Neolithic people took gruesome trophies from invading tribes

A local Neolithic community in northeastern France may have clashed with foreign invaders, cutting off limbs as war trophies and otherwise brutalizing their prisoners of war, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances. The findings challenge conventional interpretations of prehistoric violence as bring indiscriminate or committed for pragmatic reasons.

Neolithic Europe was no stranger to collective violence of many forms, such as the odd execution and massacres of small communities, as well as armed conflicts. For instance, we recently reported on an analysis of human remains from 11 individuals recovered from El Mirador Cave in Spain, showing evidence of cannibalism—likely the result of a violent episode between competing Late Neolithic herding communities about 5,700 years ago. Microscopy analysis revealed telltale slice marks, scrape marks, and chop marks, as well as evidence of cremation, peeling, fractures, and human tooth marks.

This indicates the victims were skinned, the flesh removed, the bodies disarticulated, and then cooked and eaten. Isotope analysis indicated the individuals were local and were probably eaten over the course of just a few days. There have been similar Neolithic massacres in Germany and Spain, but the El Mirador remains provide evidence of a rare systematic consumption of victims.

Per the authors of this latest study, during the late Middle Neolithic, the Upper Rhine Valley was the likely site of both armed conflict and rapid cultural upheaval, as groups from the Paris Basin infiltrated the region between 4295 and 4165 BCE. In addition to fortifications and evidence of large aggregated settlements, many skeletal remains from this period show signs of violence.

Friends or foes?

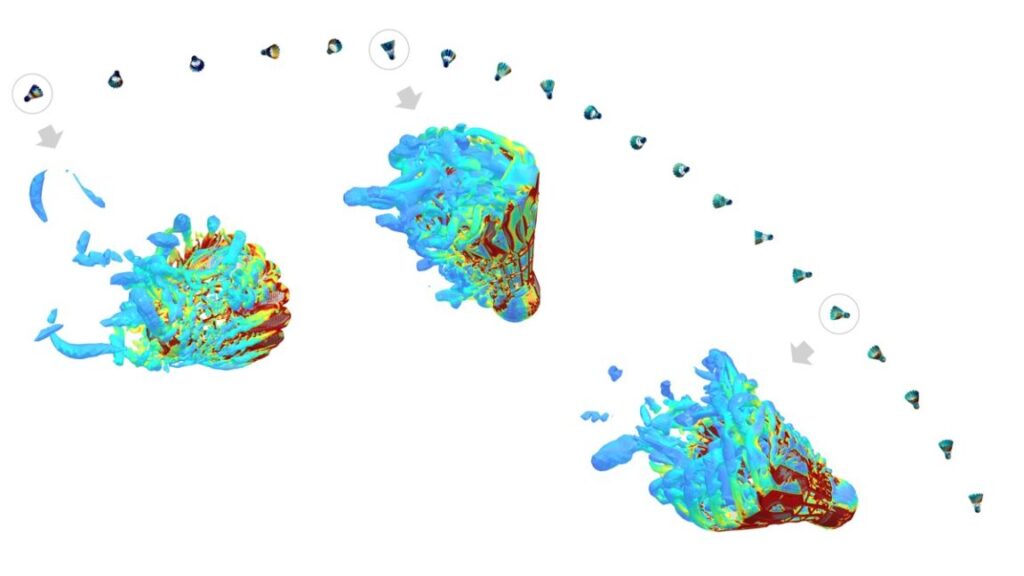

Overhead views of late Middle Neolithic violence-related human mass deposits in Pit 124 of the Alsace region, France. Credit: Philippe Lefranc, INRAP

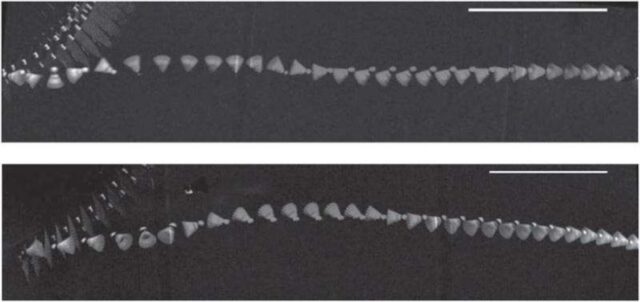

Archaeologist Teresa Fernandez-Crespo of Spain’s Valladolid University and co-authors focused their analysis on human remains excavated from two circular pits at the Achenheim and Bergheim sites in Alsace in northwestern France. Fernandez-Crespo et al. examined the bones and found that many of the remains showed signs of unhealed trauma—such as skull fractures—as well as the use of excessive violence (overkill), not to mention quite a few severed left upper limbs. Other skeletons did not show signs of trauma and appeared to have been given a traditional burial.

Neolithic people took gruesome trophies from invading tribes Read More »