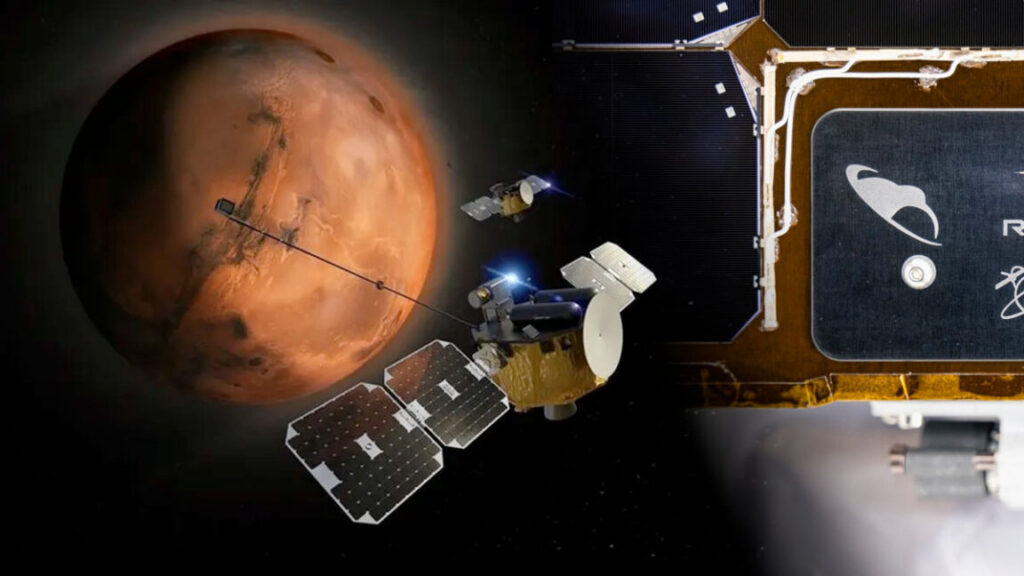

The twin probes just launched toward Mars have an Easter egg on board

The mission aims to aid our understanding of Mars’ climate history and what was behind the loss of its conditions that once supported liquid water, potential oceans, and possibly life on the surface.

Plaques and partner patches

In addition to the kiwi-adorned plates, Rocket Lab also installed two more plaques on the twin ESCAPADE spacecraft.

“There are also two name plates (one in blue and one in gold) on each spacecraft listing Rocket Lab team members who’ve contributed to the mission, making it possible to get to Mars,” said McLaurin.

Mounted on the solar panels, the plaques use shading to also display the Latin initials (NSHO) of the Rocket Lab motto and form the company’s logo. Despite their diminutive size, each plate appears to include more than 200 names, including founder, president, and CEO Peter Beck.

Additional plates in blue and gold display the names of the Rocket Lab team members behind the ESCAPADE spacecraft. Credit: UCB-SSL via collectSPACE.com

UC Berkeley adopted its colors in 1873. According to the school’s website, “blue for the California sky and ocean and for the Yale graduates who helped establish the university, gold for the ‘Golden State.’”

ESCAPADE also has its own set of colors, or rather, colorful patches.

The main mission logo depicts the twin spacecraft in orbit around Mars with the names of the primary partners listed along its border, including UCB-SSL (University of California, Berkeley-Space Science Laboratory); RL (Rocket Lab); ERAU (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, which designed and built the langmuir probe, one of the mission’s science instruments); AdvSp (Advanced Space, which oversaw mission design and trajectory optimization); and NASA-GSFC (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center).

Rocket Lab also designed an insignia, which renders the two spacecraft in blue and gold, as well as shows their trajectory in the same colors and includes the company’s motto.

Lastly, Blue Origin’s New Glenn-2 (NG-2) patch features the launch vehicle and the two ESCAPADE satellites, using hues of orange to represent Mars.

Three mission patches represent the Mars ESCAPADE mission and its partners. Credit: NASA/Rocket Lab/Blue Origin/collectSPACE.com

The twin probes just launched toward Mars have an Easter egg on board Read More »