LLMs’ impact on science: Booming publications, stagnating quality

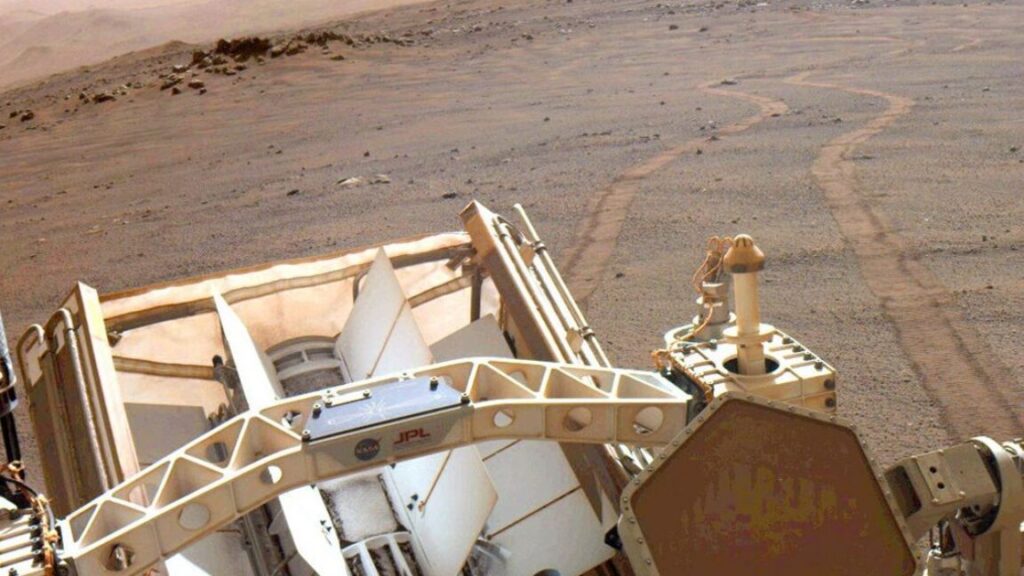

This effect was likely to be most pronounced in people that weren’t native speakers of English. If the researchers limited the analysis to people with Asian names working at institutions in Asia, their rate of submissions to bioRxiv and SSRN nearly doubled once they started using AI and rose by over 40 percent at the arXiv. This suggests that people who may not have the strongest English skills are using LLMs to overcome a major bottleneck: producing compelling text.

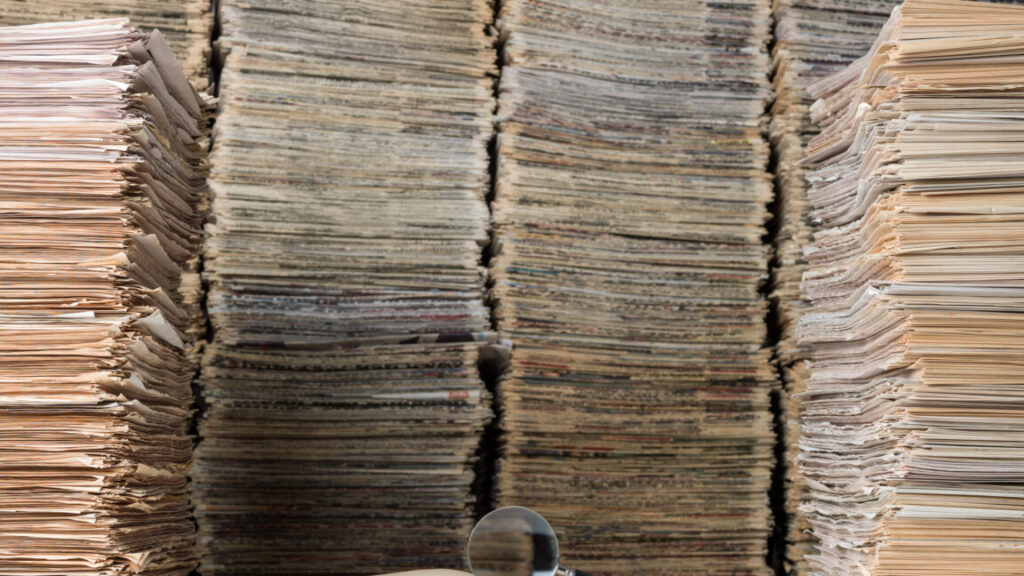

Quantity vs. quality

The value of producing compelling text should not be underestimated. “Papers with clear but complex language are perceived to be stronger and are cited more frequently,” the researchers note, suggesting that we may use the quality of writing as a proxy for the quality of the research it’s describing. And they found some indication of that here, as non-LLM-assisted papers were more likely to be published in the peer reviewed literature if they used complex language (the abstracts were scored for language complexity using a couple of standard measures).

But the dynamic was completely different for LLM-produced papers. The complexity of language in papers written with an LLM was generally higher than for those using natural language. But they were less likely to end up being published. “For LLM-assisted manuscripts,” the researchers write, “the positive correlation between linguistic complexity and scientific merit not only disappears, it inverts.”

