance.

Their kids will all be in completely over their heads when they do inherit.

Mason: I actually agree here

If you’re going to pass on extreme wealth, “trust fund kid” is actually the way to go. Properly managed, it’s not an endless bank account, it’s an asset portfolio with training wheels

If you want your kids to be “normal” then fine, don’t leave them a mountain of wealth

If you’re leaving them a mountain of wealth, help them learn how to treat it like a custodian of multigenerational resources rather than a lottery they win when dad dies.

I do think this is different from putting them in charge of your own business straight away. It makes sense to make them train via other work, but that doesn’t mean you want to squeeze them for money while they do that. You want to design an actual curriculum that makes sense and gets them the right experience, in the real world.

I see a big difference between ‘you have to hold down a real job’ versus ‘you have to focus on personal cash flow.’

Danger Casey: I have a good friend who’s family has serious generational wealth through a business his father started

Despite following the same degree path, his father told him to work elsewhere for 10 years then hired him as a director. Then made him work 10 years up to president before handing the business over

It gave him experience and perspective elsewhere, gave him time in the business to learn *andprove himself to existing staff, and now he’s running the show

Frankly, I think it was brilliant.

Emre: Elite business schools are full of these kids who worked a few years as normies, then go to elite MBA, before settling into family business.

It’s a good path, and probably better than being a 21 year old heir inside the business.

Wedding costs seem completely nuts to me. Also, buffet is better? But I love that the objection here to that people have to get up, not to the RSVP-ordering rule.

Allie (as seen last month): I’m not usually the type to get jealous over other people’s weddings

But I saw a girl on reels say she incentivized people to RSVP by making the order in which people RSVP their order to get up and get dinner and I am being driven to insanity by how genius that is

Allyson Taft: I saw that, too. It’s kind of gross, though, because who wants a wedding where people have to get up to get food?

Ourania: Literally just discussed this with husband. Imagine the cost difference of $20 per person vs $50 per person and your list is over 100 people!

Rota: “Having your guests get up to get their food is extremely rude” good lord help me.

Teen Boy Mom: I paid for my own wedding and we did a free seat buffet at a high end French restaurant. They still got filet, and they could sit wherever they wanted and it cost me less.

In general, yes, a good restaurant is better than a buffet. But a buffet will be better than most catering that you’ll get at a wedding or other similar venue.

The deal on the catering is universally awful compared to what you get, even without considering that many people do not want it, and often quality is extremely bad. And by going buffet you get the advantages of a buffet, everyone gets what they actually want, or at least don’t mind. So yes, this means you have to get up to get your food, but so totally worth it, and I don’t even see that as a disadvantage. You can use an excuse to flee the table sometimes.

A series of branching exchanges on the ways to draw distinctions between interactions that are ‘transactional’ versus ‘social.’

Flowrmeadow: I’m sorry but if you want to stay at my apartment for your NYC trip you need to buy me dinner or at least a $20 bottle of wine. Just something that shows you give a shit man. It’s surprising how no one does this

Alanna: it is so insane to me that people no longer understand the difference between ‘transactional’ and ‘social graces.’ Like, if a friend saves you hundreds in lodging fees, buy them dinner and wine. That’s basic etiquette.

And, if you cannot afford anything lavish and are staying out of desperation… just be honest: “thank you for taking me in when I’m in such a tough spot, I can’t wait to make it up to you.” And people will be understanding. Why are people becoming so bad at social conventions???

Aella: That’s a transaction! If you’re giving a gift but you’ll be hurt if they don’t give you something back, then it’s not a gift freely given!

I once gave a friend a very large financial gift and I only did it after I fully came to emotional terms with them doing absolutely nothing.

Ta-Nehisi Quotes: In ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel,’ there’s a great scene where the protagonist is gifted expensive cologne by a colleague. Although impoverished, he makes a show of offering his friend a quarter in return. The friend magnanimously declines. The thought is what is important.

Rob Bensinger: I think all three of these are good things: “giving something without expecting anything in return”, “giving something while expecting a specific thing in return”, and “giving something with the expectation of this vaguely influencing a social ledger of back-and-forth favors”.

It’s good to keep these three things distinct, IMO, and it’s good to be clear about whether “non-transactional” is referring to “truly expecting nothing in return” option vs. the “vaguely influence the social ledger” option.

I would go a step beyond Rob here, there are a lot of related but distinct modes here, and asking for symbolic compensation does not make something transactional, even if that symbol costs some money. The point of buying dinner is not that it’s a fair price, it’s that it shows your appreciation. Indeed, this can serve to avoid having to write an entry, or a much larger entry, into that social ledger.

Then there’s the question of smaller things like dinner parties.

