Reviewing iOS 26 for power users: Reminders, Preview, and more

These features try to turn iPhones into more powerful work and organization tools.

iOS 26 came out last week, bringing a new look and interface alongside some new capabilities and updates aimed squarely at iPhone power users.

We gave you our main iOS 26 review last week. This time around, we’re taking a look at some of the updates targeted at people who rely on their iPhones for much more than making phone calls and browsing the Internet. Many of these features rely on Apple Intelligence, meaning they’re only as reliable and helpful as Apple’s generative AI (and only available on newer iPhones, besides). Other adjustments are smaller but could make a big difference to people who use their phone to do work tasks.

Reminders attempt to get smarter

The Reminders app gets the Apple Intelligence treatment in iOS 26, with the AI primarily focused on making it easier to organize content within Reminders lists. Lines in Reminders lists are often short, quickly jotted-down blurbs rather than lengthy, detailed complex instructions. With this in mind, it’s easy to see how the AI can sometimes lack enough information in order to perform certain tasks, like logically grouping different errands into sensible sections.

But Apple also encourages applying the AI-based Reminders features to areas of life that could hold more weight, such as making a list of suggested reminders from emails. For serious or work-critical summaries, Reminders’ new Apple Intelligence capabilities aren’t reliable enough.

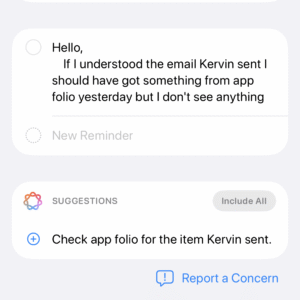

Suggested Reminders based on selected text

iOS 26 attempts to elevate Reminders from an app for making lists to an organization tool that helps you identify information or important tasks that you should accomplish. If you share content, such as emails, website text, or a note, with the app, it can create a list of what it thinks are the critical things to remember from the text. But if you’re trying to extract information any more advanced than an ingredients list from a recipe, Reminders misses the mark.

Sometimes I tried sharing longer text with Reminders and didn’t get any suggestions. Credit: Scharon Harding

Sometimes, especially when reviewing longer text, Reminders was unable to think of suggested reminders. Other times, the reminders that it suggested, based on lengthy messages, were off-base.

For instance, I had the app pull suggested reminders from a long email with guidelines and instructions from an editor. Highlighting a lot of text can be tedious on a touchscreen, but I did it anyway because the message had lots of helpful information broken up into sections that each had their own bold subheadings. Additionally, most of those sections had their own lists (some using bullet points, some using numbers). I hoped Reminders would at least gather information from all of the email’s lists. But the suggested reminders ended up just being the same text from three—but not all—of the email’s bold subheadings.

When I tried getting suggested reminders from a smaller portion of the same email, I surprisingly got five bullet points that covered more than just the email’s subheadings but that still missed key points, including the email’s primary purpose.

Ultimately, the suggested Reminders feature mostly just boosts the app’s ability to serve as a modern shopping list. Suggested Reminders excels at pulling out ingredients from recipes, turning each ingredient into a suggestion that you can tap to add to a Reminders list. But being able to make a bulleted list out of a bulleted list is far from groundbreaking.

Auto-categorizing lines in Reminders lists

Since iOS 17, Reminders has been able to automatically sort items in grocery lists into distinct categories, like Produce and Proteins. iOS 26 tries taking things further by automatically grouping items in a list into non-culinary sections.

The way Reminders groups user-created tasks in lists is more sensible—and useful—than when it tries to create task suggestions based on shared text.

For example, I made a long list of various errands I needed to do, and Reminders grouped them into these categories: Administrative Tasks, Household Chores, Miscellaneous, Personal Tasks, Shopping, and Travel & Accommodation. The error rate here is respectable, but I would have tweaked some things. For one, I wouldn’t use the word “administrative” to refer to personal errands. The two tasks included under Administrative Tasks would have made more sense to me in Personal Tasks or Miscellaneous, even though those category names are almost too vague to have a distinct meaning.

Preview comes to iOS

With the iOS debut of Preview, Apple brings an app for viewing and editing PDFs and images to iPhones, which macOS users have had for years. As a result, many iPhone users will find the software easy and familiar to use.

But for iPhone owners who have long relied on Files for viewing, marking, and filling out PDFs and the like, Preview doesn’t bring many new capabilities. Anything that you can do in Preview, you could have done by viewing the same document in Files in an older version of iOS, save for a new crop tool and a dedicated button for showing information about the document.

That’s the point, though. When an iPhone has two discrete apps that can read and edit files, it’s far less frustrating to work with multiple documents. While you’re annotating a document in Preview, the Files app is still available, allowing you to have more than one document open at once. It’s a simple adjustment but one that vastly improves multitasking.

