Maker of weight-loss drugs to ask Trump to pause price negotiations: Report

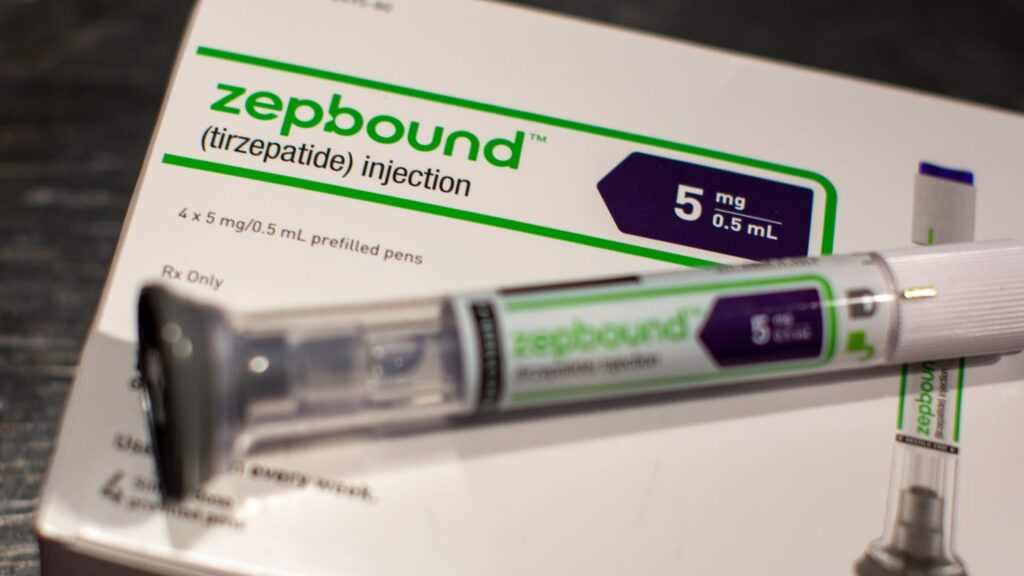

Popular prescriptions

For now, Medicare does not cover drugs prescribed specifically for weight loss, but it will cover GLP-1 class drugs if they’re prescribed for other conditions, such as Type 2 diabetes. Wegovy, for example, is covered if it is prescribed to reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke in adults with either obesity or overweight. But, in November, the Biden administration proposed reinterpreting Medicare prescription-coverage rules to allow for coverage of “anti-obesity medications.”

Such a move is reportedly part of the argument Lilly’s CEO plans to bring to the Trump administration. Rather than using drug price negotiations to reduce health care costs, Ricks aims to play up the potential to reduce long-term health care costs by improving people’s overall health with coverage of GLP-1 drugs now. This argument would presumably be targeted at Mehmet Oz, the TV presenter and heart surgeon Trump has tapped to run the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

“My argument to Mehmet Oz is that if you want to protect Medicare costs in 10 years, have [the Affordable Care Act] and Medicare plans list these drugs now,” Ricks said to Bloomberg. “We know so much about how much cost savings there will be downstream in heart disease and other conditions.”

An October report from the Congressional Budget Office strongly disputed that claim, however. The CBO estimated that the direct cost of Medicare coverage for anti-obesity drugs between 2026 and 2034 would be nearly $39 billion, while the savings from improved health would total just a little over $3 billion, for a net cost to US taxpayers of about $35.5 billion.

Maker of weight-loss drugs to ask Trump to pause price negotiations: Report Read More »