Alyssa Krejmas: So I host a lot of dinner parties. In SF, 85% of guests show up empty-handed. And if someone does bring something like wine & it’s not opened, they’ll often take it back home. I’ve seen this happen not just at my own parties, but others’ too. It’s so odd to me. That was never the etiquette in New England—and I really don’t think this should be a regional thing?

Zac Hill: This is the single thing that bothers my wife (Venezuelan) the most about many of my friends. She is like, this is categorically exclusion-worthy behavior. Like for her it is fart-in-an-elevator-tier anathema.

PoliMath: People in the US need to understand that our country is functionally more than a dozen different countries, each with their own cultures and patterns.

If something is common in New England and you aren’t in New England, take the role of cultural ambassador & inform your guests.

I consider it fine to show up empty handed, but better to ask if you can bring anything. We have one friend who explicitly bars anyone from bringing anything, because he wants to curate the whole experience. I think that’s great.

My family try to host Shabbat dinners on Friday evenings for friends (if I know you and you’d like to come some time, hit me up), and we explicitly say that we don’t expect you to bring anything, although you are welcome to do so, especially dessert, or wine if you want to be drinking but our crowd usually doesn’t drink. It is nice when people do this. But also I think at this level, a thank you works fine.

Ah, the joys of someone with authority demanding documentation to prove that you do not need documentation. And the dilemma of what to do in response, do you produce it (if you have it) or do you become the joker? Here the example is, woman who is 24 weeks pregnant being told to prove she isn’t 28 weeks pregnant, because if she was she would need a doctor’s note to fly.

A fun proposal is to reduce sweets consumption by having sweet food with probability 2/3rds, determined by random draw. My problem with this proposal is that, when something isn’t always available, it makes you much more likely to take that opportunity when it is available, you don’t want to miss out on your opportunity. Thus, you need a variant: If you get a yes, you keep that yes until you use it, so you get rewarded rather than punished if you skip your chance.

Benjamin Hoffman offers a model of the kind of personas, performances and deceptions we expect from politicians and the managerial class.

Atlanicesque: We have a system which selects for dishonesty, but in a peculiar way. We select for “sincere deceivers,” people who lie and otherwise act dishonestly for personal gain, yet are intellectually capable of rationalizing their behavior to themselves so completely they feel no shame.

Such people are uniformly horrible to deal with in any extended or involved fashion, so of course our society has decided to put them in charge of everything important.

Benjamin Hoffman: I think I disagree on some important details with that tweet; the people in leadership more typically have a mindset that normalizes types of opportunistic identity-performance, and invalidates the very idea that such performances could be held to the standard of honesty.

…

A simple example is Kamala Harris’s famous “it was a debate,” which openly implied that criticisms articulated in debate against a then political opponent aren’t supposed to add up with what you say after you’ve teamed up with them and thinking otherwise is for naive suckers.

This is not really “rationalized,” since there’s no reason offered; it’s merely a description. If asked for a justification in a context where they feel compelled to offer one, people who act like this might say “it’s the way of the world” or “you have to be realistic.”

Less famous people in the professional-managerial class have to navigate an analogous custom in their employment situations by constructing a persona that claims to care about the job authentically and not transactionally.

This doesn’t exactly entail an active 24/7 performance of the professional persona the way Robert Jackall’s book Moral Mazes claims, but it does tend to involve consistent readiness to engage that facade, and inhibition of anything that would challenge it too much.

I don’t think this is fully cross-culturally invariant. My impression is that the Russians have something more internally honest going on, though obviously something else is very wrong with Russian culture, and I predominantly speak with emigrants, who are therefore exceptional.

E.g. I met a Russian-American woman who spoke casually in a private social setting about valuing leisure and not wanting to work more than necessary, but when asked what she did for work, frictionlessly code-switched to corporate-speak.

I think those people mostly don’t even see it as deception or lying anymore. It’s simply the move you make in that situation. And I can actually model that perspective pretty well, because it’s exactly how I feel when I’m playing poker or Diplomacy.

I see Jackall as describing the attractor, and ‘how high you bid’ in moving towards that attractor, which is mostly about signaling how high you will continue to bid later, is a large determinant of ‘success’ within context. Willingness to engage a facade is sufficient to do okay, but you’ll probably lose to those who never drop the facade, and especially those who become the mask.

There is now sometimes a huge discount for buying airline tickets in bulk? In one extreme example it was only $1 more to buy two tickets rather than one. This is happening on American, United and Delta, so far confined to a few one way flights.

The growing Chinese trend of paying a fake office so you can pretend to work. Isn’t this at its base level just renting coworking space? The prices seem highly reasonable. For 30-50 yuan ($4-$7) a day, or 400 yean you get a desk, Wi-Fi, coffee and lunch. For more money you can get fake reviews, or fake employees, or fake tasks, and so on. Fun.

