Discworld, Daleks, and Deep 13: A geeky holiday TV and movie watchlist

There’s obviously more to Christmas flicks than Netflix romcoms.

I promise that most of this list is better than the Star Wars Holiday Special. Credit: Disney

‘Tis the season for all kinds of festive titles to start appearing in our to-watch queues. For folks who celebrate Christmas in any form, there are a million different movies and TV specials vying for your attention. There are the beloved favorites that we’ll make the time to revisit year after year, plus the seemingly endless number of new titles arriving on the various streaming services this season.

But in all honesty, most of these movies are made for and by the mainstream. So if you don’t want a broad family slapstick or yet another big city girl going back to her small town to learn the meaning of Christmas, here are a few options to bring some geekiness to your screen. Make the season nerdy and bright!

Let’s get it out of the way immediately: Star Wars Holiday Special

It’s almost too bizarre to be believed, but yes, this was a thing that existed, and it lives on in legend. The cast of Star Wars returned for this TV special, where the gang goes to the Wookie planet Kashyyyk to celebrate Life Day. They’re joined by some surprising guests. Golden Girls icon Bea Arthur is in it alongside The Honeymooners’ Art Carney, acclaimed multi-disciplinary performer Diahann Carroll, and the band Jefferson Starship.

Let’s not mince words. The holiday special is bad. But it’s bad in a strangely riveting way that’s kind of hard not to enjoy. And at least it falls chronologically before The Empire Strikes Back, so you can immediately cleanse your viewing palate with one of the series’ best after one of its lowest moments. And the ice planet of Hoth practically makes Empire a Christmas movie of its own, so commit to the double feature for a full night of sci-fi.

Babylon 5‘s surprising “Fall of Night”

For most TV shows, a holiday episode is an outlier that exists separately from the main story arcs. Not so for Babylon 5. “Fall of Night” closes the show’s second season, and it manages to tie together many of the loose ends in a satisfying conclusion while also blending in many of the themes you’d expect from a Christmas episode.

It’s a bit unusual, but it’s definitely a Christmas episode. Credit: Warner Bros Discovery

There’s angelic intervention and gift-giving between Sheridan and Ivanova alongside the heavier topics of interstellar politics. The references to World War II aren’t terribly subtle, but the desperate yearning for peace in the galaxy also makes this a solid choice for science fiction fans to queue up this season.

Doctor Who, many times over

The Time Lords have gifted viewers with more than a dozen festive episodes over the many iterations of Doctor Who. Fans of the old-school series only have one true Christmas episode from the original 1960s run to check out: “The Feast of Steven.” In the modern era, though, the holidays are often when a Doctor passes the mantle to the next in line, so there are plenty of chances to cap off the starring actor’s work in fine style.

Current viewers may most closely connect the Christmas specials to the David Tennant era thanks to episodes like “The Christmas Invasion,” “The Runaway Bride,” and the epic two-parter “The End of Time.” Matt Smith also takes a turn in several strong holiday outings, particularly “The Time of the Doctor.”

Just one of several Doctor Who Christmas episodes. Credit: BBC

This is one of the few television series to treat New Year’s Eve as a winter holiday worthy of its own showpieces, particularly in the past few years. Jodie Whittaker got the NYE treatment with a trio of Dalek-centric stories, most notably with the very funny “Eve of the Daleks” episode.

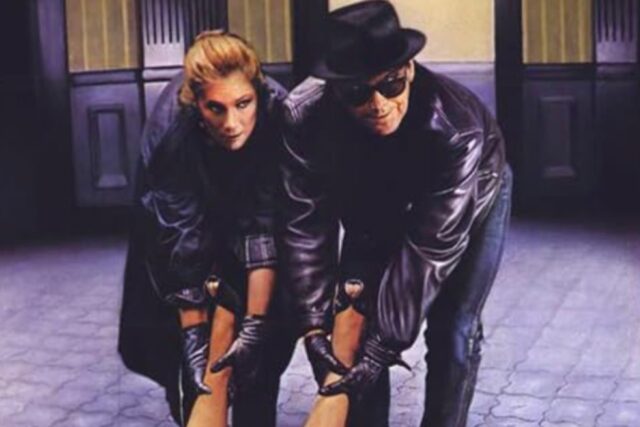

Hogfather, for a Terry Pratchett Christmas

The wildly funny fantasy author Terry Pratchett is beloved by many readers for his sprawling Discworld novels. A few directors have made the leap from page to screen with Pratchett’s stories, and Hogfather is one of the best adaptations. That could be partly because Death and Susan are two of the best characters in the whole Discworld universe, and they figure prominently in this Christmas tale. They’re also perfectly cast: Susan is played by Michelle Dockery before her rise to Downton Abbey fame, and Death is voiced by stage and screen actor Ian Richardson.

