NASA is kind of a mess: Here are the top priorities for a new administrator

After a long summer and fall of uncertainty, private astronaut Jared Isaacman has been renominated to lead NASA, and there appears to be momentum behind getting him confirmed quickly as the space agency’s 15th administrator. It is possible, although far from a lock, the Senate could finalize his nomination before the end of this year.

It cannot happen soon enough.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is, to put it bluntly, kind of a mess. This is not meant to disparage the many fine people who work at NASA. But years of neglect, changing priorities, mismanagement, creeping bureaucracy, meeting bloat, and other factors have taken their toll. NASA is still capable of doing great things. It still inspires. But it needs a fresh start.

“Jared has already garnered tremendous support from nearly everyone in the space community,” said Lori Garver, who served as NASA’s deputy administrator under President Obama. “This should give him a tail wind as he inevitably will have to make tough calls.”

Garver worked for a Democratic administration, and it’s notable that Isaacman has admirers from across the political spectrum, from left-leaning space advocates to right-wing influencers. A decade and a half ago, Garver led efforts to get NASA to more fully embrace commercial space. In some ways, Isaacman will seek to further this legacy, and Garver knows all too well how difficult it is to change the sprawling space agency and beat back entrenched contractors.

“Expectations are high, yet the challenge of marrying outsized goals to greatly reduced budget guidance from his administration remains,” Garver said. “It will be difficult to deliver on accelerating Artemis, transitioning to commercial LEO destinations, starting a serious nuclear electric propulsion program for Mars transportation, and attracting non-government funding for science missions. He’s coming in with a lot of support, which he will need in the current divisive political environment.”

Here’s a rundown of some of the challenges Isaacman must overcome to be a successful administrator.

A shrunken NASA

At the beginning of this year, the civil servant workforce at the space agency numbered about 18,000 people. NASA said that about 3,870 employees exited this year under various deferred resignation, early retirement, or buyout programs. After subtracting another 500 employees who left through normal attrition, NASA’s headcount will be down by 20 to 25 percent by the end of this year.

The question is how impactful these losses are. A number of the departures were from senior positions, leaving important divisions—such as Astrophysics—with acting directors and interim people in key positions. Some people who left were nearing retirement, and this may ultimately benefit the space agency by allowing younger people to bring new energy to the mission.

Yet there are very real concerns about NASA’s ability to retain its best people. As the commercial space industry grows around some of its key centers, including Alabama, Florida, and Texas, these companies cherry-pick the best NASA engineers by offering higher salaries and stock options. These engineers, in turn, know who to hire at the local field centers who are most promising.

This brain drain diminishes the engineering excellence at NASA. Can Isaacman do more with less?

Very low morale

Isaacman also arrives after what has essentially been a lost year for NASA.

Imagine you’re a NASA employee. You came to the agency to lead exploration of the Solar System and beyond. Then the second Trump administration shows up and demands widespread workforce cuts. The White House subsequently also proposes a 25 percent hit to the space agency’s budget and draconian cuts for NASA’s science programs.

Then, to cap off the spring of 2025, Isaacman’s nomination was pulled for purely political reasons. Not everyone at NASA liked Isaacman. There was genuine concern that he would shake things up and rattle cages. But Isaacman was also perceived as young, dynamic, and well-liked by the broader space community. He genuinely wanted to see NASA succeed. And then—poof—he’s gone. This only exacerbated uncertainty about the agency’s future.

Interim NASA Administrator Sean Duffy provides remarks at a briefing prior to the Crew 11 launch in August. Credit: NASA

Isaacman’s de-nomination was followed by the appointment of Sean Duffy, a former reality TV star serving as the Secretary of Transportation, to lead NASA on an interim basis. Duffy was a wild card, but it soon became clear he saw NASA as a vehicle to further his political career. And even if Duffy had been focused on solutions, he knew little about space and already had a full-time job leading the Department of Transportation. NASA employees are not fools. They saw this and understood this move’s implications.

Finally, in a coup de grâce, the government shut down on October 1. The majority of NASA’s civil servant workforce has been sitting at home for six weeks, not getting paid, not exploring, and wondering just what the hell they’re doing working for NASA.

