Lunar Outpost celebrates release of Lego Moon Rover Space Vehicle

The set’s large, main futuristic rover with its rocker suspension, four-wheel steering, deployable solar panels, and rotating arm is not based on any specific vehicle Lunar Outpost is building now, but was inspired by the company’s plans.

More to come

“We have five lunar surface missions in total booked. One of the upcoming ones is really cool. It’s with the Australian Space Agency, so it will be Australia’s flagship lunar rover, which they affectionately call ‘Roo-ver,’ which I just love,” said Gemer.

Lunar Outpost’s next MAPP is targeted for launch in spring 2026. Using science instruments developed by NASA and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU APL), the rover will investigate a magnetic anomaly that has gone unexplained for hundreds of years.

“So those missions will be going, [but] we want to do bigger things, better things, more collaborative, robotic missions. We really want to be the foundational infrastructure on the Moon,” Gemer said. “Mobility is one of those key enablers to building big and exciting things like a permanent human presence on the moon. So that’s why we set out to be the leaders in space mobility, and I think that’s what we’ve accomplished.”

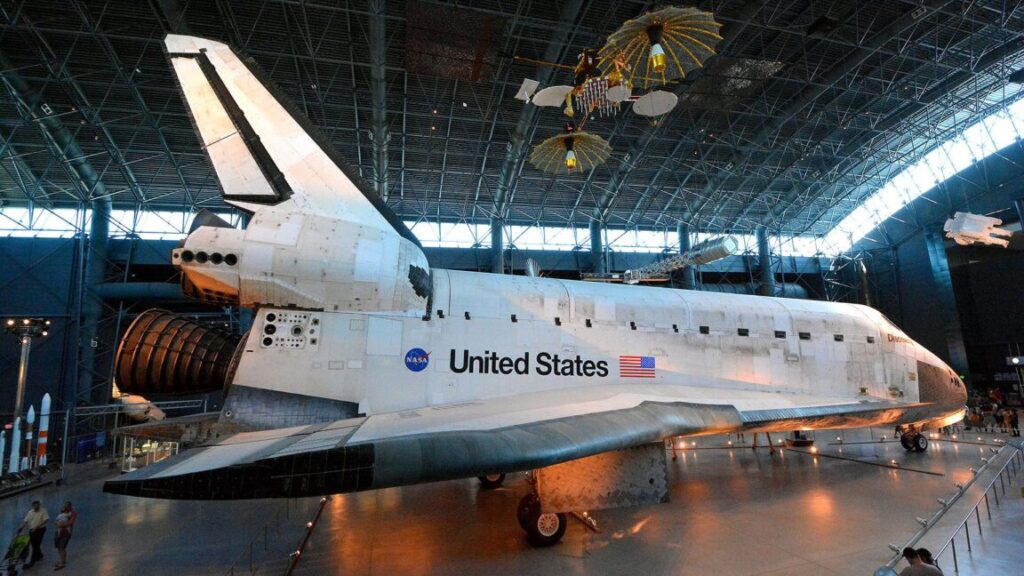

Lunar Outpost displayed its new Lego Technic Moon Rover Space Vehicle at Space Center Houston on August 2, 2025. Credit: collectSPACE.com

Similarly, Lego is a leader when it comes to inspiring the next generation as to what is possible.

“I bet most engineers started out as a kid playing with Lego,” said Gemer. “We’ve got lots of great work to do with Lego, because it’s one of those foundational, inspirational things for kids in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math]. Tying that to space exploration, which is another one of those things everyone can connect with, it’s just a really natural partnership.”

Which brings it all back to Ari and Aiden and the Moon Rover Space Vehicle set.

“We built the MAPP rover, and then the resource collection rover. We are working our way up to the big one,” said Gemer. “I just want them to enjoy building it.”

When you purchase through links in this article, collectSPACE may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Lunar Outpost celebrates release of Lego Moon Rover Space Vehicle Read More »