Rocket Report: China launches refueling demo; DoD’s big appetite for hypersonics

We’re just a few days away from getting a double-dose of heavy-lift rocket action.

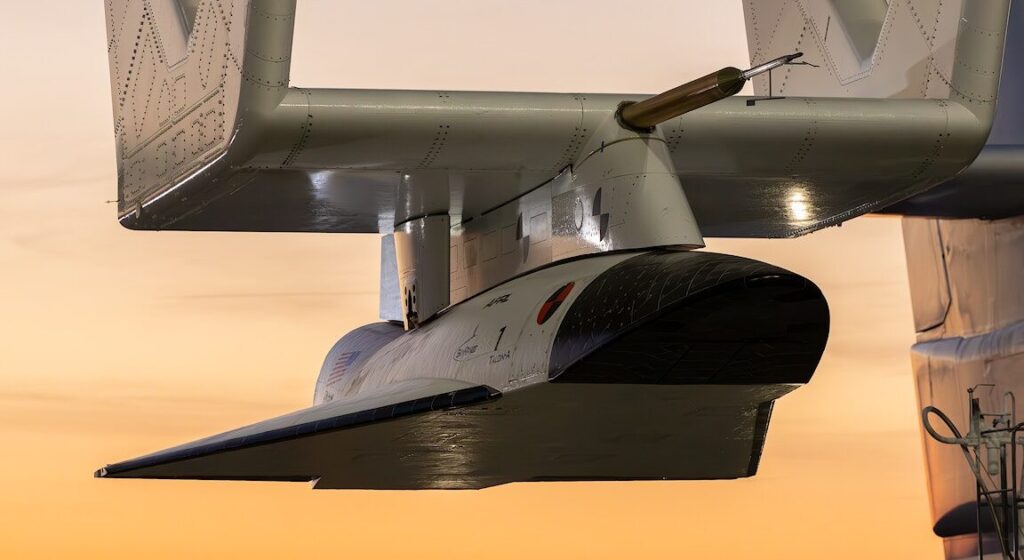

Stratolaunch’s Talon-A hypersonic rocket plane will be used for military tests involving hypersonic missile technology. Credit: Stratolaunch

Welcome to Edition 7.26 of the Rocket Report! Let’s pause and reflect on how far the rocket business has come in the last 10 years. On this date in 2015, SpaceX made the first attempt to land a Falcon 9 booster on a drone ship positioned in the Atlantic Ocean. Not surprisingly, the rocket crash-landed. In less than a year and a half, though, SpaceX successfully landed reusable Falcon 9 boosters onshore and offshore, and now has done it nearly 400 times. That was remarkable enough, but we’re in a new era now. Within a few days, we could see SpaceX catch its second Super Heavy booster and Blue Origin land its first New Glenn rocket on an offshore platform. Extraordinary.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

