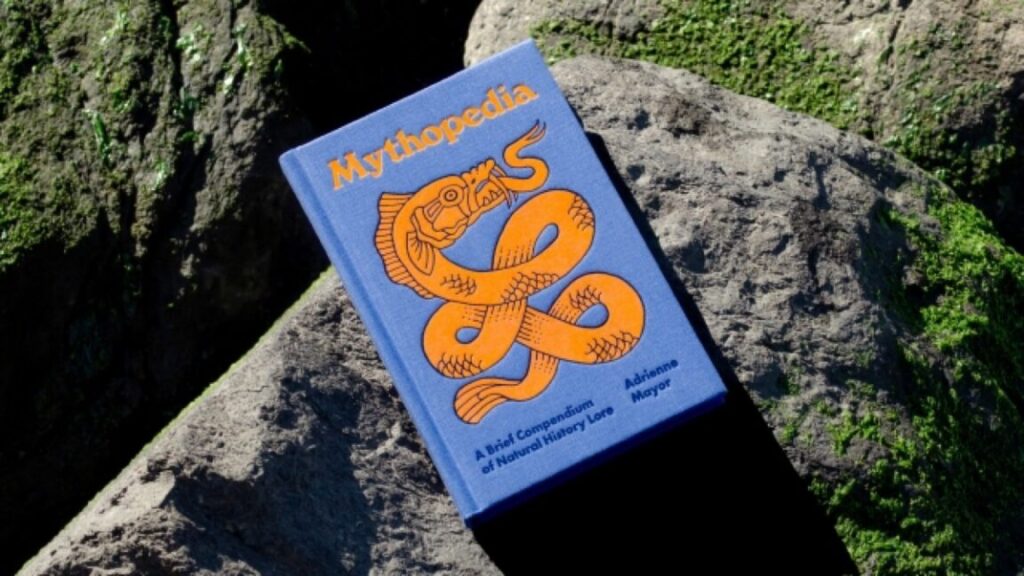

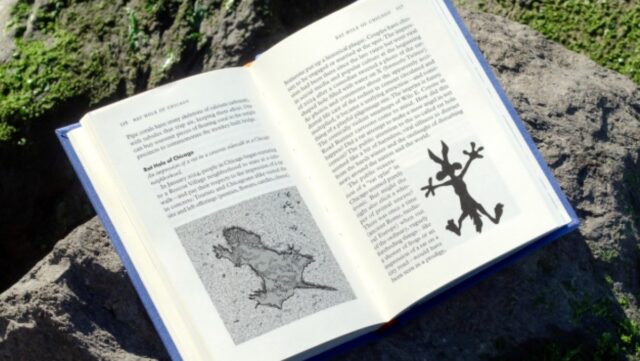

A quirky guide to myths and lore based in actual science

Folklorist/historian Adrienne Mayor on her new book Mythopedia: A Brief Compendium of Natural History Lore

Credit: Princeton University Press

Earthquakes, volcanic eruption, eclipses, meteor showers, and many other natural phenomena have always been part of life on Earth. In ancient cultures that predated science, such events were often memorialized in myths and legends. There is a growing body of research that strives to connect those ancient stories with the real natural events that inspired them. Folklorist and historian Adrienne Mayor has put together a fascinating short compendium of such insights with Mythopedia: A Brief Compendium of Natural History Lore, from dry quicksand and rains of frogs to burning lakes, paleoburrows, and Scandinavian “endless winters.”

Mayor’s work has long straddled multiple disciplines, but one of her specialities is best described as geomythology, a term coined in 1968 by Indiana University geologist Dorothy Vitaliano, who was interested in classical legends about Atlantis and other civilizations that were lost due to natural disasters. Her interest resulted in Vitaliano’s 1973 book Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins.

Mayor herself became interested in the field when she came across Greek and Roman descriptions of fossils, and that interest expanded over the years to incorporate other examples of “folk science” in cultures around the world. Her books include The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy (2009), as well as Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & the Scorpion Bombs (2022), exploring the origins of biological and chemical warfare. Her 2018 book, Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology, explored ancient myths and folklore about creating automation, artificial life, and AI, connecting them to the robots and other ingenious mechanical devices actually designed and built during that era.

When her editor at Princeton University Press approached her about writing a book on geomythology, she opted for an encyclopedia format, which fit perfectly into an existing Princeton series of little encyclopedias about nature. “In this case, I wasn’t going to be working with just Greek and Roman antiquity,” Mayor told Ars. “I had collected very rich files on geomyths around the world. There are even a few modern geomyths in there. You can dip into whatever you’re interested in and skip the rest. Or maybe later you’ll read the ones that didn’t seem like they would be of interest to you but they’re absolutely fascinating.”

Mythopedia is also a true family affair, in that illustrator Michelle Angel is Mayor’s sister. “She does figures and maps for a lot of scholarly books, including mine,” said Mayor. “She’s very talented at making whimsical illustrations that are also very scientifically accurate. She really added information not only to the essays but to the illustrations for Mythopedia.

As she said, Mayor even includes a few modern geomyths in her compendium, as well as imagining in her preface what kind of geomyths might be told thousands of years from today about the origins of climate change for example, or the connection between earthquakes and fracking. “How will people try to explain the perplexing evidence that they’ll find on the planet Earth and maybe on other planets?” she said. “How will those stories be told?”

Ars caught up with Mayor to learn more.

Credit: Princeton University Press

Ars Technica: Tell us a little about the field of geomythology.

