Browser extensions with 8 million users collect extended AI conversations

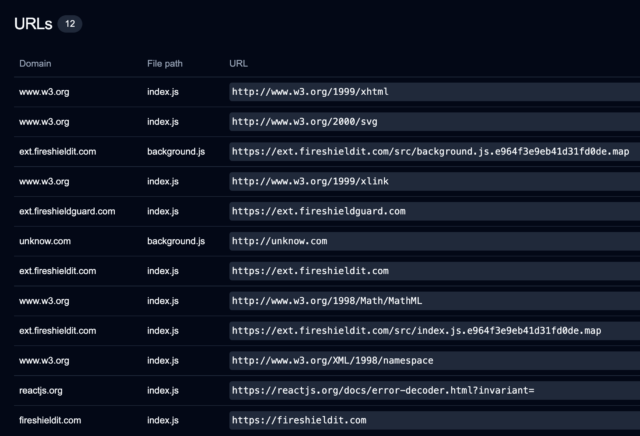

Besides ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, the extensions harvest all conversations from Copilot, Perplexity, DeepSeek, Grok, and Meta AI. Koi said the full description of the data captured includes:

- Every prompt a user sends to the AI

- Every response received

- Conversation identifiers and timestamps

- Session metadata

- The specific AI platform and model used

The executor script runs independently from the VPN networking, ad blocking, or other core functionality. That means that even when a user toggles off VPN networking, AI protection, ad blocking, or other functions, the conversation collection continues. The only way to stop the harvesting is to disable the extension in the browser settings or to uninstall it.

Koi said it first discovered the conversation harvesting in Urban VPN Proxy, a VPN routing extension that lists “AI protection” as one of its benefits. The data collection began in early July with the release of version 5.5.0.

“Anyone who used ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or the other targeted platforms while Urban VPN was installed after July 9, 2025 should assume those conversations are now on Urban VPN’s servers and have been shared with third parties,” the company said. “Medical questions, financial details, proprietary code, personal dilemmas—all of it, sold for ‘marketing analytics purposes.’”

Following that discovery, the security firm uncovered seven additional extensions with identical AI harvesting functionality. Four of the extensions are available in the Chrome Web Store. The other four are on the Edge add-ons page. Collectively, they have been installed more than 8 million times.

They are:

Chrome Store

- Urban VPN Proxy: 6 million users

- 1ClickVPN Proxy: 600,000 users

- Urban Browser Guard: 40,000 users

- Urban Ad Blocker: 10,000 users

Edge Add-ons:

- Urban VPN Proxy: 1,32 million users

- 1ClickVPN Proxy: 36,459 users

- Urban Browser Guard – 12,624 users

- Urban Ad Blocker – 6,476 users

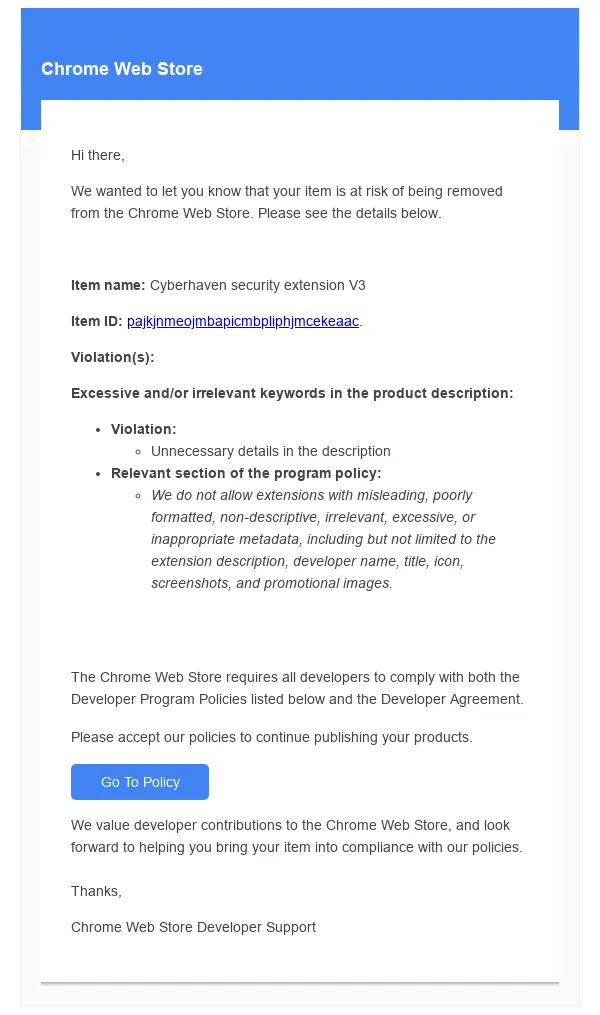

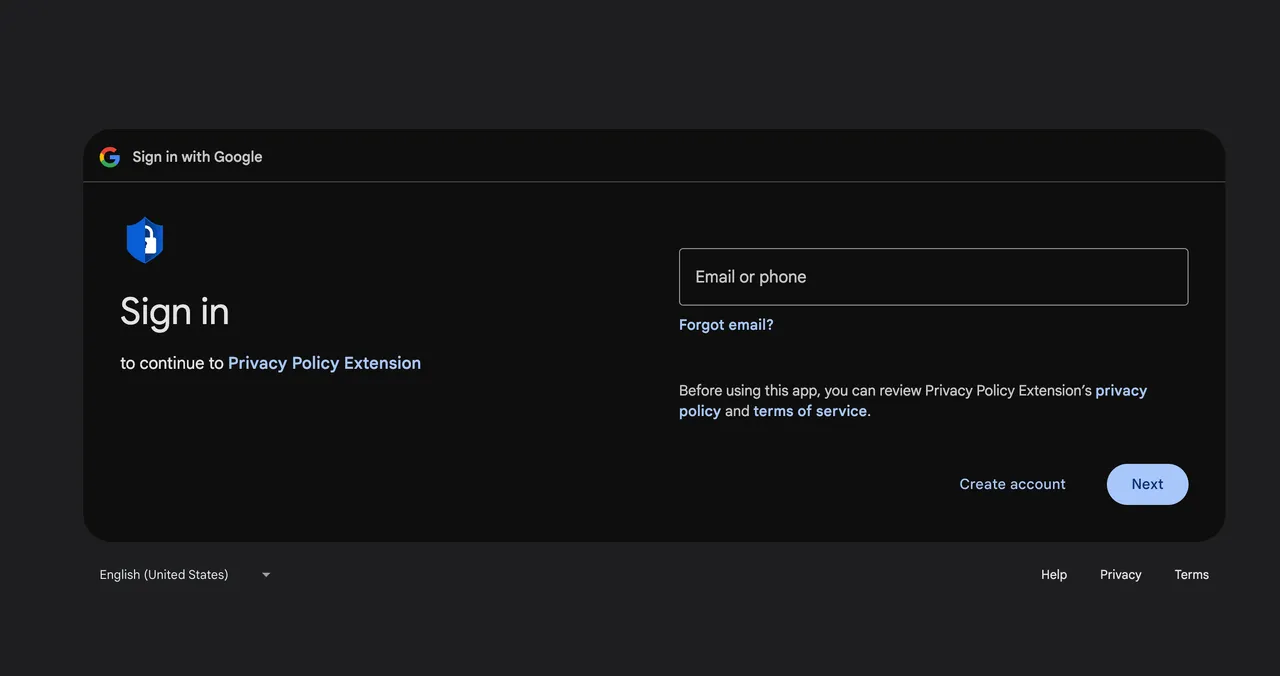

Read the fine print

The extensions come with conflicting messages about how they handle bot conversations, which often contain deeply personal information about users’ physical and mental health, finances, personal relationships, and other sensitive information that could be a gold mine for marketers and data brokers. The Urban VPN Proxy in the Chrome Web Store, for instance, lists “AI protection” as a benefit. It goes on to say:

Browser extensions with 8 million users collect extended AI conversations Read More »