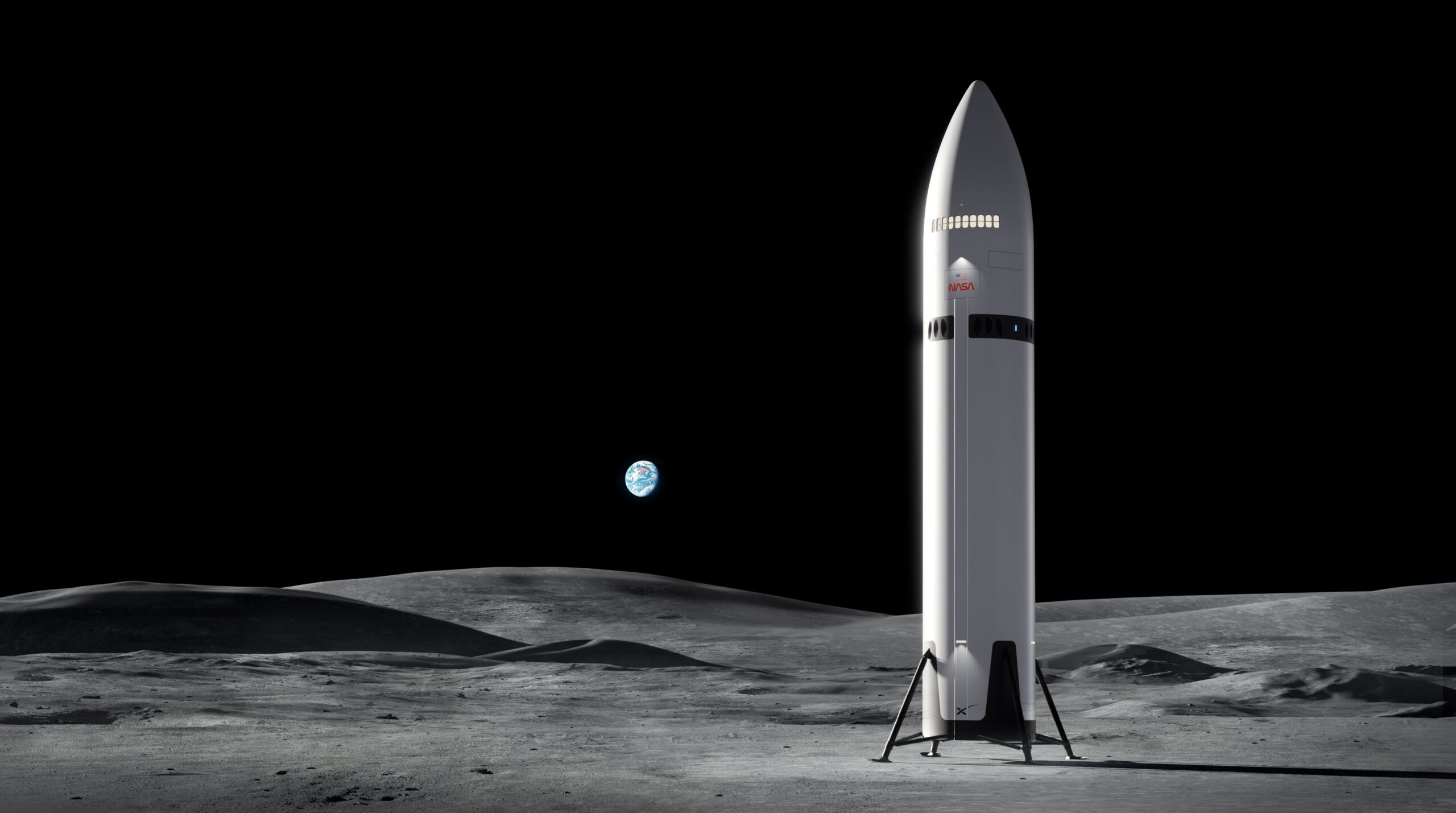

Our annual ranking of the top 10 US launch companies. You can easily guess who made the top of the list: the company that launched Falcon rockets 134 times in 2024 and launched the most powerful and largest rocket ever built on four test flights, each accomplishing more than the last. The combined 138 launches is more than NASA flew the Space Shuttle over three decades. SpaceX will aim to launch even more often in 2025. These missions have far-reaching impacts, supporting Internet coverage for consumers worldwide, launching payloads for NASA and the US military, and testing technology that will take humans back to the Moon and, someday, Mars.

Are there really 10? … It might also be fairly easy to rattle off a few more launch companies that accomplished big things in 2024. There’s United Launch Alliance, which finally debuted its long-delayed Vulcan rocket and flew two Atlas V missions and the final Delta IV mission, and Rocket Lab, which launched 16 missions with its small Electron rocket this year. Blue Origin flew its suborbital New Shepard vehicle on three human missions and one cargo-only mission and nearly launched its first orbital-class New Glenn rocket in 2024. That leaves just Firefly Aerospace as the only other US company to reach orbit last year.

DoD announces lucrative hypersonics deal. Defense technology firm Kratos has inked a deal worth up to $1.45 billion with the Pentagon to help develop a low-cost testbed for hypersonic technologies, Breaking Defense reports. The award is part of the military’s Multi-Service Advanced Capability Hypersonic Test Bed (MACH-TB) 2.0 program. The MACH-TB program, which began as a US Navy effort, includes multiple “Task Areas.” For its part, Kratos will be tasked with “systems engineering, integration, and testing, to include integrated subscale, full-scale, and air launch services to address the need to affordably increase hypersonic flight test cadence,” according to the company’s release.

Multiple players … The team led by Kratos, which specializes in developing airborne drones and military weapons systems, includes several players such as Leidos, Rocket Lab, Stratolaunch, and others. Kratos last year revealed that its Erinyes hypersonic test vehicle successfully flew for a Missile Defense Agency experiment. Rocket Lab has launched multiple suborbital hypersonic experiments for the military using a modified version of its Electron rocket, and Stratolaunch reportedly flew a high-speed test vehicle and recovered it last month, according to Aviation Week & Space Technology. The Pentagon is interested in developing hypersonic weapons that can evade conventional air and missile defenses. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

ESA will modify some of its geo-return policies. An upcoming European launch competition will be an early test of efforts by the European Space Agency to modify its approach to policies that link contracts to member state contributions, Space News reports. ESA has long used a policy known as geo-return, where member states are guaranteed contracts with companies based in their countries in proportion to the contribution those member states make to ESA programs.

