New Geekbench AI benchmark can test the performance of CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs

hit the bench —

Performance test comes out of beta as NPUs become standard equipment in PCs.

Primate Labs

Neural processing units (NPUs) are becoming commonplace in chips from Intel and AMD after several years of being something you’d find mostly in smartphones and tablets (and Macs). But as more companies push to do more generative AI processing, image editing, and chatbot-ing locally on-device instead of in the cloud, being able to measure NPU performance will become more important to people making purchasing decisions.

Enter Primate Labs, developers of Geekbench. The main Geekbench app is designed to test CPU performance as well as GPU compute performance, but for the last few years, the company has been experimenting with a side project called Geekbench ML (for “Machine Learning”) to test the inference performance of NPUs. Now, as Microsoft’s Copilot+ initiative gets off the ground and Intel, AMD, Qualcomm, and Apple all push to boost NPU performance, Primate Labs is bumping Geekbench ML to version 1.0 and renaming it “Geekbench AI,” a change that will presumably help it ride the wave of AI-related buzz.

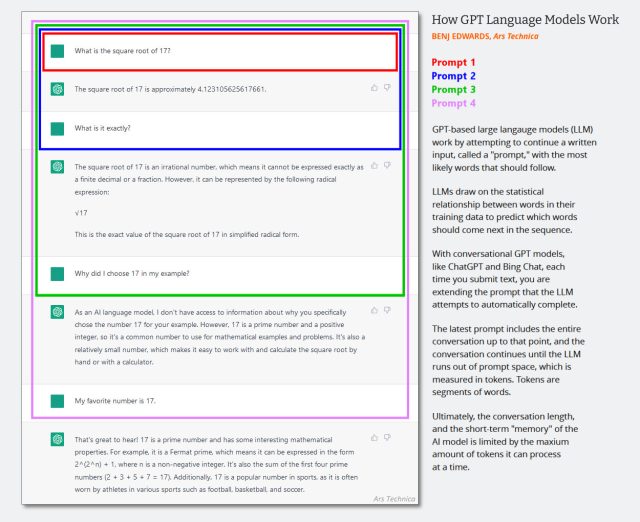

“Just as CPU-bound workloads vary in how they can take advantage of multiple cores or threads for performance scaling (necessitating both single-core and multi-core metrics in most related benchmarks), AI workloads cover a range of precision levels, depending on the task needed and the hardware available,” wrote Primate Labs’ John Poole in a blog post about the update. “Geekbench AI presents its summary for a range of workload tests accomplished with single-precision data, half-precision data, and quantized data, covering a variety used by developers in terms of both precision and purpose in AI systems.”

In addition to measuring speed, Geekbench AI also attempts to measure accuracy, which is important for machine-learning workloads that rely on producing consistent outcomes (identifying and cataloging people and objects in a photo library, for example).

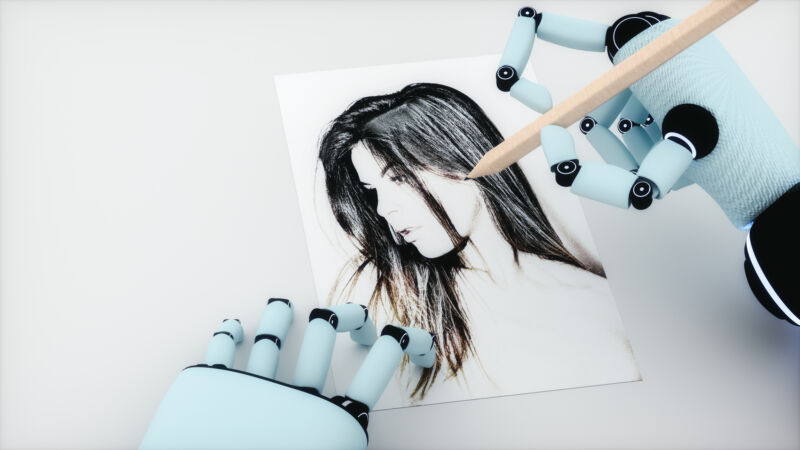

Enlarge / Geekbench AI can run AI workloads on your CPU, GPU, or NPU (when you have a system with an NPU that’s compatible).

Andrew Cunningham

Geekbench AI supports several AI frameworks: OpenVINO for Windows and Linux, ONNX for Windows, Qualcomm’s QNN on Snapdragon-powered Arm PCs, Apple’s CoreML on macOS and iOS, and a number of vendor-specific frameworks on various Android devices. The app can run these workloads on the CPU, GPU, or NPU, at least when your device has a compatible NPU installed.

On Windows PCs, where NPU support and APIs like Microsoft’s DirectML are still works in progress, Geekbench AI supports Intel and Qualcomm’s NPUs but not AMD’s (yet).

“We’re hoping to add AMD NPU support in a future version once we have more clarity on how best to enable them from AMD,” Poole told Ars.

Geekbench AI is available for Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS/iPadOS, and Android. It’s free to use, though a Pro license gets you command-line tools, the ability to run the benchmark without uploading results to the Geekbench Browser, and a few other benefits. Though the app is hitting 1.0 today, the Primate Labs team expects to update the app frequently for new hardware, frameworks, and workloads as necessary.

“AI is nothing if not fast-changing,” Poole continued in the announcement post, “so anticipate new releases and updates as needs and AI features in the market change.”

New Geekbench AI benchmark can test the performance of CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs Read More »