Ars Live recap: Is the AI bubble about to pop? Ed Zitron weighs in.

Despite connection hiccups, we covered OpenAI’s finances, nuclear power, and Sam Altman.

On Tuesday of last week, Ars Technica hosted a live conversation with Ed Zitron, host of the Better Offline podcast and one of tech’s most vocal AI critics, to discuss whether the generative AI industry is experiencing a bubble and when it might burst. My Internet connection had other plans, though, dropping out multiple times and forcing Ars Technica’s Lee Hutchinson to jump in as an excellent emergency backup host.

During the times my connection cooperated, Zitron and I covered OpenAI’s financial issues, lofty infrastructure promises, and why the AI hype machine keeps rolling despite some arguably shaky economics underneath. Lee’s probing questions about per-user costs revealed a potential flaw in AI subscription models: Companies can’t predict whether a user will cost them $2 or $10,000 per month.

You can watch a recording of the event on YouTube or in the window below.

Our discussion with Ed Zitron. Click here for transcript.

“A 50 billion-dollar industry pretending to be a trillion-dollar one”

I started by asking Zitron the most direct question I could: “Why are you so mad about AI?” His answer got right to the heart of his critique: the disconnect between AI’s actual capabilities and how it’s being sold. “Because everybody’s acting like it’s something it isn’t,” Zitron said. “They’re acting like it’s this panacea that will be the future of software growth, the future of hardware growth, the future of compute.”

In one of his newsletters, Zitron describes the generative AI market as “a 50 billion dollar revenue industry masquerading as a one trillion-dollar one.” He pointed to OpenAI’s financial burn rate (losing an estimated $9.7 billion in the first half of 2025 alone) as evidence that the economics don’t work, coupled with a heavy dose of pessimism about AI in general.

Donald Trump listens as Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang speaks at the White House during an event on “Investing in America” on April 30, 2025, in Washington, DC. Credit: Andrew Harnik / Staff | Getty Images News

“The models just do not have the efficacy,” Zitron said during our conversation. “AI agents is one of the most egregious lies the tech industry has ever told. Autonomous agents don’t exist.”

He contrasted the relatively small revenue generated by AI companies with the massive capital expenditures flowing into the sector. Even major cloud providers and chip makers are showing strain. Oracle reportedly lost $100 million in three months after installing Nvidia’s new Blackwell GPUs, which Zitron noted are “extremely power-hungry and expensive to run.”