The base reported use case is to do this while looking for work, but also you could use it to, you know, actually work? There’s nothing actually stopping you, you have Wi-Fi.

This month I learned the Air Force had an extensive ritual where they told high ranking officers they were secretly reverse engineering alien aircraft purely as a way to mess with their heads, and this likely had a role in the whole UFO mythology thing. Of course, some who have bought in will respond like this:

Eric Weinstein: The title of this @joerogan clip from #1945 is literally: “We might be faking a UFO situation.”

OBVIOUSLY.

As I have said before, “When we do something secret and cool, we generally pair it with something fake.” This is standard operating proceedure (e.g. Operation Overlord was D-Day/Operation Fortitude was a Faked Norway Invasion). This is what ‘Covert’ means. Covert means ‘Deniable’. Not secret, but *deniable*.

You see, the evidence that this was faked only shows how deep the conspiracy goes.

It’s tricky to get this right and avoid anyone being misled, because you’re combining a number of related strategies and concepts into the group that is contrasted with, essentially, ‘cheap talk,’ and this risks conflating multiple concepts. But I think ‘costly signal’ is still our best option here most but not all of the time, as a baseline term, because simplicity matters a lot.

Richard Ngo: “Costly signaling” is one of the most important concepts but has one of the worst names.

The best signals are expensive for others – but conditional on that, the cheaper they are for you the better!

We should rename them “costly-to-fake signals”.

Consider an antelope stotting while being chased by lions. This is extremely costly for unhealthy antelopes, because it makes them much more likely to be eaten. But the fastest antelopes might be so confident the lion will never catch them that it’s approximately free for them.

Or consider dating. If you have few options, playing hard to get is very costly: if your date loses interest you’ll be alone.

But if you have many romantic prospects it’s not a big deal if one loses interest.

So playing hard to get is a costly-to-fake (but not costly) signal!

I think “costly” originally meant “in terms of resources” not “in terms of utility”. So a billionaire spending 10k on a date is a monetarily-costly signal which shows that they have lower marginal utility of money than a poor person.

But cost in terms of utility is what actually matters in the general case, and so “costly (in resources)” signaling is just a special case of “costly (in utility) to fake” signaling.

I get why one would think that ‘costly in utility to fake’ is the core concept that matters, but a bunch of other differences seem important too.

-

Is the signal costly or destructive even if it is accurate? If it is costly, is this a fixed cost (pay the cost once in order to signal, get to signal cheaply thereafter) or is it marginal (pay the cost each time you want to send the signal)?

-

Is the signal effective because it means it was cheap to send (either on the margin or in general)? Or is the signal effective because it was expensive to send, and you are sending it anyway, thus proving you care in some sense?

-

Does the signal involve destroying a bunch of value? Or does it involve transferring value or generating it for others (or even for yourself)?

-

Is this a positional signal? Or is it an absolute signal?

This matters because the goal is to have signals that maximize bang-for-the-buck in all these senses. I worry that calling it ‘costly-to-fake’ while accurate would (in addition to being longer) centrally point people towards asking the wrong follow-up questions.

“Travel” doesn’t have to be fake. Tyler Cowen travels. Eigenrobot goes a little too far here, on many fronts. But most of us at best Travel™, which can involve seeing some cool sights but mostly is something one does to have done it, except when we are meeting up with particular people or attending an event, which is a valid third thing.

Eigenrobot: “travel” is fake

no one except lord myles has “adventures” when they travel

you are staying at a hotel, paying large sums of money to have a far worse experience than you could have in your own home and a far softer experience than you could have by spending a weekend in jail

“i love to Travel” why have you failed to establish your home as a place of serenity and joy, to the extent that you feel psychically uncomfortable there and strive to get away from your life whenever you can, viewing it as the highest good?

you are not well

“i Travel” you can go wherever you like in the world but you will never escape yourself

“i want to spend time with people different than myself!” no you dont. there are Different people in your city.

go hang out with the homeless or some seniors hmmmm? i guarantee these people are more different from you than are your age and class peers in europe

the only really good reason to travel recreationally is to see old friends and travel in this case is, in a real sense, like coming home after a long time spent away.

Paul Graham: I was going to explain why you’re mistaken, but then I realized that the places I like to visit would be less crowded if people believed this, and moreover the people who’d stay home would be exactly the ones I’d want to.

The Galts: Ah but I do so on a small boat. I have adventures when I travel … and never need to pack a suitcase.

Eigenrobot: Yeah that’s legit.

Again, are some real advantages to Travel™, especially if your home base is in a place without all the things, you shouldn’t quite do zero of it. But most Travel™ is, I think, is either a skill issue due to an inability to relax without it, or a parasocial or future memory and anticipation play.

Plus you have to plan it. Some people enjoy this, and they are space aliens.

