Centuries before the Inca, Peru’s wealthy imported parrots from afar

The Inca Empire’s system of roads were built on centuries-old trade routes.

This large, elaborate Ychsma funerary bundle features a wooden mask painted with cinnabar and adorned with a parrot-feather headdress. Credit: Olah et al. 2026

Centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire, a much smaller kingdom on the central coast of Peru already had a sophisticated trade network—one it used to import live parrots across the Andes from the Amazon rainforest.

Australian National University conservation geneticist George Olah and his colleagues recently studied feathers from a headdress in a Ychsman noble’s tomb, dating to 1100–1400 CE (the centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire). DNA and chemical isotopes reveal that the parrots the feathers came from (still bright blue, yellow, and green after all these centuries) were born in the wild on the far side of the Andes but kept in captivity somewhere on the Peruvian coast. To pull off importing live parrots from hundreds of miles away across the steep, towering Andes, the Ychsma (who the Inca annexed around 1470) must have had a far-reaching trade network that spanned at least half a continent.

And they must have really liked birds.

Long-distance trade before the Inca roads

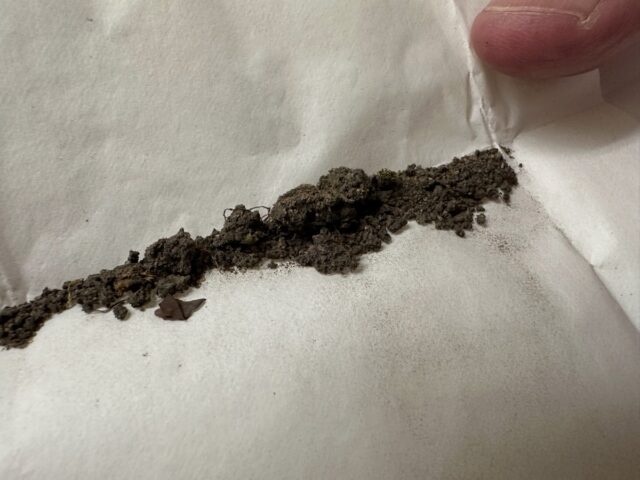

Olah and his colleagues carefully selected fragments of individual barbs (the thin keratin strands that make up the body of a feather) from 25 feathers sewn onto funerary headdresses found at the pre-Inca city of Pachacamac, located on the dry coast of present-day Peru, just south of Lima. From each fragment, researchers sequenced mitochondrial DNA and measured the ratios of certain nitrogen and carbon isotopes, which can reveal information about a creature’s diet.

The results suggest the parrots were born in the wild but spent at least a year in captivity eating local maize. That means they must have been captured hundreds of kilometers away, because parrots don’t tend to flock to the desert on their own.

The Ychsma kingdom grew out of a fragment of the old Wari Empire (known for its hallucinogenic beer, its canal system, and for breaking up around 1100 CE after a solid 500-year run). Centered at Pachacamac, the Ychsma built pyramids and irrigated their arid river valleys to grow crops. And like most of the cultures that lived in the Andes highlands and along the coasts of modern-day Peru and Chile, they really had a thing for parrot feathers.

Parrots’ colorful blue, green, and red feathers were the status symbol, “essential for communicating status, power, and cosmology,” as Olah and his colleagues put it. In the Andes highlands, the Wari—and later the Inca—imported bright-feathered rainforest birds in the millions over several centuries. On the coasts, the Moche and Nasca cultures did much the same.

Parrot feathers feature in headdresses and in tunics made from thousands of feathers sewn onto cotton cloth. The birds themselves show up in tombs and temples as mummified offerings, and they were sculpted and painted onto centuries’ worth of pottery.

The parrot feathers on a handful of funerary headdresses from one of the only unlooted, intact tombs left at Pachacamac recently indicated that the Ychsma were linked to a trade network that once connected huge swaths of two continents across hundreds of kilometers.

Based on parrots and their feathers alone, archaeologists knew there must have been connections that reached from the Amazon basin west to the coastal deserts of Chile and Peru and north to Mexico and the southwestern United States. But the details of that trade—including how live parrots ended up crossing one of the world’s most daunting mountain ranges—were unclear for the centuries before the rise of the Inca Empire and its imperial road networks.

