Research roundup: 6 cool science stories we almost missed

Also: the science of regular vs. gluten-free spaghetti, catching high-speed snake bites in action, etc.

Karnak Temple, Luxor, Egypt. Credit: Ben Pennington

It’s a regrettable reality that there is never enough time to cover all the interesting scientific stories we come across each month. In the past, we’ve featured year-end roundups of cool science stories we (almost) missed. This year, we’re experimenting with a monthly collection. October’s list includes the microstructural differences between regular and gluten-free spaghetti, capturing striking snakes in action, the mystery behind the formation of Martian gullies, and—for all you word game enthusiasts—an intriguing computational proof of the highest possible scoring Boggle board.

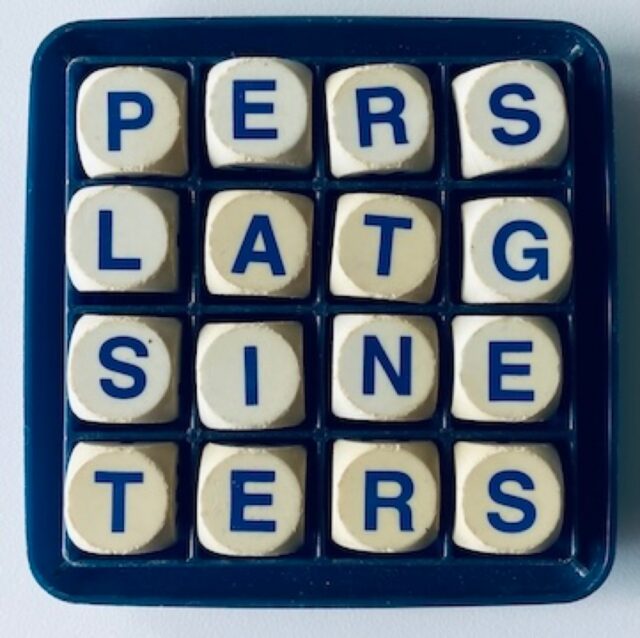

Highest-scoring Boggle board

Credit: Dan Vanderkam

Sometimes we get handy story tips from readers about quirkily interesting research projects. Sometimes those projects involve classic games like Boggle, in which players find as many words as they can from a 4×4 grid of 16 lettered cubic dice, within a given time limit. Software engineer Dan Vanderkam alerted us to a a preprint he posted to the physics arXiv, detailing his quest to find the Boggle board configuration that yields the highest possible score. It’s pictured above, with a total score of 3,625 points, according to Vanderkam’s first-ever computational proof. There are more than 1000 possible words, with “replastering” being the longest.

Vanderkam has documented his quest and its resolution (including the code he used) extensively on his blog, admitting to the Financial Times that, “As far as I can tell, I’m the only person who is actually interested in this problem.” That’s not entirely true: there was an attempt in 1982 that found an optimal board yielding 2,195 points. Vanderkam’s board was known as possibly being the highest scoring, it was just very difficult to prove using standard heuristic search methods. Vanderkam’s solution involved grouping board configurations with similar patterns into classes, and then finding upper bounds to discard clear losers, rather than trying to tally scores for each board individually—i.e., an old school “branch and bound” technique.

DOI: arXiv, 2025. 10.48550/arXiv.2507.02117 (About DOIs).

Origins of Egypt’s Karnak Temple

Credit: Ben Pennington

Egypt’s Karnak Temple complex, located about 500 meters of the Nile River near Luxor, has long been of interest to archaeologists and millions of annual tourists alike. But its actual age has been a matter of much debate. The most comprehensive geological survey conducted to date is yielding fresh insights into the temple’s origins and evolution over time, according to a paper published in the journal Antiquity.

The authors analyzed sediment cores and thousands of ceramic fragments from within and around the site to map out how the surrounding landscape has changed. They concluded that early on, circa 2520 BCE, the site would have experienced regular flooding from the Nile; thus, the earliest permanent settlement at Karnak would have emerged between 2591 and 2152 BCE, in keeping with the earliest dated ceramic fragments. This would have been after river channels essentially created an island of higher ground that served as the foundation for constructing the temple. As those channels diverged over millennia, the available area for the temple expanded and thus, so did the complex.

