Tiny Vinyl is a new pocketable record format for the Spotify age

In 2019, Record Store Day partnered with manufacturer Crosley to revive a 3-inch collectible vinyl format first launched in Japan in 2004. Five years later, a new 4-inch-sized format called Tiny Vinyl wants to take the miniature vinyl collectible crown, and launch partner Target is throwing its considerable weight behind it as an exclusive launch partner, with 44 titles expected in the coming weeks.

It’s 2025, and the global vinyl record market has reached $2 billion in annual sales and is still growing at roughly 7 percent annually, according to market research firm Imarc. Vinyl record sales now account for over 50 percent of physical media sales for music (and this is despite a recent resurgence in both cassette and CD sales among Millennials). It’s in this landscape that Tiny Vinyl founders Neil Kohler and Jesse Mann decided to come up with a fun new collectible vinyl format.

An “aha” moment

Kohler’s day job is working with toy companies to develop and market their ideas. He was involved in helping Funko popularize its stylized vinyl figurines, now a ubiquitous presence at pop culture conventions, comic book stores, and toy shops of all kinds. Mann has worked in production, marketing, and the music business for nearly three decades, including a stint at LiveNation and years of running operations for the annual summer music festival Bonnaroo. Both men are based in Nashville—Music City, USA—and the proximity to one of the main centers of the music industry clearly had an impact.

In 2023, Kohler bumped into Drake Coker, CEO and general manager of Nashville Record Pressing, a newer vinyl manufacturing plant that opened in 2021.

“Would it be possible to make a real vinyl record that is small enough to fit inside the box with a Funko Pop, so roughly four inches in diameter?” Kohler asked Coker at the time.

Coker was convinced it was possible to do so. “It took quite a lot of energy to do the R&D and for Drake’s company to figure out how to do that in a technical sense,” Kohler explained to Ars. “It became evident very quickly that this was a really cool thing on its own, and it didn’t need to come in a Funko box,” Kohler told Ars. “As long as we made it authentic to what a standard 12-inch record would be, with sound, and art, and center labels, just miniaturized.”

That’s when Kohler contacted Mann to develop a strategy and make Tiny Vinyl its own unique collectible.

“The first prototype samples started coming out of production in May 2024, and we delivered the first Tiny Vinyl release to country musician Daniel Donato in July 2024,” Mann told Ars. “He took them out on tour, and the fan reaction gave us a sort of wind in the sails, that this would be something that fans would really love,” he said.

Of course, Record Store Day already has a small collectible vinyl format, and the Tiny Vinyl team became aware of it from the moment they started looking at the market.

“The Crosley 3-inch record player is both inspiring but also a different direction than what we wanted.” Kohler explained. “Crosley makes that as more of a promotional tool, to seed their record player business, and it’s this one-side piece that only plays on their miniature players,” Kohler said. “But here we’re focusing on something more, a two-sided piece that could play on any standard turntable.”

“Tiny Vinyl is a different concept. We’re basically trying, and having quite a bit of success, in creating a new vinyl format,” Coker said, “one that is more aligned with how artists are making and releasing music in the streaming era.”

How records are made

The basic process to press a vinyl record starts with cutting a lacquer master. A specially made disc of rather fragile lacquer is put on a cutting lathe—which looks sort of like an industrial turntable—and the audio signals are converted into mechanical movement in its cutting head. That movement is carved into fine grooves in the lacquer, creating the lacquer master.

The lacquer master is electroplated with a nickel alloy, creating a negative metal image of the grooves in the lacquer, called a “father.” This thin, relatively fragile metal negative is this electroplated again with a strong copper-based alloy, creating a new positive image called a “mother.” The mother is plated yet again, creating negative-image “stampers.” Once stampers are made for each side, they are mounted into a hydraulic press for stamping out records.

When a press is ready, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pellets are placed in a hopper and heated to around 250º F and typically extruded into a roughly 4-inch-diameter-thick disc called a “biscuit.” The biscuit is inserted into the press, with paper labels on each side, and the press uses anywhere from 100 to 150 tons of pressure to press a record. (Notably, heat and pressure adhere the labels to the record, not adhesive.)

Finally, the excess vinyl is trimmed off the edges (and often remelted and reused, especially in “eco” vinyl), and the finished records are stacked with metal plates to help cool off the hot vinyl and keep the records flat. All that has to be done while maintaining temperature and humidity to proper levels and keeping dust as far away from the stampers as possible.