Finding utility despite the hype

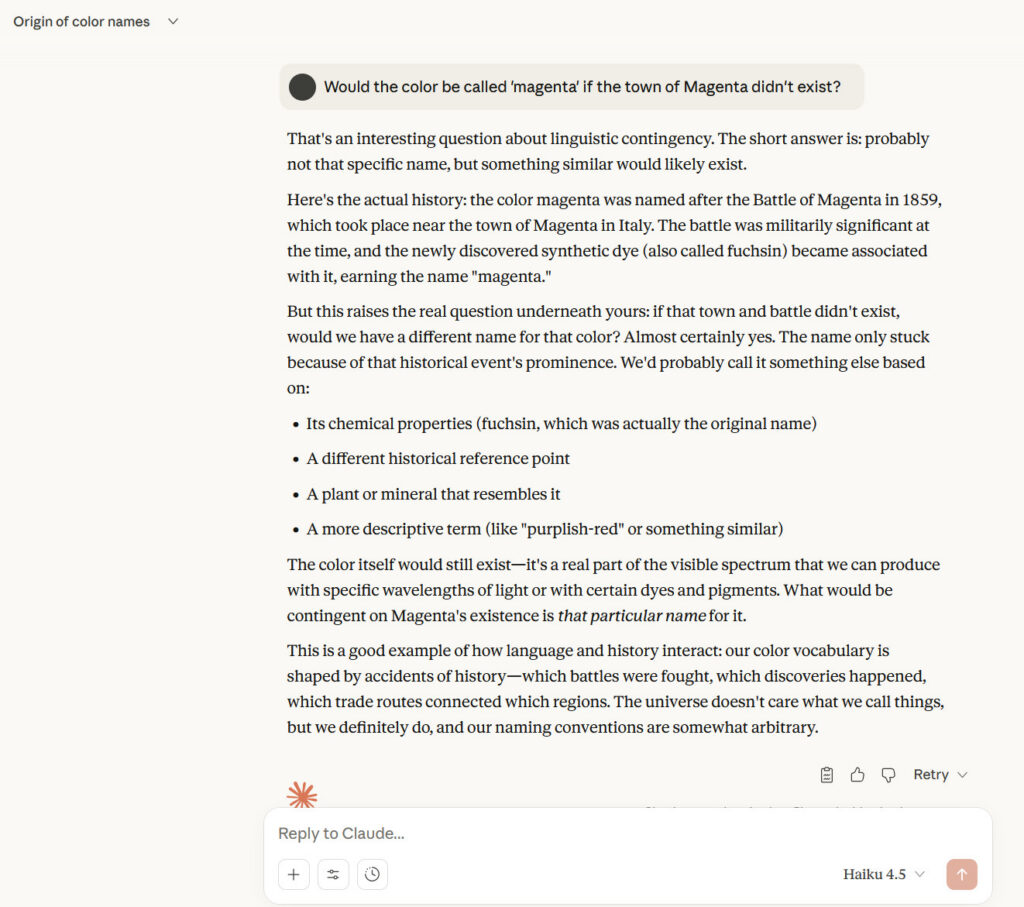

I pushed back against some of Zitron’s broader dismissals of AI by sharing my own experience. I use AI chatbots frequently for brainstorming useful ideas and helping me see them from different angles. “I find I use AI models as sort of knowledge translators and framework translators,” I explained.

After experiencing brain fog from repeated bouts of COVID over the years, I’ve also found tools like ChatGPT and Claude especially helpful for memory augmentation that pierces through brain fog: describing something in a roundabout, fuzzy way and quickly getting an answer I can then verify. Along these lines, I’ve previously written about how people in a UK study found AI assistants useful accessibility tools.

Zitron acknowledged this could be useful for me personally but declined to draw any larger conclusions from my one data point. “I understand how that might be helpful; that’s cool,” he said. “I’m glad that that helps you in that way; it’s not a trillion-dollar use case.”

He also shared his own attempts at using AI tools, including experimenting with Claude Code despite not being a coder himself.

“If I liked [AI] somehow, it would be actually a more interesting story because I’d be talking about something I liked that was also onerously expensive,” Zitron explained. “But it doesn’t even do that, and it’s actually one of my core frustrations, it’s like this massive over-promise thing. I’m an early adopter guy. I will buy early crap all the time. I bought an Apple Vision Pro, like, what more do you say there? I’m ready to accept issues, but AI is all issues, it’s all filler, no killer; it’s very strange.”

Zitron and I agree that current AI assistants are being marketed beyond their actual capabilities. As I often say, AI models are not people, and they are not good factual references. As such, they cannot replace human decision-making and cannot wholesale replace human intellectual labor (at the moment). Instead, I see AI models as augmentations of human capability: as tools rather than autonomous entities.

Computing costs: History versus reality

Even though Zitron and I found some common ground about AI hype, I expressed a belief that criticism over the cost and power requirements of operating AI models will eventually not become an issue.

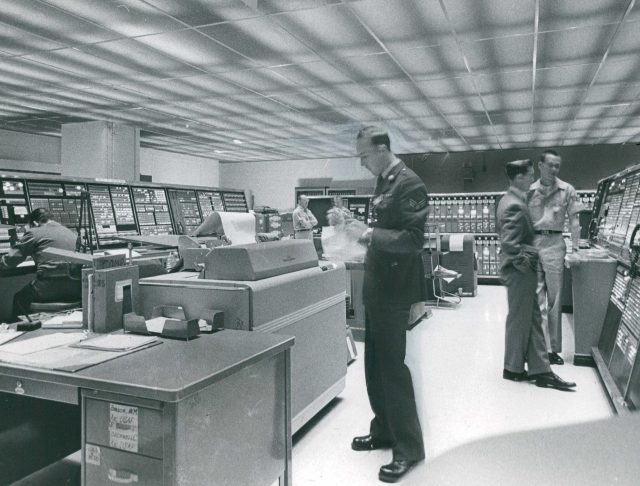

I attempted to make that case by noting that computing costs historically trend downward over time, referencing the Air Force’s SAGE computer system from the 1950s: a four-story building that performed 75,000 operations per second while consuming two megawatts of power. Today, pocket-sized phones deliver millions of times more computing power in a way that would be impossible, power consumption-wise, in the 1950s.

The blockhouse for the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment at Stewart Air Force Base, Newburgh, New York. Credit: Denver Post via Getty Images

“I think it will eventually work that way,” I said, suggesting that AI inference costs might follow similar patterns of improvement over years and that AI tools will eventually become commodity components of computer operating systems. Basically, even if AI models stay inefficient, AI models of a certain baseline usefulness and capability will still be cheaper to train and run in the future because the computing systems they run on will be faster, cheaper, and less power-hungry as well.