Daniel Brottman: having to decide things in advance is crazy lol. “yeah i’m gonna want to get on a plane on the 22nd of august.” statements dreamed up by the utterly deranged. they have played us for absolute fools.

QC: had to think recently about whether i wanted to sign a yearlong lease in august – bro i do not know a single thing about what the world will look like by august of NEXT year.

Daniel Brottman: holy shit is august of 2026 even real, i heard it was just a myth.

Lighthaven now has a podcast studio. I had the chance to tape in there with Patrick McKenzie, it is a quite nice podcast studio.

The IRS tax filing software that everyone except TurboTax loves, and that they got the Trump administration to attempt to kill, has instead gone open source, with its creators leaving government to continue working on it. Something tells me plenty of people will be happy to fund this. So maybe this was a win after all. I am sad that my taxes involve too many quirky details to use anything like this.

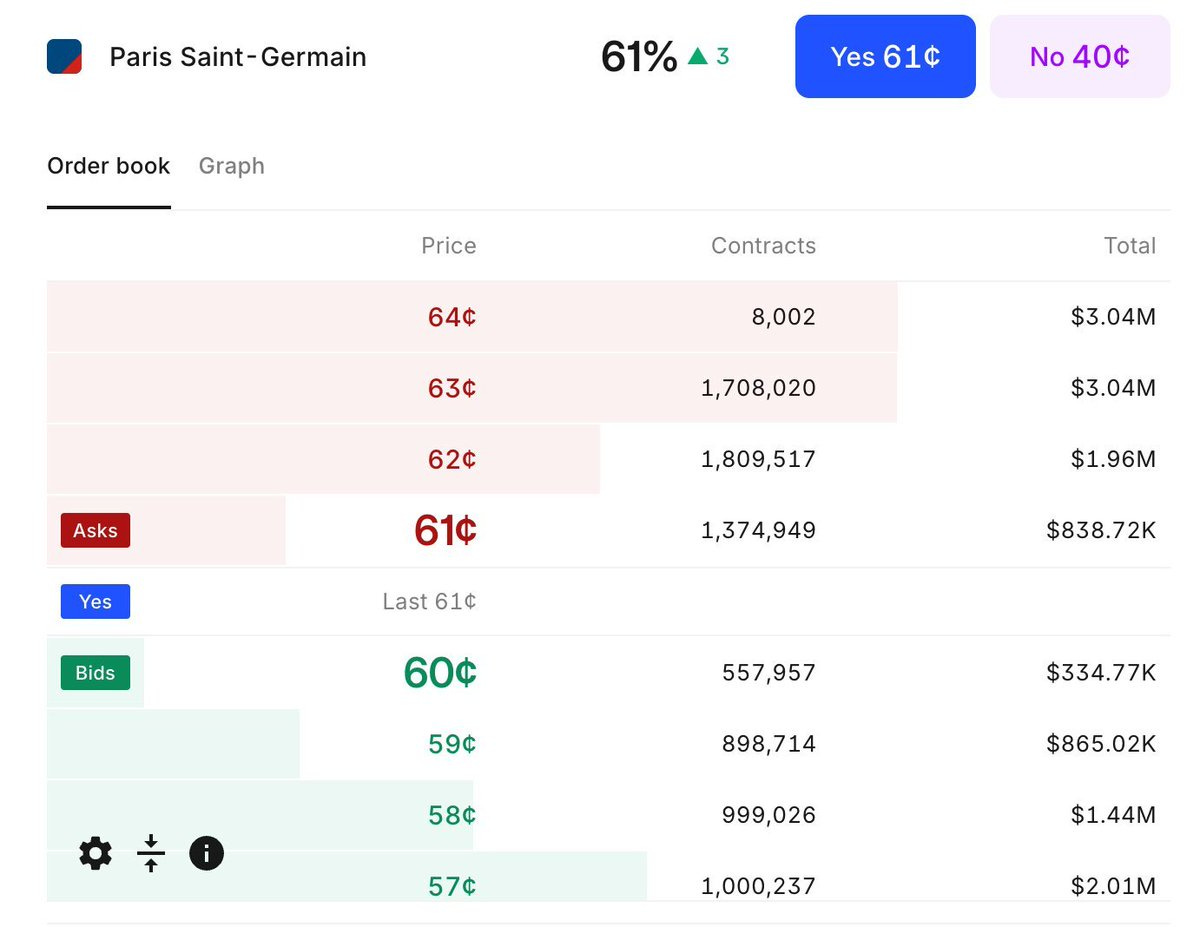

Kalshi sports betting is by all reports going well.