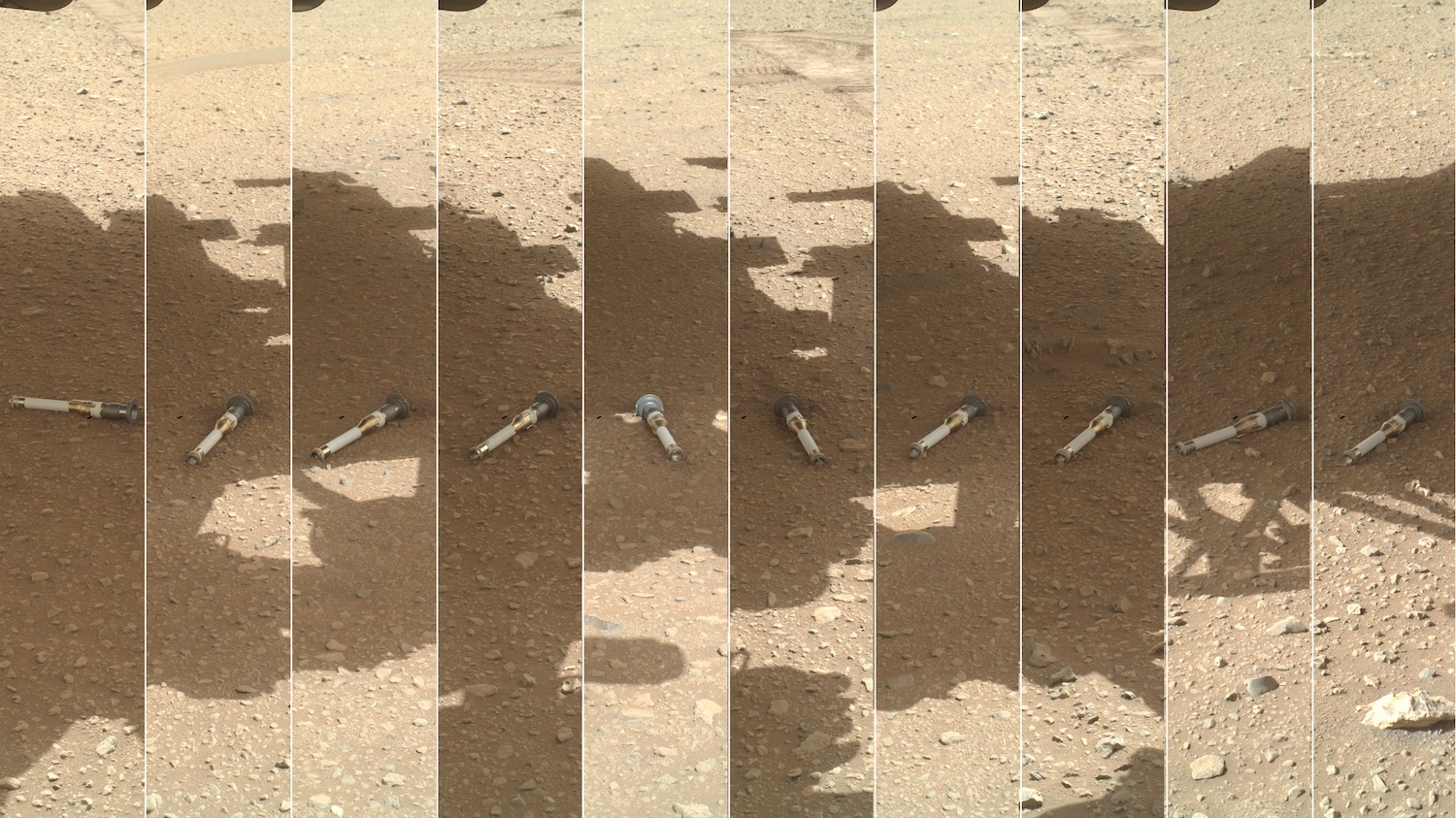

But not all of the differences were bleak. When the researchers checked the references being used in AI-assisted papers, they found that the LLMs weren’t just citing the same papers that everyone else did. They instead cited a broader range of sources, and were more likely to cite books and recent papers. So, there’s a chance that AI use could ultimately diversify the published research that other researchers consider (assuming they check their own references, which they clearly should).

What does this tell us?

There are a couple of cautions for interpreting these results. One, acknowledged by the researchers, is that people may be using AI to produce initial text that’s then heavily edited, and that may be mislabeled as human-produced text here. So, the overall prevalence of AI use is likely to be higher. The other is that some manuscripts may take a while to get published, so their use of that as a standard for scientific quality may penalize more recent drafts—which are more likely to involve AI use. These may ultimately bias some of the results, but the effects the authors saw were so large that they’re unlikely to go away entirely.

LLMs’ impact on science: Booming publications, stagnating quality Read More »