Zitron pushed back on this optimism, saying that AI costs are currently moving in the wrong direction. “The costs are going up, unilaterally across the board,” he said. Even newer systems like Cerebras and Grok can generate results faster but not cheaper. He also questioned whether integrating AI into operating systems would prove useful even if the technology became profitable, since AI models struggle with deterministic commands and consistent behavior.

The power problem and circular investments

One of Zitron’s most pointed criticisms during the discussion centered on OpenAI’s infrastructure promises. The company has pledged to build data centers requiring 10 gigawatts of power capacity (equivalent to 10 nuclear power plants, I once pointed out) for its Stargate project in Abilene, Texas. According to Zitron’s research, the town currently has only 350 megawatts of generating capacity and a 200-megawatt substation.

“A gigawatt of power is a lot, and it’s not like Red Alert 2,” Zitron said, referencing the real-time strategy game. “You don’t just build a power station and it happens. There are months of actual physics to make sure that it doesn’t kill everyone.”

He believes many announced data centers will never be completed, calling the infrastructure promises “castles on sand” that nobody in the financial press seems willing to question directly.

After another technical blackout on my end, I came back online and asked Zitron to define the scope of the AI bubble. He says it has evolved from one bubble (foundation models) into two or three, now including AI compute companies like CoreWeave and the market’s obsession with Nvidia.

Zitron highlighted what he sees as essentially circular investment schemes propping up the industry. He pointed to OpenAI’s $300 billion deal with Oracle and Nvidia’s relationship with CoreWeave as examples. “CoreWeave, they literally… They funded CoreWeave, became their biggest customer, then CoreWeave took that contract and those GPUs and used them as collateral to raise debt to buy more GPUs,” Zitron explained.

When will the bubble pop?

Zitron predicted the bubble would burst within the next year and a half, though he acknowledged it could happen sooner. He expects a cascade of events rather than a single dramatic collapse: An AI startup will run out of money, triggering panic among other startups and their venture capital backers, creating a fire-sale environment that makes future fundraising impossible.

“It’s not gonna be one Bear Stearns moment,” Zitron explained. “It’s gonna be a succession of events until the markets freak out.”

The crux of the problem, according to Zitron, is Nvidia. The chip maker’s stock represents 7 to 8 percent of the S&P 500’s value, and the broader market has become dependent on Nvidia’s continued hyper growth. When Nvidia posted “only” 55 percent year-over-year growth in January, the market wobbled.

“Nvidia’s growth is why the bubble is inflated,” Zitron said. “If their growth goes down, the bubble will burst.”

He also warned of broader consequences: “I think there’s a depression coming. I think once the markets work out that tech doesn’t grow forever, they’re gonna flush the toilet aggressively on Silicon Valley.” This connects to his larger thesis: that the tech industry has run out of genuine hyper-growth opportunities and is trying to manufacture one with AI.

“Is there anything that would falsify your premise of this bubble and crash happening?” I asked. “What if you’re wrong?”

“I’ve been answering ‘What if you’re wrong?’ for a year-and-a-half to two years, so I’m not bothered by that question, so the thing that would have to prove me right would’ve already needed to happen,” he said. Amid a longer exposition about Sam Altman, Zitron said, “The thing that would’ve had to happen with inference would’ve had to be… it would have to be hundredths of a cent per million tokens, they would have to be printing money, and then, it would have to be way more useful. It would have to have efficacy that it does not have, the hallucination problems… would have to be fixable, and on top of this, someone would have to fix agents.”

A positivity challenge

Near the end of our conversation, I wondered if I could flip the script, so to speak, and see if he could say something positive or optimistic, although I chose the most challenging subject possible for him. “What’s the best thing about Sam Altman,” I asked. “Can you say anything nice about him at all?”

“I understand why you’re asking this,” Zitron started, “but I wanna be clear: Sam Altman is going to be the reason the markets take a crap. Sam Altman has lied to everyone. Sam Altman has been lying forever.” He continued, “Like the Pied Piper, he’s led the markets into an abyss, and yes, people should have known better, but I hope at the end of this, Sam Altman is seen for what he is, which is a con artist and a very successful one.”

Then he added, “You know what? I’ll say something nice about him, he’s really good at making people say, ‘Yes.’”

Ars Live recap: Is the AI bubble about to pop? Ed Zitron weighs in. Read More »