To play a record, the turntable turns at a constant rotation speed, and a microscopic piece of diamond in the turntable’s stylus tracks the grooves and translates peaks and valleys into mechanical movement in the stylus. The stylus is connected to a cartridge, which converts the tiny mechanical movements into an electrical signal by moving tiny magnets within a coil. That signal is amplified twice—all turntables use a pre-amp to convert the audio signals to standard audio line-level, and then some other component (receiver, integrated amplifier, or something built-in to powered speakers) amplifies the signal to play back via speakers.

So the manufacturing process relies on the precision of multiple generations of mechanical copying before stamping out microscopic grooves into a relatively inexpensive material, and then, during playback, it depends on multiple steps of amplifying those microscopic grooves before you hear a single note of music. Every step along the way increases the chance that noise or other issues can affect what you hear.

Tiny Vinyl has some advantage here because Nashville Record Pressing is part of GZ Media. Before vinyl started its resurgence in 2007, many vinyl pressing plants closed, and the presses and other machinery were often discarded, with the metal being reused to make other machines. As vinyl manufacturing surged, there were few sources for the presses and other equipment to press records, and GZ’s size amplified those challenges.

“You know, GZ is based in the Czech Republic and is the oldest, largest manufacturer in the world,” Coker said. “And we’ve got very significant resources. I think what people don’t recognize is the depth and breadth of our technical resources. For instance, we’ve been making our own vinyl presses in the Czech Republic for over a decade now,” Coker told Ars. “So we can control every step of the process, from extruding PVC, pressing records, inserting them into sleeves, everything. We had to figure out how to do all that, but in miniature,” Coker said.

“There’s a lot of engineering, and there’s also kind of a lot of secret sauce in this,” Coker said. “So we’re a bit tight-lipped about how this is different. I’m very cryptic, but I will say that there are issues with PVC compound, there are issues with mastering, there are issues with plating, there are issues with pressing, there are issues with label application. It is definitely a challenge to make the sleeves and jackets at this size, get everything all assembled and get it wrapped, and get some stickers on it and have it look good. Some of those challenges are bigger than others, but we feel pretty good that we’ve had the time to really do the work that was necessary to figure this out.”

Challenges in manufacturing are also compounded by playback. As a turntable’s stylus moves closer to the center of a record, the linear speed decreases, which impacts playback quality. The angle of the stylus can also affect how well grooves are tracked, again impacting playback quality.

“So it’s a game about how to stay inside the manufacturing and playback infrastructure that exists,” Coker continued. “And to get something to work with a linear speed that’s never been tried before, right? And so what’s come out of that is a disc that we’re certainly very proud of,” he said.

Furthermore, 4-inch vinyl records are almost the exact size of the label on an LP or 7-inch single, so automatic turntables won’t work. If you want to play Tiny Vinyl at home, you’ll need a manual turntable or one that allows turning off auto stop and start. The good news is that the majority of turntables in use are manual. But some of the most popular entry-level models, such as Audio-Technica’s LP60-series, are strictly automatic.

That may change in the future. “We’re in touch with turntable manufacturers, and some have expressed an interest in making sure they are compatible with Tiny Vinyl,” Kohler told Ars. But that is likely contingent on the format selling in big numbers.

All aboard the Tiny Vinyl train

“We will make Tiny Vinyl for anyone, any artist or label that brings us music they have the rights to, and they can distribute that however they want,” Kohler told Ars. “Some people are using their own direct-to-consumer websites. Some other artists are doing it on tour, at merch tables. There is a Lindsay Sterling title that was the first Tiny Vinyl that was available at retail at Urban Outfitters.”

But for now, the big push is with the upcoming launch with Target, and so far, existing collectors are curious.

