Windows’ original Secure Boot certificates expire in June—here’s what you need to do

The second thing to check is the “default db,” which shows whether the new Secure Boot certificates are baked into your PC’s firmware. If they are, even resetting Secure Boot settings to the defaults in your PC’s BIOS will still allow you to boot operating systems that use the new certificates.

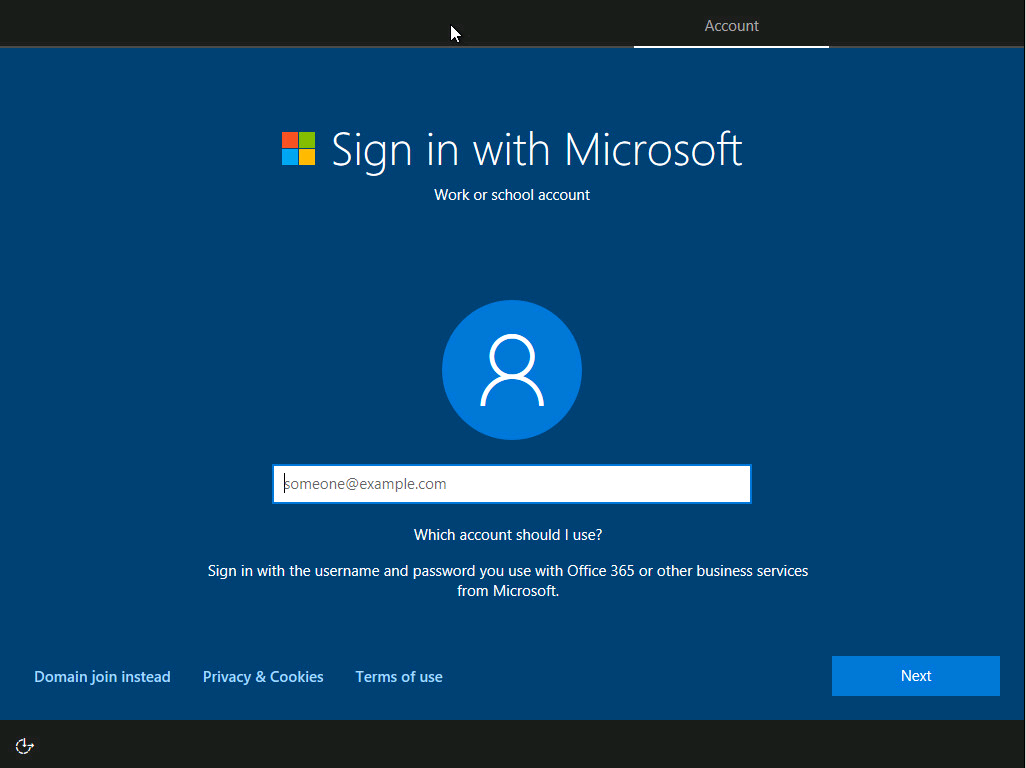

To check this, open PowerShell or Terminal again and type ([System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString((Get-SecureBootUEFI dbdefault).bytes) -match 'Windows UEFI CA 2023'). If this command returns “true,” your system is running an updated BIOS with the new Secure Boot certificates built in. Older PCs and systems without a BIOS update installed will return “false” here.

Microsoft’s Costa says that “many newer PCs built since 2024, and almost all the devices shipped in 2025, already include the certificates” and won’t need to be updated at all. And PCs several years older than that may be able to get the certificates via a BIOS update.

In the US, Dell, HP, Lenovo, and Microsoft all have lists of specific systems and firmware versions, while Asus provides more general information about how to get the new certificates via Windows Update, the MyAsus app, or the Asus website. The oldest of the PCs listed generally date back to 2019 or 2020. If your PC shipped with Windows 11 out of the box, there should be a BIOS update with the new certificates available, though that may not be true of every system that meets the requirements for upgrading to Windows 11.

Microsoft encourages home users who can’t install the new certificates to use its customer support services for help. Detailed documentation is also available for IT shops and other large organizations that manage their own updates.

“The Secure Boot certificate update marks a generational refresh of the trust foundation that modern PCs rely on at startup,” writes Costa. “By renewing these certificates, the Windows ecosystem is ensuring that future innovations in hardware, firmware, and operating systems can continue to build on a secure, industry‐aligned boot process.”

Windows’ original Secure Boot certificates expire in June—here’s what you need to do Read More »