This is very much The Big Game, so these numbers are not as impressive as they look. But it’s still respectable, and most importantly the pricing is good and it is fully legal. I consider products like DraftKings and FanDuel effectively abominations at this point, but if you don’t want to use overseas books this seems fine:

Here’s another ‘why America’s implementation of sports betting is terrible’ essay. We not only allow but essentially mandate and mainstreamed the most predatory version possible, and the states are not realizing their promised revenues.

There exist contact lenses that only need to be changed every few weeks, and the report is they feel like normal contacts.

Cate Hall explains why agency is both a trainable skill and also Definitely a Thing distinct from ‘success,’ and that if you don’t want your future successes to be in air quotes, you should go build that skill.

Cate Hall also points out that while you may be high agency in some ways, that does not mean you are automatically high agency in other ways. In many ways you likey are not actually trying. In particular, you’re likely stuck on whatever level of resourcefulness you had when you first encountered a given problem, which I’d raise to you likely being stuck with the particular strategies you found. You don’t step back and treat problems in other spheres the way you do in your areas of focus, even if you are exerting a lot of effort it is often not well-aimed or considered.

Denmark repeals its ban on nuclear energy.

Citrini: A handy guide to figuring out whether your thesis will pay off, based on your initial reaction:

“this is so fucking clever” – works maybe 10% of the time, likely drawdown before it does

“well…yeah, that’s fucking obvious” – best trade you’ll ever have in your life.

Deep Dish Enjoyer: buy the company producing the best llm on the market for under a 20 p/e.

The source tweet from George here plays it up too much but there is as one would expect a substantial (r~0.4) correlation between honesty and humility. From what I can tell all the ‘good’ personality traits correlate and so do all the bad ones. That’s very helpful in many ways, including getting a read on people.

Chinese attempt to recruit and blackmail fed official John Rogers, largely through the Chinese wife he found on a matchmaking service, likely thinking Rogers had far more access to actionable information than he did. As Tyler Cowen says, there probably wasn’t much to learn from him. It seems the Chinese pushed the threats too hard, and he reported their attempts to the Fed.

Lie detection is something we’re actually pretty good at if we pay attention.

David Parrell: One way to sense if somebody’s telling the truth is that there’s a freshness to their words, whereas people who are lying speak in platitudes and tell you what they think they’re supposed to tell you.

This is also a way to investigate your own thinking. We can so easily fool ourselves without realizing it. But when our words feel recycled and repackaged, it’s a sign that we’re deceived, or at the very least, not being entirely honest with ourselves.

Yes And: A good therapist can smell this in seconds.

This is true if and only if the cheerfulness doesn’t interfere with something load bearing, which can be true in unexpected ways sometimes, hence missing mood:

Tetraspace: I don’t really believe in missing moods but I do believe in the nearby concept of stop celebrating the costs.

If something is worth doing it’s worth being cheerful about (you don’t have to be cheerful, but it’s worth cheer). But a lot of things that are worth doing hurt people, and the people being hurt are costs, not benefits, and the cause of the cheer is the benefits, not the costs.

There are two levels to missing moods.

The first level, where everyone here is in violent agreement, is not to celebrate the need to pay costs, and not to confuse costs with benefits.

The second level, which can play back into confusions on the first level, is that you need the missing moods because that is how humans track such things, and how we generate reward signals to fine-tune our brains. You should generate such signals deliberately and ensure that they train your brain in ways that you prefer.

Jane Street was excellent about this. They emphasized the situations in which you ‘should be sad’ about something, versus happy, exactly enough to remind your brain that something was a negative and it we should evaluate and update accordingly. This is part of deliberate practice at all levels, in all things. You need to pay that experiential price, to some extent, to get the results.

Whereas there are other situations in which doing something cheerfully is the action that is load bearing. It is always a little bit load bearing in that you would prefer to be cheerful rather than not, and those around you usually also prefer this. Some actions only work if you are cheerful while doing them or otherwise have the right attitude, or at least they work far better. Those are almost always either worth doing cheerfully, or not worth doing at all.

The trick then is that this conflicts with a well-calibrated brain that systematizes deliberate practice. You need to be able to shut off those functions, in whole or in part, for the moment, while retaining them for other purposes. That’s tricky to do, and a tricky balance to get right even once you have the power to do it.

If you’re a young woman at a prestigious university there are those who will pay top dollar, tends of thousands, for your eggs. One comment says they offered $200k. Thanks, people warning about this ‘predatory advertising’ of (for some, it’s an offer, you can turn it down!) the ultimate win-win-win trade. There’s a real health cost, but in every other way I say you’re doing a very obviously good thing, and if you disagree you can just pass on this.

Tetraspace: If only I could be so exploited!

Kelsey Piper: I also got these ads and looked into the process! It didn’t happen to work out but I’m glad I was offered the opportunity. Graduate students aren’t children; the serious moral considerations occurred to me and I thought about them; and I value helping people start families.