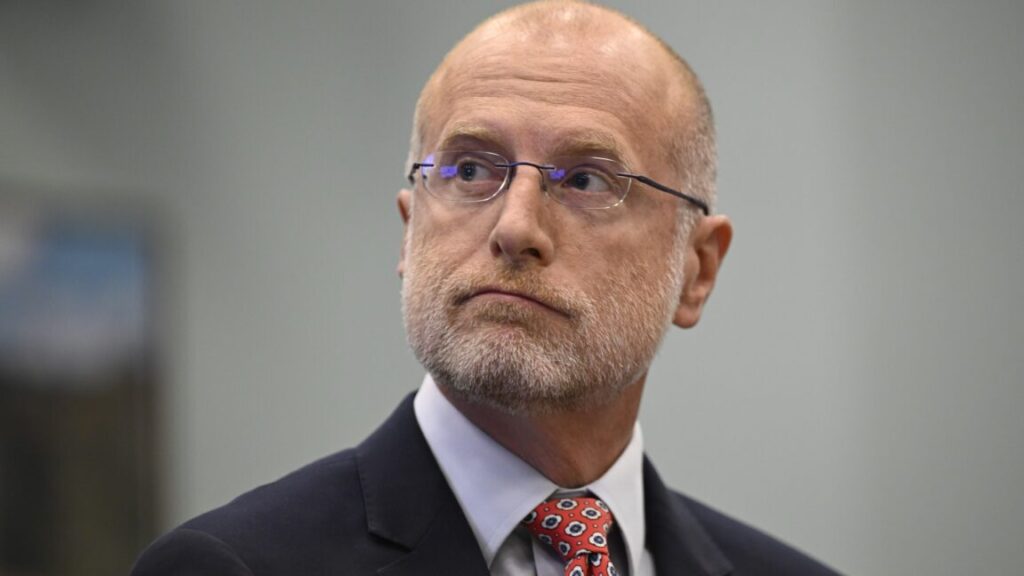

A sampling of the first batch of records. Credit: Chris Foresman

“I absolutely adore these 4-inch records,” Christina Stroven, an avid record collector from Arkansas, told Ars. “I think they’ll be super fun to collect and bring back all of the nostalgia of the cassette singles from the ’80s and ’90s,” she said, noting that she has over 1,500 records in her collection already.

“It is nice to have another format that still works on my turntable. I will for sure be picking up the Alessia Cara ‘Here’/’Scars To Your Beautiful’ single and The Rolling Stones and Kasey Musgraves, too.” Stroven said.

“I’ve already pre-ordered two Tiny Vinyl records,” Fred Whitacre Jr, a teacher, drummer, and record collector from Warren, Ohio, said. “But, I don’t think it’s something I’m going to delve very heavily into. I always like when vinyl pressings try something new, but for me, I’m probably going to stick with LPs and 45s.”

For Tiny Vinyl, this is really just the beginning. “This launch is being driven by Target,” Kohler noted. “It’s mostly because of my background in the toy industry. When I talked to the management team at Target, they said, ‘You know, let’s try and do something here, and we’ll help organize the labels.’”

Target already has relationships with major record labels, which have supplied the company with exclusive album variants in the past. “Really, the labels are supplying what Target is asking for, and we’re supplying the labels,” Kohler said.

And all this is to help establish Tiny Vinyl as a standard format. “We just wanted to get the ball rolling and make sure this is a success,” Kohler added. “We’ve been contacted by Barnes and Noble, and Walmart, and Best Buy, and other retailers. But Target jumped in with both feet.”

What does Crosley think about a new, potentially competing small vinyl format?

“I’m glad they’re doing it,” Scott Bingaman, owner of Crosley distributor Deer Park Distributors. “We’re still working on some great Record Store Day releases for 3-inch vinyl, but I’m rooting for these guys. I understand you have to pick a channel, and they went with the one that was most willing to step up. I hope distribution widens up because for me the definition of success is kids standing in line overnight at a record store, getting physical media.”

And will independent labels consider the format despite its relatively high price? That may depend on the audience.

Revelation Records, which specializes in hardcore and punk music, has a catalog that stretches back into the early days of straight edge and New York hardcore from the late ’80s. Founder Jordan Cooper thinks the format sounds interesting.

“This is still in the novelty realm, obviously, but seems like it could be a good merch item for bands to do,” he told Ars.

The vast majority of records sold are 12-inch LPs, but in the punk and indie scenes, a 7-inch EP is usually a cheaper way to get typically two to four songs to fans. A 4-inch single limits that to two relatively short songs, but again, the size and novelty factor could attract some buyers.

“I think as a fan, if I saw a band and song or two I liked on one of these, I might be motivated to pick it up,” Cooper said. “The price is really high for what you get, but at the same time, even 7-inches are pushing up over $10 now.”

Reminds one of a stack of CDs. Credit: Chris Foresman

With production capacity at full blast for the rollout with Target, though, Tiny Vinyl currently requires a minimum order of 2,000 units. That just isn’t financially feasible unless a band already has a large enough fan base to support it.

“Three-inch records are kind of a gimmick, and I feel the same about this format,” Carl Zenobi, owner of small, Pennsylvania-based indie label Powertone Records, told Ars. “I could see younger music fans seeing this at a merch table and thinking it’s cool, so that would be a plus if it draws younger fans into record collecting.”

“But from my reading, this is meant for bigger artists on major labels and not independent artists,” Zenobi said. Powertone has sold several short-run 3-inch lathe-cut releases in the past couple years, but quantities are typically in the dozens.

“For me and the artists I work with, we would be looking at 100 to maybe 300 units,” Zenobi explained. “For the amount of money that 2,000 units would likely cost, you might as well have a full LP pressed!”