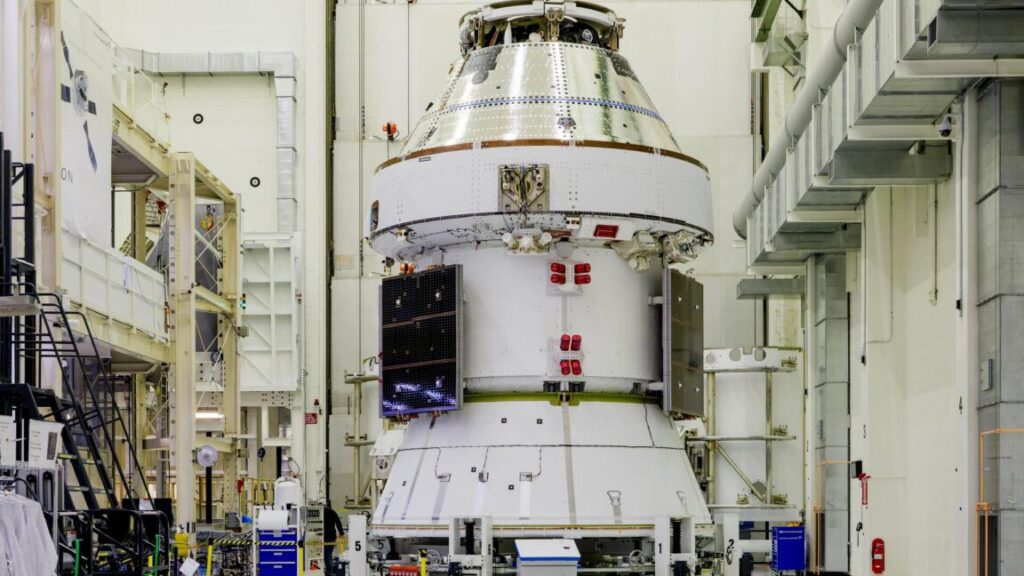

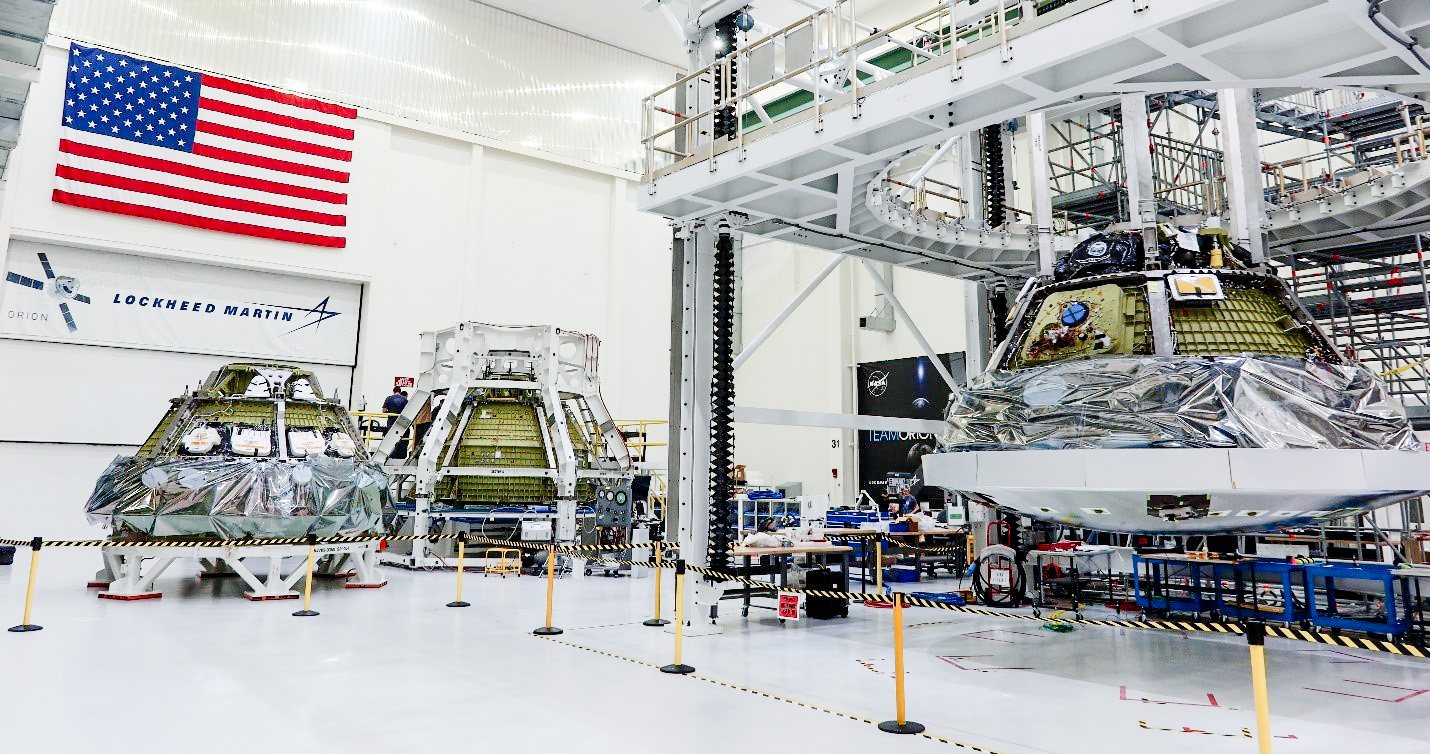

Arte-miss?

As NASA has struggled this year, China has made demonstrable progress in its lunar program. It is now probable that China’s Lanyue lander will put humans on the lunar surface by or before the year 2030, likely beating NASA in its return to the Moon with the Artemis Program.

NASA’s lunar program was created during the first Trump administration, but then NASA leader Jim Bridenstine was unable to secure enough funding (remember the whole Pell Grant fiasco?) before he left office in early 2021. This left NASA without the resources it needed to build a management team to lead the program and support key elements, including a lander and lunar spacesuits.

These problems more or less persisted under President Joe Biden and his NASA Administrator, Bill Nelson. From 2021 to 2024, the leaders of NASA essentially said everything was fine and that a lunar landing by 2026 was on track. When reporters, including myself, would ask the leaders of the Artemis Program, we were effectively shouted down.

For example, in January 2024, I pressed NASA’s chief of deep space exploration, Jim Free, about the non-viability of a 2026 human landing date.

“It’s interesting because we have 11 people in industry on here that have signed contracts to meet those dates,” Free replied during a teleconference, which included representatives from SpaceX, Axiom, and the other companies. “So from my perspective, the people in industry are here today saying we support it. We’ve signed contracts to those dates on the government side based on the technical details that they’ve given us, that our technical teams have come forward with.”

A shorter version of that might be: “Shut up, we know what we’re doing.”

NASA has already delayed the lunar landing officially to 2027. And no one believes that date is real. One of Isaacman’s first jobs will be to conduct an honest assessment of where the Artemis Program truly is and to rapidly take steps to get it on track. I think we can be confident he will do so with eyes wide open.

Human Landing System

So what will he do about this? The biggest challenge involves the Human Landing System (HLS), a necessary component to get humans to the surface from lunar orbit and back.