The absurd culture of infantalization and helplessness of grown adults where we are appalled at the idea of a 22 year old graduate student making a serious, major life choice sickens me. 22 year olds can marry! They can have children! They make many decisions of serious import.

Part of living in our world is that there will be a great many opportunities to make decisions that really matter and that you feel unequipped for. Make them, or don’t, but the world spins on – that’s adulthood, and it’s grotesque to complain it was expected of you.

A graduate student at Yale is also offered the opportunity to make absurd sums of money working in various industries of at least dubious ethical standing. Should we go ‘poor Yale babies, how could they resist the predatory management consulting offers’? No! They should grow up.

If you went to Yale, you have lying before you manifest opportunities to affect the world for good and for ill, to create life and to design new weaponry, to be an egg donor or a crypto sports betting founder. You’re not a helpless baby being preyed on.

It is your obligation- and I’m not saying it’s an easy obligation, just that bioethicists cannot shield you from it- to figure out what you believe is right and pursue it, and refuse temptations to do wrong. The world can’t provide this, won’t provide this, and frankly shouldn’t.

Noah Smith claims American culture has stagnated.

He starts off citing the standard evidence like movies being dominated by sequels and music being dominated by older songs and the top Broadway shows being revivals and old brands (e.g. DC and Marvel) dominating comics. He also cites the standard counterexample that TV has very clearly experienced a golden age – I strongly agree and observe that with notably rare exceptions older shows now appear remarkably bad even when you get to skip commercials.

I’d also defend Broadway and music consumption mostly being old. Why shouldn’t they be? A time-honored Broadway play is proven to be good, it makes sense to do a lot of exploitation along with the exploration, and we do find new big hits like The Book of Mormon and Hamilton. In music it is even more obviously correct to do mostly exploitation, or exploration of the past where selection has done its job over time, in at-home experiences. In addition, when you play the classics, you get the benefits of a rich tradition, that adds to the experience and builds a common culture and language. I say that’s good, actually. Is it ‘cultural stagnation’ when we read old books? Or is that what leads to culture?

And also there are completely new, rapidly evolving forms of culture, that flat out didn’t exist before, as he notes Katherine Dee arguing. A lot of it is slop, but that’s always been true everywhere, and they are largely what you make of them. Even in a 90%+ (or even 99%+!) slop world, search and filters can work wonders.

Noah considers response to technology, and also has a theory of possibility exhaustion, that the low-hanging fruit has been picked. There are only so many worthy chords, so many good plots. He thinks this is a lot of why movies now are so repetitive, the space of movies is too small.

Noah and I basically agree on what’s going on in another way. Movie people used to largely make movies for each other. The sequels were (I think) always what audiences actually wanted, and the creatives basically refused to deliver and now they’ve stopped refusing. But there’s still plenty of room for the avant-garde and making a ‘good’ ‘original’ movie.

Also, we’re seeing a lot of cultural change start to happen because of AI, which will only accelerate. I’m definitely not worried about ‘cultural stagnation’ going forward.

Tyler Cowen responds that he is inclined to blame what stagnation we do see on lack of audience taste today. I would reframe most of that complaint as saying that before we used to get to overrule or dictate audience taste far more than we do now, with a side of modern audiences having very little patience, which I mostly think they are right about.

Scott Sumner rattles off some overlooked films, predictably I have seen very few of them. Those that I did see seem like at least good picks but not exceptional picks, and of course my choice to see those in particular wasn’t random. There’s a Letterboxd version.

What type of music you like predicts your big 5 personality traits, some details surprised me but they all made sense after I thought about them for a few seconds.

Are the music recommendation engines the problem, or is this an unreasonable ask? I think the answer is both, we are trying to solve the wrong problems using the wrong methods using a wrong model of the world and all our mistakes are fail to cancel out.

David Perell: It’s strange, but I almost never discover my favorite music on Spotify. The songs I fall in love with are always the ones I hear when I’m out. The ones friends show me. The ones I hear at coffee shops. Or a night out. I would’ve expected personalized algorithms to constantly show me songs I fall in love with, but that hasn’t happened.

Erik Hoffman: That’s why recommendations will always suck if they do not include data such as time of year, weather, season of life etc into the algorithms

Matthew Kobach: This isn’t because the algorithms are bad per se, it’s because context matters. Spotify can play the right song, but if it’s the wrong time or context, you’ll never love it.

Your favorite songs are inextricably tied to emotion, even if you’ve long forgotten the original emotion.

Brett Iredale: Been saying this for years. Spotify is obsessed with giving you more of what you’ve already listened to – not focused on new things you might like. I will jump ship the second there is a new product with a better recommendation algo.

Allen Walton: Was at Starbucks 2 years ago. Empty, raining outside, just espresso sounds. Song came on I’d never heard before.

