When Europe needed it most, the Ariane 6 rocket finally delivered

“For this sovereignty, we must yield to the temptation of preferring SpaceX.”

Europe’s second Ariane 6 rocket lifted off from the Guiana Space Center on Thursday with a French military spy satellite. Credit: ESA-CNES-Arianespace-P. Piron

Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket lifted off Thursday from French Guiana and deployed a high-resolution reconnaissance satellite into orbit for the French military, notching a success on its first operational flight.

The 184-foot-tall (56-meter) rocket lifted off from Kourou, French Guiana, at 11: 24 am EST (16: 24 UTC). Twin solid-fueled boosters and a hydrogen-fueled core stage engine powered the Ariane 6 through thick clouds on an arcing trajectory north from the spaceport on South America’s northeastern coast.

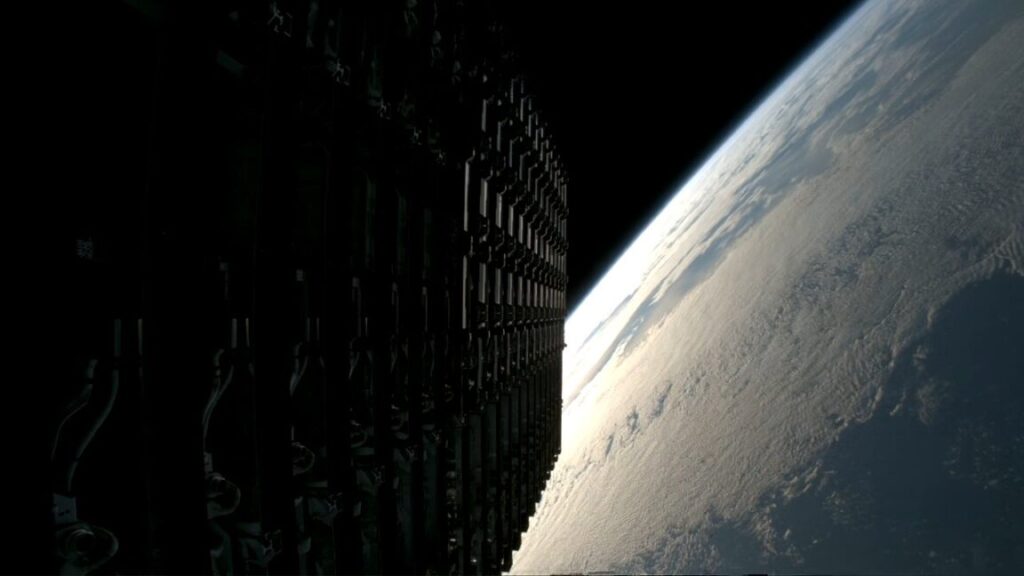

The rocket shed its strap-on boosters a little more than two minutes into the flight, then jettisoned its core stage nearly eight minutes after liftoff. The spent rocket parts fell into the Atlantic Ocean. The upper stage’s Vinci engine ignited two times to reach a nearly circular polar orbit about 500 miles (800 kilometers) above the Earth. A little more than an hour after launch, the Ariane 6 upper stage deployed CSO-3, a sharp-eyed French military spy satellite, to begin a mission providing optical surveillance imagery to French intelligence agencies and military forces.

“This is an absolute pleasure for me today to announce that Ariane 6 has successfully placed into orbit the CSO-3 satellite,” said David Cavaillolès, who took over in January as CEO of Arianespace, the Ariane 6’s commercial operator. “Today, here in Kourou, we can say that thanks to Ariane 6, Europe and France have their own autonomous access to space back, and this is great news.”

This was the second flight of Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket, following a mostly successful debut launch last July. The first test flight of the unproven Ariane 6 carried a batch of small, relatively inexpensive satellites. An Auxiliary Propulsion Unit (APU)—essentially a miniature second engine—on the upper stage shut down in the latter portion of the inaugural Ariane 6 flight, after the rocket reached orbit and released some of its payloads. But the unit malfunctioned before a third burn of the upper stage’s main engine, preventing the Ariane 6 from targeting a controlled reentry into the atmosphere.

The APU has several jobs on an Ariane 6 flight, including maintaining pressure inside the upper stage’s cryogenic propellant tanks, settling propellants before each main engine firing, and making fine adjustments to the rocket’s position in space. The APU appeared to work as designed Thursday, although this launch flew a less demanding profile than the test flight last year.

Is Ariane 6 the solution?

Ariane 6 has been exorbitantly costly and years late, but its first operational success comes at an opportune time for Europe.

Philippe Baptiste, France’s minister for research and higher education, says Ariane 6 is “proof of our space sovereignty,” as many European officials feel they can no longer rely on the United States. Baptiste, an engineer and former head of the French space agency, mentioned “sovereignty” so many times, turning his statement into a drinking game crossed my mind.

“The return of Donald Trump to the White House, with Elon Musk at his side, already has significant consequences on our research partnerships, on our commercial partnerships,” Baptiste said. “Should I mention the uncertainties weighing today on our cooperation with NASA and NOAA, when emblematic programs like the ISS (International Space Station) are being unilaterally questioned by Elon Musk?

“If we want to maintain our independence, ensure our security, and preserve our sovereignty, we must equip ourselves with the means for strategic autonomy, and space is an essential part of this,” he continued.

Philippe Baptiste arrives at a government question session at the Senate in Paris on March 5, 2025. Credit: Magali Cohen/Hans Lucas/AFP via Getty Images

Baptiste’s comments echo remarks from a range of European leaders in recent weeks.

