Congress moves to reject bulk of White House’s proposed NASA cuts

Fewer robots, more humans

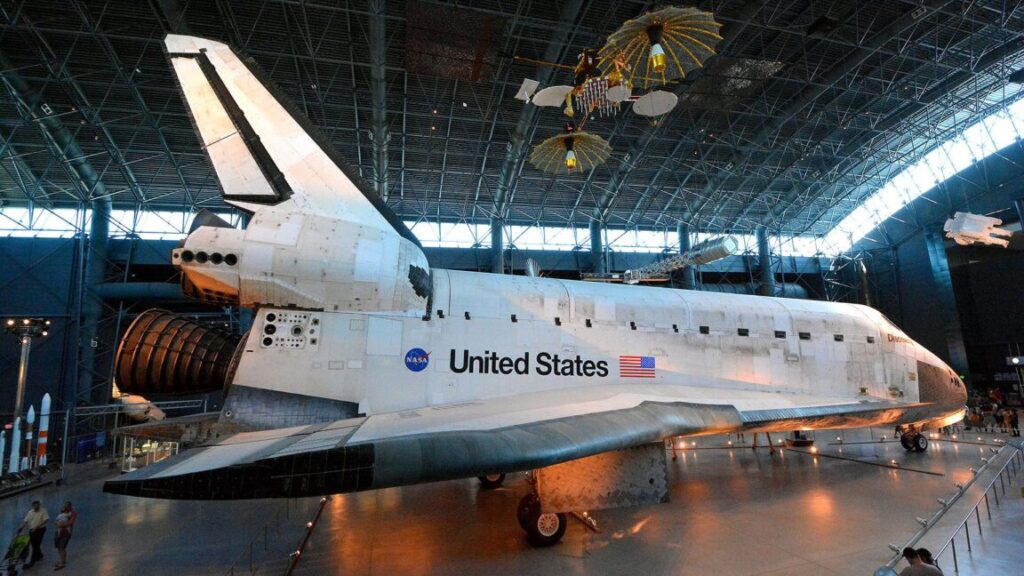

The House version of NASA’s fiscal year 2026 budget includes $9.7 billion for exploration programs, a roughly 25 percent boost over NASA’s exploration budget for 2025, and 17 percent more than the Trump administration’s request in May. The text of the House bill released publicly doesn’t include any language explicitly rejecting the White House’s plan to terminate the SLS and Orion programs after two more missions.

Instead, it directs NASA to submit a five-year budget profile for SLS, Orion, and associated ground systems to “ensure a crewed launch as early as possible.” A five-year planning budget seems to imply that the House committee wants SLS and Orion to stick around. The White House budget forecast zeros out funding for both programs after 2028.

The House also seeks to provide more than $4.1 billion for NASA’s space operations account, a slight cut from 2025 but well above the White House’s number. Space operations covers programs like the International Space Station, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, and funding for new privately owned space stations to replace the ISS.