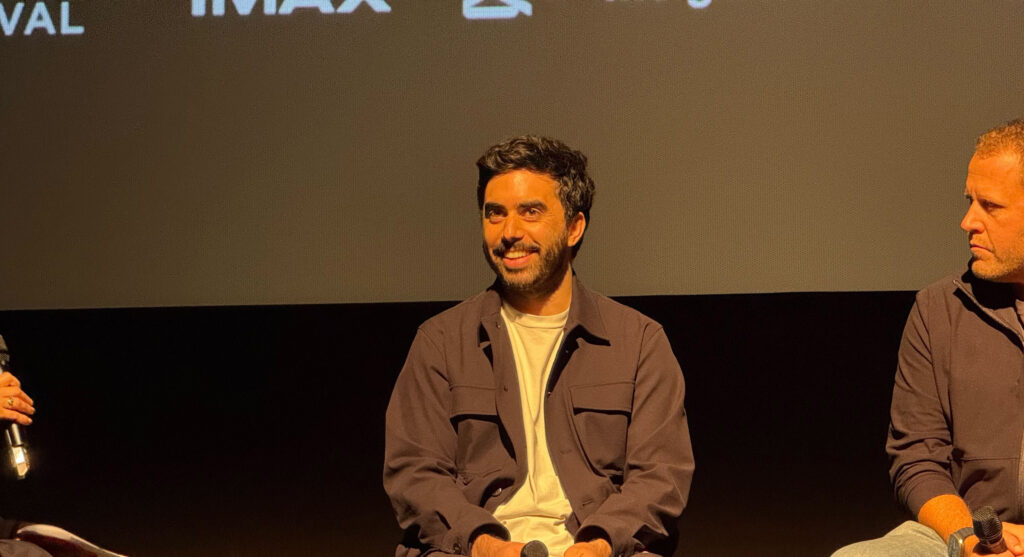

Terry Pratchett. That’s all you likely need to know. Credit: Sky One

In this Discworld take on Christmas, a shadowy group called The Auditors orders the kidnapping of the Hogfather (who bears no small resemblance to Santa Claus). To avert a holiday catastrophe, Death himself takes over the role of delivering presents on Hogswatchnight. This two-part TV movie captures all the irreverent humor that has won Pratchett so many fans over the years, and it’s a must-watch for anyone who adores that peculiar world atop the Great A’Tuin and its quartet of elephants.

Gremlins, the dark horse cult classic option

Gremlins is a cult classic for a reason and one of the more enduring movies for those who aren’t looking for everything to be bright, cheery fun during the holidays.

Fun fact: This film managed to scandalize so much that it partially led to the creation of the PG-13 rating. Credit: Disney

You can read it as a send-up of Christmas consumerism, a wacky horror-comedy flick, an impressive showcase of movie puppetry, or all three at once. Plus, it’s just so very, very ’80s. I doubt I have to say much more to sell you on it, because I’d guess most Ars readers already watch it on the regular.

Mystery Science Theater 3000, naturally

Whether it’s in the Satellite of Love or the Gizmoplex, the hilarious brains behind Mystery Science Theater 3000 can spoof any and all terrible movies, including the festive ones. I often enjoy some MST3K as a kickoff to the holiday season with the group’s Thanksgiving shows, but there’s also plenty of bad movie fun to be had in December.

There are a few standouts for true Christmas movie episodes. Experiment 321 sees Joel and bots watching Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, a truly terrible flick from the 1960s in which a Martian leader captures old Saint Nick to try and make the children on the red planet happier. For Mike fans, check out experiment 521, where the film is Santa Claus and even the host skits have a festive theme. Finally, from the Netflix era, Jonah and the bots suffer through The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t in experiment 1113. All three are excellent episodes despite the movies being the cinematic equivalent of a lump of coal in your stocking.

Joel doesn’t exactly exude holiday cheer, but that’s kind of the joke. Credit: Satellite of Love

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Some of the other experiments have movies set at Christmastime or sneak in occasional festive jokes from the cast. And if that’s still not enough to satisfy, there’s also nearly endless fodder you can find digging through the RiffTrax library—they even spoofed the Star Wars Holiday Special.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (with some Turkish delight)

Many directors have created their own spin on this C.S. Lewis story over the decades, and any of them make for a quality addition to your holiday lineup. It works for any attitude toward holiday time. If you prefer to be agnostic about it, just soak up the winter vibes created by the White Witch and maybe treat yourself to some Turkish delight while you watch. If you’re all about the presents, be sure to watch one of the versions that adheres to the books by having Father Christmas make an appearance. And if you want to honor the religious history, then enjoy the lion Aslan as a non-too-subtle analog for Jesus.