Adrienne Mayor: It’s a relatively new field of study but it took off around 2000. Really, it’s a storytelling that has existed since the first humans started talking to one another and investigating their landscape. I think geomyths are attempts to explain perplexing evidence in nature—on the Earth or in the sky. So geomyth is a bit of a misnomer since it can also cover celestial happenings. But people have been trying to explain bizarre things, or unnatural looking things, or inexplicable things in their landscape and their surroundings since they could first speak.

These kind of stories were probably first told around the first fires that human beings made as soon as they had language. So geomyths are attempts to explain, as I say, but they also contain memories that are preserved in oral traditions. These are cultures that are trying to understand earthshaking events like volcanoes or massive floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, avalanches—things that really change the landscape and have an impact on their culture. Geomyths are often expressed in metaphors and poetic, even supernatural language, and that’s why they’ve been ignored for a long time because people thought they were just storytelling or fiction.

But the ones that are about nature, about natural disasters, are based on very keen observations and repeated observations of the landscape. They also can contain details that are recognizable to scientists who study earthquakes or volcanoes. The scientists then realized that there had to be, in some cases, eyewitness accounts of these geomyths. Geomythology is actually enhancing our scientific understanding of the history of Earth over time. It can help people who study climate change figure out how far back certain climate changes have been happening. They can shed light on how and when great geological upheavals actually occurred and how humans responded to them.

Ars Technica: How long can an oral tradition about a natural disaster really persist?

Adrienne Mayor: That was one of the provocative questions. Can it really persist over centuries, thousands of years, millennia? For a long time people thought that oral traditions could not persist for that long. But it turns out that with detailed studies of geomyths that can be related to datable events like volcanoes or earthquakes or tsunamis from geophysical evidence, we now know that the myths can last thousands of years.

For instance, the one that is told by the Klamath Indians about the creation of Crater Lake in Oregon that happened about 7,000 years ago—the details in their myth show that there were eyewitness accounts. Archaeologists have found a particular kind of woven sandal that was used by indigenous peoples 9,000 to 5,000 years ago. They found those sandals both above and below the ash from the volcano that exploded. So we have two ways of dating that. In Australia, people who study the geomyths of the Aborigines can relate their stories to events that happened 20,000 years ago.

Ars Technica: You mentioned that your interest in geomythology grew out of Greek and Roman interpretations of certain fossils that they found.

Adrienne Mayor: That really did trigger it, because it occurred to me that oral traditions and legends—rather than myths about gods and heroes—the ones that are about nature seem to have kernels of truth because it could be reaffirmed and confirmed and supported by evidence that people see over generations. I was in Greece and saw some fossils that had been plowed up by farmers on the island of Samos, thigh-bones from a mastodon or a mammoth or a giant rhinoceros. The museum curator said, “Yes, farmers bring us these all the time.” And I thought, why hasn’t it occurred to anyone that they were doing this in antiquity as well?

I read through about 30 different Greek and Roman authors from the time of Homer up through Augustine, and found more than a hundred incidents of finding remarkable bones of strange shape, gigantic bones that were inexplicable. How did they try to explain them? That’s really what got me going. These stories had all been dismissed as travelers’ tales or superstition. But I talked with paleontologists and found that if I superimposed a map of all the Greek and Roman finds of remarkable remains of giants or monsters, it actually matched the paleontological map of deposits of megafauna—not dinosaurs, but megafauna like mastodons and mammoths.

Also, I grew up in South Dakota where there were a lot of fossils, so I had always wondered what Native Americans had thought about dinosaur fossils. It turns out no one had asked them either. So my second book was Fossil Legends of the First Americans. In that case, I knew the geography of all the deposits of dinosaur fossils. I just had to drive about 6,000 miles around to reservations, talking to storytellers and elders and ordinary people to try and excavate the folklore. So I sometimes would read a scientific report in the media and think, “here’s got to be oral traditions about this,” and then I find them. And sometimes I find the myth and seek the historical or scientific kernels embedded in it.

Ars Technica: What were your criteria for narrowing your list down to just 53 myths?

Adrienne Mayor: I had to do something for every letter; that was a challenge. A few other authors in the series actually skipped the hard letters. I started out with the hard letters like Q, W, X, Z, Y. My husband says I almost got mugged by the letter Q because I got so obsessed with quicksand. I started talking about writing a book about quicksand because I was so obsessed with sand. There are singing sand dunes.

Ars Technica: There’s been a lot of research on the physics of singing sand dunes.

Adrienne Mayor: Yes. Isn’t that amazing? There are even some humorous stories. One of my favorites is that Muslim pilgrims in the medieval period would travel to special singing sand dunes between Afghanistan and Iran. When pilgrims would feel the need to relieve themselves, they would try to find some privacy, yet urinating and defecating on the sand dune caused a very loud drum roll sound.

Ars Technica: Your work necessarily spans multiple disciplines in both the sciences and the humanities. Has that been a challenge?

Adrienne Mayor: I’ve built my career since my first book in 2000 on trying to write not only to other disciplines, but to ordinary educated readers. Some people think it feels like walking a tight rope, but not to me because I don’t have a canonical academic career. I’m an autodidact, I’m not really an academic. So I have absolutely no problem trespassing in all kinds of disciplines. And I depend on the generosity of all these experts.

Some are from the classics and humanities, but an awful lot of them are from scientific disciplines. I think there’s a big tendency to want to collaborate. It’s just that in academia it’s been difficult because people are siloed. So I feel like I have worked as a bridge between the two. Scientists seem very excited to find out that there are epic poems discussing exactly what they’re studying. Paleontologists were thrilled to discover that people were noticing fossils more than 2000 years ago. So the impulse and the desire to collaborate is there.

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

A quirky guide to myths and lore based in actual science Read More »