Still, some artists have already had early success with the format. Alt-country-folk duo The Band Loula, who recently signed with Warner Nashville in 2024, has only released a handful of singles so far, primarily via streaming. But the group decided to try Tiny Vinyl for their songs “Running Off The Angels” and “Can’t Please ’Em All” earlier this year.

“We heard about Tiny Vinyl through our manager, and we thought it was a great idea since we’re still in more of a single release strategy,” Malachi Mills, one-half of The Band Loula, told Ars.

The band just got off a 34-show tour with country star Dierks Bentley that kicked off in May, and with nowhere near enough songs for an album, they decided to make a Tiny Vinyl to take on tour.

“We don’t have an album, but we have a few singles, so we said, ‘Let’s take our two favorite songs and put them on there,’” Mills said. We sell them for $15 at our merch booth, and for people that don’t have enough money to buy a shirt, they can still walk away with something really cool.”

“We’re a new band, the opening act, so I think people are still catching on to our merchandise,” Logan Simmons, The Band Loula’s other singer-songwriter half, explained. “People are definitely using the Tiny Vinyl to kind of capture a moment in time. Everybody wants us to sign them, and some fans told us they want to frame it, to frame the vinyl itself.”

“We watched our sales grow every night, and every date we played it felt like we were receiving more and more positive feedback,” Simmons said. “I think the Tiny Vinyl definitely had something to do with that.”

Overall, the band—and its fans—seem pleased with the results so far. “We’re also excited to see how they sell in different forums—we think they’ll sell even better in clubs and theaters,” Mills said. “As long as people keep buying them, we’ll keep making them. It sounds great, and seeing that tiny little thing on a full-size record player, you just think, ‘That’s really cool, man,’”

Here is where some of the differences in approach give Tiny Vinyl an advantage for record labels and bands to produce something to get into fans’ hands. Three-inch vinyl started as a kitschy toy for Japanese youth, and the format is only made by Toyokasei in Japan in partnership with Record Store Day. That means releases are limited to what can be pressed by Toyokasei and marketed by RSD.

Tiny Vinyl, on the other hand, has access to all of GZ Media’s pressing plants in Europe, the US, and Canada. So there is capacity to meet the demands of both independent and major labels.

But like The Band Loula discovered, Tiny Vinyl also aligns more with how artists are releasing music.

“A lot of data was supporting a surge in vinyl sales over the last 10 years,” Kohler explained. “So we really wanted to capture something that made vinyl a lot more digestible for the typical listener. I mean, I love vinyl. I grew up playing Dark Side of the Moon for like two weeks at a time, right? But few people are listening to a 12-inch vinyl from start to finish anymore. They’re listening to Spotify for 10 seconds and then they’re moving on.”

“So artists today, they don’t have to wait to accumulate, to write, produce, and master 10 or 12 songs to be able to start getting vinyl into the marketplace,” Coker said. “If they’ve got one or two, they’re good to go, and this format is much more closely aligned to the way most artists are releasing music into the marketplace, which gives vinyl a vibrancy and an immediacy and a relevance that sometimes is difficult to be able to keep together in a 12-inch format.”

Another consideration for artists is getting sales recognition, which is something all Tiny Vinyl releases will have, whereas many independent releases do not. “I think a really important piece is that Tiny Vinyl charts,” Mann said. “It is tracked through Luminate to make sure that it hits the Billboard charts.”