French President Emmanuel Macron said in a televised address Wednesday night that the French were “legitimately worried” about European security after Trump reversed US policy on Ukraine. America’s NATO allies are largely united in their desire to continue supporting Ukraine in its defense against Russia’s invasion, while the Trump administration seeks a ceasefire that would require significant Ukrainian concessions.

“I want to believe that the United States will stay by our side, but we have to be prepared for that not to be the case,” Macron said. “The future of Europe does not have to be decided in Washington or Moscow.”

Friedrich Merz, set to become Germany’s next chancellor, said last month that Europe should strive to “achieve independence” from the United States. “It is clear that the Americans, at least this part of the Americans, this administration, are largely indifferent to the fate of Europe.”

Merz also suggested Germany, France, and the United Kingdom should explore cooperation on a European nuclear deterrent to replace that of the United States, which has committed to protecting European territory from Russian attack for more than 75 years. Macron said the French military, which runs the only nuclear forces in Europe fully independent of the United States, could be used to protect allies elsewhere on the continent.

Access to space is also a strategic imperative for Europe, and it hasn’t come cheap. ESA paid more than $4 billion to develop the Ariane 6 rocket as a cheaper, more capable replacement for the Ariane 5, which retired in 2023. There are still pressing questions about Ariane 6’s cost per launch and whether the rocket will ever be able to meet its price target and compete with SpaceX and other companies in the commercial market.

But European officials have freely admitted the commercial market is secondary on their list of Ariane 6 goals.

European satellite operators stopped launching their payloads on Russian rockets after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Now, with Elon Musk inserting himself into European politics, there’s little appetite among European government officials to launch their satellites on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket.

The second Ariane 6 rocket on the launch pad in French Guiana. Credit: ESA–S. Corvaja

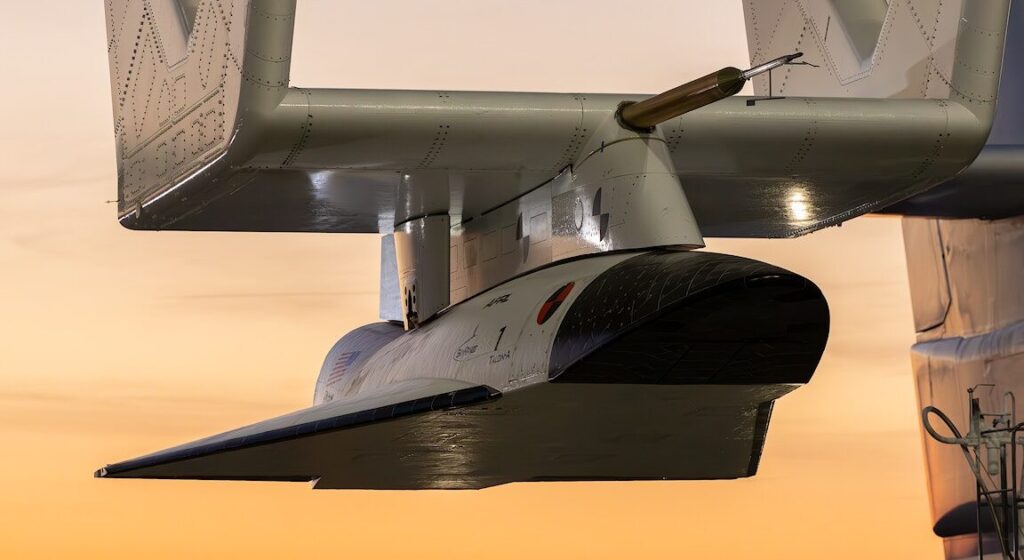

The Falcon 9 was the go-to choice for the European Space Agency, the European Union, and several national governments in Europe after they lost access to Russia’s Soyuz rocket and when Europe’s homemade Ariane 6 and Vega rockets faced lengthy delays. ESA launched a $1.5 billion space telescope on a Falcon 9 rocket in 2023, then returned to SpaceX to launch a climate research satellite and an asteroid explorer last year. The European Union paid SpaceX to launch four satellites for its flagship Galileo navigation network.

European space officials weren’t thrilled to do this. ESA was somewhat more accepting of the situation, with the agency’s director general recognizing Europe was suffering from an “acute launcher crisis” two years ago. On the other hand, the EU refused to even acknowledge SpaceX’s role in delivering Galileo satellites to orbit in the text of a post-launch press release.

“For this sovereignty, we must yield to the temptation of preferring SpaceX or another competitor that may seem trendier, more reliable, or cheaper,” Baptiste said. “We did not yield for CSO-3, and we will not yield in the future. We cannot yield because doing so would mean closing the door to space for good, and there would be no turning back. This is why the first commercial launch of Ariane 6 is not just a technical and one-off success. It marks a new milestone, essential in the choice of European space independence and sovereignty.”

Two flights into its career, Ariane 6 seems to offer a technical solution for Europe’s needs. But at what cost? Arianespace hasn’t publicly disclosed the cost for an Ariane 6 launch, although it’s likely somewhere in the range of 80 million to 100 million euros, about 40 percent lower than the cost of an Ariane 5. This is about 50 percent more than SpaceX’s list price for a dedicated Falcon 9 launch.

A new wave of European startups should soon begin launching small rockets to gain a foothold in the continent’s launch industry. These include Isar Aerospace, which could launch its first Spectrum rocket in a matter of weeks. These companies have the potential to offer Europe an option for cheaper rides to space, but the startups won’t have a rocket in the class of Ariane 6 until at least the 2030s.

Until then, at least, European governments will have to pay more to guarantee autonomous access to space.

When Europe needed it most, the Ariane 6 rocket finally delivered Read More »