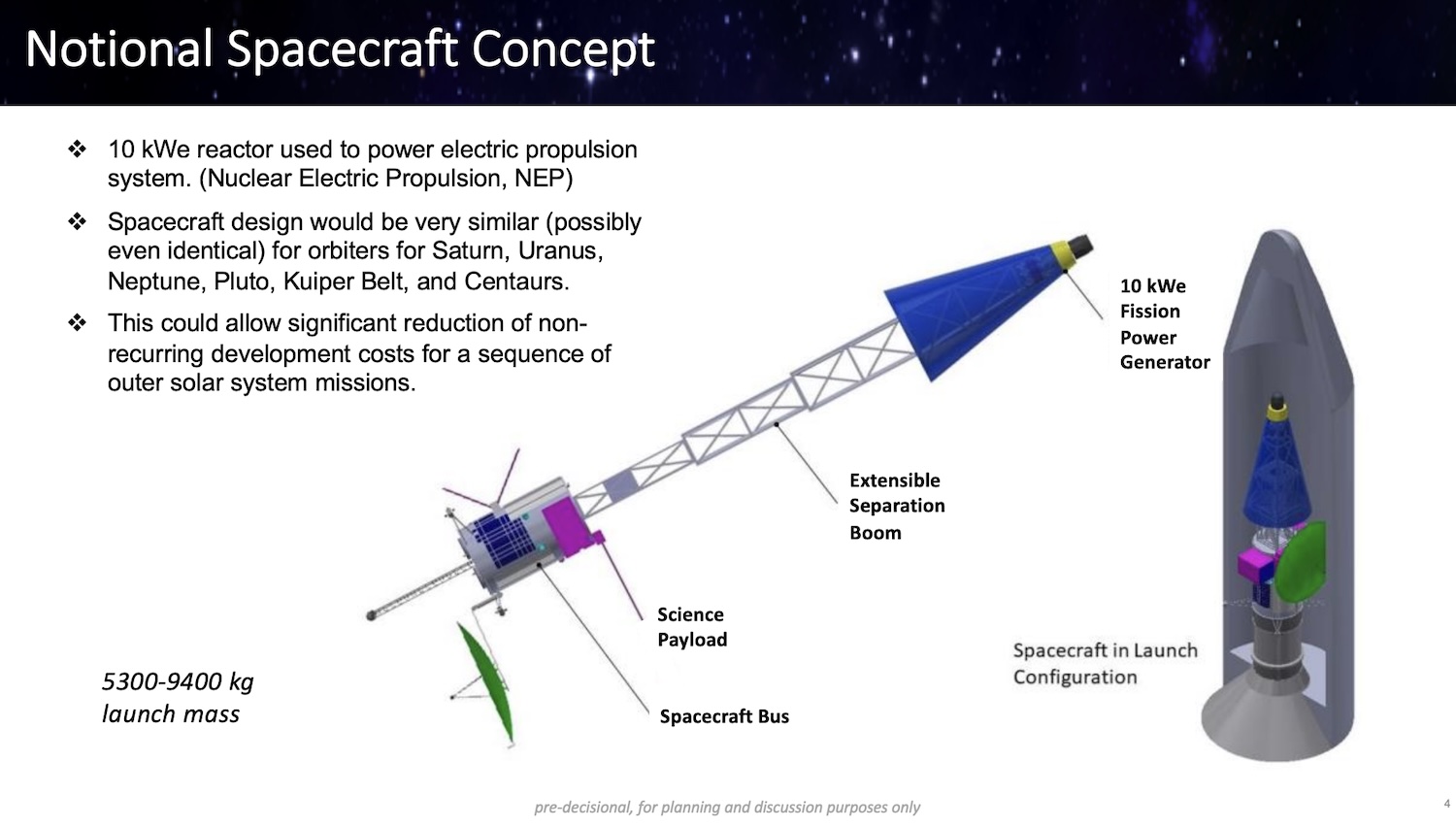

Many of NASA’s space technology programs would also be salvaged in the House budget, which allocates $913 million for tech development, a reduction from the 2025 budget but still an increase over the Trump administration’s request.