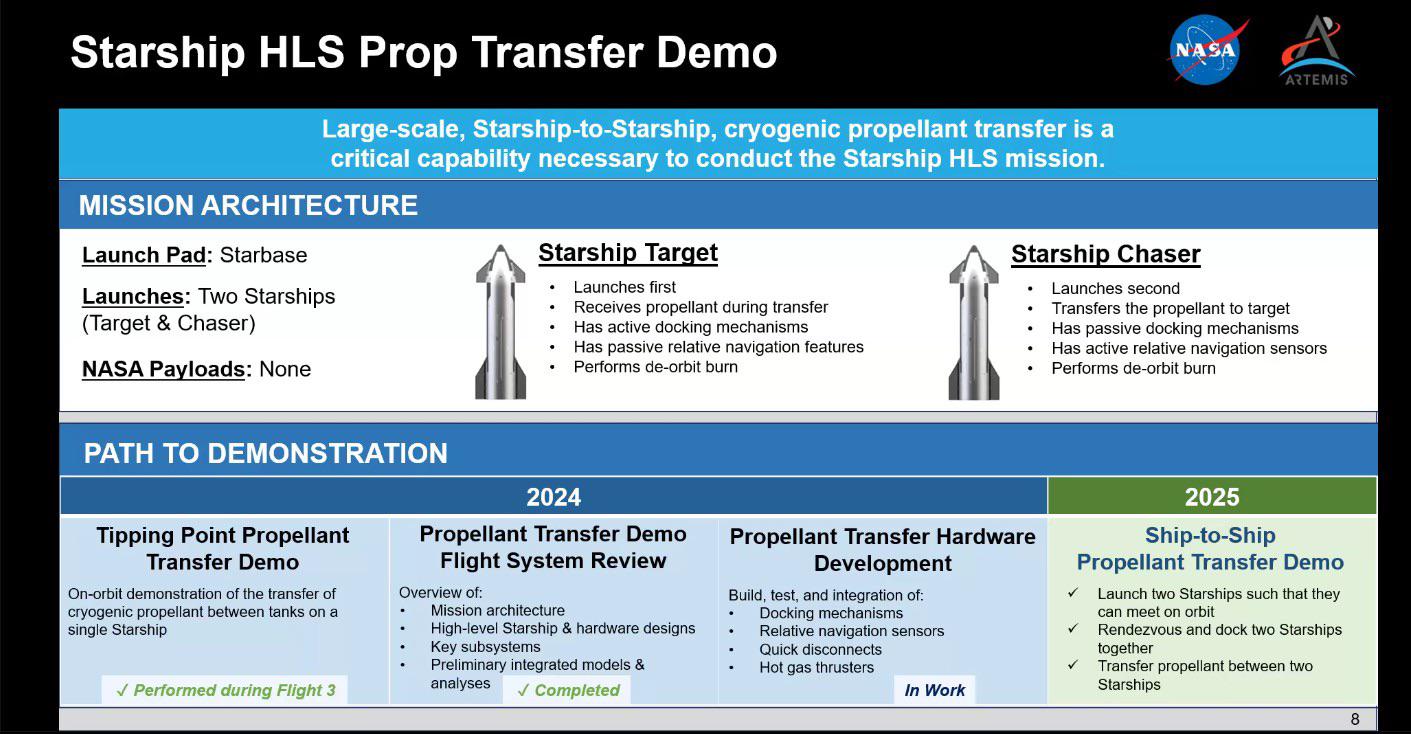

Vinyl Format Comparison

| 3” single | Tiny Vinyl single | 7” 45 rpm single | 12” 33 rpm LP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (jacket area) | 3.75×3.75in 95x95mm | 4.25×4.25in 108x108mm | 7.25×7.25in 184x184mm | 12.25×12.25in 314x314mm |

| Weight (with cover) | 0.80oz 22g | 1.35oz 37g | 2.00oz 56g | 10.60oz 300g |

| Sides | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Length (per side) | ~2.5 min | 4 min | 6 min | 23 min |

| Typical Cost | $12 | $15 | $10–15 | $25–35 |

Looking for adoption

Early signs are suggesting Tiny Vinyl has legs. “Rainbow Kitten Surprise, which is TV0002, they’re the first artist to release a second item with us,” Mann said. “Whereas we’ve had reorders for certain titles that sold really well, they’re the first artist that has had success in like a surprise-and-delight kind of way and then gone back to the well and were like, hey, we want to do this again.”

Though just over a dozen Tiny Vinyl records have been released in the wild so far, including titles from the likes of Derek and the Moonrocks, Melissa Etheridge, America’s Got Talent finalist Grace VanderWaal, and Blake Shelton, Target has over 40 titles lined up to start selling at the end of September. But interest has already grown beyond what’s already been announced.

Credit: Chris Foresman

“There are actually many in the process of manufacturing,” Kohler said. “TV0087 is in production, so while there are only a handful that are available for sale right now in the market, there’s a whole wave of new Tiny Vinyls coming.”

And Coker is convinced that independent labels and record stores will be more apt to embrace the format once it’s gotten some wings.

“In order to be able to give the format the broad adoption that we’ve been looking for, we had to assemble the ability to not only make these things but make them at scale, and then to get enough labels and enough artists attached to the project that we could launch a credible initial offering,” Coker said. “Tiny Vinyl, it’s still a baby, right? Giving it a chance to safely get launched into the world, where it can grow up and take whatever path that it takes is, I think, our job to try to be good parents, and help shepherd it through that process.”

Ultimately, fans will decide Tiny Vinyl’s fate. Whether it’s a resounding success or more of a collector niche like 3-inch vinyl remains to be seen. But Crosley’s Bingaman thinks even a little success is worth the effort.

“If it lasts one year or 10, it’s all about that kid walking into Target and getting that first piece of vinyl,” he said.

Tiny Vinyl is a new pocketable record format for the Spotify age Read More »