The third rail of European space … Advocates of geo-return argue that it provides an incentive for countries to fund those programs. This incentivizes ESA to lure financial contributions from its member states, which will win guaranteed business and jobs from the agency’s programs. However, critics of geo-return, primarily European companies, claim that it creates inefficiencies that make them less competitive. One approach to revising geo-return is known as “fair contribution,” where ESA first holds competitions for projects, and member states then make contributions based on how companies in their countries fared in the competition. ESA will try the fair contribution approach for the upcoming launch competition to award contracts to European rocket startups. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

RFA is building a new rocket. German launch services provider Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) is currently focused on building a new first stage for the inaugural flight of its RFA One rocket, European Spaceflight reports. The stage that was initially earmarked for the flight was destroyed during a static fire test last year on a launch pad in Scotland. In a statement given to European Spaceflight, RFA confirmed that it expects to attempt an inaugural flight of RFA One in 2025.

Waiting on a booster … RFA says it is “fully focused on building a new first stage and qualifying it.” The rocket’s second stage and Redshift OTV third stage are already qualified for flight and are being stored until a new first stage is ready. The RFA One rocket will stand 98 feet (30 meters) tall and will be capable of delivering payloads of up to 1.3 metric tons (nearly 2,900 pounds) into polar orbits. RFA is one of several European startups developing commercial small satellite launchers and was widely considered the frontrunner before last year’s setback. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Pentagon provides a boost for defense startup. Defense technology contractor Anduril Industries has secured a $14.3 million Pentagon contract to expand solid-fueled rocket motor production, as the US Department of Defense moves to strengthen domestic manufacturing capabilities amid growing supply chain concerns, Space News reports. The contract, awarded under the Defense Production Act, will support facility modernization and manufacturing improvements at Anduril’s Mississippi plant, the Pentagon said Tuesday.

Doing a solid … The Pentagon is keen to incentivize new entrants into the solid rocket manufacturing industry, which provides propulsion for missiles, interceptors, and other weapons systems. Two traditional defense contractors, Northrop Grumman and L3Harris, control almost all US solid rocket production. Companies like Anduril, Ursa Major, and X-Bow are developing solid rocket motor production capability. The Navy previously awarded Anduril a $19 million contract last year to develop solid rocket motors for the Standard Missile 6 program. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Relativity’s value seems to be plummeting. For several years, an innovative, California-based launch company named Relativity Space has been the darling of investors and media. But the honeymoon appears to be over, Ars reports. A little more than a year ago, Relativity reached a valuation of $4.5 billion following its latest Series F fundraising round. This was despite only launching one rocket and then abandoning that program and pivoting to the development of a significantly larger reusable launch vehicle. The decision meant Relativity would not realize any significant revenue for several years, and Ars reported in September on some of the challenges the company has encountered developing the much larger Terran R rocket.

Gravity always wins … Relativity is a privately held company, so its financial statements aren’t public. However, we can glean some clues from the published quarterly report from Fidelity Investments, which owns Relativity shares. As of March 2024, Fidelity valued its 1.67 million shares at an estimated $31.8 million. However, in a report ending November 29 of last year, which was only recently published, Fidelity’s valuation of Relativity plummeted. Its stake in Relativity was then thought to be worth just $866,735—a per-share value of 52 cents. Shares in the other fundraising rounds are also valued at less than $1 each.

SpaceX has already launched four times this year. The space company is off to a fast start in 2025, with four missions in the first nine days of the year. Two of these missions launched Starlink internet satellites, and the other two deployed an Emirati-owned geostationary communications satellite and a batch of Starshield surveillance satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office. In its new year projections, SpaceX estimates it will launch more than 170 Falcon rockets, between Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, Spaceflight Now reports. This is in addition to SpaceX’s plans for up to 25 flights of the Starship rocket from Texas.