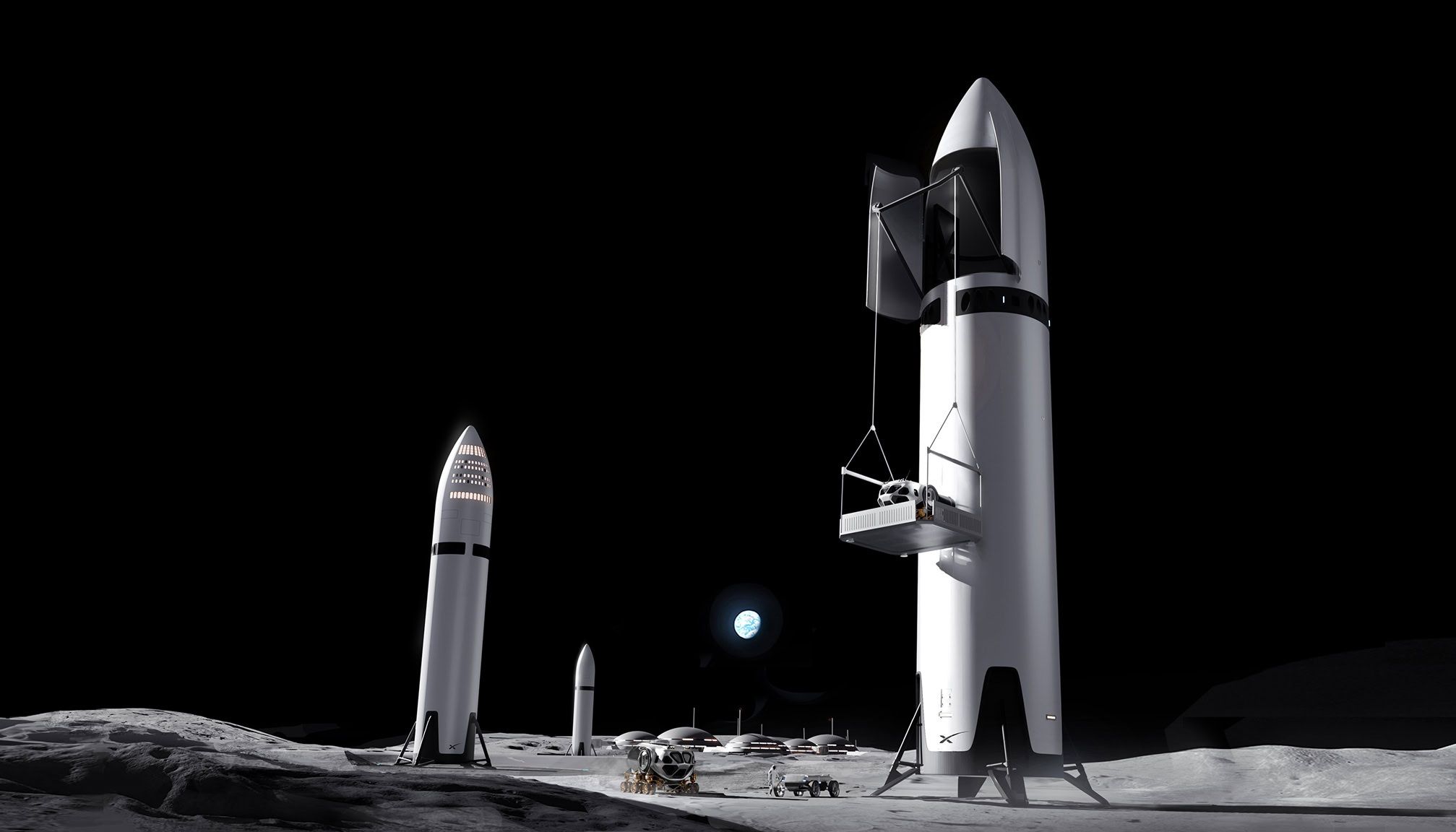

Ars explored how NASA found itself in this predicament in a long article published in early October. As for what to do now, NASA basically has two realistic options going forward. It can light a fire under SpaceX to prioritize the HLS component of its Starship program, and possibly adopt a simplified architecture. Or it can work with Blue Origin to develop to a human system using its Blue Moon Mk. 1 lander (originally intended for cargo) and a modified Mk. 1 lander for ascent purposes. (Blue says it is game). Beyond that, there is no hardware in work that could possibly accommodate a landing before 2030.

Duffy initially blustered about American capabilities. Repeatedly, he said, “We are going to beat the Chinese to the Moon.” It sounded good, but it underlined his inexperience with spaceflight because it was just not true.

Less than a month ago, Duffy changed his tune. He blamed SpaceX and its Starship vehicle for delays to Artemis, and he said he was “opening up” the lander competition. The problem is that Duffy’s solution was to raise the prospect of a “government option” lunar lander. He had been having discussions with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and others about the possibility of issuing a cost-plus contract to build a smaller lunar lander in 30 months.

An artist’s illustration of multiple Starships on the lunar surface, with a Moon base in the background. Credit: SpaceX

Duffy should have known that this timeline was completely unrealistic. Moreover, a rapidly built lunar lander (think five years, at a bare minimum) would likely cost on the order of $20 billion, which NASA did not have. But no one in his inner circle, including Amit Kshatriya, NASA’s associate administrator, was telling him that. They were encouraging him.

Isaacman is not going to be snowed under by this kind of (preposterous) proposal. Most likely, he will push SpaceX to prioritize HLS and be eager to work with Blue Origin to develop a human lander based on Mk. 1 technology.

His first call as administrator may well be to Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos.

Commercial LEO Destinations

Another looming problem involves commercial space stations in low-Earth orbit, which are supposed to be flying before the end of 2030 when the International Space Station is due to be retired.

