Newest Starship booster is significantly damaged during testing early Friday

Friday morning’s failure was less energetic than an explosion of a Starship upper stage during testing at Massey’s in June. That incident caused widespread damage at the test site and a complete loss of the vehicle. The Booster 18 problem on Friday appeared to cause less damage to test infrastructure, and no Raptor engines had yet been installed on the vehicle.

Nevertheless, this is the point in the rocket development program at which SpaceX sought to be accelerating with development of Starship and reaching a healthy flight cadence in 2026. Many of the company’s near-term goals rely on getting Starship flying regularly and reliably.

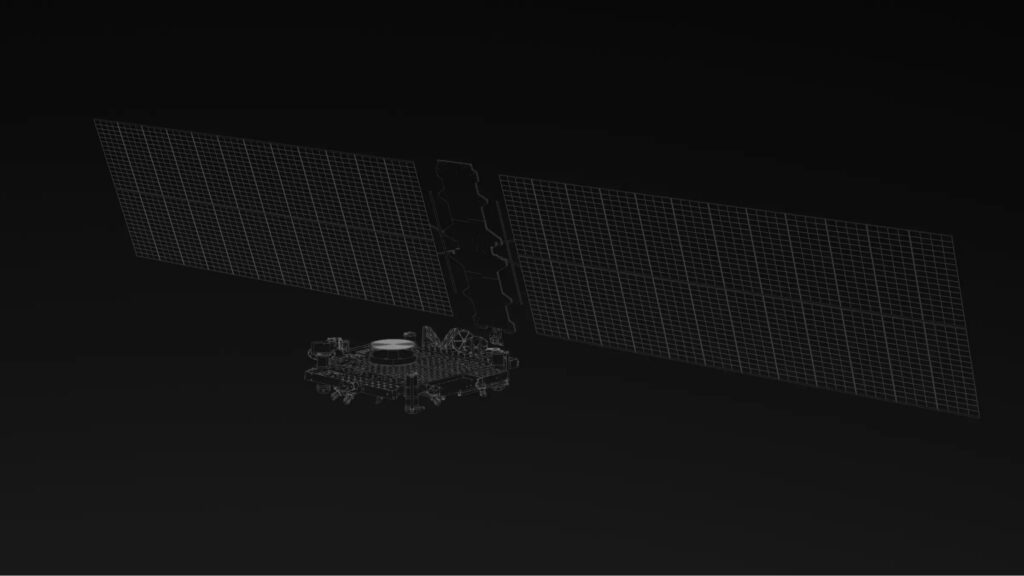

A full view of super heavy booster 18’s catastrophic damage during testing tonight. Very significant damage to the entire LOX tank section.