Until recently, archaeologists and historians assumed that the period between the breakup of the Wari Empire and the rise of the Inca was mostly a time when smaller kingdoms and confederations, like Ychsma and its neighbors, squabbled with each other and had influence that didn’t reach much beyond their own region. But based on parrot feathers, these between-empires Andean cultures actually had complex, thriving, and very sophisticated trade relationships without needing to have a system imposed by a central imperial government.

Macaws hang out in the Peruvian Amazon. Credit: Balazs Tisza

Born in the rainforest, raised in the desert

The headdress feathers came from four parrot species: scarlet macaws, red-and-green macaws, blue-and-yellow macaws, and mealy amazons. (The last are cute little green dudes that really deserve a nicer name; “mealy” is apparently a reference to the dusty “powder down,” grains of keratin formed by the disintegrating tips of their down feathers.) All of them live in lowland tropical forests and palm swamps in the Amazon Basin; Peru’s coastal deserts are practically the opposite of their usual wet, lush habitat.

Some pre-colonization cultures bred their own parrots, including at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico and at a huge pueblo complex called Paquimé in Mexico’s Chihuahua Desert. You can tell from the Paquimé parrots’ DNA that they came from a small, slightly inbred population, probably one descended from a breeding colony imported together on a single trip.

But at Pachacamac, the parrots’ DNA looked like it had come from a larger, more genetically diverse population. In fact, it looked a lot like the level of genetic diversity found in modern wild parrots. In other words, the Pachacamac headdresses used feathers from parrots born and bred in the wild.

But they didn’t spend their entire lives there. “The birds were not living in the rainforest when these feathers grew,” wrote Olah and his colleagues. A high proportion of carbon-13 in the feather barbs meant that while they were growing, the birds had been eating a diet rich in domestic grains like maize. Meanwhile, nitrogen-15 in the feathers suggested that ocean food chains had played a role, perhaps through seabird guano being used to fertilize the maize.

Most parrot species molt and regrow feathers about once a year, though it can vary by a few months, so these birds must have spent at least six to 18 months in Ychsma territory before being plucked for someone’s funerary headdress. And that means that someone in the Amazon was trading with the Yschma, handing over not just bundles of feathers but live parrots.

Archaeologists found similar evidence in mummified parrots, buried as ritual offerings, at the trading city of Pica, roughly 1,000 kilometers south of Pachacamac in Chile’s Atacama Desert. Pica thrived from around 900 CE to around 1400 CE, the same pre-Inca period as Pachacamac.

These feathers detached from the headdress they were originally part of. Credit: Izumi Shimada

Very intrepid delivery service

Getting a bunch of parrots across the Andes Mountains alive and in reasonably good condition is not an easy task—certainly not one your faithful correspondent would volunteer for. The authors used least-cost modeling, a method that maps the most efficient or lowest-energy path across a landscape, to create a likely map of those ancient parrot-trading routes, starting from ten sites in the Amazon and ending at Pachacamac.

If river travel were an option, one potential route cuts straight east across the Andes to Pachacamac. It lines up well with historical accounts describing how the Arawak-speaking Yanesha people traveled along very similar paths to trade in the coastal valleys of central Peru.

Another route crosses the Andes further north, ending up around Chimú, home of the Kingdom of Chimor, the largest of the post-Wari, pre-Inca kingdoms. From that area of northern Peru, it then follows the coastline southward to Pachacamac. Archaeological evidence already shows that Chimor traded with the Chachapoyas culture, located in the cloud forests on the eastern slopes of the Andes. And their “people were known for their bird-catching skills,” according to Olah and his colleagues.

Since both of these routes are supported by archaeological and historical evidence, it’s entirely possible that the Ychsma were getting their parrots through both networks. Presumably, they must have been sending back valuable goods in return.

“Transporting goods such a great distance by land and/or sea raises the questions of the high costs involved,” wrote Olah and his colleagues. But for people in both the Andes highlands and along the arid coasts, the parrots and their colorful, exotic feathers were presumably worth whatever it cost to get them. In other words, the most affluent and powerful people among the Ychsma and their neighbors were willing to make it worth the Amazon traders’ while to procure and deliver the birds.

(Unfortunately, that’s still true of unscrupulous pet breeders and collectors today.)

“This study also provided a deep historical context for a human fascination with colorful parrots that today drives a destructive illegal trade threatening their very survival,” Olah and his colleagues wrote.

Nature Communications, 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-026-69167-9 (About DOIs).

Centuries before the Inca, Peru’s wealthy imported parrots from afar Read More »