The first crew launch of Boeing’s Starliner capsule is on hold indefinitely

Pursuing rationale —

“NASA will share more details once we have a clearer path forward.”

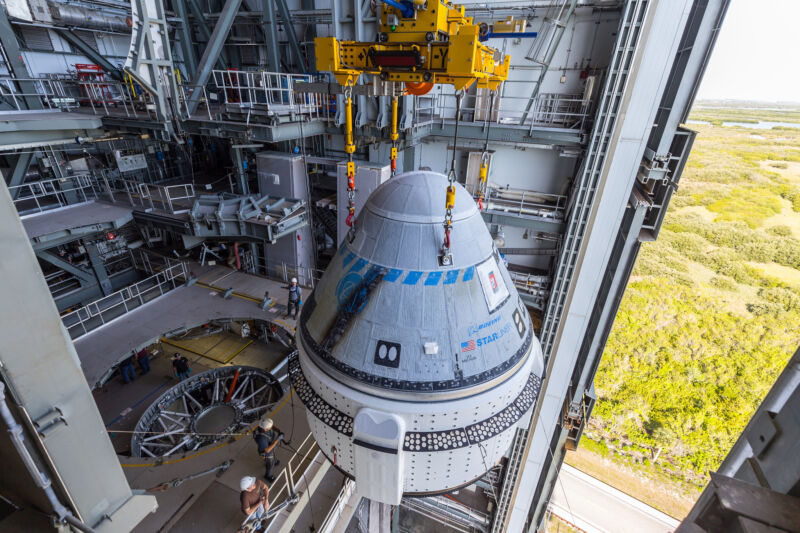

Enlarge / Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft on the eve of the first crew launch attempt earlier this month.

Miguel J. Rodriguez Carrillo/AFP via Getty Images

The first crewed test flight of Boeing’s long-delayed Starliner spacecraft won’t take off as planned Saturday and could face a longer postponement as engineers evaluate a stubborn leak of helium from the capsule’s propulsion system.

NASA announced the latest delay of the Starliner test flight late Tuesday. Officials will take more time to consider their options for how to proceed with the mission after discovering the small helium leak on the spacecraft’s service module.

The space agency did not describe what options are on the table, but sources said they range from flying the spacecraft “as is” with a thorough understanding of the leak and confidence it won’t become more significant in flight, to removing the capsule from its Atlas V rocket and taking it back to a hangar for repairs.

Theoretically, the former option could permit a launch attempt as soon as next week. The latter alternative could delay the launch until at least late summer.

“The team has been in meetings for two consecutive days, assessing flight rationale, system performance, and redundancy,” NASA said in a statement Tuesday night. “There is still forward work in these areas, and the next possible launch opportunity is still being discussed. NASA will share more details once we have a clearer path forward.”

Delays are nothing new for the Starliner program, but it’s not yet clear how this delay will compare to the spacecraft’s previous setbacks.

Software problems cut short an unpiloted test flight in 2019, forcing Boeing to fly a second demonstration mission. Starliner was on the launch pad when pre-flight checkouts revealed stuck valves in the spacecraft’s propulsion system in 2021. Boeing finally flew Starliner on a round-trip mission to the space station in May 2022. Concerns about Starliner’s parachutes and flammable tape inside the spacecraft’s crew cabin delayed the crewed test flight from last summer until this year.

Boeing aims to become the second company to fly astronauts to the space station under contract with NASA’s commercial crew program, following the start of SpaceX’s crew transportation service in 2020. Assuming a smooth crewed test flight, NASA hopes to clear the Starliner spacecraft for six-month crew rotation flights to the space station beginning next year.

In the doghouse

Engineers first noticed the helium leak during the first launch attempt for Starliner’s crewed test flight May 6, but managers did not consider it significant enough to stop the launch. Ultimately, a separate problem with a pressure regulation valve on the spacecraft’s United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket prompted officials to scrub the launch attempt.

NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams were already strapped into their seats inside the Starliner spacecraft on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, when officials ordered a halt to the May 6 countdown. Wilmore and Williams returned to their homes in Houston to await the next Starliner launch opportunity.

ULA returned the Atlas V rocket to its hangar, where technicians swapped out the faulty valve in time for another launch attempt May 17. NASA and Boeing pushed the launch date back to May 21, then to May 25, as engineers assessed the helium leak. The Atlas V rocket and Starliner spacecraft remain inside ULA’s Vertical Integration Facility to wait for the next launch opportunity.

Boeing engineers traced the leak to a flange on a single reaction control system thruster in one of four doghouse-shaped propulsion pods on the Starliner service module.

There are 28 reaction control system thrusters—essentially small rocket engines—on the Starliner service module. In orbit, these thrusters are used for minor course corrections and pointing the spacecraft in the proper direction. The service module has two sets of more powerful engines for larger orbital adjustments and launch-abort maneuvers.

The spacecraft’s propulsion system is pressurized using helium, an inert gas. The thrusters burn a mixture of toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants. Helium is not combustible, so a small leak is not likely to be a major safety issue on the ground. However, the system needs sufficient helium gas to force propellants from their internal storage tanks to Starliner’s thrusters.

In a statement last week, NASA described the helium leak as “stable” and said it would not pose a risk to the Starliner mission if it didn’t worsen. A Boeing spokesperson declined to provide Ars with any details about the helium leak rate.

If NASA and Boeing resolve their concerns about the helium leak without requiring lengthy repairs, the International Space Station could accommodate the docking of Starliner through part of July. After docking at the station, Wilmore and Williams will spend at least eight days at the complex before undocking to head for a parachute-assisted, airbag-cushioned landing in the Southwestern United States.

After July, the schedule gets messy.

The space station has a busy slate of multiple visiting crew and cargo vehicles in August, including the arrival of a fresh team of astronauts on a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft and the departure of an outgoing crew on another Dragon. There may be an additional window for Starliner to dock with the space station in late August or early September before the launch of SpaceX’s next cargo mission, which will occupy the docking port Starliner needs to use. The docking port opens up again in the fall.

ULA also has other high-priority missions it would like to launch from the same pad needed for the Starliner test flight. Later this summer, ULA plans to launch a US Space Force mission; it will be the last mission to use an Atlas V rocket. Then, ULA aims to launch the second demonstration flight of its new Vulcan Centaur rocket—the Atlas V’s replacement—as soon as September.

The first crew launch of Boeing’s Starliner capsule is on hold indefinitely Read More »