11/21/25 pic.twitter.com/Kw8XeZ2qXW

— Starship Gazer (@StarshipGazer) November 21, 2025

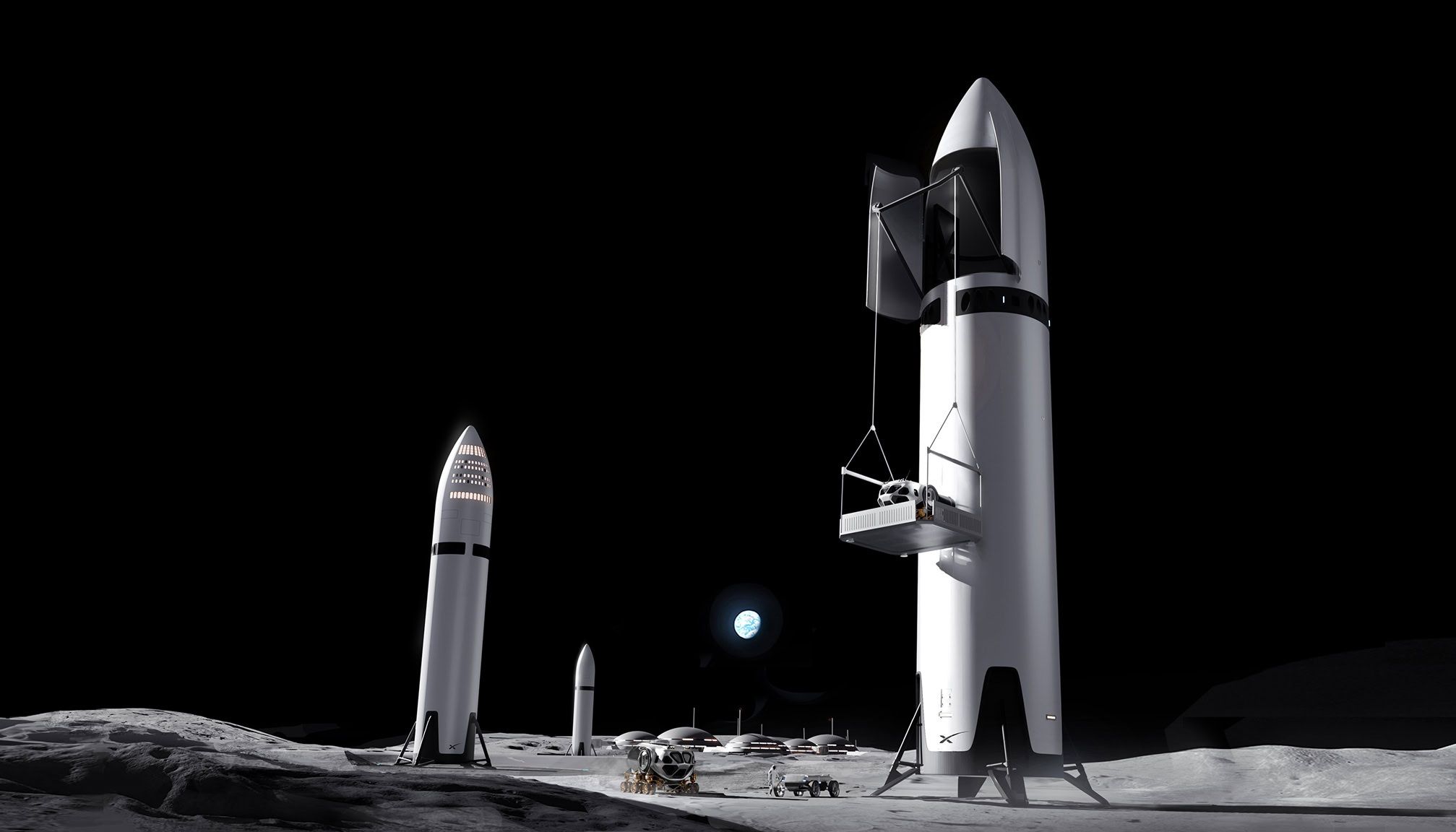

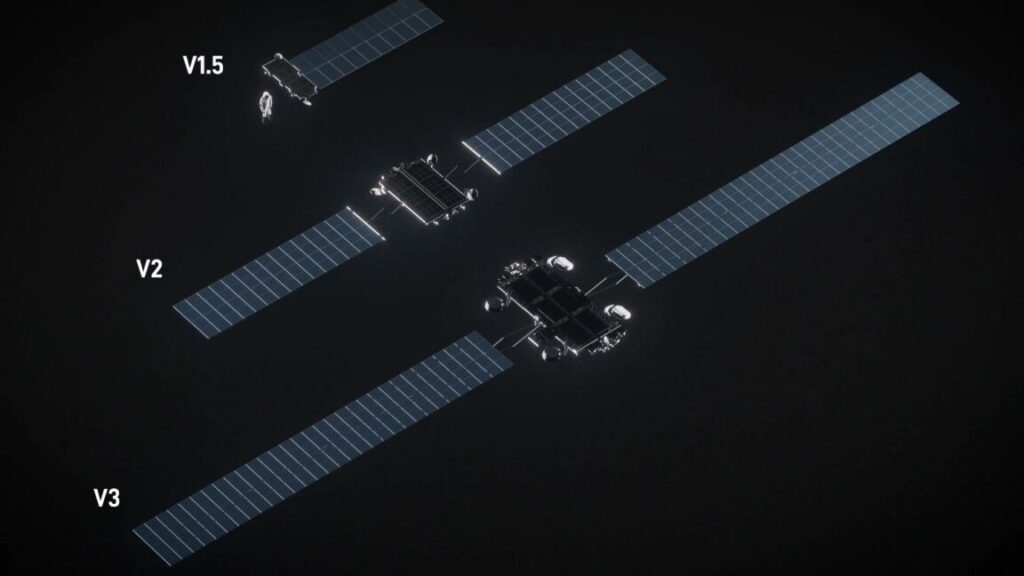

With this upgraded vehicle, SpaceX wants to demonstrate booster landing and reuse, an upper stage tower catch next year, the beginning of operational Starlink deployment missions, and a test campaign for NASA’s Artemis Program. To keep this Moon landing program on track, it is critical that SpaceX and NASA conduct an on-orbit refueling test of Starship, which nominally was slated for the second half of 2026.

On this timeline, the company was aiming to conduct a crewed lunar landing for NASA during the second half of 2028. From an outside perspective, before this most recent failure, that timeline already seemed to be fairly optimistic.

One of the core attributes of SpaceX is that it diagnoses failure quickly, addresses problems, and gets back to flying as rapidly as possible. No doubt its engineers are already poring over the data captured Friday morning and quite possibly have already diagnosed the problem. The company is resilient, and it has ample resources.

Nevertheless, this is also a maturing program. The Starship vehicle launched for the first time in 2023, and its first stage made a successful flight two years ago. Losing the first stage of the newest generation of the vehicle, during the initial phases of testing, can only be viewed as a significant setback for a program with so much promise and so much to accomplish so soon.

Newest Starship booster is significantly damaged during testing early Friday Read More »