There is much uncertainty over whether the primary companies involved in this effort—be it for financial, technical, regulatory, or other reasons—will be able to launch and test space stations by 2030 in order to allow NASA to maintain a continuous presence in low-Earth orbit. The main contractors are Axiom Space, Voyager Technologies, Blue Origin, and Vast Space.

This is one area in which Duffy took action. In August, he signed a document that implemented major changes to the Commercial LEO Destinations program. One of the biggest shifts was a lowering of the minimum requirements. Instead of fully operational stations, the new directive required only the capability to support four astronauts for 1-month increments in low-Earth orbit.

However, it is unclear that Duffy fully understood what he was signing, because there was an immediate pushback. Moreover, prior to the government shutdown, there was a lot of discussion about ripping up the directive and reverting to the old rules for commercial space stations. Everyone in the industry is scratching their heads about what comes next.

In the meantime, the space station companies are trying to raise funds, design stations for uncertain requirements, and prepare for competition for the next phase of NASA awards. This program needs more funding, clarity, and urgency for it to be successful.

Earth science

In recent days, there has been some excellent reporting about the fate of Earth science at NASA, which is part of the space agency’s core mission. Space.com published a long feature article about the Trump administration’s efforts to undermine Maryland’s Goddard Space Flight Center, which is NASA’s oldest field center.

Goddard houses the largest Earth science workforce at the agency, and its study of climate change is at odds with the policy positions of the Trump administration and many members of a Republican-controlled Congress. The result has been steep funding cuts, canceled missions, and closed buildings.

One of Isaacman’s most challenging jobs will be to balance support for Earth science while also placating an administration that frankly does not want to publish reports about how human activity is warming the planet.

In remarks on the social media site X, Isaacman recently said he wanted to expand commercial partnerships to science missions. “Better to have 10 x $100 million missions and a few fail than a single overdue and costly $1B+ mission,” he wrote. Isaacman said NASA should also buy more Earth data from providers like Planet and BlackSky, which already have satellites in orbit.

“Why build bespoke satellites at greater cost and delay when you could pay for the data as needed from existing providers?” he asked.

Planetary science

Another area of concern is planetary science. When one picks apart Trump’s budget priorities, there are two clear and disturbing trends.

The first is that there are no significant planetary science missions in the pipeline after the ambitious Dragonfly mission, which is scheduled to launch to Titan in July 2028. It becomes difficult to escape the reality that this administration is not prioritizing any mission that launches after Trump leaves office in January 2029. As a result, after Dragonfly, the planetary pipeline is running low.

Another major concern is the fate of the famed Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. The lab laid off 550 people last month, which followed previous cuts. The center director, Laurie Leshin, stepped down on June 1. With the Mars Sample Return mission on hold, and quite possibly canceled, the future of NASA’s premier planetary science mission center is cloudy.

A view of the control room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Credit: NASA

Isaacman has said he has never “remotely suggested” that NASA could do without the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“Personally, I have publicly defended programs like the Chandra X-ray Observatory, offered to fund a Hubble reboost mission, and anything suggesting that I am anti-science or want to outsource that responsibility is simply untrue,” he wrote on X.

That is likely true, but charting a bright course for the future of planetary science, on a limited budget, will be a major challenge for the new administrator.

New initiatives

All of the above concerns NASA’s existing challenges. But Isaacman will certainly want to make his own mark. This is likely to involve a spaceflight technology he considers to be the missing link in charting a course for humans to explore the Solar System beyond the Moon: nuclear electric propulsion.

As he explained to Ars earlier this year, Isaacman’s signature issue was going to be a full-bore push into nuclear electric propulsion.

“We would have gone right to a 100-kilowatt test vehicle that we would send somewhere inspiring with some great cameras,” he said. “Then we are going right to megawatt class, inside of four years, something you could dock a human-rated spaceship to, or drag a telescope to a Lagrange point and then return, big stuff like that. The goal was to get America underway in space on nuclear power.”

Another key element of this plan is that it would give some of NASA’s field centers, including Marshall Space Flight Center, important work to do after the seemingly inevitable cancellation of the Space Launch System rocket.

Standing up new programs, and battling against existing programs that have strong backing in Congress and industry, will require all of the diplomatic skill and force of personality Isaacman can muster.

We will soon find out if he has the right stuff.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

NASA is kind of a mess: Here are the top priorities for a new administrator Read More »