Why would Elon Musk pivot from Mars to the Moon all of a sudden?

As more than 120 million people tuned in to the Super Bowl for kickoff on Sunday evening, SpaceX founder Elon Musk turned instead to his social network. There, he tapped out an extended message in which he revealed that SpaceX is pivoting from the settlement of Mars to building a “self-growing” city on the Moon.

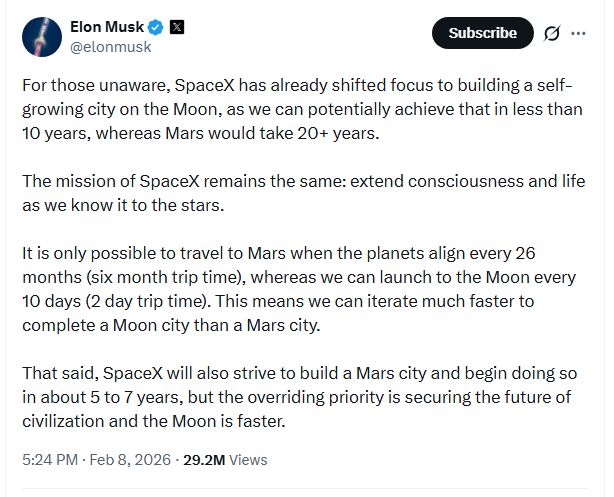

“For those unaware, SpaceX has already shifted focus to building a self-growing city on the Moon, as we can potentially achieve that in less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years,” Musk wrote, in part.

Elon Musk tweet at 6: 24 pm ET on Sunday. Credit: X/Elon Musk

This is simultaneously a jolting and practical decision coming from Musk.

Why it’s a jolting decision

A quarter of a century ago, Musk founded SpaceX with a single-minded goal: settling Mars. One of his longest-tenured employees, SpaceX President and Chief Operating Officer Gwynne Shotwell, described her very first interview with Musk in 2002 to me as borderline messianic.

“He was talking about Mars, his Mars Oasis project,” Shotwell said. “He wanted to do Mars Oasis, because he wanted people to see that life on Mars was doable, and we needed to go there.”

She was not alone in this description of her first interaction with Musk. The vision for SpaceX has not wavered. Even in the company’s newest, massive Starship rocket factory at the Starbase facility in South Texas—also known as the Gateway to Mars—there are reminders of the red planet everywhere. For example, the carpet inside Musk’s executive conference room is rust red, the same color as the surface of Mars.

In the last 25 years, Musk has gone from an obscure, modestly wealthy person to the richest human being ever, from a political moderate to chief supporter of Donald Trump; from a respected entrepreneur to, well, to a lot of things to a lot of people: world’s greatest industrialist/supervillain/savant/grifter-fraudster.

But one thing that has remained constant across the Muskverse is his commitment to “extending the light of human consciousness” and to the belief that the best place to begin humanity’s journey toward becoming a multi-planetary species was Mars.

Why would Elon Musk pivot from Mars to the Moon all of a sudden? Read More »