“Cats and dogs are coming down… 14th street is gonna drown.”

It got my attention and I enjoyed the whole song, so IIooked up the band (Nada Surf). Ended up loving their music and now I’m a huge fan. Saw them live a couple months ago, was excellent.

If the algos worked, I would have been enjoying them the last 20 years!

Clint Murphy: Spotify will find songs you like.

The songs you love, though, usually have something different than what you like.

They’re often songs, as you say, in a moment. With an experience. They fill something in you at that moment and Spotify or any Algo, so far, doesn’t know that moment.

AI tied to your everyday life, and body metrics, will get there.

-

An algorithm like Spotify is simply not trying to find unique music you will love. That’s not what it is being optimized to do. It is trying to go ‘here is Some Music, you could listen to that’ such that you go ‘okay, that is indeed Some Music, I could listen to that.’ This is not a terrible thing to do, but it is not where most value lies.

-

Simply put, the algorithms are not yet that good. They are good enough to say ‘here is Some Music’ or ‘here is Some Music that closely matches your existing choices of music’ but not at making interesting leaps.

-

Most value lies in big successes: You find a song, album or artist (or even entire genre) you then love. By its nature, searches for this on the margin are going to have a low hit rate.

-

The priming is very important, as is the feeling of curation and scarcity. You really benefit from association and serendipity. I will often find good stuff from a TV show, or a game, or a movie, or yes a song I heard in some circumstance. Of course, if a song really is good enough, you can make that happen afterwards, but to be a song you love it has to mean something.

-

The algorithms not only can’t set the context, they don’t understand the context, as Hoffman points out. This one is going to be a tough nut to crack.

-

The collective music world is actually scary good at finding the best stuff once you adjust for context. I am currently doing a ‘grand tour’ of every artist for whom my music library contains at least one song and wow, the popularity rankings within each artist are scary accurate. They can miss something great via not noticing, but even that is rarer than you think. There are places the public makes bad picks or had its chance and missed, but it’s always surprising, and usually even when I disagree I understand why. In most cases I realize that yes, I am in general wrong, this song is great for me (or lousy for me) but not in general.

-

The algorithm moves last, after you’ve tried everything else. This subjects it to adverse selection.

There’s a lot of room to do better for power users, but Spotify has to work with users who, like users everywhere, are mostly maximally lazy and who don’t want to invest. I’m actually not so sure there’s much room to improve there, although I use Amazon Music rather than Spotify so I haven’t put it to the test.

Benjamin Hoffman offers a thread on the 1990s and why people are so nostalgic for them. Here’s part of it.

Benjamin Hoffman: The big movies of 1999 were expressions of desperation at the false bourgeois we’d constructed to replace the real one – Office Space, Fight Club, American Beauty, and The Matrix, which spookily resembled the Columbine High School massacre.

The Matrix also specifically and correctly predicted that we’d try to replay the ‘90s over and over to keep the simulation going instead of getting on with our lives. The best Office Space could recommend was becoming a laborer.

It makes more sense to think of the ‘90s as the last decade in which a relatively sheltered person might not realize that society was systematically breaking its implied commitments to people who worked hard & played by the rules.

I notice that those are the ones that I loved and remember and seem important, but only 2 of those 4 are in the top 10 grossing movies of the year.

The listed category also would include Magnolia, and arguably also in a way the highest grossing movies of the year if you take them properly seriously, which were Star Wars Episode I about the fall of a republic that had lost its virtue in peacetime and how we ultimately turn to the dark side, The Sixth Sense about (spoiler but come on) and Toy Story 2 about being trapped by a collector and preserved in a box. Then #4 is The Matrix, and #5 is Tarzan, which glamorizes being outside of society, and #7 is Notting Hill which is basically about rejecting modernity for an old bookshop. Huh.

I still think of 1999 as a high water mark in movies. Those were good times.

(As a control I randomly chose 2005 and didn’t see the same pattern, also most of the top films were now some sort of remake. Then I went to 2012 and we’re in a wasteland of franchises that have nothing to say.)

A comment on my call for the Meta-Subscription, saying it exists and it’s YouTube:

Joe Barton: “I continue to think that a mega subscription is The Way for human viewing. Rather than pay per view, which feels bad, you pay for viewing in general, then the views are incremented, and the money is distributed based on who was viewed.”

I’ve been a YouTube Red/Premium subscriber since basically day one. I know you go on and on about how Google can’t market their way out of a used kleenex dropped in the street on a rainy day – This is Yet Another Example of that principle.

YouTube Premium is the mega subscription model you’re describing, and it already works brilliantly – Google just can’t market it to save their lives.