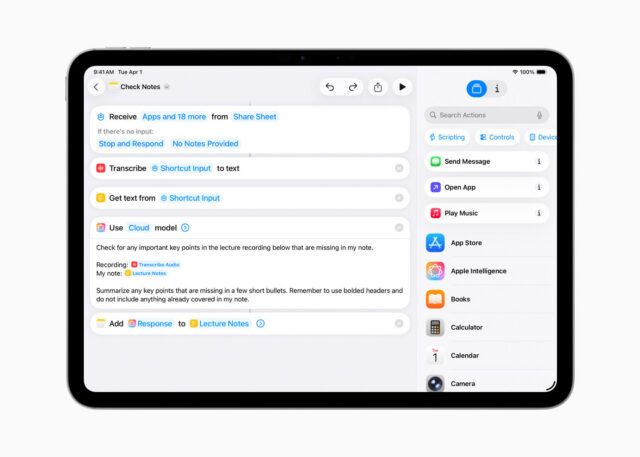

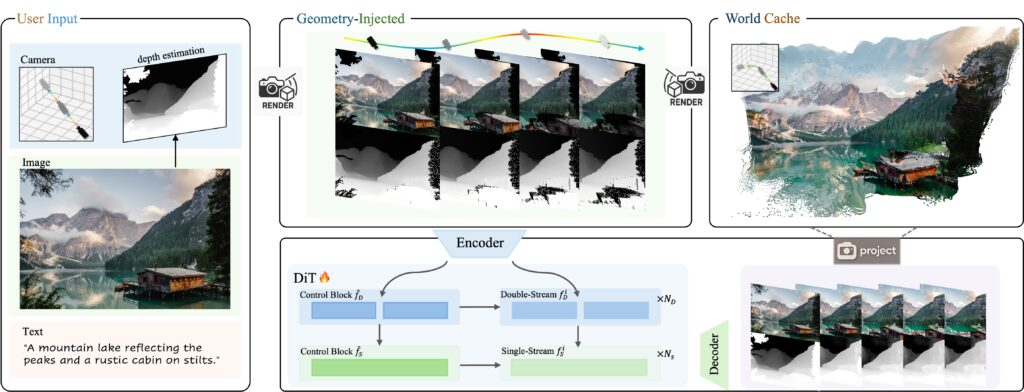

More Shortcuts options

Shortcuts gets somewhat more capable in iOS 26. That’s assuming you’re interested in using ChatGPT or Apple Intelligence generative AI in your automated tasks. You can tag in generative AI to create a shortcut that includes summarizing text in bullet points and applying that bulleted list to the shortcut’s next task, for instance.

An example of a Shortcut that uses generative AI. Credit: Apple

There are inherent drawbacks here. For one, Apple Intelligence and ChatGPT, like many generative AI tools, are subject to inaccuracies and can frequently overlook and/or misinterpret critical information. iOS 26 makes it easier for power users to incorporate a rewrite of a long text that has a more professional tone into a Shortcut. But that doesn’t mean that AI will properly communicate the information, especially when used across different scenarios with varied text.

You have three options for building Shortcuts that include the use of AI models. Using ChatGPT or Apple Intelligence via Apple’s Private Cloud Compute, which runs the model on an Apple server, requires an Internet connection. Alternatively, you can use an on-device model without connecting to the web.

You can run more advanced models via Private Cloud Compute than you can with Apple Intelligence on-device. In Apple’s testing, models via Private Cloud Compute perform better on things like writing summaries and composition compared to on-device models.

Apple says personal user data sent to Private Cloud Compute “isn’t accessible to anyone other than the user—not even to Apple.” Apple has a strong, yet flawed, reputation for being better about user privacy than other Big Tech firms. But by offering three different models to use with Shortcuts, iOS 26 ensures greater functionality, options, and control.

Something for podcasters

It’s likely that more people rely on iPads (or Macs) than iPhones for podcasting. Nevertheless, a new local capture feature introduced to both iOS 26 and iPadOS 26 makes it a touch more feasible to use iPhones (and iPads especially) for recording interviews for podcasts.

Before the latest updates, iOS and iPadOS only allowed one app to access the device’s microphone at a time. So, if you were interviewing someone via a videoconferencing app, you couldn’t also use your iPhone or iPad to record the discussion, since the videoconferencing app is using your mic to share your voice with whoever is on the other end of the call. Local capture on iOS 26 doesn’t include audio input controls, but its inclusion gives podcasters a way to record interviews or conversations on iPhones without needing additional software or hardware. That capability could save the day in a pinch.

Reviewing iOS 26 for power users: Reminders, Preview, and more Read More »