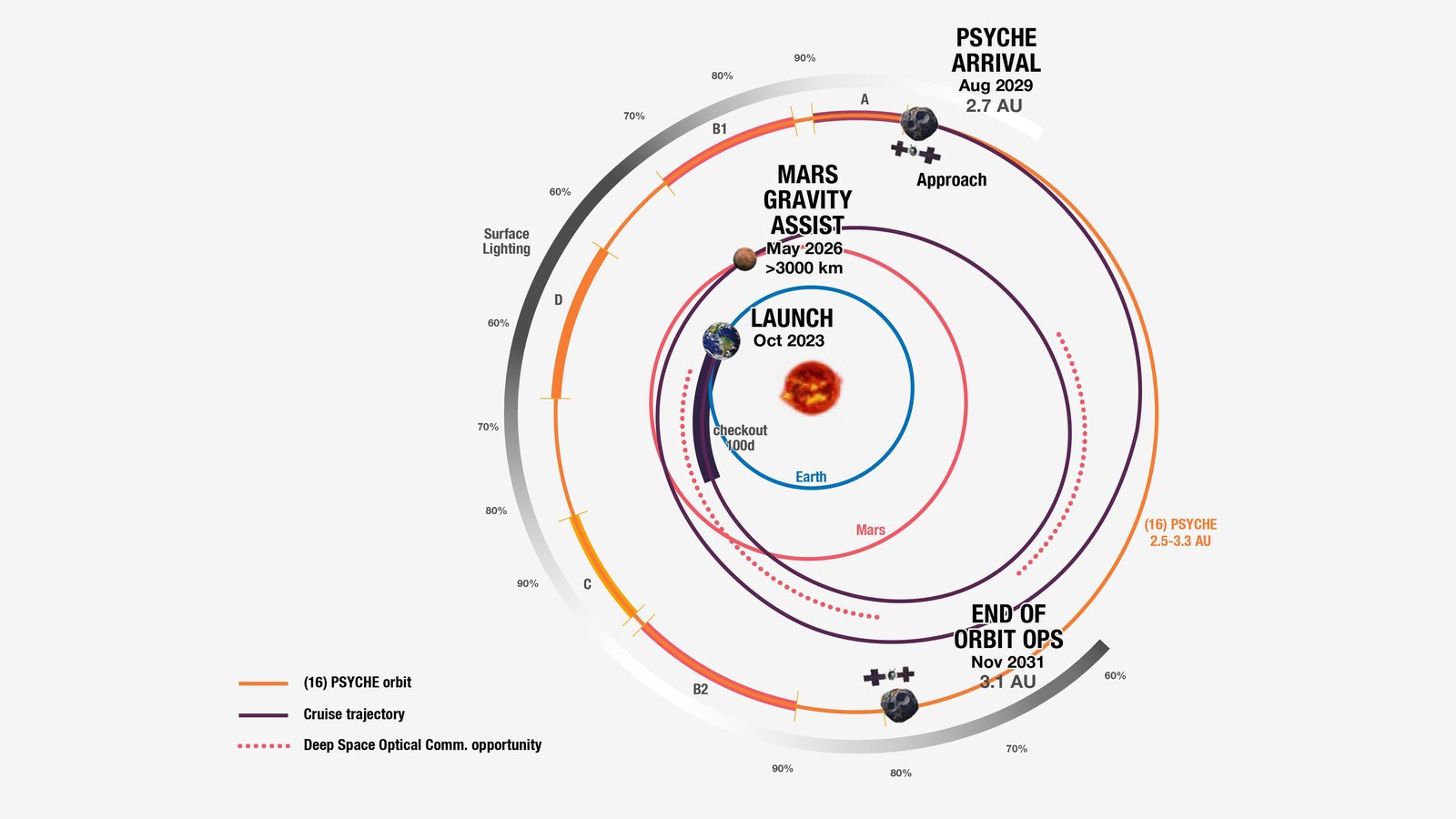

The House bill’s cuts to science and space technology, though more modest than those proposed by the White House, would still likely result in cancellations and delays for some of NASA’s robotic space missions.

Rep. Grace Meng (D-NY), the senior Democrat on the House subcommittee responsible for writing NASA’s budget, called out the bill’s cut to the agency’s science portfolio.

“As other countries are racing forward in space exploration and climate science, this bill would cause the US to fall behind by cutting NASA’s account by over $1.3 billion,” she said Tuesday.

Lawmakers reported the Senate spending bill to the full Senate Appropriations Committee last week by voice vote. Members of the House subcommittee advanced their bill to the full committee Tuesday afternoon by a vote of 9-6.

The budget bills will next be sent to the full appropriations committees of each chamber for a vote and an opportunity for amendments, before moving on to the floor for a vote by all members.

It’s still early in the annual appropriations process, and a final budget bill is likely months away from passing both houses of Congress and heading to President Donald Trump’s desk for signature. There’s no guarantee Trump will sign any congressional budget bill, or that Congress will finish the appropriations process before this year’s budget runs out on September 30.

Congress moves to reject bulk of White House’s proposed NASA cuts Read More »