OpenAI spills technical details about how its AI coding agent works

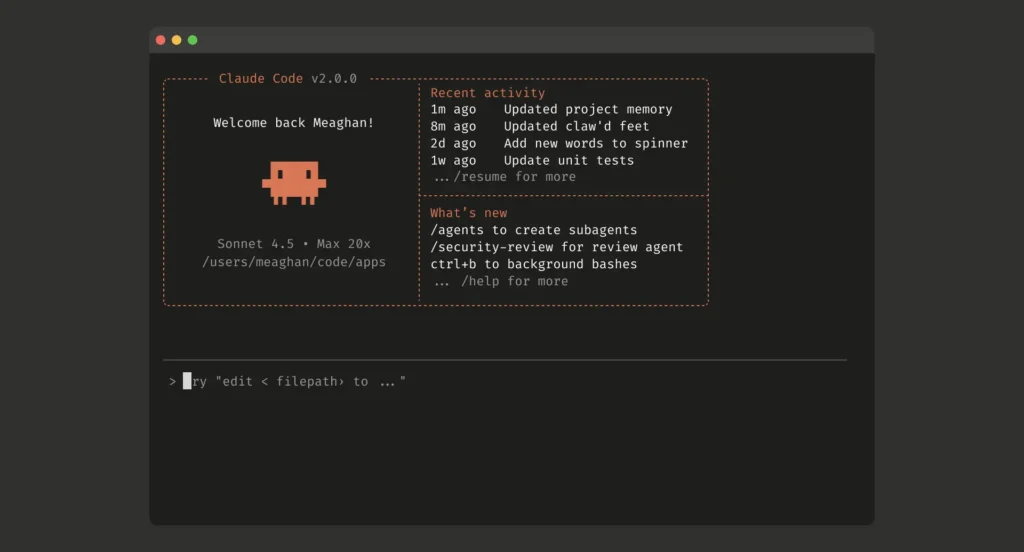

It’s worth noting that both OpenAI and Anthropic open-source their coding CLI clients on GitHub, allowing developers to examine the implementation directly, whereas they don’t do the same for ChatGPT or the Claude web interface.

An official look inside the loop

Bolin’s post focuses on what he calls “the agent loop,” which is the core logic that orchestrates interactions between the user, the AI model, and the software tools the model invokes to perform coding work.

As we wrote in December, at the center of every AI agent is a repeating cycle. The agent takes input from the user and prepares a textual prompt for the model. The model then generates a response, which either produces a final answer for the user or requests a tool call (such as running a shell command or reading a file). If the model requests a tool call, the agent executes it, appends the output to the original prompt, and queries the model again. This process repeats until the model stops requesting tools and instead produces an assistant message for the user.

That looping process has to start somewhere, and Bolin’s post reveals how Codex constructs the initial prompt sent to OpenAI’s Responses API, which handles model inference. The prompt is built from several components, each with an assigned role that determines its priority: system, developer, user, or assistant.

The instructions field comes from either a user-specified configuration file or base instructions bundled with the CLI. The tools field defines what functions the model can call, including shell commands, planning tools, web search capabilities, and any custom tools provided through Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers. The input field contains a series of items that describe the sandbox permissions, optional developer instructions, environment context like the current working directory, and finally the user’s actual message.

OpenAI spills technical details about how its AI coding agent works Read More »