NASA has to be trolling with the latest cost estimate of its SLS launch tower

The plague lives on —

“NASA officials informed us they do not intend to request a fixed-price proposal.”

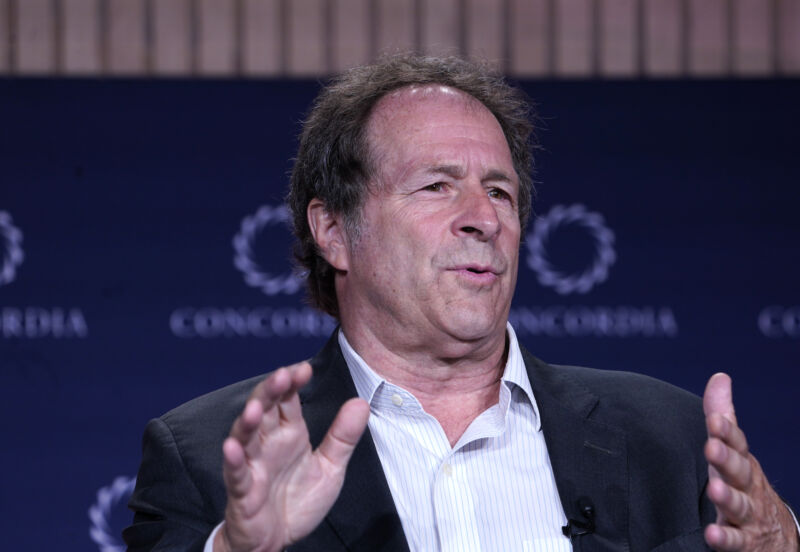

Enlarge / Teams with NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems Program and primary contractor Bechtel National, Inc. continue construction on the base of the platform for the new mobile launcher at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, April 24, 2024.

NASA/Isaac Watson

NASA’s problems with the mobile launch tower that will support a larger version of its Space Launch System rocket are getting worse rather than better.

According to a new report from NASA’s inspector general, the estimated cost of the tower, which is a little bit taller than the length of a US football field with its end zones, is now $2.7 billion. Such a cost is nearly twice the funding it took to build the largest structure in the world, the Burj Khalifa, which is seven times taller.

This is a remarkable explosion in costs as, only five years ago, NASA awarded a contract to the Bechtel engineering firm to build and deliver a second mobile launcher (ML-2) for $383 million, with a due date of March 2023. That deadline came and went with Bechtel barely beginning to cut metal.

According to NASA’s own estimate, the project cost for the tower is now $1.8 billion, with a delivery date of September 2027. However the new report, published Monday, concludes that NASA’s estimate is probably too conservative. “Our analysis indicates costs could be even higher due in part to the significant amount of construction work that remains,” states the report, signed by Deputy Inspector General George A. Scott.

Bigger rocket, bigger tower

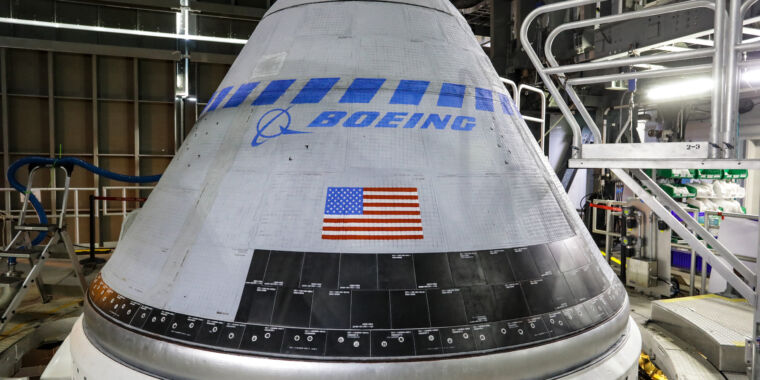

NASA commissioned construction of the launch tower—at the express direction of the US Congress—to support a larger version of the Space Launch System rocket known as Block 1B. This combines the rocket’s existing core stage with a larger and more powerful second stage, known as the Exploration Upper Stage, under development by Boeing.

The space agency expects to use this larger version of the SLS rocket beginning with the Artemis IV mission, which is intended to deliver both a crewed Orion spacecraft as well as an element of the Lunar Gateway into orbit around the Moon. This is to be the second time that astronauts land on the lunar surface as part of the Artemis Program. The Artemis IV mission has a nominal launch date of 2028, but the new report confirms the widely held assumption in the space community that such a date is unfeasible.

To make a 2028 launch date for this mission, NASA said it needs to have the ML-2 tower completed by November 2026. Both NASA and the new report agree that there is a zero percent chance of this happening. Accordingly, if the Artemis IV mission uses the upgraded version of the SLS rocket, it almost certainly will not launch until mid-2029 at the earliest.

Why have the costs and delays grown so much? One reason the report cites is Bechtel’s continual underestimation of the scope and complexity of the project.

“Bechtel vastly underestimated the number of labor hours required to complete the ML-2 project and, as a result, has incurred more labor hours than anticipated. From May 2022 to January 2024, estimated overtime hours doubled to nearly 850,000 hours, reflecting the company’s attempts to meet NASA’s schedule goals.

Difficult to hold Bechtel to account

One of the major takeaways from the new report is that NASA appears to be pretty limited in what it can do to motivate Bechtel to build the mobile launch tower more quickly or at a more reasonable price. The cost-plus contracting mechanism gives the space agency limited leverage over the contractor beyond withholding award fees. The report notes that NASA has declined to exercise an option to convert the contract to a fixed-price mechanism.

“While the option officially remains in the contract, NASA officials informed us they do not intend to request a fixed-price proposal from Bechtel,” the report states. “(Exploration Ground Systems) Program and ML-2 project management told us they presume Bechtel would likely provide a cost proposal far beyond NASA’s budgetary capacity to account for the additional risk that comes with a fixed-price contract.”

In other words, since NASA did not initially require a fixed price contract, it now sounds like any bid from Bechtel would completely blow a hole in the agency’s annual budget.

The spiraling costs of the mobile launch tower have previously been a source of frustration for NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. In 2022, after cost estimates for the ML-2 structure neared $1 billion, Nelson lashed out at the cost-plus mechanism during testimony to the US Congress.

“I believe that that is the plan that can bring us all the value of competition,” Nelson said of fixed-price contracts. “You get it done with that competitive spirit. You get it done cheaper, and that allows us to move away from what has been a plague on us in the past, which is a cost-plus contract, and move to an existing contractual price.”

The plague continues to spread.

NASA has to be trolling with the latest cost estimate of its SLS launch tower Read More »