This might be supported by Egyptian creation myths. “It’s tempting to suggest the Theban elites chose Karnak’s location for the dwelling place of a new form of the creator god, ‘Ra-Amun,’ as it fitted the cosmogonical scene of high ground emerging from surrounding water,” said co-author Ben Pennington, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Southampton. “Later texts of the Middle Kingdom (c.1980–1760 BC) develop this idea, with the ‘primeval mound’ rising from the ‘Waters of Chaos.’ During this period, the abating of the annual flood would have echoed this scene, with the mound on which Karnak was built appearing to ‘rise’ and grow from the receding floodwaters.”

DOI: Antiquity, 2025. 10.15184/aqy.2025.10185 (About DOIs).

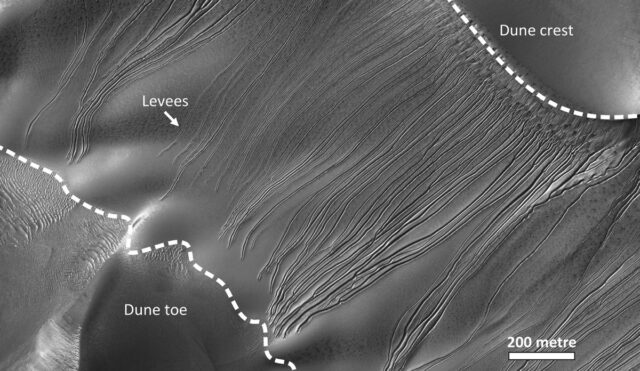

Gullies on Mars

Credit: HiRISE/NASA/JPL/University of Arizon

Mars has many intriguing features but one of the more puzzling is the sinuous gullies that form on some its dunes. Scientists have proposed two hypotheses for how such gullies might form. The first is that they are the result of debris flow from an earlier time in the planet’s history where liquid water might have existed on the surface—evidence that the red planet might once have been habitable. The second is that the gullies form because of seasonal deposition and sublimation of CO2 ice on the surface in the present day. A paper published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters demonstrated strong evidence in favor of the latter hypothesis.

Building on her earlier research on how sublimation of CO2 ice can drive debris flows on Mars, earth scientist Lonneke Roelofs of Utrecht University in the Netherlands collaborated with scientists at the Open University in Milton Keynes, UK, which boasts a facility for simulating conditions on Mars. She ran several experiments with different sediment types, creating dune slopes of different angles and dropping blocks of CO2 ice from the top of the slope. At just the right angle, the blocks did indeed start digging into the sandy slope and moving downwards to create a gully. Roelofs likened the effect to a burrowing mole or the sandworms in Dune.

Per Roelofs, on Mars, CO2 ice forms over the surface during the winter and starts to sublimate in the spring. The ice blocks are remnants found on the shaded side of dune tops, where they break off once the temperature gets high enough and slide down the slope. At the bottom, they keep sublimating until all the CO2 has evaporated, leaving behind a hollow of sand.

DOI: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025. 10.1029/2024GL112860 (About DOIs).