Nobody and I mean NOBODY (except The Spiffing Brit in one throwaway line in one video¹) realizes that YouTube splits Premium subscription revenue 55/45 with creators, just like ad revenue. But here’s the kicker: it fundamentally changes the entire ecosystem. Instead of viewers being the product sold to advertisers, we become the customers. Creators get paid MORE per Premium view than ad views, without worrying about “advertiser-friendly” content guidelines. I never get that “feels bad” moment of deciding if a video is worth X cents – I just watch what interests me, guilt-free.

The model removes ALL the friction: no ads, no ad-blocker wars, creators get stable income, and viewers can support creators without thinking about it. YouTube Premium is proof that the mega subscription model works. The only failure is that after nearly a decade, Google still hasn’t figured out how to explain this to people. They’ve positioned it as “YouTube without ads” when it’s actually “become a patron of every creator you watch, automatically.”

¹ Explained briefly from 1: 24 to 2: 40 in “YouTube Premium Is Broken.” by The Spiffing Brit, 14 August 2021. “Most creators see basically no revenue from Premium each month.”

I too am a YouTube Premium subscriber, and no I did not realize that my viewing was subsidizing creators more than I would have without the subscription. I only knew not having ads was worth a lot. And yes, YouTube has quite a lot in it, but no it is not the Mega-Subscription even for video. Too many others aren’t playing ball.

A rare time when explaining the joke actually is pretty funny.

ESPN finally launches a streaming service. Ben Thompson correctly says ‘finally’ but also notes that everyone is worse off now that sports along with everything else can only be watched intentionally through a weird mix of streaming services. The problem with ESPN as a streaming service is that it won’t actually give you what you want. If you offered me the Sports Streaming Service (SSS), and it had All The Sports, I’d be down for paying a decently large amount. Give me a clean way to subscribe even just to the teams I want, and maybe that works until the playoffs. But if I’m going to be in I want to be in. ESPN alone doesn’t get me in and I don’t want to spend the time figuring out where everything is. So it’s still going to be YouTubeTV for football season and that’s it, I suppose.

Alas, there’s been no time for me to game this month. I hope to get back to it soon.

I am on the fence about getting back to Blue Price. I do think it’s pretty great in many ways, but not sure it’s my speed and I worry about being puzzle-locked or waiting for a lucky day?

Next up: Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, which everyone loves but I haven’t played yet past the first campfire, and Monster Train 2 which is a ticket I can cash at any time.

And of course Slay the Spire 2, once it arrives.

So instead we have to live vicariously through Magic: The Gathering news.

We now have Magic: the Gathering Standard set built around Final Fantasy? Sign me up! Except actually, no, don’t, and not only because look at the time.

The same way that the Dungeons & Dragons set ‘got’ D&D, the Final Fantasy set mostly doesn’t ‘get’ Final Fantasy, or its particular concepts and characters. There are some clear hits for me, especially Cecil, Dark Knight. But there’s also a ton of ‘look at what they did to my boy.’ Or my girl, Aerith, the vibes are almost reversed. You think that’s Tifa? You think that’s what happens when Kefka transforms? Cloud triggers equipment twice rather than being able to lift his sword at all? The Crystal’s Chosen happens on turn seven? What is even going on with Sin?

I could go on.

Mechanically the set feels schitzo. Which is kind of fine in principle, since Final Fantasy is kind of schitzo and I love it to pieces (in order especially 6, 4 and 7, but I’ve also played through and endorse 12, 1, 10, 8, 3 and 2) you’re doing the entire franchise, but then the resonance mostly feels backwards. We object because we care.

(I don’t know why I bounced off 9, whereas 5 felt like an uber grind and my first attempt got into a nightmare spot in the endgame, must have been doing it wrong. X-2’s opening was insane in the best way but it kind of petered out. I endorse that 13 and 15 weren’t doing the thing anymore, sad, and haven’t tried 16. The MMORPGs don’t count, I tried 14 for a few hours and it felt highly mid.)

I don’t follow Magic right now so I have no direct data on if Prowess is too good in Standard, but Sam Black seems clearly right that if you hold a bunch of major Arena tournaments and no one can beat the best deck there, then that means the best deck is too good, what else were you even hoping for? Arena regular play, including at high Mythic, systematically is both much easier than big tournaments for other reasons and also includes a lot more people experimenting or trying to beat the best deck, and less people playing the best deck.

With distance from the game, I think Magic in general has been way way too reluctant to drop ban hammers. Yes, it’s annoying to strike down people’s cards and decks, but it’s far worse for your game to suck for a while, and for everyone to feel forced to fall in line. In the Arena era, things go faster, no one is holding big secrets back for long, and you find out fast if you have a problem.

Sam Pardee: Playing on Arena before the RC I played against a ton of MD High Noons and Authority of the Consuls. The notion that players aren’t trying and “immediately crying for changes” is laughable to me.

…