Critical vulnerability affecting most Linux distros allows for bootkits

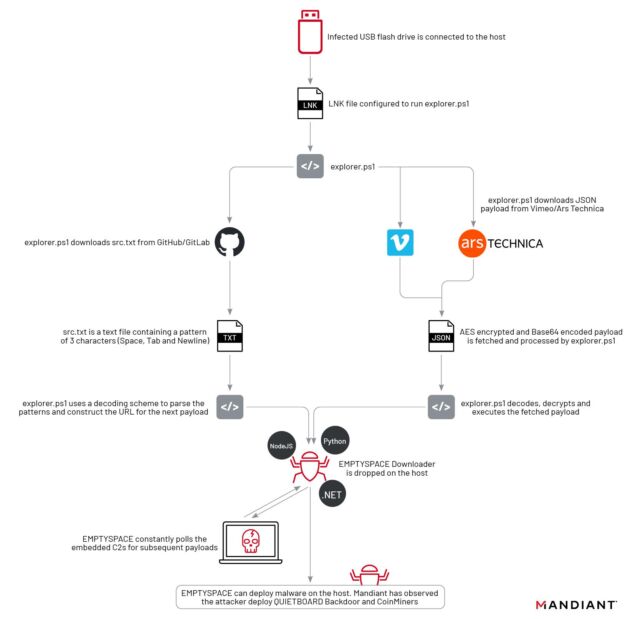

Linux developers are in the process of patching a high-severity vulnerability that, in certain cases, allows the installation of malware that runs at the firmware level, giving infections access to the deepest parts of a device where they’re hard to detect or remove.

The vulnerability resides in shim, which in the context of Linux is a small component that runs in the firmware early in the boot process before the operating system has started. More specifically, the shim accompanying virtually all Linux distributions plays a crucial role in secure boot, a protection built into most modern computing devices to ensure every link in the boot process comes from a verified, trusted supplier. Successful exploitation of the vulnerability allows attackers to neutralize this mechanism by executing malicious firmware at the earliest stages of the boot process before the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface firmware has loaded and handed off control to the operating system.

The vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2023-40547, is what’s known as a buffer overflow, a coding bug that allows attackers to execute code of their choice. It resides in a part of the shim that processes booting up from a central server on a network using the same HTTP that the Internet is based on. Attackers can exploit the code-execution vulnerability in various scenarios, virtually all following some form of successful compromise of either the targeted device or the server or network the device boots from.

“An attacker would need to be able to coerce a system into booting from HTTP if it’s not already doing so, and either be in a position to run the HTTP server in question or MITM traffic to it,” Matthew Garrett, a security developer and one of the original shim authors, wrote in an online interview. “An attacker (physically present or who has already compromised root on the system) could use this to subvert secure boot (add a new boot entry to a server they control, compromise shim, execute arbitrary code).”

Stated differently, these scenarios include:

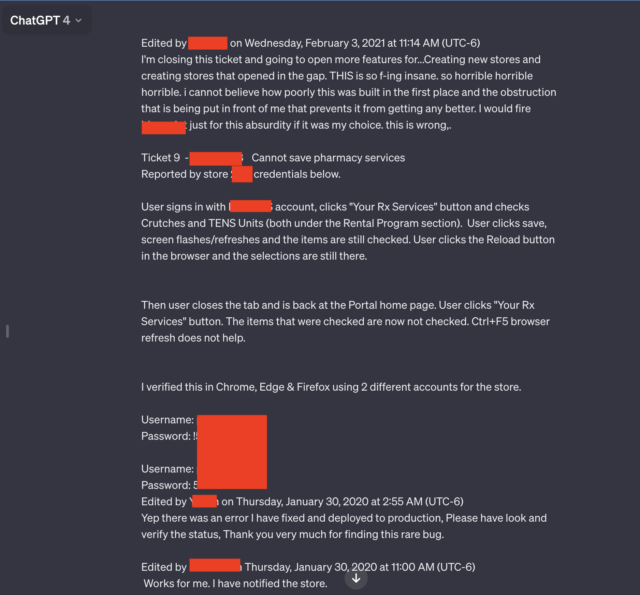

- Acquiring the ability to compromise a server or perform an adversary-in-the-middle impersonation of it to target a device that’s already configured to boot using HTTP

- Already having physical access to a device or gaining administrative control by exploiting a separate vulnerability.

While these hurdles are steep, they’re by no means impossible, particularly the ability to compromise or impersonate a server that communicates with devices over HTTP, which is unencrypted and requires no authentication. These particular scenarios could prove useful if an attacker has already gained some level of access inside a network and is looking to take control of connected end-user devices. These scenarios, however, are largely remedied if servers use HTTPS, the variant of HTTP that requires a server to authenticate itself. In that case, the attacker would first have to forge the digital certificate the server uses to prove it’s authorized to provide boot firmware to devices.

The ability to gain physical access to a device is also difficult and is widely regarded as grounds for considering it to be already compromised. And, of course, already obtaining administrative control through exploiting a separate vulnerability in the operating system is hard and allows attackers to achieve all kinds of malicious objectives.

Critical vulnerability affecting most Linux distros allows for bootkits Read More »