Snake bites in action

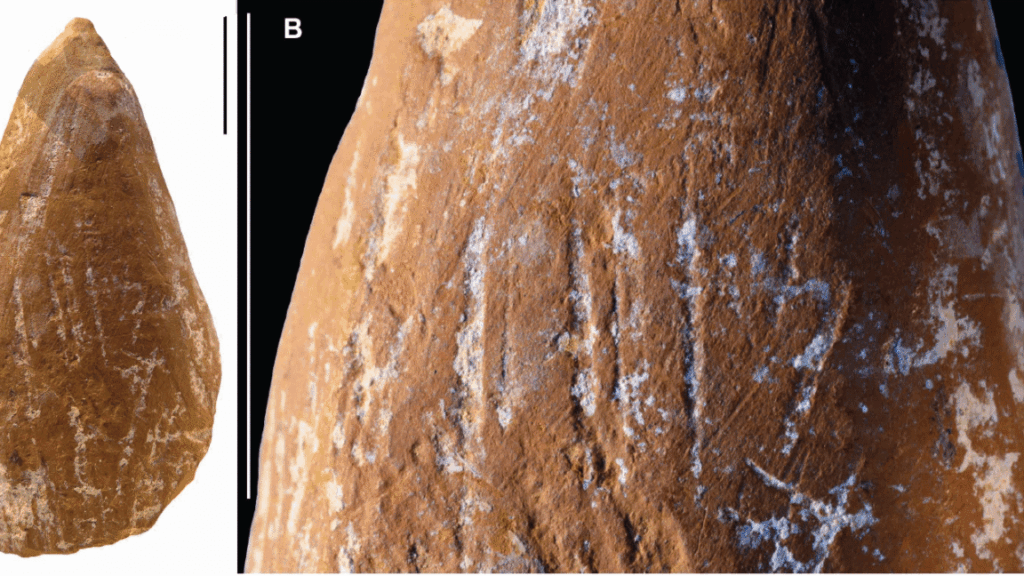

S.G.C. Cleuren et al., 2025

Snakes can strike out and bite into prey in as little as 60 microseconds and until quite recently it just wasn’t technologically possible to capture those strikes in high definition. Researchers at Monash University in Australia decided to test 36 different species of snake in this way to learn more about their unique biting styles, detailing their results in a paper published in the Journal of Experimental Biology. And oh yes, there is awesome video footage.

Alistair Evans and Silke Cleuren traveled to Venomworld in Paris, France, where snake venom is harvested for medical and pharmaceutical applications. For each snake species, they poked at said snake with a cylindrical piece of warm medical gel to mimic meaty muscle until the snake lunged and buried its fangs into the gel. Two cameras recorded the action at 1000 frames per second, capturing more than 100 individual strikes in great detail.

Among their findings: vipers moved the fastest when they struck, with the blunt-nosed viper accelerating up to 710 m/s2, landing a bite within 22 microseconds. All the vipers landed bites within 100 microseconds of striking. By contrast, the rough-scaled death adder only reached speeds of 2.5 m/s2. Vipers also sometimes pulled out and reinserted their fangs if they didn’t like the resulting angle; only then did they inject their venom. Elapids like the Cape coral cobra bit their prey repeatedly to inject their venom, while colubrids would tear gashes into their prey by sweeping their jaws from side to side, ensuing the maximum possible amount of venom was delivered.

DOI: Journal of Experimental Biology, 2025. 10.1242/jeb.250347 (About DOIs).

Spaghetti secrets

Spaghetti, like most pasta, is made of semolina flour, which is mixed with water to form a paste and then extruded to create a desired shape. The commercial products are then dried—an active area of research, since it’s easy for the strands to crack during the process. In fact, there have been a surprisingly large number of scientific papers seeking to understand the various properties of spaghetti, both cooking and eating it—the mechanics of slurping the pasta into one’s mouth, for instance, or spitting it out (aka, the “reverse spaghetti problem”); how to tell when it’s perfectly al dente; and how to get dry spaghetti strands to break neatly in two, rather than three or more scattered pieces.

