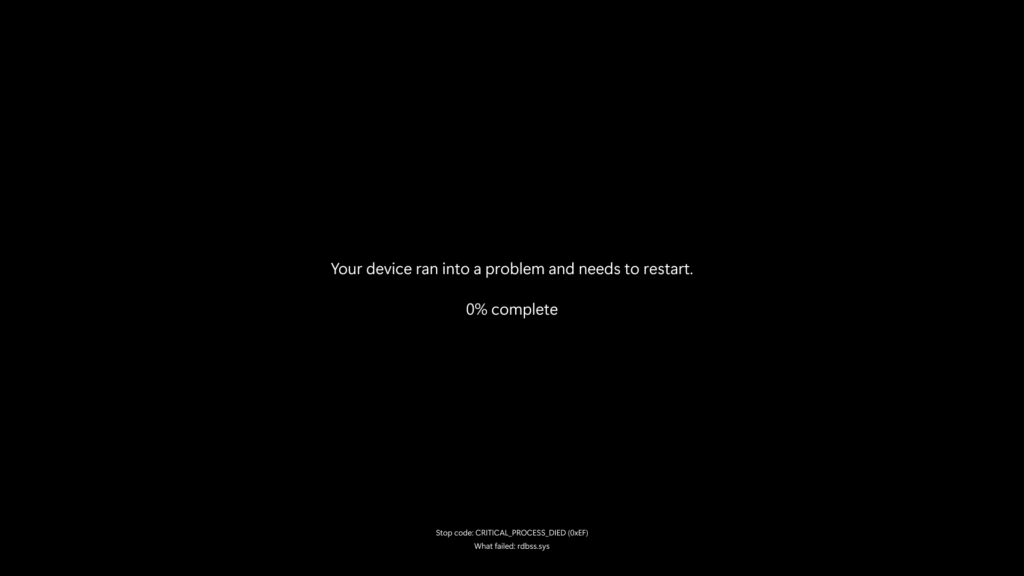

New Windows 11 build adds self-healing “quick machine recovery” feature

Preview build 27898 also includes a features that will shrink Taskbar items if you’ve got too many pins or running apps for everything to fit at once, changes the pop-up that apps use to ask for access to things like the system webcam or microphone, and allows you to add words to the dictionary used for the speech-to-text voice access features, among a handful of other changes.

It’s hard to predict when any given Windows Insider feature will roll out to the regular non-preview versions of Windows, but we’re likely just a few months out from the launch of Windows 11 25H2, this year’s “annual feature update.” Some of these updates, like last year’s 24H2, are fairly major overhauls that make lots of under-the-hood changes. Others, like 2023’s 23H2, mostly exist to change the version number and reset Microsoft’s security update clock, as each yearly update is only promised new security updates for two years after release.

The 25H2 update looks like one of the relatively minor ones. Microsoft says that the two versions “use a shared servicing branch,” and that 25H2 features will be “staged” on PCs running Windows 11 24H2, meaning that the code will be installed on systems via Windows Update but that they’ll be disabled initially. Installing the 25H2 “update” when it’s available will merely enable features that were installed but dormant.

New Windows 11 build adds self-healing “quick machine recovery” feature Read More »