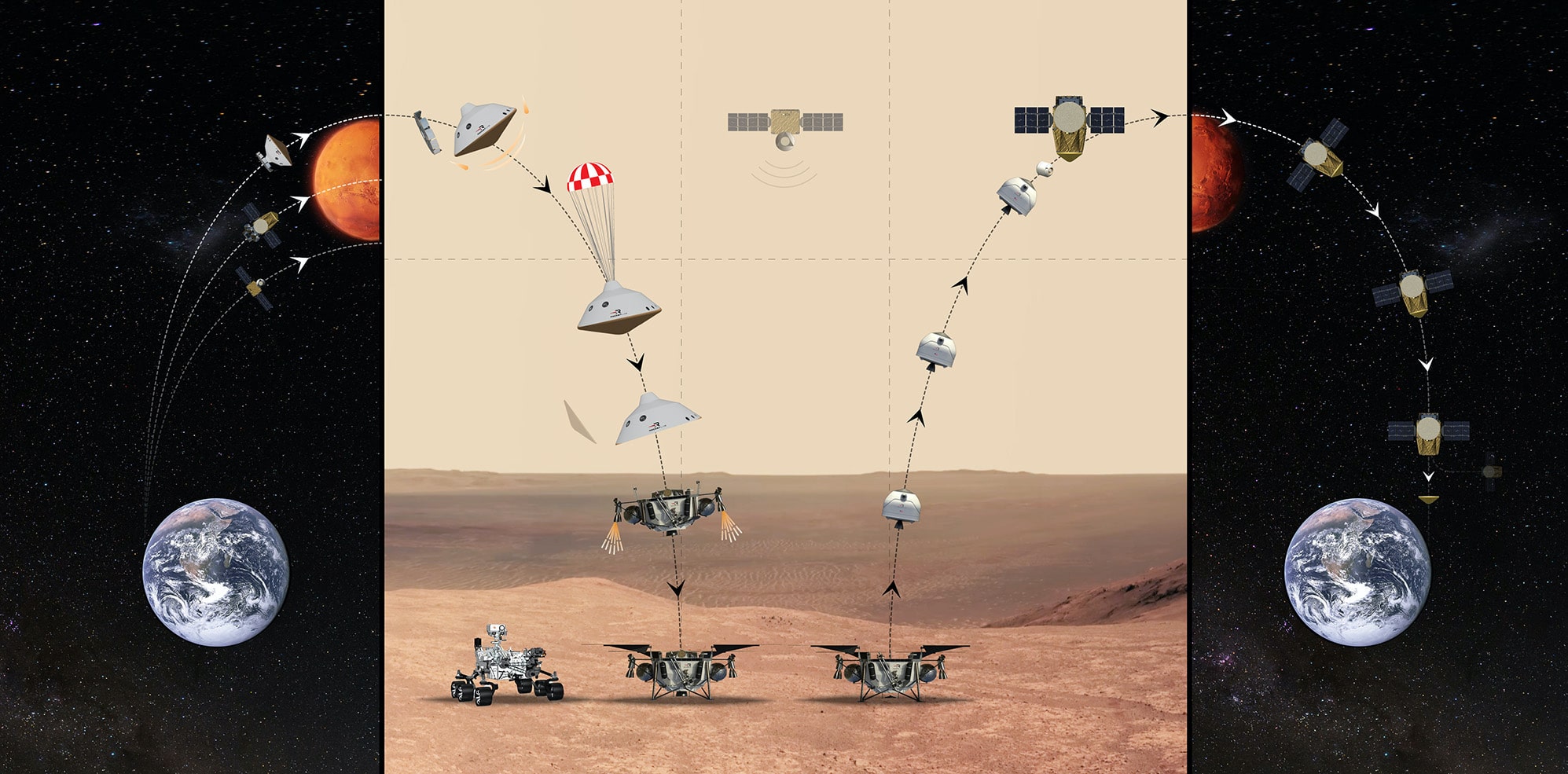

What’s in store this year?… Highlights of SpaceX’s launch manifest this year will likely include an attempt to catch and recover Starship after returning from orbit, a first in-orbit cryogenic propellant transfer demonstration with Starship, and perhaps the debut of a second launch pad at Starbase in South Texas. For the Falcon rocket fleet, notable missions this year will include launches of commercial robotic lunar landers for NASA’s CLPS program and several crew flights, including the first human spaceflight mission to fly in polar orbit. According to public schedules, a Falcon 9 rocket could launch a commercial mini-space station for Vast, a privately held startup, before the end of the year. That would be a significant accomplishment, but we won’t be surprised if this schedule moves to the right.

China is dipping its toes into satellite refueling. China kicked off its 2025 launch activities with the successful launch of the Shijian-25 satellite Monday, aiming to advance key technologies for on-orbit refueling and extending satellite lifespans, Space News reports. The satellite launched on a Long March 3B into a geostationary transfer orbit, suggesting the unspecified target spacecraft for the refueling demo test might be in geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator.