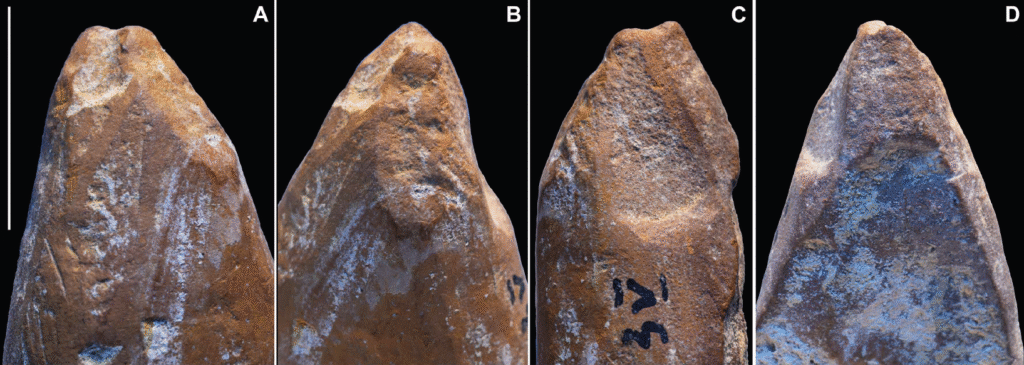

Pasta also has a fairly low glycemic index, and is thus a good option for those with heart disease or type 2 diabetes. With the rise in the number of people with a gluten intolerance, gluten-free spaghetti has emerged as an alternative. The downside is that gluten-free pasta is harder to cook correctly and decidedly subpar in taste and texture (mouthfeel) compared to regular pasta. The reason for the latter lies in the microstructure, according to a paper published in the journal Food Hydrocolloids.

The authors used small-angle x-ray scattering and small-angle neutron scattering to analyze the microstructure of both regular and gluten-free pasta—i.e., the gluten matrix and its artificial counterpart—cooked al dente with varying salt concentrations in the water. They found that because of its gluten matrix, regular pasta has better resistance to structural degradation, and that adding just the right amount of salt further reinforces that matrix—so it’s not just a matter of salting to taste. This could lead to a better alternative matrix for gluten-free pasta that holds its structure better and has a taste and mouthfeel closer to that of regular pasta.

DOI: Food Hydrocolloids, 2025. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.111855 (About DOIs).

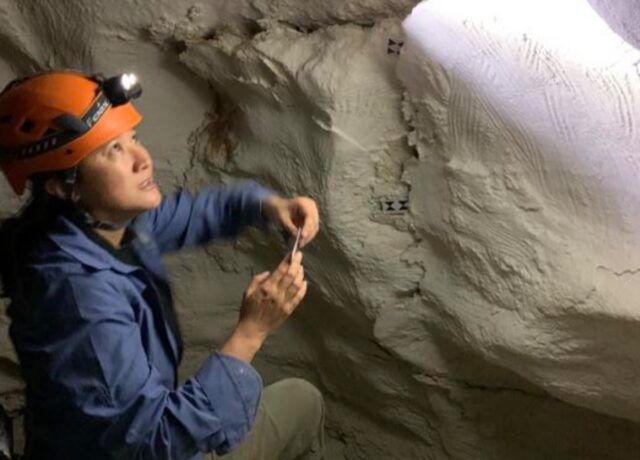

Can machine learning identify ancient artists?

Credit: Andrea Jalandoni

Finger flutings are one of the oldest examples of prehistoric art, usually found carved into the walls of caves in southern Australia, New Guinea, and parts of Europe. They’re basically just marks made by human fingers drawn through the “moonmilk” (a soft mineral film) covering those walls. Very little is known about the people who left those flutings and while some have tried to draw inferences based on biometric finger ratios or hand size measurements—notably whether given marks were made by men or women—such methods produce inconsistent results and are prone to human error and bias.

That’s why digital archaeologist Andrea Jaladonia of Griffith University decided to experiment with machine learning image recognition methods as a possible tool, detailing her findings in a paper published the journal Scientific Reports. She recruited 96 adult volunteers to create their own finger flutings in two different settings: once in a virtual reality environment, and once on a substitute for the moonmilk clay that mimicked the look and feel of the real thing. Her team took images of those flutings and then used them to train two common image recognition models.

The results were decidedly mixed. The virtual reality images performed the worst, yielding highly unreliable attempts at classifying whether flutings were made by men or women. The images produced in actual clay produced better results, even reaching close to 84 percent accuracy in one model. But there were also signs the models were overfitting, i.e., memorizing patterns in the training data rather than more generalized patterns, so the approach needs more refinement before it is ready for actual deployment. As for why determining sex classifications matters, “This information has been used to decide who can access certain sites for cultural reasons,” Jalandoni explained.

DOI: Scientific Reports, 2025. 10.1038/s41598-025-18098-4 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Research roundup: 6 cool science stories we almost missed Read More »