The classic BBC series probably won’t work for younger audiences today, but you had to be there, and some of us were indeed there. Credit: BBC

I’m partial to the 1988 BBC adaptation because it was the first one I saw, but the 2005 Disney film is pretty decent as well. Or, if you’ve already seen all of the Doctor Who specials enough times to quote them verbatim, make your viewing choice based on the acting crossovers, because something about Aslan seems to draw performers with ties to that show. In the animated 1979 version, Whovian actor Stephen Thorne voiced the lion, while Ronald Pickup played him in the 1988 adaptation and its sequels.

8-Bit Christmas, A Christmas Story for the ’80s

Remaking a classic is a bold endeavor. We’ve seen many an effort fall flat, especially when the source material is a near-perfect comedy like A Christmas Story. But against the odds, 8-Bit Christmas pulls off the high-wire act with charm and warmth. This version reframes the dream of the unattainable Christmas present by leaping forward a few decades. Rather than Ralphie’s quest for the Red Ryder rifle, Jake wants the latest and greatest in gaming: a Nintendo Entertainment System.

Now, if you were a gamer in your youth, there are some scenes here that will speak to your soul. There’s an early moment where Jake and the other kids on his suburban block are hanging out in the basement of one lucky boy who has an NES of his own. They’re gathered shoulder to shoulder around the tube TV, arguing over who should get the controller next. Every detail in this scene, from the sweaters and the set dressing to the look of rapture as the kids experience the power of a new console for the first time is just perfection.

The film is at least a great concept, and it delivers pretty well on it. Credit: HBO Max

There are also other cute ’80s nods; for instance, while Jake is lusting after an NES, his sister wants a Cabbage Patch doll with the same single-minded desire. Those of us who grew up in the ’80s know that feeling well. Heck, those of us who were huddled over our browsers refreshing in a panic hoping to snag the Switch 2 just earlier this year know that feeling. This geeky tale was a pleasant surprise to find among the modern-day Christmas movie productions.

The otaku choice: Tokyo Godfathers

The otaku nerds surely already know this one well, but I would be remiss not to include this anime masterwork. It’s a poignant addition to anyone’s Christmas viewing list, geek or otherwise. The film is by legendary manga artist and anime director Satoshi Kon, and it received a new English dub a few years ago that’s particularly recommended.

The film is dripping with atmosphere and creative ideas. Credit: Sony

As with so many of the best movies, it’s probably best to go in without knowing too much. The first key point is: It’s a story of three people living on the streets of Tokyo on Christmas Eve. And the second is: while the phrase is trite, Tokyo Godfathers genuinely can and will make you laugh and make you cry.

In Daria, “Depth Takes a Holiday”

In the ’90s, Daria Morgendorffer was the queen of the teenage outcasts, even though she would have hated having that title. The irreverent animated series from MTV holds up impressively well under modern scrutiny. (Although yes, in most available ways to rewatch it, the licensed music is gone. Just cue up the most important tracks you remember when you watch.)

For such an offbeat program, it’s surprising that Daria did, in fact, include a festive episode called “Depth Takes a Holiday.” In this break from the show’s usual reality, several holidays in human form appear in the Lawndale suburb, causing chaos and playing some rock music. Daria eventually agrees to help restore the natural order of things and get these holidays back to their home on Holiday Island, which is just as cliquey and pointless as Lawndale High.

It’s a controversial episode, but it has its merits. Credit: Paramount

“Depth Takes a Holiday” is pretty dang weird, and it’s a love-it or hate-it point in the third season. But I say it’s all the more reason to spend December revisiting some of my favorite Daria episodes alongside this. For those in the hate-it camp, you’ll enjoy the other episodes even more in contrast. And if you’re in the love-it audience, mark your calendar to also watch it on Guy Fawkes Day.

Honorable mention: A Christmas Carol audiobook

I realize that an audiobook is not viewing, but any Star Trek fan worth their replicator-made salt should have this title in their Christmas rotation. Patrick Stewart did take a turn in a Hollywood production of this classic tale in 1999, and that’s a plenty good adaptation.

But why settle for one of the great thespians and geek icons playing just a single role? Stewart also narrated an audiobook version of A Christmas Carol, and it is simply stellar. He gets to provide incredible voices for each character, plus he gets really into all the eerier parts of Charles Dickens’ holiday ghost story. Queue this up in your headphones on a snowy winter’s night, close your eyes, and you can really imagine that Captain Picard is personally reading you a bedtime story.

Discworld, Daleks, and Deep 13: A geeky holiday TV and movie watchlist Read More »