Under a watchful eye … China has tested mission extension and satellite servicing capabilities in space before. In 2021, China launched a satellite named Shijian-21, which docked a defunct Beidou navigation satellite and towed it to a graveyard orbit above the geostationary belt. Reportedly, Shijian-21 satellite may have carried robotic arms to capture and manipulate other objects in space. These kinds of technologies are dual-use, meaning they have civilian and military applications. The US Space Force is also interested in satellite life extension and refueling tech, so US officials will closely monitor Shijian-25’s actions in orbit.

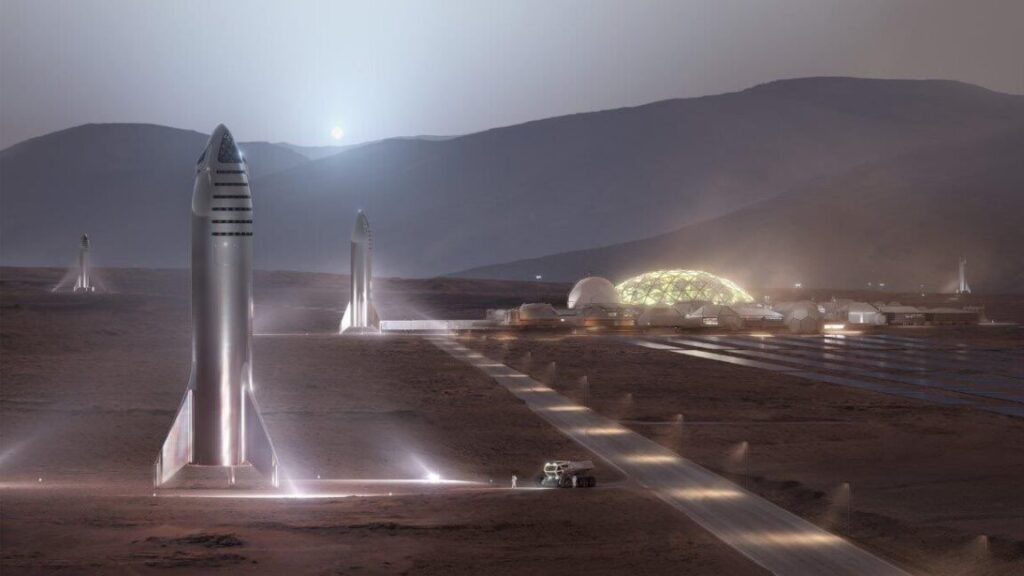

SpaceX set to debut upgraded Starship. An upsized version of SpaceX’s Starship mega-rocket rolled to the launch pad early Thursday in preparation for liftoff on a test flight next week, Ars reports. The rocket could lift off as soon as Monday from SpaceX’s Starbase test facility in South Texas. This flight is the seventh full-scale demonstration launch for Starship. The rocket will test numerous upgrades, including a new flap design, larger propellant tanks, redesigned propellant feed lines, a new avionics system, and an improved antenna for communications and navigation.

The new largest rocket … Put together, all of these changes to the ship raise the rocket’s total height by nearly 6 feet (1.8 meters), so it now towers 404 feet (123.1 meters) tall. With this change, SpaceX will break its own record for the largest rocket ever launched. SpaceX plans to catch the rocket’s Super Heavy booster back at the launch site in Texas and will target a controlled splashdown of the ship in the Indian Ocean.

Blue Origin targets weekend launch of New Glenn. Blue Origin is set to launch its New Glenn rocket in a long-delayed, uncrewed test mission that would help pave the way for the space venture founded by Jeff Bezos to compete against Elon Musk’s SpaceX, The Washington Post reports. Blue Origin has confirmed it plans to launch the 320-foot-tall rocket during a three-hour launch window opening at 1 am EDT (06: 00 UTC) Sunday in the company’s first attempt to reach orbit.

Finally … This is a much-anticipated milestone for Blue Origin and for the company’s likely customers, which include the Pentagon and NASA. Data from this test flight will help the Space Force certify New Glenn to loft national security satellites, providing a new competitor for SpaceX and United Launch Alliance in the heavy-lift segment of the market. Blue Origin isn’t quite shooting for the Moon on this inaugural launch, but the company will attempt to reach orbit and try to land the New Glenn’s first stage booster on a barge in the Atlantic Ocean. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Next three launches

Jan. 10: Falcon 9 | Starlink 12-12 | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 18: 11 UTC

Jan. 12: New Glenn | NG-1 Blue Ring Pathfinder | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 06: 00 UTC

Jan. 13: Jielong 3 | Unknown Payload | Dongfang Spaceport, Yellow Sea | 03: 00 UTC

Rocket Report: China launches refueling demo; DoD’s big appetite for hypersonics Read More »